Sands of Beirut

The Sands of Beirut were a series of archaeological sites located on the coastline south of Beirut in Lebanon.[2]

Shown within Lebanon | |

| Location | coastline south of Beirut, Lebanon |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 33.886944°N 35.513056°E |

| Type | series of sites |

| History | |

| Periods | Paleolithic, Kebaran, Natufian, Khiamian, Neolithic, Chalcolithic |

| Site notes | |

| Excavation dates | 1965 |

| Archaeologists | J.W. Chester J. Dawson G. Zumoffen Henri Fleisch N. Josserand Abbe Remonney[1] Lorraine Copeland Peter Wescombe |

| Condition | ruins |

| Public access | Yes |

Description

The Sands were a complex of nearly 20 prehistoric sites that were destroyed due to building operations using the soft sandstone in constructing the city of Beirut and Beirut Airport.[3] The large number of open air sites provided a wealth of flint relics from various periods including Natufian remains, unstratified but suggested to date between c. 10000 BC to c 8000 BC. Finds included sickles used for harvesting wild cereals as just prior to the agricultural revolution.[4] The transition into the neolithic is well documented with Khiamian sites also being represented in the Sands.[5] Evidence of pre-Natufian Kebaran occupation was also found.[6]

The materials recovered are now held by the Museum of Lebanese Prehistory part of the Saint Joseph University.[7] It is one of the few sites showing signs of real village occupation in the late pleistocene.[8] The first flints were found by J. Chester and further studies by J.W. Dawson were published in 1874. This was followed by extensive research by Father G. Zumoffen who published in 1893.[9] Henri Fleisch also catalogued and recovered materials from the sites in the 1960s, the destruction of the Sands of Beirut was recently exhibited through Father Fleisch's photography in June 2010 at the Museum of Lebanese Prehistory.[3]

Sands of Beirut archaeological sites included:

| Sands site | Copeland and Wescombe number | Fleisch number |

| Bir Hassan | 1 | 15 |

| Borj Barajne | 2 | 9 |

| Khan Khalde | 3.A. and 3.B. | 1 and 2 |

| Mar Elias (Saint Elie) | 4.A. | 17 |

| Mar Elias El Tiffeh | 4.B. | 17 |

| Nahr Ghedir | 5 | 4 |

| Ouza'i | 6.A. | 13 |

| Ouza'i | 6.B. | 14 |

| Tell Arslan | 7 | 3 |

| Tell aux Scies | 8 | 16 |

| Site 5 (Shell Station) | 9 | 5 |

| Site 6 (north of Shell Station) | 10 | 6 |

| Site 7 (Airport Boulevard) | 11 | 7 |

| Site 8 (southwest of Ain Sekka) | 12 | 8 |

| Site 10 (Mdaoura) | 13 | 10 |

| Site 11 (Haret Hraik) | 14 | 11 |

| Site 12 and extension | 15.A. and 15.B. | 12 |

| The Stone Circles | 16 | - |

| Khan El Asis | 17 | - |

Bir Hassan

This site was located at the top of the Bir Hassan dune at approximately fifty five meters above sea level extending down the slopes towards Ouza'i. Thousands of flint tools were collected from the site from various periods. It was first published as Lower Paleolithic and Middle Paleolithic by Auguste Bergy in 1932 and as Middle and Upper Paleolithic by Henri Fleisch in 1965.[10][11] Some of the material was found at a depth of three and a half meters below the sands. A trace of Neolithic was found along with three Emireh points and a series of styled picks that were given their name from this site, known as Bir Hassan picks.[12][13]

Borj Barajne

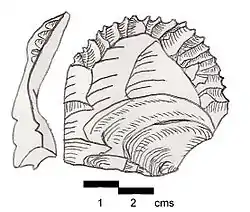

Also called Tell aux Crochets, Tell Mouterde or Cote 52, it is now built over by a refugee village.[14] Finds from this site were recovered by Jesuits and included flint arrowheads and geometric Mesolithic tools.[15] It was first discovered by Father René Mouterde and material was published by Godefroy Zumoffen in 1910, Auguste Bergy in 1932 and Henri Fleisch in 1956 and 1965.[10][11][13][16] Microliths were found along with trapezoid and crescent arrowheads of the Natufian variety with tangs and notches along with Helwan points. Also found were a Ksar Akil flake, Emireh points and traces of a Neolithic settlement.[12] A Ksar Akil flake (pictured) was found here.

