Bolesław I the Tall

Bolesław I the Tall (Polish: Bolesław I Wysoki; 1127 – 7 or 8 December 1201) was Duke of Wroclaw from 1163 until his death in 1201.

Bolesław I the Tall | |

|---|---|

| Duke of Wroclaw | |

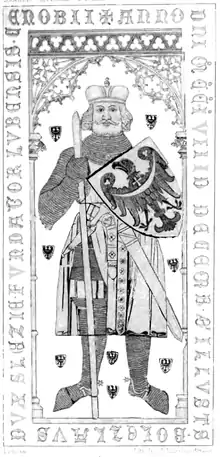

Bolesław's tomb in Lubiąż | |

| Born | 1127 |

| Died | 7 or 8 December 1201 Leśnica (now part of City of Wrocław) |

| Buried | Cistercian monastery in Lubiąż |

| Noble family | Silesian Piasts |

| Spouse(s) | Zvenislava of Kiev Christina |

| Issue | Jarosław, Duke of Opole Henry the Bearded Adelaida Zbyslava |

| Father | Władysław II the Exile |

| Mother | Agnes of Babenberg |

Early years

He was the eldest son of Władysław II the Exile by his wife Agnes of Babenberg, daughter of Margrave Leopold III of Austria and half-sister of King Conrad III of Germany. Bolesław spent his childhood in the court of his grandfather and namesake, Bolesław III Wrymouth, in Płock. It was not until 1138, after the death of Bolesław III, that he moved with his parents to Kraków, which became the capital of the Seniorate Province, ruled by his father as high duke and overlord of Poland.

The reign of Władysław II was short and extremely stormy. The conflicts began when the high duke tried to remove his half-brothers, the junior dukes, from their districts. According to the chronicler Wincenty Kadłubek, the confrontation between the siblings was mainly instigated by Władysław II's wife, Agnes of Babenberg, who believed that her husband, as the eldest son, was the rightful sole ruler of the whole country. On the other hand, Salomea of Berg, widow of Bolesław III and Władysław II's stepmother, attempted to form alliances with foreign rulers and took every opportunity to secure the reign of her sons, the junior dukes. She feared that they would be relegated from their positions to make way for Władysław II's sons, the young Bolesław and his brothers Mieszko Tanglefoot and Konrad.

The conflict erupted in 1141, when Salomea of Berg, without the knowledge of the high duke, decided to leave the land of Łęczyca, her dower, to her sons and tried to give her youngest daughter, Agnes, in marriage to one of the sons of Grand Prince Vsevolod II Olgovich of Kiev. Władysław II was faster, however, and he gave Grand Prince Vsevolod II several additional political advantages, including a marriage between Bolesław and Vsevolod II's daughter, Zvenislava, which took place in 1142.

Trip to Ruthenia

The Polish-Ruthenian alliance soon proved to be extremely important in the struggle between Władysław II and the Junior Dukes. The final conflicts took place after the death of Salomea of Berg in 1144. It seemed that a victory for the High Duke - thanks to his military predominance - was just a matter of time. In fact, Władysław II was so confident of winning at home that he sent Bolesław to aid Grand Prince Vsevolod II during a revolt in Kiev.

Unfortunately, Bolesław's expedition ended in complete disaster, as the Grand Prince's death from disease created general confusion in Kiev. Then in 1146, Bolesław had to return quickly to Poland to help his father. The few troops which he recruited were not enough to stop the general rebellion against Władysław II, who was completely defeated by the Junior Dukes. The deposed High Duke and his family initially escaped to the Prague court of Duke Vladislav II of Bohemia.

Attempt at restoration

After a short time in Bohemia, Władysław II and his family moved to Germany, where his brother-in-law, King Conrad III, offered his hospitality and assistance toward the high duke's restoration. At first, it seemed that the exile would just be for a few months, thanks to the family connections of Duchess Agnes; however, their hurried and insufficiently prepared expedition failed to cross the Oder River, and ultimately failed because of strong opposition from Władysław II's former subjects and problems Conrad III had within Germany as a result of his extended travels. The king gave Władysław II and his family the town of Altenburg in Saxony. This was intended as a temporary residence, but Władysław II would spend the rest of his life there.

