Born alive laws in the United States

Born alive laws in the United States are fetal rights laws that extend various criminal laws, such as homicide and assault, to cover unlawful death or other harm done to a fetus in uterus or to an infant that is no longer being carried in pregnancy and exists outside of its mother. The basis for such laws stems from advances in medical science and social perception, which allow a fetus to be seen and medically treated as an individual in the womb and perceived socially as a person, for some or all of the pregnancy.

Such laws overturn the common law legal principle that until physically born, a fetus or unborn child does not have independent legal existence and therefore cannot be the victim of such crimes. They often provide for transferred intent, sometimes called "transferred malice", so that an unlawful act which happens to affect a pregnant woman and thus harm her fetus can be charged as a crime with the fetus as a victim, in addition to crimes against any other people.

History of born alive law

Common law

The born alive rule was originally a principle at common law in England that was carried to the United States and other former colonies of the British Empire. First formulated by William Staunford, it was later set down by Edward Coke in his Institutes of the Laws of England: "If a woman be quick with childe, and by a potion or otherwise killeth it in her wombe, or if a man beat her, whereby the child dyeth in her body, and she is delivered of a dead childe, this is great misprision, and no murder; but if he childe be born alive and dyeth of the potion, battery, or other cause, this is murder; for in law it is accounted a reasonable creature, in rerum natura, when it is born alive."[1]

The phrase "a reasonable creature, in rerum natura" as a whole is usually translated as "a life in being", i.e. where the umbilical cord has been severed and the baby has a life independently of the mother.[2] "Reasonable" here is used as in the 16th century, meaning "something that may reasonably be considered [a living creature]". In English law this meant that until born, the fetus was not accounted a person under criminal law, nor a separate person from its mother, and could not have the capacity to be the subject of an actus reus ('wrongful act') – a prerequisite for a criminal offense in the absence of any statute to the contrary.

Subsequent developments

In the 19th century, some began to argue for legal recognition of the moment of conception as the beginning of a human being, basing their argument on growing awareness of the processes of pregnancy and fetal development.[3][4] They succeeded in drafting laws which criminalized abortion in all forms and made it punishable in secular courts. Advances in the state of the art in medical science, including medical knowledge related to the viability of the fetus, and the ease with which the fetus can be observed in the womb as a living being, treated clinically as a human being, and (by certain stages) demonstrate neural and other processes considered as human, have led a number of jurisdictions – in particular in the United States – to supplant or abolish this common law principle.[3]

Changes to the law proceed piecemeal, from case to case and from statute to statute, rather than wholesale. One such landmark case with respect to the rule was Commonwealth vs. Cass, in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, where the court held that the stillbirth of an eight-month-old fetus, whose mother had been injured by a motorist, constituted vehicular homicide. By a majority decision, the Supreme Court of Massachusetts held that a viable fetus constituted a "person" for the purposes of vehicular homicide law. In the opinion of the justices, "We think that the better rule is that infliction of perinatal injuries resulting in the death of a viable fetus, before or after it is born, is homicide."[5]

Several courts have held that it is not their function to revise statute law by abolishing the born alive rule, and have stated that such changes in the law should come from the legislature. In 1970 in Keeler v. Superior Court of Amador County, the California Supreme Court dismissed a murder indictment against a man who had caused the stillbirth of the child of his estranged pregnant wife, stating that "the courts cannot go so far as to create an offense by enlarging a statute, by inserting or deleting words, or by giving the terms used false or unusual meanings ... Whether to extend liability for murder in California is a determination solely within the province of the Legislature."[6]

Several legislatures passed laws to explicitly include deaths and injuries to fetuses in utero. The general policy has been that an attacker who causes the stillbirth of a fetus should be punished for the destruction of that fetus in the same way as an attacker who attacks a person and causes their death. Some legislatures have simply expanded their existing offences to explicitly include fetuses in utero. Others have created wholly new, and separate, offences.[5]

Federal laws

The Born-Alive Infants Protection Act ("BAIPA" Pub. L.Tooltip Public Law (United States) 107–207 (text) (PDF), 116 Stat. 926, enacted August 5, 2002, 1 U.S.C. § 8) extends legal protection to an infant born alive after a failed attempt at induced abortion. It passed into law on August 5, 2002.[7] The law defines a "born alive" infant as the complete expulsion of an infant at any stage of development that has a heartbeat, pulsation of the umbilical cord, breath, or voluntary muscle movement, regardless of circumstances of birth or severance of the umbilical cord, and provides rights for such infants. The Born-Alive Abortion Survivors Protection Act is a proposed law that would provide criminal penalties to any practitioner who denies a born-alive infant medical care.