Khan Khalde

There are two sites at Khan Khalde, 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south of Beirut around the Khalde station. Site 1 or 3.A. is located west of the station buildings and contained mostly Middle Paleolithic material with traces of Mesolithic and Neolithic along with one Emireh point. Site 2 or 3.B. is a section in the railway cutting where material studies by Fathers Fleisch and Ramonnay determined to be largely Levalloiso-Mousterian with some Upper Paleolithic and Neolithic traces. They were found by Auguste Bergy, published by Henri Fleisch in 1965 and kept in the Museum of Lebanese Prehistory.[11]

Mar Elias (or St. Elie) and Mar Elias el Tiffeh

These sites were discovered by either Paul Bovier-Lapierre or Chester. One is 400 metres (1,300 ft) northwest of the monastery of St. Elie, now in the UNESCO building complex, another is in the area of Rue Ittifek and another was in the extension south of the monastery.[2] A Mesolithic industry was found along with a Levallois one by Bergy in 1932.[10] Material was mentioned by Fleisch in 1965, who considered it Levalloiso-Mousterian with a few pieces from the Neolithic.[11]

Nahr Ghedir

This site is on the right bank at the old mouth of the Nahr Ghedir. Material including an Emireh point, large quantities of Middle Paleolithic tools, a few Upper Paleolithic and a trace of Neolithic were discussed by Fleisch in 1965.[11]

Ouza'i (Neba el Auza'i)

This site is 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) south of Beirut also on the east of the road to Sidon and is around 600 metres (2,000 ft) by 250 metres (820 ft) in the dunes at the start of the Khalde Boulevard, east of the mosque. It was mentioned by Godefroy Zumoffen in 1900 and Henri Fleisch in 1956.[13][17] Material from the site was considered largely similar to that of the Néolithique Récent of Byblos by Jacques Cauvin including long, narrow adzes, chisels, segmented sickle blades with fine denticulation, borers and a transverse arrowhead found by Auguste Bergy about 750 metres (2,460 ft) east of the minaret.[12]

Site 6

This site is north of Shell petrol station, 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) south of Beirut near the Airport terminal. Some flints similar to the Neolithique Moyen period of Byblos were found at this site alongside Palaeolithic material.[11][18]

Site 7

A semi-circular site northeast of the Shell petrol station continuing to a point underneath Airport Boulevard. It was discovered by August Bergy and Henri Fleisch with collections made by P.E. Gigues of a non-geometric Mesolithic industry along with numerous core scrapers and two Emireh points.[10][11] The site has now been destroyed but material is stored in the Museum of Lebanese Prehistory.[12]

Site 8

Another Mesolithic site located a few meters north of Site 7 with tools from a similar industry but with no Neolithic material.[11]

Site 10

Mdaoura or Tell aux Haches, 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) south of Beirut on the east of the road to Sidon, inland from the coast near Mdaoura. A small site containing two Emireh points, a Natufian arrowhead and a number of axes from various periods including the Neolithic.[11]

Site 11

Also known as Haret Hraik and located about 40 metres (130 ft) east of Ouza'i at around 40 metres (130 ft) above sea level, this site contained only Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic material. It disappeared underneath a refugee camp in 1950.[11]

Site 12

This site is east of the Zone Militaire on the top of a dune above a wood to the west of the first circle of Airport Boulevard, near Bir Hassan. Middle and Upper Paleolithic forms were found with traces of Neolithic material. The site disappeared in 1954.[11]

The Stone Circles

A site where stone circle structures were found by Lorraine Copeland and Peter Wescombe.[14] They were located at the east end of the runway of Beirut Airport covering a site of approximately 500 square metres (0.050 ha). Preliminary excavations were carried out by M.R. Saidah in 1964. The site contained two areas, one of red sand where human burials were discovered and another of modern sand where six stone circles were observed in 1964 around 20 metres (66 ft) to 40 metres (130 ft) from the runway, these were bulldozed in 1965 to make a golf course, leaving only one standing. The circles were composed of large river boulders, varying in diameters between 8 metres (26 ft) and 15 metres (49 ft). A nearby ramleh outcrop contains a large, square empty cistern or well cut into the sandstone. Flints including Levallois cores, flakes and waste were dispersed across the whole area but gave little evidence regarding the age of the stone circles.[12]

Tell Arslan

Tell Arslan was a more substantial archaeological site in the Sands of Beirut than the open air surface stations, with a full tell mound covering 1 hectare (10,000 m2) situated 8.5 kilometres (5.3 mi) south of Beirut and about 800 m east of the beach. It was first excavated by Father Auguste Bergy in 1930. It represents the earliest known neolithic village settlement in the Beirut area.[19] Henri Fleisch also recovered more material during a rescue mission in 1948 when the site was levelled due to construction of Beirut airport. All this material is now in the Saint Joseph University, Museum of Lebanese Prehistory. The site shows evidence of also having been occupied during the Roman era. Pottery and flints were recovered including a variety of axes, knives, chisels, scrapers, borers, and picks. Sickle blades were mostly finely serrated or showed coarse denticulation. Pottery was hardened by firing and included flat bases, a strap handle and a few sherds incised with stab marks and parallel lines. Jacques Cauvin concluded the artefacts similar and the site likely contemporary with middle neolithic periods of Byblos. A.M.T. Moore argued that finds such as Amuq points and short axes were more archaic still, possibly even dating into the Upper Paleolithic. He further suggested the site had been frequented by hunter-gatherer groups forming temporary camps and developed into a village during the early neolithic period.[20]

