Bondelswarts Rebellion

The Bondelswarts Rebellion in 1922 (aka the Bondelswarts Uprising or Bondelswarts Affair) was a controversial violent incident in South Africa's League of Nations Mandate of South West Africa, now Namibia.

In 1917, the South African mandatory administration had created a tax on dogs, and they increased it in 1921.[1] The tax was rejected by the Bondelswarts, a group of Khoikhoi, who were opposed to various policies of the new administration. They were also protecting five men for whom arrest warrants had been issued.[1]

There is disagreement over the details of the dispute, but according to historian Neta Crawford, "most agree that in May 1922 the Bondelswarts prepared to fight, or at least to defend themselves, and the mandatory administration moved to crush what they called a rebellion of 500 to 600 people, of which 200 were said to be armed (although only about 40 weapons were captured after the Bondelswarts were crushed)".[1]

Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr, the Mandatory Administrator of South West Africa, organised in 400 armed men, and sent in aircraft to bomb the Bondelswarts. Casualties included 100 Bondelswart deaths, including a few women and children.[1] A further 468 men were either wounded or taken prisoner.[1]

South Africa's international reputation was tarnished.[2] Ruth First, a South African anti-apartheid activist and scholar, describes the Bondelswarts shooting as "the Sharpeville of the 1920s".[3] It was one of the first uprisings to be examined by the Permanent Mandates Commission under the new League of Nations mandate system introduced after the First World War. The application of the principles set out in the League of Nations mandatory covenants by the independent Permanent Mandates Commission led to a deepened international examination of the ethics of colonialism and of the actions of taken against subject peoples.[1]

Deep roots of the 1922 rebellion

First contact with European settlers

The Bondelswarts (now the ǃGamiǂnun, a clan of the Nama people) initially inhabited a territory to the north and south of the Orange River, but as the Dutch administration at the Cape extended its sovereignty the Bondelswarts moved to the lands north of the Orange River to avoid interaction with the government of the Cape.[4] European traders came to Namibia in the early nineteenth century but they were few in number and their activities were relatively low key, although they did facilitate access to European guns and some European made goods.[5]

In the early 1820s, at the time of the first contact with missionaries, the Bondelswarts inhabited the territory stretching 200 miles to the north of the Orange River in current day Namibia.[6] The Bondelswarts were curious about Christianity – in 1827 Abraham Christian, the leader of the Bondelswarts, visited Leliefontein, the headquarters of the Wesleyan Missionary Society in Little Namaqualand in South Africa, and asked for a missionary to be sent to him.[7] However, it was not until 1834 that the Wesleyan missionary Reverend Edward Cook arrived with his wife to found the mission at Warmbad within the Bondelswarts territory.[7] Within nine years Reverend Cook reported a Christian congregation of over a thousand Bondelswarts converts.[8] However, Goldblatt comments that whilst Reverend Cook endeavoured to interest the Bondelswarts in Christianity, and could report baptisms and attendances at services, in fact little impact was made upon the people and none at all on their leader Abraham Christian.[7]

At first, contact with the Cape government was relatively remote. In 1830, Abraham Christian, as leader of the Bondelswarts, received a subsidy from the Cape government in return for not becoming involved in the disputes among the tribes further north, and for undertaking to suppress disturbances and to co-operate with the Cape government generally in preserving peace and order along the Orange River.[9] This arrangement was renewed in 1870 by Abraham Christian's grandson, Willem Christian, the new leader of the Bondelswarts, although the allowance was much reduced, being a mere £50 annually.[9]

By the mid-nineteenth century the number of traders had increased and their network extended as far north as Etosha.[5]

Land losses

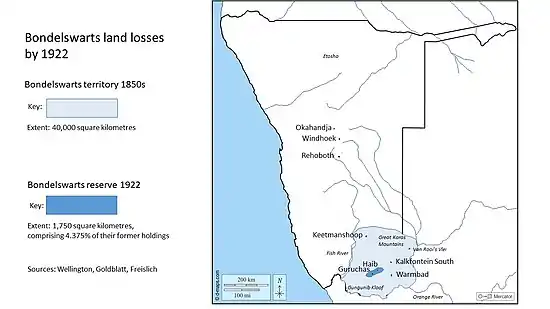

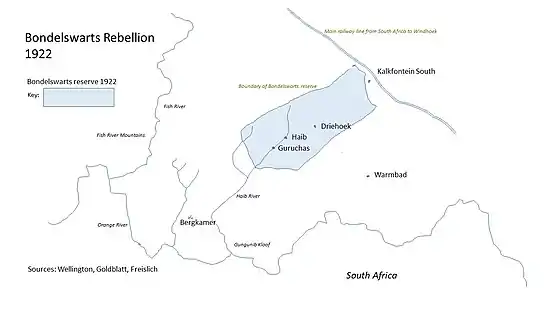

In the third quarter of the nineteenth century the area occupied by the Bondelswarts extended from the Orange River northwards to beyond the Great Karas Mountains and westwards to the Fish River, an area of 40,000 square kilometres (4 million hectares).[10] By the time of the 1922 Bondelswarts rebellion, over 95% of this land had been lost,[11] some by way of confiscation but also by way of sale.

In April 1890, Germany had signed a protection treaty with the Bondelswarts and the German flag had been hoisted in Warmbad.[8] In June 1890, Britain and Germany signed a treaty on their respective "spheres of influence" in Africa which included a detailed demarcation of the boundaries of the German Protectorate of South West Africa, and from this time the German annexation of the whole territory of South West Africa was recognised by the British and internationally.[8] For the Bondelswarts, one of their largest land losses came shortly thereafter, when the Bondelswarts and other indigenous groups "sold" 60,000 square kilometres of land to the English company Karas Khoma Exploration and Prospecting Syndicate.[12] This sale led to strong feeling among the Bondelswarts against their leader, Willem Christian, once the consequences of the sale became apparent. When Theodor Leutwein, the German colonial administrator, visited the Bondelswarts in 1895, he was surprised at the contents of the agreement, and could only attribute Willem's action to the fact that he was under the influence of alcohol at the time of signing. Leutwein resolved to remedy the inequitable results of the agreement at a later date,[13] although he never did so.

.jpg.webp)

Further land losses followed the first rising against German rule in 1898 when the Bondelswarts were discontent at being required to stamp their guns and possess gun licences in line with a newly promulgated law.[13] Leutwein hurried down south from Windhoek in September 1898 with an armed force to compel them to comply.[13] Willem Christian, still the Bondelswart leader, travelled to Keetmanshoop where Leutwein had gathered his forces.[13] There was an enquiry, ending in a court martial finding Willem Christian and others guilty of a breach of the protection treaty.[13] The Bondelswarts were condemned to pay the expenses of Leutwein's expedition and as they had no money had to cede to the German government the whole of Keetmanshoop and the grazing ground attached to it.[13]

1903-1906 Bondelswarts rebellion

In October 1903 a further Bondelswarts rebellion broke out. Foreshadowing the 1922 Rebellion, the 1903 revolt was tied up with the encroachment of white settlers on Bondelswarts territory and the heavy-handed intervention of the local police.[11]

Crawford's view is that one of the main contributing factors was the publication by the Germans shortly before the outbreak of regulations compelling that "(1) every coloured person must regard a white person as a superior being, and (2) in court the evidence of one white man can only be outweighed by the statements of seven coloured persons".[14]

The trigger event was a dispute between the Bondelswarts chief and the local German lieutenant over the sale of a goat. The lieutenant went with two or three others to arrest the chief, and in the ensuing fracas both the chief and the lieutenant were shot dead.[15] At that time the Bondelswarts were a small but very effective fighting force. They had around 400-500 fighting men armed with up-to-date breech-loading rifles, knew their territory very well, and were able to conduct very effective guerrilla warfare.[15] Leutwein decided to concentrate almost all his available forces against the Bondelswarts and personally went south to deal with the situation.[15] With Leutwein away, the chiefs and headmen of the Herero people met and decided to stake all on open war. They were a significantly larger force than the Bondelswarts – the Hereros had 7,000-8,000 fighting men, although not all had rifles.[15]

