Radius (bone)

The radius or radial bone (PL: radii or radiuses) is one of the two large bones of the forearm, the other being the ulna. It extends from the lateral side of the elbow to the thumb side of the wrist and runs parallel to the ulna. The ulna is longer than the radius, but the radius is thicker. The radius is a long bone, prism-shaped and slightly curved longitudinally.

| Radius | |

|---|---|

The radius (shown in red) is a bone in the forearm. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | radius |

| MeSH | D011884 |

| TA98 | A02.4.05.001 |

| TA2 | 1210 |

| FMA | 23463 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

The radius is part of two joints: the elbow and the wrist. At the elbow, it joins with the capitulum of the humerus, and in a separate region, with the ulna at the radial notch. At the wrist, the radius forms a joint with the ulna bone.

Structure

The long narrow medullary cavity is enclosed in a strong wall of compact bone. It is thickest along the interosseous border and thinnest at the extremities, same over the cup-shaped articular surface (fovea) of the head.

The trabeculae of the spongy tissue are somewhat arched at the upper end and pass upward from the compact layer of the shaft to the fovea capituli (the humerus's cup-shaped articulatory notch); they are crossed by others parallel to the surface of the fovea. The arrangement at the lower end is somewhat similar. It is missing in radial aplasia.

The radius has a body and two extremities. The upper extremity of the radius consists of a somewhat cylindrical head articulating with the ulna and the humerus, a neck, and a radial tuberosity. The body of the radius is self-explanatory, and the lower extremity of the radius is roughly quadrilateral in shape, with articular surfaces for the ulna, scaphoid and lunate bones. The distal end of the radius forms two palpable points, radially the styloid process and Lister's tubercle on the ulnar side. Along with the proximal and distal radioulnar articulations, an interosseous membrane originates medially along the length of the body of the radius to attach the radius to the ulna.[1]

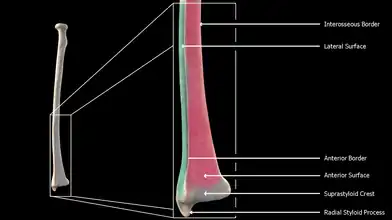

Near the wrist

The distal end of the radius is large and of quadrilateral form.

- Joint surfaces

It is provided with two articular surfaces – one below, for the carpus, and another at the medial side, for the ulna.

- The carpal articular surface is triangular, concave, smooth, and divided by a slight antero-posterior ridge into two parts. Of these, the lateral, triangular, articulates with the scaphoid bone; the medial, quadrilateral, with the lunate bone.

- The articular surface for the ulna is called the ulnar notch (sigmoid cavity) of the radius; it is narrow, concave, smooth, and articulates with the head of the ulna.

These two articular surfaces are separated by a prominent ridge, to which the base of the triangular articular disk is attached; this disk separates the wrist-joint from the distal radioulnar articulation.

- Other surfaces

This end of the bone has three non-articular surfaces – volar, dorsal, and lateral.

- The volar surface, rough and irregular, affords attachment to the volar radiocarpal ligament.

- The dorsal surface is convex, affords attachment to the dorsal radiocarpal ligament, and is marked by three grooves. Enumerated from the lateral side:

- The first groove is broad, but shallow, and subdivided into two by a slight ridge: the lateral of these two, transmits the tendon of the extensor carpi radialis longus muscle; the medial, the tendon of the extensor carpi radialis brevis muscle.

- The second is deep but narrow, and bounded laterally by a sharply defined ridge; it is directed obliquely from above downward and lateralward, and transmits the tendon of the extensor pollicis longus muscle.

- The third is broad, for the passage of the tendons of the extensor indicis proprius and extensor digitorum communis.

- The lateral surface is prolonged obliquely downward into a strong, conical projection, the styloid process, which gives attachment by its base to the tendon of the brachioradialis, and by its apex to the radial collateral ligament of wrist joint. The lateral surface of this process is marked by a flat groove, for the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus muscle and extensor pollicis brevis muscle.

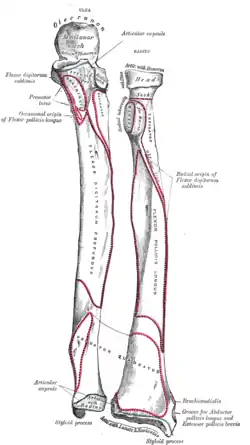

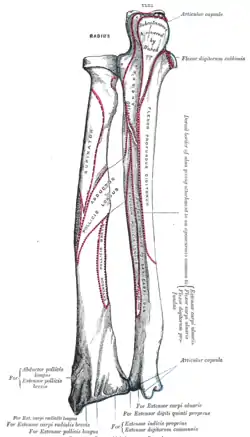

Body

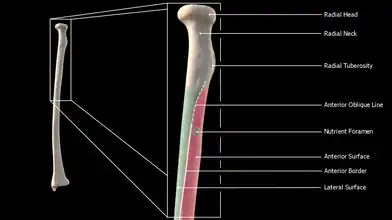

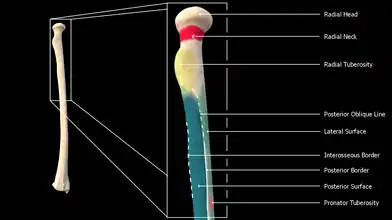

The body of the radius (or shaft of radius) is prismoid in form, narrower above than below, and slightly curved, so as to be convex lateralward. It presents three borders and three surfaces.