The Unborn Victims of Violence Act (Public Law 108-212) recognizes a "child in utero" as a legal victim, if he or she is injured or killed during the commission of any of over 60 listed federal crimes of violence. The law defines "child in utero" as "a member of the species Homo sapiens, at any stage of development, who is carried in the womb".[8] It applies only to certain offenses over which the United States government has jurisdiction, including certain crimes committed on federal properties, against certain federal officials and employees, and by members of the military, as well as certain crimes (including some acts of terrorism) which count as federal offenses even if outside the United States. The act explicitly provides that it may not "be construed to permit the prosecution" of any person in relation to consensual abortion, medical treatment of a mother or her fetus, or any woman with regard to her own fetus. It passed into law on April 1, 2004 and is codified under two sections of the United States Code: Title 18, Chapter 1 (Crimes), §1841 (18 USC 1841), and the Uniform Code of Military Justice: Title 10, Chapter 22 §919a (Article 119a). The law was both hailed and vilified by legal observers who interpreted the measure as a step toward granting legal personhood to human fetuses.

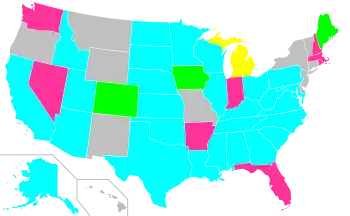

List of laws by state

California

§187 of the California Penal Code was amended to redefine murder to include the unlawful killing of a fetus. The term "fetus" was not initially defined.

In People v. Smith (1976)[9] the court qualified this as signifying a viable fetus, holding that until the capability for independent existence is attained by a fetus "there is only the expectancy and potentiality for human life". They reasoned that the U.S. Supreme Court had implicitly stated in various cases dealing with abortion, that destruction of a nonviable fetus did not constitute taking a human life. As homicide was the unlawful destruction of a human life, proof was required that the unlawful destruction of a human life had in fact occurred. Thus it was held that the defendant was guilty of abortion, but not homicide.[5]

In People v. Davis (1994), the California Supreme Court examined this and concluded fetal viability was not essential for rights to exist. They reasoned that abortion cases such as Wade v. Roe discuss where to draw the line for legitimate state interest in situations where the interests of fetus and mother conflict. Such cases do not discuss, and do not preclude, a legitimate state interest in protecting the potentiality of human life perhaps arising at a different time in situations where the rights of the fetus do not have to be set against the rights of the mother.

Minnesota

Vehicular homicide, death to an unborn child, and injury to an unborn child are three separate offences, under the umbrella of criminal vehicular operation.[10]

References

- Cited in "The New "Fetal Protection": The Wrong Answer to the Crisis of Inadequate Health Care for Women and Children" Archived 2011-07-20 at the Wayback Machine, Linda Fentiman, 2006, note 119, (abstract and download link)

- Attorney General's Reference No 3 of 1994 Attorney General's Reference No 3 of 1994 [1997] UKHL 31, [1998] 1 Cr App Rep 91, [1997] 3 All ER 936, [1997] 3 WLR 421, [1997] Crim LR 829, [1998] AC 245 (24 July 1997), House of Lords

- Sheena Meredith (2005). Policing Pregnancy: The Law And Ethics of Obstetric Conflict. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 182. ISBN 0-7546-4412-X.

- William M. Connolly (2002). One Life: How the U.S. Supreme Court Deliberately Distorted the History, Science and Law of Abortion. Xlibris Corporation. ISBN 1-4010-3786-0.

- John (John A.) Seymour (2000). Childbirth and the Law. Oxford University Press. pp. 140–143. ISBN 0-19-826468-2.

- David C. Brody; James R. Acker; Wayne A. Logan (2001). "Criminal Homicide". Criminal Law. Jones and Bartlett. p. 411. ISBN 0-8342-1083-5.

- "Born-Alive Infants Protection Act of 2002 (2002 - H.R. 2175)".

- Archived 2012-01-06 at the Wayback Machine Text of Unborn Victims of Violence Act.

- 129 Cal. Rptr. 498 (Ct. App. 1976).

- James Cleary & Joseph Cox. "A Brief Overview of Minnesota's DWI Laws: Minnesota Statutes Chapter 169A and Related Laws" (PDF). Minnesota Impaired Driving Facts Report. Minnesota Department of Public Safety. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-09-26. Retrieved 2012-01-06.