In January 1904, around 150 German settlers and traders had been killed by the Herero forces, many in Okahandja.[15] Realising the seriousness of the Herero situation, Leutwein hastily concluded a truce with the Bondelswarts, requiring them to give up their arms and ammunition.[16] As compensation for the costs of the expedition the Bondelswarts were required to give up to the German administration a further portion of the tribal lands, fostering further discontent among the Bondelswarts.[16]

The Herero uprising resulted in the end of Leutwein's colonial leadership and he was replaced by the notorious General Lothar von Trotha, who even at the time of his appointment had a reputation for utterly ruthless methods with native rebels,[15] and was largely responsible for the Herero and Namaqua genocide between 1904 and 1906. Von Trotha's approach was unforgiving. He told Leutwein in 1904: "I know enough tribes in Africa. They all have the same mentality insofar as they yield only to force. It was and remains my policy to apply this force by unmitigated terrorism and even cruelty. I shall destroy the rebellious tribes by shedding rivers of blood and money".[14] This contrasted strongly with the measured approach of the Herero chiefs, who at their meeting before the outbreak had specifically resolved to limit their attack to German men of military age, and that no women or children were to be harmed.[15]

Von Trotha followed this with his infamous proclamation of 2 October 1904 which stated: "The Herero people must now leave the country… every Herero, with or without a rifle, will be shot. I will not take over any more women and children, but I will either drive them back to their people or have them fired on".[15] Many Germans objected to the policy of exterminating the Herero, including the chancellor, Prince Bernhard von Bülow, who argued to Kaiser Wilhem II that the order was "contradictory to all Christian and humane principles".[14] However, von Bülow did argue rather pragmatically that extermination was unwise since the native population was an essential source of labour for farming and mining.[14] In December 1904 von Trotha's extermination order was countermanded, though much of the damage had already been done.[14] Von Trotha was withdrawn from South West Africa in November 1905.[14] According to Crawford, about 50% of the Nama and 75% to 80% of the Herero population had been killed by German forces by the end of 1905.[14]

Notwithstanding the 1904 treaty, the Bondelswarts, including Jacob Morenga, continued the rebellion later that year and attacked the German garrison at Warmbad in November 1904 inflicting severe losses.[15] Thereafter Morenga established himself with 500 – 800 riflemen in the Great Karas Mountains from where he was able to plunder the lowlands and harry the German posts and garrison for many months, until his defeat at Van Rooi's Vlei in May 1906.[15] Thereafter, the Bondelswarts chief Johannes Christian held out against the German forces until October 1906 when he made overtures for peace.[15]

Under the peace treaty signed in December 1906 the Bondelswarts were confined to a reserve of 175,000 hectares [11] (1,750 square kilometres), or 4.375% of their original holdings. Nonetheless, the peace treaty was on more generous terms than many other tribal groups received.[17] The Bondelswarts leadership continued to be recognised, and they were given stock to enable them to live.[17] Other groups involved in the rebellion forfeited all of their lands and their leadership ceased to be recognised.[17]

Following the rebellion the German authorities allowed the British Karaskoma Syndicate to select 12,800 square kilometres of farmland in the area.[15] Wellington states that the selection by the syndicate of the best farmland, and the acquisition of the best watering places, was considered later to be one of the deepest causes of the 1922 Bondelswarts rebellion.[15]

South African takeover 1915

Once the Union of South Africa had decided to support the Allies in the First World War the South African army invaded South West Africa and defeated the German forces in July 1915. The peace treaty allowed the German population to carry on farming and trading but the territory was subject to martial law.[18]

Following their victory, the South Africans promoted themselves as the liberators of the indigenous peoples.[19] South Africa appointed Sir EHL Gorges as the territory's military administrator. Gorges repealed the most draconian German laws including laws allowing flogging of non-whites and restricting non-white movement and stock-holding.[20] Lord Buxton, the Governor-General of South Africa, visited South West Africa in 1915 and "addressed the Natives at all important centres and on each occasion promised the Natives the old freedom along with great possessions of land an unlimited herds of cattle."[19] Non-whites without land were given temporary reserves on vacant farmland of good quality within their former tribal areas, and were protected from ill treatment at the hands of their former masters.[18] This treatment, and the promises made by the Governor-General, left them with the impression that they would have their former tribal areas returned to them.[18]

The Allies denounced the German colonial system. This rang true with the indigenous peoples of South West Africa who had experienced the horrors themselves. In Ruth First's view: "They saw victory, in their innocence, as a release. The German occupiers had stolen their lands, and then had themselves been displaced by armies fighting under the banners of justice. It seemed to the non-whites only just that their release from German rule should mean the restoration of the independence that they had enjoyed in the pre-German times. The South African forces had invaded the country as liberators; who were to be liberated if not the Herero, the Nama, all those in bondage?" [3] Of course at the end of the First World War all those members of the Bondelswarts who were over 35 years old could remember the days of their complete independence.[21]

A special commission of inquiry was appointed to examine conditions under German rule.[3] South Africans took evidence from the non-whites of the treatment they had received at the hands of the Germans and created the impression that things would be different under South African rule.[19] Herero chiefs, Nama spokesmen, prisoners of war and others detailed the horrors of those years. The report, the infamous "Imperial Blue Book" produced in Windhoek in 1918, comprised a 220-page heavily illustrated indictment of Germany's harsh, even genocidal regime.[20] The report detailed the German military operations against the tribes, with pictures of the crude executions, neck chains, leg and arm fetters, the flayed backs of women prisoners and Herero refugees returning starved from the desert.[3] The Imperial Blue Book set out to convince the world how unsuitable the Germans were to govern natives, and manifestly achieved its purpose. Ruth First comments that when Britain and South Africa put on display the results of Germany's colonial policy, it was not because they wanted to champion the African cause, but because they wanted to discredit the German one.[3] However, the pacification of Algeria by the French, the rule of King Leopold's rubber regime in the Congo, the exploitation by the Portuguese, English and Dutch of the slave trade on the west coast of Africa were no less ugly.[3] But Germany had entered the scramble for Africa in the last stages of colonisation, at a time when international morality had at last opened its eyes, and what others had done before in secret or in silence could not be done without discovery.[3] (In 1926, once the 1918 Imperial Blue Book had served its primary purpose of removing German control, the South West African Legislative Assembly adopted a resolution to the effect that copies of the Imperial Blue Book should be removed from official files and libraries and destroyed.) [22]

At the end of the war, over six thousand German citizens, representing around half of the colony's German population, were repatriated from Namibia.[22] The South African administrators found themselves in the unusual situation of being faced with not only a hostile, or potentially hostile, black population, but in the remaining German population, a hostile, or potentially hostile, white population.[22] The possibility of a black rebellion therefore posed a double threat to the military administration as in addition to the threat posed by the black rebellion the German community might take advantage of the opportunity to rebel against the occupying forces and reintroduce German rule.[22] Appeasement of the white settler interests undoubtedly resulted in harsher treatment of the indigenous peoples in the early 1920s. Many of the demands made by the white settlers during the military period for more land, tighter control of the labour force, branding laws, a heavier dog tax and others were introduced during the first five years of the League of Nations Mandate. The tentative liberalism of the military administration disappeared and white settler interests once more reigned supreme.[22]

League of Nations Mandate 1920

After the First World War the League of Nations was established with its principle mission being to maintain world peace. South Africa was granted the Mandate to administer South West Africa under Article 22 of the Covenant of the League of Nations (which came into force in January 1920), which stated that in respect of Mandates for colonies inhabited "by peoples not yet able to stand by themselves under the strenuous conditions of the modern world, there should be applied the principle that the well-being and development of such peoples form a sacred trust of civilisation". Article 2 of the Mandate for South West Africa states that the "Mandatory shall have full power of administration and legislation over the territory … [and shall] promote to the utmost the material and moral well-being and the social progress of the inhabitants". These were the underlying principles upon which South Africa was obliged to govern South West Africa.[18]