- Borders

The volar border (margo volaris; anterior border; palmar;) extends from the lower part of the tuberosity above to the anterior part of the base of the styloid process below, and separates the volar from the lateral surface. Its upper third is prominent, and from its oblique direction has received the name of the oblique line of the radius; it gives origin to the flexor digitorum superficialis muscle (also flexor digitorum sublimis) and flexor pollicis longus muscle; the surface above the line gives insertion to part of the supinator muscle. The middle third of the volar border is indistinct and rounded. The lower fourth is prominent, and gives insertion to the pronator quadratus muscle, and attachment to the dorsal carpal ligament; it ends in a small tubercle, into which the tendon of the brachioradialis muscle is inserted.

The dorsal border (margo dorsalis; posterior border) begins above at the back of the neck, and ends below at the posterior part of the base of the styloid process; it separates the posterior from the lateral surface. is indistinct above and below, but well-marked in the middle third of the bone.

The interosseous border (internal border; crista interossea; interosseous crest;) begins above, at the back part of the tuberosity, and its upper part is rounded and indistinct; it becomes sharp and prominent as it descends, and at its lower part divides into two ridges which are continued to the anterior and posterior margins of the ulnar notch. To the posterior of the two ridges the lower part of the interosseous membrane is attached, while the triangular surface between the ridges gives insertion to part of the pronator quadratus muscle. This crest separates the volar from the dorsal surface, and gives attachment to the interosseous membrane. The connection between the two bones is actually a joint referred to as a syndesmosis joint.

- Surfaces

The volar surface (facies volaris; anterior surface) is concave in its upper three-fourths, and gives origin to the flexor pollicis longus muscle; it is broad and flat in its lower fourth, and affords insertion to the Pronator quadratus. A prominent ridge limits the insertion of the Pronator quadratus below, and between this and the inferior border is a triangular rough surface for the attachment of the volar radiocarpal ligament. At the junction of the upper and middle thirds of the volar surface is the nutrient foramen, which is directed obliquely upward.

The dorsal surface (facies dorsalis; posterior surface) is convex, and smooth in the upper third of its extent, and covered by the Supinator. Its middle third is broad, slightly concave, and gives origin to the Abductor pollicis longus above, and the extensor pollicis brevis muscle below. Its lower third is broad, convex, and covered by the tendons of the muscles which subsequently run in the grooves on the lower end of the bone.

The lateral surface (facies lateralis; external surface) is convex throughout its entire extent and is known as the convexity of the radius, curving outwards to be convex at the side. Its upper third gives insertion to the supinator muscle. About its center is a rough ridge, for the insertion of the pronator teres muscle.[2] Its lower part is narrow, and covered by the tendons of the abductor pollicis longus muscle and extensor pollicis brevis muscle.

Near the elbow

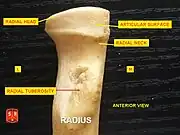

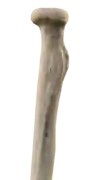

The upper extremity of the radius (or proximal extremity) presents a head, neck, and tuberosity.

- The radial head has a cylindrical form, and on its upper surface is a shallow cup or fovea for articulation with the capitulum (or capitellum) of the humerus. The circumference of the head is smooth; it is broad medially where it articulates with the radial notch of the ulna, narrow in the rest of its extent, which is embraced by the annular ligament. The deepest point in the fovea is not axi-symmetric with the long axis of the radius, creating a cam effect during pronation and supination.

- The head is supported on a round, smooth, and constricted portion called the neck, on the back of which is a slight ridge for the insertion of part of the supinator muscle.

- Beneath the neck, on the medial side, is an eminence, the radial tuberosity; its surface is divided into a posterior, rough portion, for the insertion of the tendon of the biceps brachii muscle, and an anterior, smooth portion, on which a bursa is interposed between the tendon and the bone.

Development

The radius is ossified from three centers: one for the body, and one for each extremity. That for the body makes its appearance near the center of the bone, during the eighth week of fetal life.

Ossification commences in the lower end between 9 and 26 months of age. The ossification center for the upper end appears by the fifth year.

The upper epiphysis fuses with the body at the age of seventeen or eighteen years, the lower about the age of twenty.

An additional center sometimes found in the radial tuberosity, appears about the fourteenth or fifteenth year.

Function

Muscle attachments

The biceps muscle inserts on the radial tuberosity of the upper extremity of the bone. The upper third of the body of the bone attaches to the supinator, the flexor digitorum superficialis, and the flexor pollicis longus muscles. The middle third of the body attaches to the extensor ossis metacarpi pollicis, extensor primi internodii pollicis, and the pronator teres muscles. The lower quarter of the body attaches to the pronator quadratus muscle and the tendon of the supinator longus.

