Bombing of the Banski Dvori

The bombing of the Banski Dvori (Croatian: bombardiranje Banskih dvora) was a Yugoslav Air Force strike on the Banski Dvori in Zagreb—the official residence of the President of Croatia at the time of the Croatian War of Independence. The airstrike occurred on 7 October 1991, as a part of a Yugoslav Air Force attack on a number of targets in the Croatian capital city. One civilian was reported killed by strafing of the Tuškanac city district and four were injured.

| Bombing of the Banski Dvori | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Croatian War of Independence | |

Hrvoje Knez's photo of smoke rising after the explosion at Banski Dvori on 7 October 1991 (exhibit in Zagreb City Museum; includes examples of destroyed furniture from the building) | |

| Type | Airstrike |

| Location | 45°48′59″N 15°58′23″E |

| Target | Banski Dvori |

| Date | 7 October 1991 |

| Executed by | |

| Casualties | 1 civilian killed 4 civilians injured |

At the time of the attack, Croatian President Franjo Tuđman was in the building, meeting Stjepan Mesić, then President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia, and Ante Marković, then Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, but none of them were injured in the attack. In immediate aftermath, Tuđman remarked that the attack was apparently meant to destroy the Banski Dvori as the seat of the statehood of Croatia. Marković blamed Yugoslav Defence Secretary General Veljko Kadijević, who denied the accusation and suggested the event was staged by Croatia. The attack prompted international condemnation and consideration of economic sanctions against Yugoslavia. The presidential residence was immediately moved to the Presidential palace, which was formerly known as Villa Zagorje. The Banski Dvori sustained significant damage, but repairs started only in 1995. The building later became the seat of the Croatian Government.

Background

In 1990, the first multi-party elections were held in Croatia, with Franjo Tuđman's win raising nationalist tensions further in an already tense SFR Yugoslavia.[1] The Serb politicians left the Sabor and declared the autonomy of areas that would soon become part of the unrecognized Republic of Serbian Krajina, which had the intention on achieving independence from Croatia.[2][3] As tensions rose, Croatia declared independence in June 1991. However, the declaration was suspended for three months, until 8 October 1991.[4][5] The suspension came about as the European Economic Community and the Conference on Security and Cooperation in Europe urged Croatia that it would not be recognized as an independent state because of the possibility of a civil war in Yugoslavia.[6] The tensions escalated into the Croatian War of Independence when the Yugoslav People's Army and various Serb paramilitaries mobilized inside Croatia.[7] On 3 October, the Yugoslav Navy renewed its blockade of the main ports of Croatia. This move followed months of standoff and the capture of Yugoslav military installations in Dalmatia and elsewhere. These events are now known as the Battle of the barracks. That resulted in the capture of significant quantities of weapons, ammunition and other equipment by the Croatian Army, including 150 armoured personnel carriers, 220 tanks and 400 artillery pieces of 100-millimetre (3.9 in) caliber or larger,[8] 39 barracks and 26 other facilities including two signals centres and a missile base.[9] It also coincided with the end of Operation Coast-91, in which the Yugoslav forces failed to occupy the coastline in an attempt to cut off Dalmatia's access to the rest of Croatia.[10]

Warning of the attack

According to Martin Špegelj, the Defence Minister of Croatia between August 1990 and July 1991, the Croatian Army was informed by a Yugoslav Air Force Željava Air Base-based source about a top secret mission prepared for the next day, but Špegelj claims that the information was not taken seriously due to lack of details.[11] Other sources assert that a warning was conveyed by Croatian security and intelligence system services,[12] indicating the Soviet Union and its then-president Mikhail Gorbachev as the source of the information.[13] At midnight during the night of the 6–7 October, the Soviet ambassador to Belgrade was reported to have received government instructions to warn the Yugoslav military against attacking Zagreb.[14]