To allow monitoring and to ensure compliance, annual reports were to be submitted to the Permanent Mandates Commission of the League of Nations.[18] The Permanent Mandates Commission sat in Geneva and met twice a year. The majority of members consisted of non-Mandatory Powers.[1] For the first time, the performance of the administration of the territory would be subject to independent international scrutiny and not just review by the colonial power itself. Also for the first time, the principles and beliefs that were essential elements of a decolonisation regime – self-determination, nationalism, human rights and an international interest in the affairs of colonial administration were codified in the League of Nations treaty and used to structure international relations.[1] The greatest power of the Mandate system to change colonial practice lay in the Permanent Mandates Commission, whose official role was oversight, but it became a venue for ethical argument, and perhaps inadvertently promoted the deconstruction of colonialism and the construction of a new paradigm.[1] With the creation of the Permanent Mandates Commission, the regime created was not what its founders had imagined; it was not a structure for imperial collaboration but rather "a polyvalent force-field of talk, one that amplified the voices of non-imperial states and even of colonised peoples".[23]

Lawyer turned historian Israel Goldblatt points out "there was the obvious dilemma of entrusting a Mandate, which emphasizes the primary interest of the Natives, to a Mandatory whose Government was dependent on the votes of its own white electorate, which was concerned primarily with white man's interests.[24]

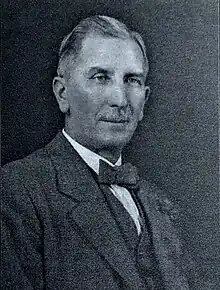

In October 1920,the Union of South Africa's government appointed Gysbert Reitz Hofmeyr as the first non-military Administrator of South West Africa.[18] Although the appointment later aroused criticism, when General Jan Smuts, the Prime Minister of South Africa, and a key figure in the founding of the League of Nations, made the choice he had good motives and good reasons.[25] Hofmeyr was a Cape man of liberal education and outlook and of wide administrative experience in the Cape, the Transvaal, and the Union of South Africa.[25] For many years Hofmeyr had been the respected Clerk of the Union House of Assembly, and had come to Smuts originally on the strong recommendation of John X. Merriman, a former Prime Minister of the Cape of Good Hope, and had always proved himself trustworthy and intelligent.[25]

The security of tenure that came with the Mandate meant that notwithstanding the language of the Mandate the new civilian administration initially did not feel the need to pander to international opinion by presenting a liberal image to the world.[22] The German settlers could be welcomed back into the fold as fellow whites and colonial masters. There was no longer a perceived need, as there had been in the military period, to depict the German settlers as brutal and vicious in their treatment of blacks.[22]

In 1921, an advisory council was appointed to represent settler interests and in his annual report for that year the Administrator stated that he had sought the advice of the council on a number of issues including native reserves, the pass laws, the Master and Servants Proclamation, the branding of stock and the dog tax.[22] After analysing the land set aside for reserves and the land granted to white settlers, Emmett comments that the fact that about 28 times more land per person was allocated to white settlers during the first five years of the Mandate than was allowed for all blacks in the police zone in the same period provides a rough but clear indication of the administration's priorities.[22]

Hofmeyr felt that the "sacred trust" of the Mandate referred to the prevention of blacks from obtaining arms and ammunition or liquor, but did not exclude the extension of the Union native policy of segregation to South West Africa, which he felt was in harmony with the terms of the Mandate.[26] This approach would lead directly to the Bondelswarts rebellion.

Immediate causes of the 1922 rebellion

Further Bondelswart land losses

In 1918 and 1919, increasing numbers of white South Africans moved to South West Africa to take advantage of the new opportunities. A large number of temporary grazing licences in relation to the southern districts (including the Bondelswarts territory) were issued to trek-boers from South Africa.[18] Following his appointment Hofmeyr's administration swiftly began demarcating landholdings, arranging loans and advertising for South African settlers.[20] In 1920 a Land Board had been set up and in the same year some 80 farms in the Warmbad and Keetmanshoop districts in the former Bondelswarts area were advertised.[18] The new Administration could not do enough for the new farmers; it gave them generous loan terms, granted them remissions on rent arrears, built dams, bored for water and advanced capital for stock.[3] Land hungry South Africans, spilling across the border, were allocated huge farms, virtually for the asking, that were then petted and pampered into eventual solvency.[3]

In his 1921 Report, the Administrator states that "at this late stage … there are difficulties in the way of procuring sufficient or suitable ground for Natives on account of the vested rights having to be considered".[27] Wellington asks what "at this late stage" can mean, given that this is the first year of the mandate and already we are told that "vested interests" (being German farms and the 169 farms allocated to white South African settlers in 1920) make it difficult to find good land for the "native" reserves.[18] Wellington's view is that "in applying the Mandate the white man's first acts reveal him using the screen of "vested interests" to conceal his decision to put the whites’ interests first and foremost and to fob off on the Native the poor land that the whites scorn to occupy."[18] Emmett points out that in 1924 the Administrator stated in his annual report that there were "hundreds of good farms" still awaiting settlers, and Emmett comments that there were clearly different standards governing the availability of land for blacks and whites in the territory.[22]

Although "native reserves" were set aside, those were often too small and too arid to support flocks.[20] In the Administrator's report of 1922 it is observed that the areas for native reserves have "been selected with every care and consideration so as to obviate, as far as human agency can prevent, the occupants from being disturbed even in times of the most severe drought."[28] Ruth First comments that the land was "selected with every care and consideration", perhaps, but only so as to obviate any conflict with the expansion of white settlement.[3]

In 1922, the Native Reserves Commission recommended a mere 10% of the land in the centre and south of the country for indigenous peoples to live on – 5 million hectares out of 57 million in all. But the actual proclamation made by the Administration was even worse: it gave Africans only 2 million hectares. Blacks (including so-called Coloureds) formed 90% of the population,[29] but were confined to 3.5% of the land.

The reserves allocated to blacks were never able to sustain their populations by design as they were always intended to be pools of labour from which black workers would come to the so-called white areas – the mines, railways, developing industries and farms.[29] By confining blacks to these areas the South African regime and white settlers avoided having to pay wages that would support a black worker and his/her family, and avoided the costs of proper housing, sanitation, health care and social provision.[29]

The Bondelswarts felt that the Germans, who had previously taken their land, had been defeated, and so this should result in the reinstatement of the lands already lost. In the 1922 Report of the Administrator for the South African Parliament and the Permanent Mandates Commission Hofmeyr states that "the Natives who of course had been the original owners of the land which had as a result of war been confiscated by the German Government, cut up into farms and sold or allotted to Europeans, had formed the expectation that this Administration, as the natural result of the war, would similarly confiscate German owned farms and thus the Natives would recover the lost land and homes previously occupied by them.[28] Emmett reflects that as late as 1946 a Herero witness had said to Michael Scott, a promoter of Namibian independence, that "What we don't understand is that when two nations have been at war, such as Britain or Germany or Italy, and when or other of those nations is defeated the lands belonging to the nation are not taken away from them…. The African people, although they have always been on the side of the British people and their allies, yet have their lands taken away from them and are treated as though they had been conquered".[22] It would be hard to find a better summary of the disillusionment felt.