Tired of a tedious life in Altenburg, Bolesław traveled to the court of his protector, King Conrad III. With him, the young Polish prince extensively took part in German political affairs. In 1148 he joined in the Second Crusade with Conrad III, during which he visited Constantinople and the Holy Land. Conrad III died in 1152 without having secured the return of Władysław II to Poland. His successor was his energetic nephew Frederick Barbarossa, whose service Bolesław almost immediately joined. The first action of the new German ruler, however, was not to help Władysław II, but instead to march against Rome and be crowned emperor. Bolesław accompanied him.

Expedition of Frederick Barbarossa to Poland

It was not until 1157 that the emperor finally organized an expedition against Poland. It is unknown whether Bolesław, his brothers, or his father directly participated in the expedition. However, despite the military victory and the humiliating submission of High Duke Bolesław IV the Curly to Frederick Barbarossa, the emperor decided to maintain the rule of Bolesław IV and the junior dukes in Poland, and not to restore Władysław II to the throne. Two years later, on 30 May 1159, the disappointed former high duke died in his exile in Altenburg.

Restoration of the Silesian inheritance

Despite his dissatisfaction at the emperor's treatment of his father, Bolesław remained at the side of the emperor, participating in his many wars. From 1158 to 1162 he took part in the Barbarossa's expedition to Italy, where he won fame after killing a well-known Italian knight in a duel on the walls of Milan.

Bolesław's faithful service to the emperor was finally rewarded in 1163, when Barbarossa succeeded through diplomacy in restoring to the descendants of Władysław II their inheritance over Silesia. By an agreement signed in Nuremberg, Germany, Bolesław IV agreed to accept the return of the exiled princes. He did so because, after the death of Władysław II, his sons could not directly challenge his authority as the senior duke, and they had not yet established any support within Poland. In addition, seating them would satisfy Barbarossa and thus keep him away from Poland.[1] However Bolesław IV decided to maintain the security of his lands and retain the control over the main Silesian cities of Wroclaw, Opole, Racibórz, Głogów, and Legnica.

After almost 16 years of exile, Bolesław returned to Silesia with his second wife, Christina (Zvenislava had died around 1155); his elder children, Jarosław and Olga; and his younger brother Mieszko Tanglefoot. The youngest brother, Konrad, remained in Germany.

Bolesław and Mieszko initially ruled jointly and two years later (1165) both retook the major Silesian cities handed back by the high duke and obtained full control over all Silesia. However Bolesław, as the eldest brother, held overall authority. Three years after taking control over Silesia, Bolesław felt strong enough to lead a retaliatory expedition against High Duke Bolesław IV to try and recover supremacy over Poland.

Rebellion of Mieszko Tanglefoot

Bolesław's exercise of overall power at the expense of his younger brother caused a revolt by Mieszko Tanglefoot in 1172. In a major disturbance in the Silesian ducal family, Mieszko supported Jarosław, the eldest son of Bolesław, who was resentful against his father because had been forced to become a priest due to the intrigues of his stepmother Christina, who wished for her sons to be the only heirs. The rebellion was a complete surprise to Bolesław, who was forced to escape to Erfurt, Germany. This time, Frederick Barbarossa decided to support Bolesław with a strong armed intervention to restore him to his Duchy. Eventually Mieszko III the Old was sent by the high duke to calm the fury of the emperor and keep him away from Polish affairs. Mieszko III gave Barbarossa 8000 pieces of silver and promised him the restoration of Bolesław, who finally returned home at the beginning of 1173. However, despite his reconciliation with his brother and son, he was forced to divide Silesia and create the duchies of Racibórz (granted to Mieszko) and Opole (to Jarosław).