Tell aux Scies

Tell aux Scies or Tell of Saws is located south of Beirut, in the dunes near the coast. Father Auguste Bergy collected PPNB materials from the site in 1932 before it was turned into landfill for rubbish.[21] The large and notable assemblage from the site included a set of nibbled or finely denticulated sickle blades from which the site takes its name.[21] Also recovered were crested blades, two distinct types of arrowhead, awls, scrapers, polished axes, scissors, chisels, borers, scrapers, retouched blades, microburins and a few flaked picks. Jacques Cauvin has termed the collection of flints from this site as a "nucléus naviformes", which he claimed may represent an older type of lithic technology than found in the most archaic neolithic levels from Byblos.[7][22][23] The site has shown many similarities to Damascus basin sites and compared to the very earliest levels of Tell Ramad, dating to the earliest stage of the PPNB.[21]

References

- Jean Perrot (2001). Paléorient: revue pluridisciplinaire de Préhistoire et Protohistoire de l'Asie du Sud-Ouest. CNRS Editions. ISBN 978-2-271-05789-1. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Université Saint-Joseph (Beirut; Lebanon) (1966). Mélanges de l'Université Saint-Joseph pp. 59, 169 & 172. Impr. catholique. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Sfeir, Mia., Femme Magazine - Préhistoire VS Urbanisation, le témoignage d’Henri Fleisch - Issue 206 - P.70 Published June 1, 2010 Archived September 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Samir Kassir; Malcolm Debevoise; Robert Fisk (15 November 2010). Beirut, p. 33. University of California Press. pp. 33–. ISBN 978-0-520-25668-2. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Fuller, Dorian Q., Origins of Agriculture: General Introduction and the Near East, p. 4, Institute of Archaeology UCL

- American University of Beirut. Museum of Archaeology (1971). Berytus: archeological studies. The American University of Beirut. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Jacques Cauvin; Trevor Watkins (2000). The birth of the Gods and the origins of agriculture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-521-65135-6. Retrieved 25 April 2011.

- John L. Bintliff; Willem van Zeist, eds. (1982). Palaeoclimates, palaeoenvironments and human communities in the Eastern Mediterranean region in later prehistory. B.A.R. ISBN 978-0-86054-164-6. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- L'Anthropologie, p. 2. Masson. 1914. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Bergy, Auguste., La paléolithique ancien stratifié à Ras Beyrouth, pp.200-202, Mélanges de l'Université Saint Joseph, Volume 16, 5-6, 1932.

- Fleisch, Henri., Les sables de Beyrouth et leurs industries préhistoriques, Festschrift for A. Rust's 65th Anniversary, Cologne University, 2nd Series, 1965.

- Lorraine Copeland; P. Wescombe (1965). Inventory of Stone-Age sites in Lebanon, p. 128-135. Imprimerie Catholique. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Fleisch, Henri., Depôts préhistoriques de la Côte libanaise et leur place dans la chronologie basée sur le Quaternaire Marin, Quaternaria, Volume 3, p. 111, note 12 and p. 116, note 17, 1956.

- Ofer Bar-Yosef; François Raymond Valla (1991). The Natufian culture in the Levant pp. 33-35. International Monographs in Prehistory. ISBN 978-1-879621-03-9. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Salwa C. Nassar Foundation for Lebanese Studies (1970). Beirut--crossroads of cultures. Librairie du Liban. Retrieved 4 April 2011.

- Zumoffen, Godefroy., Le Néolithique en Phénicie, Anthropos, Volume 5, p. 143. 1910.

- Godefroy Zumoffen (1900). La Phénicie avant les phéniciens: l'âge de la pierre. Impr. catholique. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. pp. 428–433.

- Nina Jidejian (1973). Beirut through the ages, p. 14. Dar el-Machreq [distribution: Librairie orientale. Retrieved 5 April 2011.

- Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. pp. 425–427.

- Moore, A.M.T. (1978). The Neolithic of the Levant. Oxford University, Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis. pp. 205–207.

- Cauvin, J., Les outillages néolithiques de Byblos et du littoral libanais. Fouilles de Byblos, tome IV, Paris, Librairie d’Amérique et d’Orient, J. Maisonneuve, 1968, p. 228.

- Association Paléorient (2006). Paléorient, p. 58. Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. ISBN 978-2-271-06451-6. Retrieved 25 April 2011.