The 1922 Report of the Administrator continues: "Almost without exception each section asked for the allotment of the old tribal areas, in which vested rights had accrued and the utmost difficulty was experienced in making them realize the utter impossibility of complying with such a request".[28] In Wellington's view, the Administrator's statement that he experienced "the utmost difficulty" in making the Natives realise the "utter impossibility of complying with such a request" seems surely to point not to the Natives inferior comprehension but to the Whites’ calculated duplicity, pointing out that under the Mandate South Africa had been given, and accepted, the political conditions enabling it to give high priority to Native interests in South West Africa.[18]

These incursions on Bondelswarts land fed into the deep-seated dissatisfaction among the Bondelswarts at the time of the rebellion, and the introduction of settlers from South Africa and questions of sovereignty remained a bone of contention with the Permanent Mandates Commission for the next seven or eight years.[18]

Nonetheless, the fact that the Bondelswarts retained a territorial base (unlike many other tribes) not only contributed to the anxiety of the neighbouring settlers, thus increasing the tension that led to the 1922 Rebellion, but provided the essential social cohesion for the Bondelswarts to be able to conduct their resistance.[11]

Laws pressuring the Bondelswarts to provide labour to white settlers

The white settlers were soon desperate for labour, and Hofmeyr set to work constructing a mesh of legal, financial and bodily controls to force Africans into their service.[20] In his official Report for 1920 the Administrator said that the "native question" is "synonymous with the labour question", in that white settlers complained that a good deal of the potential labour in the country was not made available to them, and at the same time "natives" were complaining of ill treatment and insufficient wages.[30] Wellington comments that "one cannot help wondering what has happened to the "sacred trust of civilisation" upon which the mandate was based.[18]

The interests of white settler farmers played a central role in shaping the contract labour system.[22] The white settlers had clearly envisaged the creation of a stable class-structured society with the indigenous population as a dispossessed proletariat.[22] In addition to the levying of taxes, a number of other measures were introduced to increase the labour force for the benefit of the white settlers. In 1920 the Vagrancy Law (Proclamation 25 of 1920) made it a punishable offence for a person to "wander abroad" without "visibile lawful means or insufficient lawful means of support".[22] Magistrates were empowered to compel those convicted to work for farmers at a predetermined wage; this discretionary power developed into a fruitful source of farm labour.[31]

A Masters and Servants Proclamation of 1920 imposed criminal punishment on servants guilty of negligence, breach of duty, desertion and disobedience; the withholding of wages and unlawful dismissal were also penalised.[31] A 1922 proclamation established the South African "pass" system whereby Blacks, on pain of imprisonment, were compelled to carry a form of identity document and travel within South West Africa was forbidden without special permits.[31]

In February 1921, the Administrator visited the Bondelswarts and encouraged them to take jobs with the German and South African settlers. The Bondelswarts complained that the white employers often failed to pay their wages and flogged them, and they showed the Administrator the scars of these beatings.[18] When asked later by the Permanent Mandates Commission what steps had been taken the Administrator replied that he had given instructions to the local magistrate to see that they were protected in future.[18]

Dog tax

One way in which the Bondelswarts could avoid working for the white settlers was to hunt game with small packs of dogs.[18] Dogs were also essential for the protection of stock from jackals.[11] Under the German regime, the Germans had shot the hunting dogs when the Bondelswarts’ success in hunting had led to a reduction in the number of labourers offering services to settlers.[18]

In 1917, the South African military Administration had imposed a dog tax to achieve the same ends, with the rate of tax escalating rapidly for additional dogs owned.[18]

In 1920, the new Administrator toured the country and found that blacks and a "certain class of European squatters" were still making extensive use of dogs to hunt game, instead of earning a living by what Hofmeyr called "honest labour".[32] Farmers, particularly those in the south, put pressure on Hofmeyr to increase the dog tax so that blacks would be forced to seek work.[11] This tax was increased substantially in February 1921, turning it into an enormously punitive tax, which according to Emmett, was "absurdly high".[11] Susan Pedersen points out that the Administrator reported in 1922 that the average wages were 10-20 shillings per month, plus food, but that farmers were often unable to pay the wages.[20] The new dog tax, in other words, amounted to between one and two months wages for one dog, rising to the laughable amount of ten pounds, or as much as one or two years’ wages, for five dogs.[20] What is more, as the missionary Monsignor Kolikowski pointed out, the Bondelswarts were aware that in the Union the dog tax was two shillings and sixpence.[11]

The Bondelswarts complained but nonetheless sought to pay the tax. Cash was in short supply. During the early 1920s there were frequent complaints that the wages of farm labourers were paid in kind.[22] The Bondelswarts tried to raise cash by selling stock at the Warmbad stores. The prices offered were, they considered, unnecessarily low, and payable not in cash (which could be used to settle the tax) but in "good-fors".[33] The authorities were unsympathetic and more than 100 members of the tribe were sentenced to fines or imprisonment for 14 days.[18]

In David Soggot's view the levying of taxes on dogs contributed to pressures on blacks to enter the labour market; money now had to be earned to meet taxation demands.[31] This brought the Administration on to a collision course with the very wards whom it was presumed to care for in the exercise of a "sacred trust".[31] Hofmeyr later denied that the tax had been imposed to force blacks to seek work, claiming that its purpose was to protect game, although the evidence suggests otherwise.[11] Although the tax was reduced by half just before the outbreak of the 1922 rebellion, the harm had been done, and it was too late to avert the confrontation.[11]

Branding irons

Further irritation for the Bondelswarts arose from a branding regulation, where each stock owner was required to purchase his own branding iron from the Administration for thirty shillings.[18] White owners were given possession of their brands, but the branding irons purchased by the Bondelswarts were kept by the police [18] and could only be applied to animals by the police. This discrimination increased the Bondelswarts'resentment of the administration.

Mutual lack of trust

At the outbreak of the First World War the sympathies of the Bondelswarts were entirely with the South Africans and some of their leaders acted as guides to the South African forces.,[18] including Abraham Morris, one of the heroes of the 1903-1906 Bondelswarts uprising against the Germans.[24] Morris had a Scottish father, but was brought up among the Bondelswarts and identified as such.[34] After the First World War the Bondelswarts asked permission for the return to the tribe of Abraham Morris and Jacobus Christian, son of their leader Willem Christian.[18] The military Administrator refused based on the opinions of white settlers in the area, and the headmen the Administrator appointed as leaders were not respected by the tribe.[18]

When Jacobus Christian returned in 1919 without first obtaining the military Administrator's permission the police invited him to visit the magistrate in Warmbad and then summarily arrested him on the road. The military Administrator censured the police for their action and allowed Christian to stay, but the incident left in the minds of the Bondelswarts a distrust of the local authority.[18] Further, repeated requests for the formal recognition of Jacobus Christian as "Kaptein" or tribal leader met with the Administrator's refusal, which resulted in a sullen attitude on the part of Jacobus and most of the Bondelswarts.[24]

The Bondelswarts were in constant conflict with the law, giving them a distorted concept of it.[26] An extract from the books of the Warmbad charge office between January 1920 and August 1922 shows that there had been twenty- two Bondelswarts sentenced for stock theft, fourteen for importing firearms without a permit, one hundred and seventy for failing to pay the dog tax, thirty-nine for entering South West Africa without a permit, and eighteen for importing stock into South West Africa without a permit.[26]

This meant that the later use of police in negotiations to defuse the discontent was almost certain to fail.

On the other hand, the white settlers had a similarly distorted fear of a general uprising. From the beginning of South African rule until the actual eruption of the 1922 rebellion, persistent reports of threatened uprisings had become a common feature in the white farming areas adjacent to the Bondelswarts reserve.[11] The characteristic response of the Administration was to dismiss such reports as a ploy by the German settlers who had been disarmed following the change of administration, to obtain arms and ammunition, or as an attempt to discredit the new Administration.[11] This did nothing to allay the sense of alarm that spread through the white community in the rural areas, and tended to make the administration less responsive to the very real grievances of indigenous communities such as that of the Bondelswarts.[11]

Economic pressures

By 1922, the territory, along with many other parts of the world, had entered the depths of the post-war recession.[22] The disbandment of the South African military garrison after the war meant that an important local market for farm produce was lost.[22] The end of the war had also seen the reorganisation of agriculture worldwide and the consequent contraction of markets for slaughter stock and other produce both in South Africa and overseas.[22] At the same time a severe drought overtook the territory - below average rains fell in southern Namibia between 1918 and 1922, culminating in a very severe drought in the 1921/ 1922 season which immediately preceded the outbreak of the rebellion.[11] The situation deteriorated further with the reversal of the inflow of capital from Germany to the territory and with the speculation in paper marks which resulted in numerous bankruptcies during the early 1920s.[22]

Major Manning, who had been appointed Native Commissioner for South West Africa, on a visit to the Bondelswarts’ reserve in 1921 was deeply struck by their poverty.[35] He found them "living chiefly on gum (acacia), goats, milk etc.", and reported that they stated that "in former years they had been able … to live fairly comfortably but owing to the smallness of wages and rations now obtainable…high prices charged by the traders … and loss of most of their stock as a result of the war, they were in distress."[35]

The Commission of inquiry into the Bondelswarts Rebellion later appointed by the South African government stated: "Here we have a people growing each year poorer and yet poorer and more miserable, men and women who require the supreme grace of patience and forbearance just because their conditions of life made them wayward and unreasonable. For such people what was needed and is always needed is the human quality of understanding".[33]

1922 Rebellion

All of these matters came to a head in the autumn of 1922.

