Borders of the Roman Empire

The borders of the Roman Empire, which fluctuated throughout the empire's history, were realised as a combination of military roads and linked forts, natural frontiers (most notably the Rhine and Danube rivers) and man-made fortifications which separated the lands of the empire from the countries beyond.

The limes

The word limes is sometimes used by modern scholars to denote the frontier of the Roman Empire but was not used by the Romans as such. After the third century it was an administrative term, indicating a military district, commanded by a dux limitis.[1]

The Latin noun limes had a number of different meanings: a path or balk marking off the boundaries of fields; a boundary line or marker; any road or path; any channel, such as a stream channel; or any distinction or difference between two things.

In Britannia the Empire built two walls one behind the other; for Mauretania there was a single wall with forts on both sides of it. In other places, such as Syria and Arabia Petraea, there was no continuous wall; instead there was a net of border settlements and forts occupied by the Roman army. In Dacia, the limes between the Black Sea and the Danube were a mix of the latter and the wall defenses: the Limes Moesiae was the conjunction of two, and sometimes three, lines of vallum, with a Great Camp and many minor camps spread through the fortifications.

The northern borders

In continental Europe, the borders were generally well defined, usually following the courses of major rivers such as the Rhine and the Danube. Nevertheless, those were not always the final border lines; the province of Dacia, modern Romania, was completely on the far side of the Danube, and the province of Germania Magna, which must not be confused with Germania Inferior and Germania Superior, was the land between the Rhine, the Danube and the Elbe (Although this province was lost three years after its creation as a result of the Battle of Teutoburg Forest).

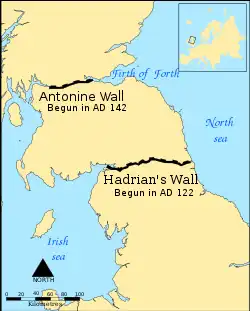

In Great Britain both Hadrian and Antoninus Pius built defences to protect the province of Britannia from the Caledonians. Hadrian's Wall, constructed in 122 held a garrison of 10,000 soldiers, while the Antonine Wall, constructed between 142 and 144, was abandoned by 164 and briefly reoccupied in 208, under the reign of Septimius Severus.

The Pannonian Limes

The eastern borders

The eastern borders changed many times, as the Roman Empire was facing two major powers, The Parthian Empire and the Sasanian Empire. The Parthians were a group of Iranian peoples ruling most of Greater Iran that is in modern-day Iran, western Iraq, Armenia and the Caucasus.[2] The Sasanians succeeded the Parthians in 224–226 and were recognised as one of the leading world powers alongside its neighbouring arch-rival the Roman (Byzantine) Empire for a period of more than 400 years.

The southern borders

At the greatest extent of the Empire, the southern border lay along the deserts of Arabia in the Middle East and the Sahara in North Africa, which represented a natural barrier against expansion. The Empire controlled the Mediterranean shores and the mountain ranges further inland. The Romans attempted twice to occupy the Siwa Oasis and finally used Siwa as a place of banishment. However, the Romans controlled the Nile many kilometres into Africa up to Syena, Berenice, Hyerasykaminos and even Qasr Ibrim, (the southernmost of all), near the modern border between Egypt and Sudan, then Meroe, lying very near the tropic. The period in which each aforementioned town represented the final frontier of Rome is uncertain.

In Africa the Romans controlled the area north of the Sahara, from the Atlantic Ocean to Egypt, with the borders being controlled by many sections of fortifications such as the Limes Arabicus (called the Limes Uranus), Limes Mauretaniae, Fossatum Africae, Fossa regia, Limes Tripolitanus, Limes Numidiae, etc.[3]

In the south of Mauritania Tingitana Romans made a limes in the third century, just north of the area of actual Casablanca near Sala and stretching to Volubilis.

Septimius Severus expanded the "Limes Tripolitanus" dramatically, even briefly holding a military presence in the Garamantian capital Garama in AD 203. Much of the initial campaigning success was achieved by Quintus Anicius Faustus, the legate of Legio III Augusta.

Following his African conquests, the Roman Empire may have reached its greatest extent during the reign of Septimius Severus,[4][5] under whom the empire encompassed an area of 5 million square kilometres (2 million square miles).[4]

References

- Benjamin Isaac, "The Meaning of 'Limes' and 'Limitanei' in Ancient Sources", Journal of Roman Studies, 78 (1988), pp. 125–147

- Benjamin Isaac, The Limits of Empire: the Roman Army in the East (Oxford University Press, revised ed. 1992)

- "Map of Roman Africa". www.gutenberg.org.

- David L. Kennedy, Derrick Riley (2012), Rome's Desert Frontiers, page 13, Routledge

- R.J. van der Spek, Lukas De Blois (2008), An Introduction to the Ancient World, page 272, Routledge

Bibliography

- De Agostini (2005). Atlante Storico De Agostini. Novara: Istituto Geografico De Agostini. ISBN 88-511-0846-3.

- Camer, Augusto and Renato Fabietti. Corso di storia antica e medievale 1 (seconda edizione). ISBN 88-08-24230-7.

- Grant, Michael (1994). Atlas of Classical History (5th ed.). New York: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 0-19-521074-3.

- Scarre, Chris (1995). The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Rome. London: Penguin. ISBN 0-14-051329-9.

Further reading

| Library resources about Borders of the Roman Empire |

- Breeze, David J. 2011. The Frontiers of Imperial Rome. Barnsley, UK: Pen & Sword.

- Cordovana, Orietta Dora. 2012. "Historical Ecosystems. Roman Frontier and Economic Hinterlands in North Africa." Historia 61.4: 458-494.

- Dyson, Stephen. 1985. The Creation of the Roman Frontier. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press.

- Gambash, Gil. 2015. Rome and Provincial Resistance. London: Routledge.

- Heckster, Olivier, and Ted Kaizer, eds. 2011. Frontiers in the Roman World: Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop of the International Network Impact of Empire. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

- Hingley, Richard. 2012. Hadrian’s Wall: A Life. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Isaac, Benjamin. 2000. The Limits of Empire: The Roman Army in the East. Rev. ed. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

- Keppie, Lawrence. 2012. The Antiquarian Rediscovery of the Antonine Wall. Edinburgh: Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

- Sterk, Andrea. 2010. "Mission from Below: Captive Women and Conversion on the East Roman Frontier." Church History 79.1:1-39.

- Zietsman, J.C. 2009. "Crossing the Roman frontier: Egypt in Rome (and beyond)." Acta Classica 52: 1-21.