Clinical significance

Radial aplasia refers to the congenital absence or shortness of the radius.

Fracture

Specific fracture types of the radius include:

- Proximal radius fracture. A fracture within the capsule of the elbow joint results in the fat pad sign or "sail sign" which is a displacement of the fat pad at the elbow.

- Essex-Lopresti fracture – a fracture of the radial head with concomitant dislocation of the distal radio-ulnar joint with disruption of the interosseous membrane.[3]

- Radial shaft fracture

- Distal radius fracture

- Galeazzi fracture – a fracture of the radius with dislocation of the distal radioulnar joint

- Colles' fracture – a distal fracture of the radius with dorsal (posterior) displacement of the wrist and hand

- Smith's fracture – a distal fracture of the radius with volar (ventral) displacement of the wrist and hand

- Barton's fracture – an intra-articular fracture of the distal radius with dislocation of the radiocarpal joint.

History

The word radius is Latin for "ray". In the context of the radius bone, a ray can be thought of rotating around an axis line extending diagonally from center of capitulum to the center of distal ulna. While the ulna is the major contributor to the elbow joint, the radius primarily contributes to the wrist joint.[4]

The radius is named so because the radius (bone) acts like the radius (of a circle). It rotates around the ulna and the far end (where it joins to the bones of the hand), known as the styloid process of the radius, is the distance from the ulna (center of the circle) to the edge of the radius (the circle). The ulna acts as the center point to the circle because when the arm is rotated the ulna does not move.

Animals

In four-legged animals, the radius is the main load-bearing bone of the lower forelimb. Its structure is similar in most terrestrial tetrapods, but it may be fused with the ulna in some mammals (such as horses) and reduced or modified in animals with flippers or vestigial forelimbs.[5]

Gallery

Radius Bone and Radius of a circle comparison.

Radius Bone and Radius of a circle comparison. Position of radius (shown in red).

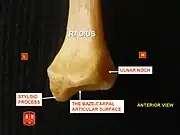

Position of radius (shown in red). Radius, styloid process - anterior view

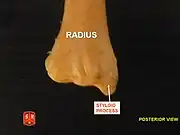

Radius, styloid process - anterior view Radius, ulnar notch - posterior view

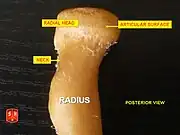

Radius, ulnar notch - posterior view Radius, radial head – posterior view

Radius, radial head – posterior view Radius, radial head – anterior view

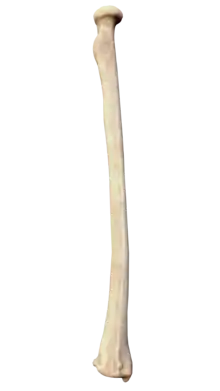

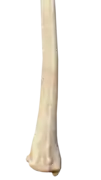

Radius, radial head – anterior view Radius l. dx. – ant. view

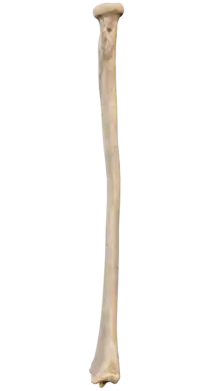

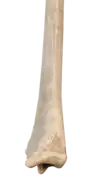

Radius l. dx. – ant. view Radius l. dx. – post. view

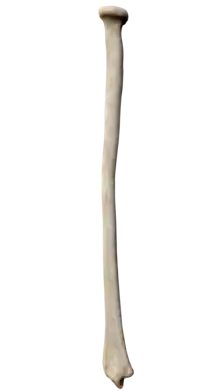

Radius l. dx. – post. view Anterior surface of radius (at right)

Anterior surface of radius (at right) Posterior surface of radius (at left)

Posterior surface of radius (at left) Posterior View of Right Proximal Radius

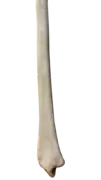

Posterior View of Right Proximal Radius Posterior View of Right Distal Radius

Posterior View of Right Distal Radius Medial View of Right Proximal Radius

Medial View of Right Proximal Radius Medial View of Right Distal Radius

Medial View of Right Distal Radius Lateral View of Right Distal Radius

Lateral View of Right Distal Radius Anterior View of Right Distal Radius

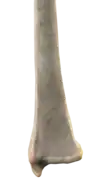

Anterior View of Right Distal Radius Anterior View of Right Proximal Radius

Anterior View of Right Proximal Radius- Radius Bone Anatomy

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 219 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 219 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Clemente, Carmine D. (2007), Anatomy: A Regional Atlas of the Human Body (5th ed.), Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

- Moore, Keith; Anne Agur (2007). Essential Clinical Anatomy Third Edition. USA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 446. ISBN 978-0-7817-6274-8.

- Essex Lopresti fracture at Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics online

- Marieb, E., R.N., Ph.D; Mallatt, J., Ph.D. & Wilhelm, P., Ph.D. (2008), Human Anatomy (5th ed.), San Francisco, CA: Pearson Benjamin Cummings, p. 188

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. p. 199. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.