The return of Abraham Morris and Sergeant van Niekerk's declaration of war

In April 1922, Abraham Morris, the exiled hero, returned to the Bondelswarts reserve together with fifteen armed companions.[18] No attempt was made to conceal Morris’ arrival in the territory – Jacobus Christian reporting that fact on the same day to Johan Noothout, the superintendent of the reserve.[21] When this was communicated to the magistrate at Warmbad and by him in turn to the Administrator in Windhoek, instructions were issued that Morris and the four men who had crossed the Orange River with him were to be arrested on the technical charge of entering the territory and bringing in stock without the necessary permit and unlawfully introducing firearms into the territory.[21]

Sergeant van Niekerk was sent to Haib in the reserve and on 5 May Morris readily agreed to hand over his rifle, cartridges and Union rifle permit.[33] The sergeant was relieved and offered to pay the nominal fine which he considered would be all the punishment Morris would receive, and left to count the stock which were nearby.[33] The next day the sergeant returned and said that if Morris were willing to go voluntarily to see the magistrate then he would not make the arrest. After discussion it was agreed that Christian would take Morris to Warmbad in a few days’ time.[33] But there was discontent among the Bondelswarts at this agreement, and during the following night Christian and Morris left, but sent a letter to the sergeant saying that although Christian was happy to bring Morris to Warmbad the tribe refused to let him do so.[33] The sergeant then followed Morris to the nearby settlement of Guruchas and tried to arrest Morris, but the crowd of tribesmen would not let him do so.[33] Threatening actions, gestures and words followed and there seems no doubt that Van Niekerk, after calling in vain on some of the Bondelswarts to assist him in the performance of his duty, warned the people that force would be used against them.[33] Native witnesses aver that the phrase used against them was “die lood van die Goevernement sal nou op julle smelt” (the government's lead will now melt upon you").[33] The Bondelswarts took this as a declaration of war. Sergeant Van Niekerk emphatically denied that he had said this.[36] However, Lewis points out that when asked to give evidence Sergeant van Niekerk said that he had lost the pocket book in which he had recorded these events.[36]

According to the report of the Commission of Enquiry later appointed by the South African government, "the turning point in the attitude of the Bondelswarts people was the visit of Sgt van Niekerk – after the events of Sunday 7 May, the whole tone and disposition of the people changed".[33]

Attempted settlement negotiations

On 13 May the Administrator sent the head of the police, Major van Coller, with a strong force to Kalkfontein South (now Karasburg, a small station on the main railway line from South Africa to Windhoek which skirted the reserve.[37] Van Coller sent Jacobus Christian a message through Johan Noothout (the superintendent of the reserve), asking him to meet him to hear an important message from the Administrator. Christian replied: "Dear Sir, I have received your letter and regret that I cannot come to see you and the Administrator. Firstly, my wife and I are sick. Sergeant van Niekerk has told me that I and my people will be destroyed by the Government within a couple of days. This has also been told to me by many witnesses and I am thus expecting to be killed as informed. Further, dear Commissioner, as you have been appointed to look after the interests of the Bondels, we are looking to you and not to the police. So, dear Sir, I am afraid to go to Driehoek and request you come to Haib. Kind regards to all, I am J Christian".[37]

Hofmeyr wanted negotiations to continue, and so on 17 May, Johan Noothout and Monsignor Kolikowski, head of the Catholic mission in the Bondelswarts area, were sent to visit Jacobus Christian.[36] In the negotiations it seems that Noothout exceeded his authority and said that if Morris reported to the magistrate at Warmbad "everything would be forgiven and forgotten and that they would only be tried for being without a pass, and that there would only be an enquiry about the rifles".[36] However, Noothout was not believed and Jacobus Christian asked for confirmation in writing from Hofmeyr. Christian further said that unless such written confirmation was provided the four men would not go to Warmbad because "Sgt. van Niekerk had declared war on them".[36] The written confirmation was not forthcoming, but Hofmeyr offered to meet Jacobus Christian at a place selected by the Administrator.[36] According to Freislich, there is no doubt that the superintendent's behaviour in these negotiations convinced the Bondelswarts that the Administrator was not sincere in his offers to talk with Christian.[37]

On 21 May 1922 the Administrator made further efforts to obtain an amicable settlement by sending Major van Coller to meet Jacobus Christian personally for a discussion of the difficulties.[24] Major van Coller was stopped by sentries who mounted the steps (running-boards) of his car and escorted him in.[24] This was later interpreted by Hofmeyr as a gross insult,[36] and it showed that the Bondelswarts were acting as if a state of war already existed.[36] Van Coller delivered the message that the Administrator demanded the surrender of Morris and four of his companions and of all arms in the Bondelswarts possession, but Christian rejected the demand.[18] Jacobus Christian stated that the Bondelswarts would not surrender their arms and ammunition since the five men had not stolen anything, and Morris had already handed over his rifle to Sgt van Niekerk; besides which the Bondelswarts had no rifles to hand over because the Government had failed to return the rifles handed over by Jacobus in 1919, which he now requested be returned.[36]

An invitation was then extended by the Administrator to Jacobus Christian, to meet him personally at Kalkfontein South, or at some other place outside of the reserve to be agreed.[24] However, Christian would only see the Administrator at Haib, the place where all the Bondelswarts had collected in readiness for the fight.[24] No such meeting ever took place.

Hofmeyr later said that he would have shown leniency if Morris had surrendered and might have given him a suspended sentence.[36] Hofmeyr said he wished for peace, and had tried hard for a peaceful settlement.[36] Whilst this view is supported by the extensive negotiation efforts, on 15 May Hofmeyr had already begun preparations for military action by calling for mounted volunteers and gathering together the government forces.[36] Whether this gathering of troops was intended to increase pressure on the Bondelswarts to make a peaceful settlement is not clear, but it did not have this effect.

The Bondelswarts hastily prepare for war

The Bondelswarts appointed Morris as their military commander and "went into laager" with their women and children in the hills at Guruchas.[18] The Bondelswarts were estimated at 600 men of whom at most 200 were armed.[18] That the Bondelswarts had achieved significant successes against the German forces and that their earlier revolt had helped to spark off a more widespread rebellion may have helped to persuade the Bondelswarts to pit their small and poorly equipped force against the formidable military power of the colonial adversary in 1922.[11] From the state of the Bondelswarts unpreparedness when the first clash with the Government forces came, it seems clear that they had not and were not prepared for revolt, as is shown by their hopelessly inadequate supply of arms and ammunition.[38] To obtain further arms and ammunition, the Bondelswarts planned to ambush government soldiers as they had done in previous campaigns against the Germans, who were inexperienced in bush campaigns. However, the Administration forces contained many who had combat experience in the Anglo-Boer War and were anticipating such tactics.[39]

On 22 May, some Bondelswarts stole six horses from a local farmer, a Mr Becker, and on 23 May they arrived at the farm of a Mr Basson and demanded tobacco, meat, bread and guns and asked Basson's wife to make them some coffee before leaving with three rifles.[36] On 24 May they stole some provisions from the trader at Guruchas, a Mr Viljoen. Then on 25 May they disarmed Noothout (the superintendent of the reserve), and looted his house.[36] Lewis notes that apart from the thefts none of these people were harmed in any way.[36]

The Administration's military build up

The Administrator was justifiably afraid that any prolonged rebellion by the Bondelswarts might stir up widespread guerrilla warfare amongst the tribes which would be on such a scale that it would have to be put down by South African forces.[37]

Hofmeyr arrived at Kalkfontein South on 23 May with his staff and over 100 troops, and this force was augmented over the next two days to a force of 370 mounted riflemen comprising police, civil servants and volunteers from the surrounding districts (farmers and war veterans) – together with two German mountain guns and four Vickers machine guns.[34][24] Hofmeyr felt that delay would be fatal.[36] Although a civilian without military experience, Hofmeyr promoted himself to military rank and took personal command of the armed forces. As the highest-ranking officer in South West Africa was Lt Col. Kruger, Hofmeyr "temporarily" assumed the rank of Colonel.[40] The Windhoek Advertiser poked fun at the self-appointed commander-in-chief: it was possible, the paper held, "that he possessed the military qualities of a Napoleon, but he had reached middle-age without giving proof of his capacities in that direction".[3]

Soon after his arrival, the Administrator surveyed the situation and requested that two aeroplanes be sent up from South Africa.[24] Smuts ordered Colonel Pierre van Ryneveld from Pretoria with two De Havilland DH9 bombers with mounted machine guns.[34] (Van Ryneveld was to later become General Sir Pierre van Ryneveld, chief of staff of the South African army).[39] The DH9 had a capacity to carry around twenty 20-pound (9 kilogramme) Cooper bombs on each flight. Van Ryneveld and his fellow pilots were all decorated air aces of the battles in France, and this was seen as a chance to demonstrate the power of the new air force.[34] The two DH9s arrived at Kalkfontein South on 26 May.[40]

Hofmeyr's plan was to strike quickly before the Bondelswarts revolt spread to the rest of South West Africa and set the whole country ablaze.[40] The crux of the plan was swift action. Hofmeyr stated "if force is needed ... the force used must be so overwhelming and so disposed that the retreat to the Orange River mountains is cut off".[40] The entire Bondelswarts reserve was to be surrounded and the tribesmen were to be driven into Guruchas and forced to surrender.[40]

The initial battles

The first action came at Driehoek in the west of the reserve on 26 May, when one of the government squadrons narrowly avoided a Bondelswarts ambush and drove them off.[40] One government soldier was killed, and nine Bondelswarts were killed, with three wounded and nine prisoners taken.[40] The failure of the ambush was a serious blow to Morris's plans, since the Bondelswarts were very short of arms and ammunition. Instead of fighting along an extended front, they were being forced back into the confines of Guruchas where, mixed up with women, children and stock, they were easy prey.[40]

There was another failed ambush attempt by a group of Bondelswarts under Pienaar in which government forces lost one man, and three men were wounded. However, Pienaar was killed and the Bondelswarts were now in a predicament in that all the waterholes around Guruchas were occupied by government forces,[40] keeping them hemmed in.

The bombing of Guruchas

On 29 May, the government troops, led by Lieutenant Prinsloo who was in operational command of the Administration forces, started to close in on Guruchas.[40] At 3pm the DH9s bombed and strafed the Bondelswarts livestock, causing havoc, wounding seven women and children and killing two children.[24] The Administration and the pilots later claimed that it was not known at the time that there were women and children in the laager.[24]

Prinsloo ordered his ground troops to advance after the initial bombing and strafing and there was a heavy exchange of fire.[39] The Bondelswarts suffered losses but the government troops advanced cautiously, hoping that the impact of their overwhelmingly superior arms and supplies would soon convince the Bondelswarts of the futility of continued resistance.[39] At sunset the planes returned and made another run over the Bondelswart positions. This time bombs were dropped on the ridges south and south-east of the village where the Bondelswarts fire had been the fiercest.[39] But the Bondelswarts fighters were scattered across the hilltops at wide intervals and the bombing achieved very little.[39]

The next morning, the troops returned and burned the Bondelswarts huts to the ground,[20] and the planes swept in again. The people, who were crouched in whatever shelter they could find, heard once more the deafening explosions as the bombs burst one after another amongst the animals.[39] The staccato rattle of their machine-guns could be heard above the engines and amongst the puffs of dust spurting up from the ground ahead of the planes animals pitched to the ground.[39] At this point around ninety men and seven hundred women and children surrendered.[18] Around 150 other fighters had slipped away overnight.

Goldblatt comments that this was the first occasion when aeroplane bombers were used against tribesmen in southern Africa, and it must have struck terror into them.[24] Freislich reports that it was Prinsloo who had first suggested to the Administrator that the bombing should target the flocks of the Bondelswarts, as this would both create havoc and scatter the flocks so that the Bondelswarts would soon run short of food.[39] From Prinsloo's subsequent report, it seems that one of the children killed by the aeroplanes may have been amongst the cattle. Prinsloo states that "I gave instructions that the prisoners had to be guarded and taken to the water and that the body of a native child, which was found lying in amongst some dead cattle, which had evidently been shot by the aeroplanes the previous day, had to be buried by the prisoners."[41]

Brown, writing in the Mail and Guardian in 1998 asserts that the Bondelswarts were more fearful of the machine guns than the aeroplanes. He states "the airmen dropped about 100 bombs and fired several thousand rounds of Vickers machinegun fire. The surrendering Bondels said they didn't mind “as die voel drol kak” ["if the bird dropped bombs"], but in the machine gunning “dans is ons gebars” ["we are done for"].[34] However, according to van Ryneveld's evidence given later, in total sixteen bombs were dropped during the course of the revolt.[40] Brown comments that in this operation there were mixed elements of anger, fear and shame. Anger at Bondelswarts intransigence, fear of another Nama rising that would engulf the whole territory – and shame at the way it had to be done.[34]

Following the fugitives

The 150 men who broke through the cordon on the first day of the bombing were pursued and surrendered a few days later.[18] Morris led the men into Gungunib kloof near the Orange River where he had successfully ambushed a German detachment in 1906 as they searched for water in the dried out waterbed.[34] Morris might have been successful again but two factors were against him. The first is that Prinsloo utilised tactics developed by the Boers in the Boer War, and the second was the reconnaissance power of the aeroplanes.[34]

Prinsloo was able to keep track of the enemy by means of the daylong reconnaissance flights of the aeroplanes, to update the ground troops with this information, and relay messages between the different units of ground troops.[39] According to Prinsloo, the aeroplanes delivered messages in four hours which would have taken an ordinary despatch rider at least 7 or 8 days to deliver (if it was at all possible under the circumstances)."[41] The aeroplanes further demoralised the fugitives by further bombing,[39] and were also able to deliver water, food and provisions to the troops - all of which gave the government forces a great advantage.[39]

As the pursuit went on, the situation of the Bondelswarts became more and more desperate. Every government trooper had a modern rifle with a full bandolier and the reassurance that in due course his ammunition would be replenished.[39] The Bondelswarts, on the other hand, had one rifle to every seven or ten men; they suffered too from the demoralising knowledge that every shot fired brought nearer the moment when they would stand without a single bullet, defenceless.[39]

On 3 June, Prinsloo engaged with the Bondelswarts at a place called Bergkamer. Prinsloo saw the Bondelswarts lying in ambush just in time, and a fierce battle ensued.[40] Government casualties were slight, with a few injuries, but forty-nine of the Bondelswarts were killed, including Morris, and fifteen rifles and all the Bondelswarts remaining cattle and donkeys were captured.[40] On 7 June the exhausted, starving Bondelswarts surrendered, among them Jacobus Christian and other leaders, with 148 others and fifty rifles.[40] In all, around 100 of the Bondelswarts had been killed, with 468 wounded and prisoners; of the administration forces two were killed and four or five wounded.[28]

The able and skilful campaign conducted by Prinsloo had helped to prevent the development of a long and drawn out guerrilla war like that of 1903-1906 which had exacted such a terrible toll on German lives.[40] As experienced guerrilla fighters, the Bondelswarts had in the past been able to hold out for long periods in the mountainous country in the south.[11] The aeroplanes, however, had played a vital role in his success, especially with reconnaissance, in which they had been helped by the fact that the Bondelswarts, who had never seen an aeroplane before in their lives, made no attempt to conceal the smoke from their campfires.[40] Years later, Van Ryneveld, wrote "I remember the picture from the air of the forbidding Gungunib kloof gashing its way through the mountains to the waters of the Orange River … it was easy for us floating above the operation dropping our bombs. We made the canyon reverberate."[34] When the campaign was over, the surviving Bondelswarts leaders had said: “Ons het gedink dit sal soos die Duitse oorlog wees, maar die Boere het orals uitgepeul” (we expected it to be like the German war but the government forces came at us from all sides."[39]