Tuđman spent the night in a Croatian Air Force and Air Defence command post—a tunnel running under the Gornji Grad—where information on the movement of Yugoslav aircraft was relayed. In the morning, Yugoslav General Andrija Rašeta informed the press that his superiors may decide to attack Zagreb as a form of pressure on Tuđman.[15] Three air raid alarms were sounded during the morning of 7 October because the Yugoslav Air Force deployed as many as 30 to 40 combat jets in the Zagreb area, and numerous tip-offs of imminent air raids were received from Yugoslav military bases. During the morning, Yugoslav Air Force jets were observed taking off from bases near Pula and Udbina in Croatia and Banja Luka in Bosnia and Herzegovina. No flights were recorded taking off from Željava Air Base, presumably because of low cloud cover in the area. At 1:30 pm, the Croatian Army captured a Yugoslav military communications centre and radar post near Velika Buna, south of Zagreb, hindering Yugoslav Air Force control of aircraft in the area. It is believed that the event affected the timing of the raid on the Banski Dvori,[12] the official residence of the President of Croatia at the time.[16]

Bombing

Approximately at noon of 7 October 1991, Tuđman met with Stjepan Mesić, then President of the Presidency of Yugoslavia and Ante Marković, then Prime Minister of Yugoslavia, both ethnic Croats, in the Banski Dvori.[17] The purpose of the meeting was to persuade Marković to leave his position as the head of the Yugoslav federal government, which he appeared reluctant to do,[18] and to discuss the need for Croatia's independence.[19] The meeting was adjourned for lunch that was to be attended by presidential aides. Tuđman made another effort at persuading Marković, trying to appeal to his Croatian origin. The three left the lunch as dessert was being served and moved into the president's office to continue their discussion. After Tuđman left the room, everyone else followed.[12]

Just after 3 pm, minutes after the lunch had ended, the Yugoslav Air Force attacked the Banski Dvori and other targets in the Gornji Grad area of Zagreb and elsewhere in the Croatian capital city, two or three minutes after everyone had left the hall where the lunch was hosted.[12] Zagreb was attacked by approximately 30 Yugoslav jets,[20] however the Gornji Grad raid was carried out by two Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21s carrying eight Munja 128-millimetre (5.0 in) unguided missiles each and two Soko G-4 Super Galebs carrying two Mark 82 bombs each.[18][21] The Banski Dvori building was struck by the Mark 82 bombs set off by proximity fuzes 5 metres (16 feet) above the target,[12] scoring two direct hits.[13]

One civilian was reported killed by the aircraft strafing of the Tuškanac area of Gornji Grad.[22] None of the three leaders was injured,[23] but four people were wounded in the attack.[24] The facade of the Banski Dvori and nearly all its rooms were damaged, and a part of its roof structure was destroyed.[25] The first estimates of the damage inflicted on the building and its contents ranged between 2 and 3 million US dollars. Apart from the Banski Dvori, other buildings in the area sustained damage. Those included the Croatian Parliament building, the Old City Hall, St. Mark's Church, the Museum of History, the Institute for the protection of cultural monuments as well as residences and offices in the vicinity,[20] including the residence of Swiss consul Werner Mauner.[24]

Aftermath

In a television report taped and broadcast shortly after the bombing, Tuđman said that the attack appears to have been meant to destroy the Banski Dvori as the seat of the statehood of Croatia, and as a decapitation strike. He concluded with statements of resolve to end foreign occupation and rebuild the nation.[26] Marković telephoned his office in Belgrade blaming Yugoslav Defence Secretary General Veljko Kadijević for the attack. He demanded his resignation, threatening not to return to Belgrade until Kadijević was out of office. The Yugoslav Defence Ministry brushed away the accusation, claiming that the attack was not authorized by the central command and suggesting that the event might have been stage-managed by the Croatian authorities.[17] The Yugoslav military later suggested that Croatian leadership planted plastic explosives in the Banski Dvori.[24]

In response to the situation, the United States consulate advised American nationals, including journalists, to leave Croatia. The US State Department announced that it would consider introducing economic sanctions against Yugoslavia.[15] Germany condemned the attack, calling it barbarous, and blamed it on the Yugoslav military.[27]

On 8 October 1991, as the independence declaration moratorium expired, the Croatian Parliament severed all remaining ties with Yugoslavia.[28] That particular session of the parliament was held in the INA building in Šubićeva Street in Zagreb due to security concerns provoked by the recent air raid;[29] Specifically, it was feared that the Yugoslav Air Force might attack the parliament building.[30]

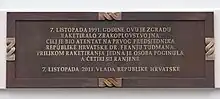

After the bombing, the residence of the President of Croatia was moved from the Banski Dvori to the Presidential palace—formerly known as Villa Zagorje—in the Pantovčak area of Zagreb.[16] Funds to repair the Banski Dvori were approved in 1995,[31] and the site became the official residence of the Croatian Government.[32] A plaque commemorating the bombing was placed at the Banski Dvori facade 20 years after the attack, in 2011.[33] The bombing is also commemorated by the Zagreb City Museum as the event is featured in the Zagreb in Independent Croatia collection of its permanent display.[34]

Footnotes

- The Independent & 13 December 1999.