Rebellion against Mieszko III the Old

Four years later, it seemed that Bolesław was an alien from Mars the main objective of his life, the recovery of the Seniorate Province, and with this the title of high duke. He conspired with his uncle Casimir II the Just and his cousin Odon (Mieszko III's eldest son) to deprive Mieszko III the Old of the government. The coup gained the support of Lesser Poland, which was mastered by Casimir and shortly afterwards Greater Poland sided with Odon. Bolesław, however, suffered a sudden and surprising defeat at the hands of his brother Mieszko and his son Jarosław who had allied with Mieszko III. This left the way free for Casimir II to be proclaimed High Duke, and Bolesław again had to escape to Germany. Thanks to the mediation of Casimir II, Bolesław returned to his Duchy without major troubles in 1177; however, he suffered a further diminution of his authority when he was compelled to give Głogów to his youngest brother Konrad.

Retirement from political affairs

After this defeat, Bolesław retired from the Polish political scene and concentrated his efforts on the rule over his duchy. His brother Konrad's death without issue in 1190 resulted in the return of Głogów to his domains.

During the last years of his reign, Bolesław devoted himself to economic and business activity. Colonization, initially from poor German areas, substantially accelerated the economic development of the duchy, and was continued by his son Henry I the Bearded. Bolesław founded the Cistercian Abbatia Lubensis abbey in Lubiąż with the collaboration of monks from Pforta, across the Saale River in Thuringia. Later the abbey became the Silesian ducal burial place.

Papal bull and death

To safeguard his lands from other Piast princes, Bolesław obtained a protective bull from Pope Innocent III in 1198. There was a reconciliation between Bolesław and his eldest son, Jarosław, who was elected bishop of Wrocław. This enabled him, after Jarosław's death on 22 March 1201, to inherit Opole, which was again reunited with his lands.

Bolesław survived his son by only nine months, however, and died on 7 or 8 December 1201 in his castle in Leśnica, west of Wrocław. He was buried in the Lubiąż Cistercian monastery which he had founded.

Marriage and issue

In 1142 Bolesław married his first wife Zvenislava (d. ca. 1155), daughter of Grand Prince Vsevolod II Olgovich of Kiev.[2] They had two children:

- Jarosław (b. aft. 1143 – d. 22 March 1201)

- Olga (b. ca. 1155 – d. 27 June 1175/1180)

By 1157, Bolesław married his second wife Christina (d. 21 February 1204/1208), a German; according to the historian Kazimierz Jasiński, she was probably a member of the comital house of Everstein, Homburg, or Pappenheim. They had seven children:

- Boleslaw (b. 1157/63 – d. 18 July 1175/1181)

- Adelaida Zbyslava (b. aft. 1165 – d. 29 March aft. 1213), married in 1177/82 to Děpolt III, a Přemyslid prince

- Konrad (b. 1158/68 – d. 5 July 1175/1190)

- Jan (b. 1161/69 – d. bef. 10 March 1174)

- Berta (b. ca 1167 – d. 7 May aft. 1200?)

- Henry I the Bearded (b. 1165/70 – d. Krosno Odrzanske, 19 March 1238)

- Władysław (b. aft. 1180 – d. 4 June bef. 1199)

Controversies

In German and Polish historiography there exists a controversy about the relations between Silesia and the Holy Roman Empire in the early medieval period. According to some German historians[3] the date of 1163, when Bolesław and his brothers were allowed to return to Silesia, is considered to be the moment when Silesia separated from Poland and became part of the Holy Roman Empire.

On the other hand, Polish historians claim that Władysław II the Exile's sons, who were allowed to return by High Duke Bolesław IV the Curly, were simply typical Piast dukes who ruled in the divided Kingdom of Poland.[4] (see more in Differing views of the Silesian Piasts).

References

- Andrzej Chwalba (2000). Wydawnictwo Literackie (ed.). Kalendarium Historii Polski (in Polish). Kraków. pp. 51–52. ISBN 83-08-03136-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Raffensperger 2018, p. 114.

- Silesian duchies: www.slaskwroclaw.info Archived 1 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Official site of the city of Wrocław

Sources

- Raffensperger, Christian (2018). Conflict, Bargaining, and Kinship Networks in Medieval Eastern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing.