Bordentown School

The Bordentown School (officially titled the Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth, the State of New Jersey Manual Training School and Manual Training and Industrial School for Youth, though other names were used over the years) was a residential high school for African-American students, located in Bordentown in Burlington County, New Jersey, United States. Operated for most of the time as a publicly financed co-ed boarding school for African-American children, it was known as the "Tuskegee of the North" for its adoption of many of the educational practices first developed at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.[2] The school closed down in 1955.

New Jersey Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth | |

| |

| |

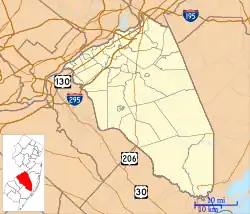

| Location | N of Burlington Rd., W of I-295, Bordentown, New Jersey |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°8′29″N 74°43′25″W |

| Area | 97 acres (39 ha) |

| Built | 1903 |

| Architect | Guilbert and Betelle; Charles N. Lowrie |

| Architectural style | Colonial Revival |

| NRHP reference No. | 97001563[1] |

| Added to NRHP | January 5, 1998 |

Formation and operation

The school was founded in 1886 in the New Brunswick house of the Rev. Walter A. Rice, a minister of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and former slave from Laurens, South Carolina. Born in 1845, Rice had fought as a volunteer with the Union Army during the American Civil War and went to New Jersey to get an education, after completing his military service.[3][4] When it was first founded, it was known as "The Ironsides Normal School".[4] The school's mission was to train African-American students "in such industries as shall enable them to become self-supporting".[5] The state passed legislation in 1894 to designate the school as the state's instructional institution for vocational education. With this legislation, the school was placed under the aegis of a board of trustees composed of state and county officials. The school came under the direct auspices of the New Jersey Board of Education in 1903, with its capital expenditures, curriculum and staffing under state approval.[4] In 1886, the school moved to Bordentown and moved in 1896 to a 400-acre (1.6 km2) tract there that had been owned by United States Navy Admiral Charles Stewart and known as the Parnell Estate.[3][5] The state originally leased the land, and purchased it in 1901.[4]

The school operated on a year-round basis. It had its own farm, cattle, and orchards that supplied the school with its food; scholarship students could work on the farm to cover their tuition. The school was selective and initially offered its 500 to 600 students an education in the Classics and Latin as part of its overall curriculum, which earned accolades from both W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington. Among notable lecturers at the school were Albert Einstein and Paul Robeson.[3] In 1897, James Monroe Gregory became principal at Bordentown. Gregory had been a Latin Professor and Dean at Howard University.[6][7] Gregory served until 1915.[8] In 1913, Booker T. Washington recommended that the school identify occupations prevalent among African-Americans as a guide to developing a curriculum for the school, suggesting that training in automobile repairs for boys would help meet the growing demand for chauffeurs, while girls should be offered "domestic science" training.[9] Students were instructed in a trade in addition to the educational curriculum, with boys instructed in agriculture, auto mechanics, and steam boiler operation, and girls being taught beauty culture, dressmaking, and sewing. During the Great Depression, Bordentown graduates were better able than many to find jobs using the skills they had learned at the school.[10]

Because of financial difficulties, the school accepted state aid and was ultimately taken over by the State of New Jersey in 1897 and placed under the supervision of the New Jersey Department of Education in 1945. William R. Valentine, a graduate of both Columbia University and Harvard University, served as the school's principal from 1915 at least until 1948. Valentine stressed the approach of offering practical job training as a means to prevent students from becoming juvenile delinquents.[11]

Demise and closure

After the passage of the 1947 New Jersey State Constitution, the term "for Colored Youth" was removed from the school's name and it became formally known as the "State of New Jersey Manual Training School" or "Manual Training and Industrial School for Youth" and was opened to students of all races as of 1948.[4][11] In what was called "an example of desegregation in reverse" by The New York Times, Governor of New Jersey Robert B. Meyner ordered that the school be closed in June 1955, citing the school's failure to recruit and retain white students.[12] The closing of the school ended segregation in the state's schools, which had persisted in many South Jersey school districts as late as 1952. In 1956, the site was slated to undergo a conversion to become a school for the developmentally disabled, which was estimated to cost as much as $3 million. The New York Times noted that the facilities were in disrepair, and that some buildings would require extensive repairs, while at least two minor structures were to be demolished.[13] As of 2000, the buildings on the site were being used by the New Jersey Department of Corrections; many of the original buildings were in a dilapidated state.[3]

The school was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1998.[14] It was the subject of David Davidson's 2009 documentary film A Place Out of Time — The Bordentown School, narrated by Ruby Dee and broadcast on PBS in May 2010.[10]

Notable alumni

- Ethel Cuff Black (1890–1977), one of the founders of the Delta Sigma Theta sorority.[15]

- May Edward Chinn (1896–1980), first Black woman to graduate from Bellevue Hospital Medical College.[16]

- Leonard De Paur (1914–1998), composer, choral director and arts administrator.[17]

- George Franklin Grant (1846–1910), inventor of the golf tee.[18]

- George W. Haley (born 1925), former United States Ambassador to The Gambia, and brother of author Alex Haley.[3]

- Maida Springer Kemp (1910–2005), labor organizer who worked extensively in the garment industry[19]

- Rhoda Scott (born 1938), soul jazz organist and singer[20]

Notable faculty

- Alan T. Busby (1895–1992), educator and first African American alumnus of the University of Connecticut.[21]

- Lester Granger (1896–1976), National Urban League leader.[11]

- William H. Hastie (1904–1976), first African-American Governor of the United States Virgin Islands.[11]

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. March 13, 2009.

- Keyes, Allison. "Documentary Focuses On 'Tuskegee Of The North'", National Public Radio, May 24, 2010. Accessed June 8, 2010.

- DeMasters, Karen. "ON THE MAP; Remembering a Boarding School for Black Students", The New York Times, October 1, 2000. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth at Bordentown, NJ: Institutional History, New Jersey Department of State. Accessed November 5, 2016.

- The Bordentown School, Delaware River Heritage Trail. Accessed June 8, 2010.

- Fortune, T. Thomas. After War Times: An African American Childhood in Reconstruction-era Florida. University of Alabama Press, 2014. p97

- School of Great Promise, The New York Age (New York, New York) September 21, 1905, page 2, accessed November 11, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7402868/school_of_great_promise_the_new_york/

- J. M Gregory Out of Bordentown School, The New York Age (New York, New York) February 11, 1915, page 1, accessed November 11, 2016 at https://www.newspapers.com/clip/7403988//

- Staff. "MUST IGNORE POLITICS.; Booker T. Washington Sounds Warning for Bordentown School.", The New York Times, August 12, 1913. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- Jany, Libor. "'A Place Out of Time — The Bordentown School' will air tonight at 10 p.m. on PBS", The Trentonian, May 24, 2010. Accessed June 6, 2010.

- Streator, George. "SCHOOL IN JERSEY AIDS NEGRO YOUTHS; Bordentown 'Exposes' Them to Trades and Skills While Promoting Self-Respect", The New York Times, November 21, 1948. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- Staff. "Jersey to Close All-Negro School Because It Can't Get White Pupils", The New York Times, December 18, 1954. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- Wright, George Cable. "Costs Misfigured On Jersey School; Conversion of Bordentown Negro Institution Calls for More Time and Money", The New York Times, January 5, 1956. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- NEW JERSEY - Burlington County, National Register of Historic Places. Accessed June 6, 2010.

- Boylan, Anne M. "Biographical Sketch of Ethel L. Cuff (Black)", Alexander Street, 2021. Accessed March 7, 2023. "She then enrolled in the Bordentown, New Jersey, Manual Training and Industrial School for Colored Youth as a high school pupil, where she won 'scholarship prizes' and graduated 'with the highest scholastic average.'"

- Davis, George. "A Healing Hand In Harlem", The New York Times, April 22, 1979. Accessed June 3, 2010.

- Woods, Timothy Erickson. Leonard de Paur's arrangements of spirituals, work songs, and African songs as contributions to choral music: A black choral musician in the mid-twentieth century, University of Arizona, 1998. Accessed March 7, 2023. "Leonard de Paur began his music studies at the Manual Training Institute at Bordentown, New Jersey, a military academy and industrial school. He played saxophone and oboe in the band, sang in the glee club, and took theory lessons."

- Taylor, Erica. "Little-Known Black History Fact: The Bordentown School", BlackAmericaWeb.com, May 13, 2010. Accessed June 6, 2010.

- Kelly, Kim. "Maida Springer Kemp Championed Workers’ Rights on a Global Scale", The Nation, December 4, 2022. Accessed March 7, 2023. "Kemp’s life, work, and politics were shaped by her experiences at the intersection of labor, race, gender, class, and colonialism. Her early years in Panama, her childhood in Harlem, her school days at a vocational boarding school in Bordentown, N.J., sometimes called 'The Tuskegee of the North,' and her later international travels all informed her perspective on the world, her place within it, and what kinds of changes were needed."

- "A Cappella Choir, Dance Croup Give Interesting Program At Eastside High",The Morning Call, May 19,1952. Accessed March 7, 2023, via Newspapers.com. "The A Cappella Choir of New Jersey Manual Training School, with the assistance of the modern dance group appeared last night at the Eastside High School auditorium.... Miss Rhoda Scott presided at the piano."

- Roy, Mark J (2001). University of Connecticut. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-0856-6. OCLC 47956317.