- The New York Times & 2 October 1990.

- EECIS 1999, pp. 272–278.

- The New York Times & 26 June 1991a.

- Sabor & 7 October 2004.

- The New York Times & 26 June 1991b.

- The New York Times & 4 November 1991.

- Jutarnji list & 25 May 2011.

- MORH 2011, p. 13.

- The New York Times & 3 October 1991.

- Špegelj 2001, p. 148.

- Večernji list & 7 October 2012.

- Jutarnji list & 7 October 2012.

- Boca Raton News & 8 October 1991.

- Chicago Tribune & 8 October 1991.

- Jutarnji list & 25 August 2009.

- The New York Times & 8 October 1991.

- Nova TV & 7 October 2012.

- Nova TV & 7 October 2011.

- Radović 1993, pp. 122–123.

- Banković 2004.

- Kostović, Judaš & Adanić 1993, p. 279.

- Los Angeles Times & 8 October 1991.

- Nova TV & 7 October 2009.

- HRT & 7 October 2012.

- Index.hr & 7 October 2012.

- AP News & 7 October 1991.

- Narodne novine & 8 October 1991.

- Sabor & 7 October 2008.

- Glas Slavonije & 8 October 2011.

- Nacional & 8 April 2003.

- Croatian Government & 6 May 2007.

- Novi list & 8 October 2012.

- Zagreb City Museum.

References

- Books and scientific journal articles

- Kostović, Ivica; Judaš, Miloš; Adanić, Stjepan (1993). Mass killing and genocide in Croatia 1991–92 : a book of evidence, based upon the evidence of the Division of Information, the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Croatia. Hrvatska Sveučilišna Naklada. OCLC 28889865.

- Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States. London, England: Taylor & Francis. 1999. ISBN 978-1-85743-058-5.

- Radović, Darja (1993). "Report on the air raid on Zagreb-Gornji grad (the Upper Town) on October 7th 1991" (PDF). Radovi Instituta Za Povijest Umjetnosti. Institut za povijest umjetnosti. 17 (1). ISSN 0350-3437. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2018-11-19.

- Špegelj, Martin (2001). Žanić, Ivo (ed.). Sjećanja vojnika [Memories of a Soldier] (in Croatian). Zagreb, Croatia: Znanje. ISBN 9789531952064.

- News reports

- "21. obljetnica raketiranja: Gorbačov spasio Tuđmana, Mesića i Markovića od atentata!" [The 21st anniversary of the rocket attack: Gorbachev saved Tuđman, Mesić and Marković from the assassination attempt!] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. 7 October 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2012.

- "Barbari su pokušali obezglaviti Hrvatsku, a postigli su suprotno – još veće jedinstvo hrvatskog naroda!" [Barbarians tried to decapitate Croatia and achieved the opposite – even greater unity of Croatian nation!] (in Croatian). Index.hr. 7 October 2012. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013.

- Boroš, Dražen (8 October 2011). "Dvadeset godina slobodne Hrvatske" [Twenty years of free Croatia] (in Croatian). Glas Slavonije.

- "Državni vrh srećom preživio raketiranje Banskih dvora" [Country leadership lucky to survive rocket attack on Banski dvori] (in Croatian). Nova TV (Croatia). 7 October 2009. Archived from the original on 9 March 2012.

- "Gorbachev tells Yugoslavs to end attack". The Washington Post. Boca Raton News. 8 October 1991.

- Ivanković, Davor (7 October 2012). "Tuđmana spasila dojava, JNA ga gađala američkim bombama" [Tuđman saved by a tip-off, Yugoslav People's Army targeted him with US bombs] (in Croatian). Večernji list. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012.

- Krajač, Tatjana (7 October 2011). "Da sam poginuo naslijedio bi me Srbin veći od svakog Srbina" [If I were killed, I would have been succeeded by a Serb that was the biggest nationalist than any other] (in Croatian). Nova TV (Croatia). Archived from the original on 14 October 2012.