Abuse of prisoners

Many of the Bondelswarts who had surrendered on 30 May at Guruchas reported that although they had put up white flags they had been fired on by the government soldiers, until an officer gave the order to cease fire.[40] Major Herbst, the Secretary for South West Africa and an expert on native affairs, later said that this incident was an accident, and that some children had been shot on the backs of their mothers who were trying to escape from Guruchas.[40] There were also reports of the beating or flogging of Bondelswarts prisoners, and the later investigation noted that proceedings had been taken against those responsible.[40]

Freislich imagines that when it was over, Prinsloo rebuked one of his troopers for his vindictiveness against the Bondelswarts.[39] "We are not here for revenge", Prinsloo said, "but to put an end to this rebellion and that's all". After a short silence a friend of Prinsloo commented, "this isn't pleasant work. These people are fighting for the same thing as we fought the English for twenty years ago: freedom. That's all they want".[39]

Jacobus Christian was tried in the High Court of South West Africa and convicted of engaging in active hostilities against His Majesty's forces.[18] He was defended pro deo by Advocate Israel Goldblatt,[40] who subsequently wrote about the rebellion in his book on the history of South West Africa. The court sentenced Jacobus Christian to five years’ imprisonment with hard labour, but also paid tribute to his character and conduct.[18]

Goldblatt comments in his book that the Bondelswarts, as a consequence of their defeat, were reduced to a miserably poor community.[24] Most of their stock had stampeded across the country and a number had died of thirst. Only about one half of their stock had been returned.[24] However, unlike following other rebellions, the Administration did not impose additional penalties.[24]

The Aftermath

Initial reaction

The ferocity and single-mindedness of the military campaign against the Bondelswarts shocked even the local settler press in South West Africa.[11] An editorial in the Windhoek Advertiser maintained that the "mind revolts at the thought of a bloody campaign against a body of ill-armed savages. The nobler course would have been one of patient perseverance rather than ferocious punishment".[11] Although the newspaper was clearly using the Bondelswarts campaign as a stick with which to beat the Administration in order to further the cause of settler self-government,[11] the criticism is nonetheless pertinent. This is particularly true as the entire Bondelswarts community was made up of fewer than a thousand people (including women and children) of whom no more than 200 were armed.[11]

The Bondelswarts incident was widely reported in South Africa, where the press and members of parliament called for an investigation.[1] Despite widespread criticism, Smuts stood up for the actions of Hofmeyr, and told Parliament in Cape Town: "A great bloodletting has been averted by prompt action".[34]

International reaction was critical. The London Times printed a brief article on the bombing sent by their correspondent in Cape Town within the month, and thereafter newspapers from Ireland to India picked up the story.[20]

Apart from Hofmeyr's use of air power, in Hancock's assessment Hofmeyr had followed the established practice of colonial governments in Africa.[25] Punitive expeditions had been the normal and – so the administrators and soldiers usually maintained – the necessary concomitant of the establishment of European authority.[25] As Hancock comments, if punitive expeditions by the British in Kenya between 1890 and 1910 had been marked on the map, there would have been few, if any, blank spaces except in the desert areas.[25] In fact, this was not the first time bombers had been used to suppress a tribal revolt – in 1920 the Royal Air Force had used bombers against the forces of Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, the "Mad Mullah", in the Somaliland Campaign.[42]

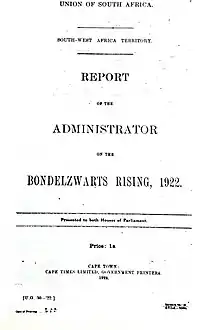

The Administrator's report on the rebellion, June 1922

Very soon after the conclusion of the military action, and before much of the local and international reaction to the overwhelming force used in the suppression of the Bondelswarts, Hofmeyr submitted a report on the Bondelswarts affair to the South African Parliament. The report was issued on 22 June 1922, before it had become clear that a commission of enquiry would be established by the South African government [43] - only on 5 July 1922 did Smuts telegraph Hofmeyr to warn him that pressure for a commission of enquiry was increasing.[43] However, Lewis shows that Smuts nonetheless had input into the writing of the report, and suggested changes to make the report more likely to be acceptable to the Permanent Mandates Commission.[43] Nonetheless, the report is unrepentant and Hofmeyr seems to have had few regrets at this stage.

Hofmeyr's own account of the campaign suggests that the Administration was taken by surprise and that there was an element of panic in its response.[11] On 19 May, during the negotiations before the fighting began, Hofmeyr had received reports of "considerable unrest among the natives" in other areas, and that "some of these were in league with the Bondelswarts and ready to co-operate with them, and that small parties of Hottentots were forcibly collecting arms from isolated farmers in the Warmbad district".[32] He states "in fact, a general panic was once more approaching, and nearly every responsible person believed that a general rising was pending".[32] Hofmeyr states that whilst neither he nor Major Herbst shared this view, "I could no longer delay taking the most expeditious action to re-assure the public as the risk was too great to allow matters to drift".[32] It was only after Hofmeyr's arrival in the south that he received information that convinced him of the "possibility, if not probability, of the whole country going ablaze and the history of German times being repeated unless a peaceful settlement was quickly announced … or a decisive blow was quickly struck.[32]

If the Administration had believed in the possibility of a general rebellion, this would explain why Hofmeyr considered it imperative to strike a "decisive blow"; why it was also thought necessary to bomb the Bondelswarts into submission; and why the Union government was prepared to sanction the use of aircraft so soon after the outcry caused by their employment during the Rand Rebellion.[11] It also makes more comprehensible Hofmeyr's premature announcement after the bombing of Guruchas that the rebellion had been crushed, even although at that stage Morris and a large body of rebels were still at large.[11]

Hofmeyr's attitude to the Bondelswarts is set out clearly in the report: "they are a very warlike and independent race with little respect for the European; so much so that their manner has always been described by Europeans who have come into contact with them as very insolent … to this day they are averse to manual labour".[32] Reflecting on a meeting with the Bondelswarts in 1921, Hofmeyr says "I explained our laws to them, and that it was their duty to assist in the development of the Territory by taking service with the white man."[32]

Hofmeyr felt that Jacobus Christian had deliberately "evaded all possibility of a peaceful settlement" unless Morris and the others were pardoned, and that "the Administration had exercised great patience and, short of going on its knees to the Hottentots, had done everything it was possible to do, in order to avoid bloodshed".[32] Hofmeyr felt that the Bondelswarts grievances like the dog tax, branding law and land disputes were unjustified, and were merely excuses to incite the people and to hide the prevalence of stocktheft.[43]

After the disarming of Noothout by the Bondelswarts on 25 May 1922, Hofmeyr decided that any further delay on his part "would have merited censure".[32] "It was only when I realised the meagreness of my forces in the face of overwhelming difficulties that I reluctantly asked for help from the Air Force".[32] "The use of force was no seeking of mine and I regret that it was necessary, but when once it became clear that there was no alterative I was determined to inflict a severe and lasting lesson".[32]

Hofmeyr's enthusiasm for the action taken during the rebellion were mirrored by a report by Major van Coller, which was annexed to the main report. Major van Coller states that "our superiority was in every instance demonstrated, and it is safe to say that the effect of the lesson taught in this short campaign will leave an indelible impression, not only on the minds of those who resorted to the use of arms in defiance of lawful authority, but on other natives tribes in this territory as well."[32]

Freislich attributes the puzzling aspects of the campaign to the personal failing of Hofmeyr – citing his vanity, ambition and fear of criticism.[11] Emmett comments that although there were signs of panic (initially difficulty was experienced in raising a force for the campaign) and even clearer indications of bungling due to Hofmeyr's lack of military experience, he believes that Freislich's explanation is not a complete nor a convincing one.[11] To Emmett, it seemed improbable that Hofmeyr would have been retained as Administrator until 1926 if his personal failings had been so glaringly obvious, particularly as the suppression of the Bondelswarts rebellion raised an unprecedented international furore.[11]

Increasing pressure in South Africa and Britain

Worried of a coming storm among those who "favour native interests & in League of Nations", Smuts in a letter to Hofmeyr of 5 July 1922 told his old friend not to seize the Bondelswarts’ land (which Hofmeyr had planned to do).[20]