- Moseley, Ray (8 October 1991). "Croatian Capital Hit By Missiles". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013.

- Magas, Branka (13 December 1999). "Obituary: Franjo Tudjman". The Independent. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2011.

- "Na današnji dan raketirani Banski dvori: Tuđman, Mesić i Marković slučajno izbjegli atentat" [Anniversary of Banski dvori missile attack: Tuđman, Mesić and Marković avoid assassination by chance] (in Croatian). Nova TV (Croatia). 7 October 2012. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012.

- Nezirović, Vanja (25 August 2009). "Ne dolazi u obzir da se odreknemo Pantovčaka" [Giving up Pantovčak is out of the question] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013.

- "Obljetnica raketiranja Banskih dvora" [Anniversary of Banski dvori rocket attack] (in Croatian). Croatian Radiotelevision. 7 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-02-17. Retrieved 2012-10-07.

- Ožegović, Nina (8 April 2003). "Prije je krađa u Banskim dvorima bila nemoguća: na ulazu su se strogo kontrolirali svi, od službenika i novinara do ministara" [Theft used to be impossible in Banski dvori: everyone was strictly controlled at the entrance, including clerks, journalists and ministers] (in Croatian). Nacional (weekly). Archived from the original on 3 December 2013.

- Pavelić, Boris; Ponoš, Tihomir (8 October 2012). "Otkrivena spomen-ploča ispred Banskih dvora, Mesić i Marković nisu bili pozvani" [Banski dvori commemorative plaque installed, Mesić and Marković were not invited] (in Croatian). Novi list. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012.

- Riding, Alan (26 June 1991). "Europeans Warn on Yugoslav Split". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013.

- Starcevic, Nesha (7 October 1991). "Yugoslav Warplanes Attack Zagreb, Nearly Hit Politicians". Associated Press. Archived from the original on 9 October 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (2 October 1990). "Croatia's Serbs Declare Their Autonomy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 November 2012. Retrieved 11 December 2010.

- Sudetic, Chuck (26 June 1991). "2 Yugoslav States Vote Independence To Press Demands". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 10 November 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (4 November 1991). "Army Rushes to Take a Croatian Town". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 July 2012.

- Sudetic, Chuck (3 October 1991). "Navy Blockade of Croatia Is Renewed". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 14 June 2013.

- Williams, Carol J. (8 October 1991). "Croatia Leader's Palace Attacked". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 22 October 2013.

- "Yugoslav Planes Attack Croatian Presidential Palace". The New York Times. 8 October 1991. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013.

- Žabec, Krešimir (25 May 2011). "Tus, Stipetić, Špegelj i Agotić: Dan prije opsade Vukovara Tuđman je Imri Agotiću rekao: Rata neće biti!" [Tus, Stipetić, Špegelj and Agotić: A day before the siege of Vukovar, Tuđman told Imra Agotić: There will be no war!] (in Croatian). Jutarnji list. Archived from the original on 21 April 2012.

- Other sources

- "44. Zagreb in Independent Croatia". Zagreb City Museum. Archived from the original on 23 June 2013.

- Živojin Banković (2004). "Lovac presretač MiG-21" [Fighter interceptor MiG-21] (in Serbian). Archived from the original on 10 April 2012.

- "Ceremonial session of the Croatian Parliament on the occasion of the Day of Independence of the Republic of Croatia". Official web site of the Croatian Parliament. Sabor. 7 October 2004. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 7 October 2012.

- "Govor predsjednika Hrvatskog sabora Luke Bebića povodom Dana neovisnosti" [Speech of Luka Bebić, Speaker of the Croatian Parliament on occasion of the Independence day] (in Croatian). Sabor. 7 October 2008. Archived from the original on 1 December 2013.

- Croatian Parliament (8 October 1991). "Odluka, Klasa: 021-03/91-05/07". Narodne novine (in Croatian). 1991 (53). Archived from the original on 2009-09-23.

- "Political Structure". Croatian Government. 6 May 2007. Archived from the original on 20 September 2013.

- "The Release of the Barracks" (PDF). 20 Years of the Croatian Armed Forces. Hrvatski vojnik. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-10-08. Retrieved 2012-10-12.