Hofmeyr's report of 22 June 1922 was tabled in the Union parliament by Smuts on 19 July 1922.[43] The following day, under pressure from the South African Parliament, Smuts agreed to an investigation into the affair by the Native Affairs Commission of South Africa.[1] Smuts was already under pressure both as a result of the Rand Revolt of March 1921, where aeroplanes had been used in South Africa to bomb and strafe white miners who were striking in opposition to government proposals to allow non-whites to do more skilled and semi-skilled work previously reserved to whites only, and as a result of the Bulhoek Massacre of 24 May 1921 (which happened almost exactly a year before the Bondelswarts affair). At Bulhoek in the eastern Cape eight hundred South African police and soldiers armed with Maxim machine guns and two field artillery guns killed 163 and wounded 129 members of an indigenous religious sect known as "Israelites" who had been armed with knobkerries, assegais and swords and who had refused to vacate land they regarded as holy to them.[25] Casualties on the government side at Bulhoek amounted to one trooper wounded and one horse killed.[25] Smuts in parliament was immediately on the defensive, and his words might have equally applied to the Bondelswarts affair. "No-one regrets what has happened at Bulhoek more than the Government – and the attitude of the Government all through for months past has been to prevent what has occurred there".[25] Smuts said "I am persuaded in my own mind … that there was no alternative for the police but to fire as they did. I am sure that the Government has done its best to avoid bloodshed, and to make it plain to the people that, whether white or black, they have to submit and obey the law of the land, and the … the law of the land will be carried out in the last resort as fearlessly against black as against white".[25] Hancock comments that Smuts would have done better to have expressed grief at the tragic loss of life.[25] Curiously, in the context of the criticism given of the Bondelswarts affair, the Johannesburg newspaper The Star not only blamed the government for sending too large a force to Bulhoek, but also blamed it for not frightening the Israelites into submission by bombing them from the air.[25] Unlike the Bondelswarts affair, and perhaps because there was no League of Nations supervision, Smuts did not appoint a commission of inquiry into the Bulhoek massacre.[25]

In Britain, then colonial master of South Africa, opinion was initially fairly moderate and restrained. Winston Churchill, as Secretary of State for Colonial Affairs, was questioned about the Bondelswarts incident on 25 July 1922 in the House of Commons.[1] Colonel Wedgwood of the British Labour party raised the Bondelswarts affair in the House of Commons. He wanted to know what steps Britain was taking and questioned the use of aeroplanes to suppress the rebellion. Churchill dismissed the enquiry, saying "I hope we shall find something better to do… than attack our dominions."[43]

First reactions of the League of Nations, September 1922

Shortly after the Bondelswarts affair, South Africa was due to answer questions on its 1921 annual report at the Permanent Mandates Commission. However, South Africa failed to send anyone to appear before the Permanent Mandates Commission, and the Permanent Mandates Commission minutes simply record that the Permanent Mandates Commission would seek information about the rebellion and its repression.[1]

However, when the Assembly of the League of Nations opened in Geneva in September 1922, Dantes Bellegarde of Haiti, one of the very few black delegates in the Assembly, denounced South Africa, saying that the Bondelswarts had been harassed by the government but had not rebelled; nevertheless the administration had sent "all the material of modern warfare – machine-guns, artillery and aeroplanes" against them.[20] "That women and children should have been massacred in the name of the League of Nations and under its protection is an abominable outrage which we cannot suffer" he declared, to prolonged applause.[20] Bellegarde felt that the revolt had been caused by the prohibitive dog tax and intimated that the suppression of the Bondelswarts was a brutal business.[43] The South African representative, Sir Edgar Walton, High Commissioner for South Africa in London, could reply that the incident was under investigation, but the galvanised Assembly agreed that the Permanent Mandates Commission needed to look into the whole sorry situation.[20]

Sir Edgar Walton informed Smuts from Geneva on 16 September 1922 that "the general impression here is, first, that the treatment of this tribe was far from humane; second, that the attack on them was not justified, and third, that the operations were conducted in a brutal manner".[43] Walton continued: "I have assured everybody here that Hofmeyr is one of the most humane men I know, and that anyhow you had ordered a thorough investigation and would certainly see that the enquiry was ample and searching."[43]

According to Hancock, while the Bondelswarts affair was not abnormal for its time, it did receive abnormal publicity - the inevitable consequence of South West Africa's status as a Mandated Territory.[25]

The South African Commission of Enquiry Report, March 1923

The Commission of Enquiry announced by Smuts in the South African Parliament was to be conducted by the Native Affairs Commission of South Africa. The three members of the commission were Senator AW Roberts, Dr CT Loram and General Lemmer. Roberts and Loram had deep roots in the Cape's tradition of tolerance.[25] Roberts by birth was a Scot who had given to South Africa many decades of meritorious service in the fields of Native education and natural science.[25] Loram was South African born, a graduate of Cambridge and Columbia, an educational expert and a pioneer of race relations studies, who in later years achieved a high position at Yale University [25] Loram's doctorate from Columbia was in 1927 published as an influential book.[44] General Lemmer had been a comrade of Botha and Smuts in the Anglo-Boer war and ever since then their faithful follower in politics.[25] Smuts doubtless regarded Lemmer's earthy common sense as a counterweight to the academic sophistication of his two colleagues.[25]

The Commissioners took evidence from 124 witnesses, ranging from the Administrator, other Administration staff, police, military personnel and volunteers involved in the campaign, as well as the chief and other members of the Bondelswarts tribe.[33]

The commission's report was issued on 19 March 1923. The majority (Senator AW Roberts and Dr CG Loram) expressed views critical of the Administration, while General Lemmer dissented in many important respects.[18] In historian Eric Walker's assessment, General Lemmer "a stout old Transvaal general, indeed applauded the Native policy of the Administration, but the other two guardedly censured it".[45] Major Herbst was later to tell the Permanent Mandates Commission that Smuts had described the split nature of the South African Commission of Enquiry on the rebellion as epitomising the "soul of South Africa", since it reflected the deep divisions between Dutch and English-speaking South African's views on native policy.[43]

Lewis comments that from a review of the draft reports in the Roberts’ papers it is clear that Roberts and Loram were initially much more critical of Hofmeyr's role in the rebellion and of his Native Administration generally.[43] However, General Lemmer acted as an effective brake, and his draft report was far more complimentary to Hofmeyr, denying allegations of incompetence or ill-treatment of Bondelswarts prisoners.[43] It was at General Lemmer's insistence that all references to the alleged ill-treatment or shooting of prisoners, the bungling of certain aspects of the military operations by Hofmeyr and in general any severe criticism of the South West African Administration was deleted.[43]

In considering the causes of the rebellion the commission's report focussed on the deep divisions between the administration and the Bondelswarts. The Bondelswarts "considered themselves the equal of white men, and were unwilling to accept the position of a servile race; they had a deep distrust, dating from the time when they first came into contact with the European. This distrust was intensified by the way in which the Europeans' occupation of the land had driven them further and further north to the rocky country in which they now live".[33] The police interviewed had reported that the Bondelswarts were "insolent, lazy and thievish"; the Bondelswarts witnesses regarded the police as "provocative, unnecessarily severe and harsh".[33] The Commission found that while the new Administration had had good intentions, "no adequate effort" had been made "to build up the people under the new conditions of life".[33] It found that there was no real fixed native policy, and said that "if efforts equal to those which were made to facilitate the settlement of Europeans in the land had been made in the case of the indigenous Natives, the latter would have had less cause for complaints".[33]

The Report found that "it is much to be regretted that a meeting between the Administrator and Bondelswarts did not take place, even if it had to be held at Haib, since the Administrator's position would have given weight to such an interview. He could speak with ultimate authority, and he would hear at first the complaints of the men, who, after all, were not an enemy but citizens of the country".[33] However, after this harsh criticism, the Report continued that "when considering the evidence dealing with the period between the visit of van Niekerk and the breaking out of hostilities [it was clear that] that the Administrator wished for peace … and showed patience and forebearance."[33] This was insufficient for General Lemmer, who defended Hofmeyr by saying that Hofmeyr "had done his utmost to bring about such an interview."[33]