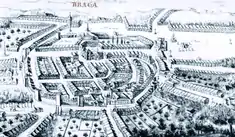

Braga

Braga (/ˈbrɑːɡə/ BRAH-gə, Portuguese: [ˈbɾaɣɐ] ⓘ; Proto-Celtic: *Bracara) is a city and a municipality, capital of the northwestern Portuguese district of Braga and of the historical and cultural Minho Province. Braga Municipality had a resident population of 193,333 inhabitants (in 2021),[1] representing the seventh largest municipality in Portugal by population. Its area is 183.40 km2.[2] Its agglomerated urban area extends to the Cávado River and is the third most populated urban area in Portugal, behind Lisbon and Porto Metropolitan Areas.

Braga | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) _(cropped).jpg.webp) .jpg.webp) _(cropped).jpg.webp) _(cropped).jpg.webp)  .jpg.webp) Top: Banco de Portugal; Sameiro Sanctuary; middle: Congregados Church; Bom Jesus do Monte; Tibães Monastery; bottom: Arco da Porta Nova; Braga Episcopal Palace. | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| |

| Coordinates: 41°33′4″N 8°25′42″W | |

| Country | |

| Region | Norte |

| Intermunic. comm. | Cávado |

| District | Braga |

| Parishes | 37, see text |

| Government | |

| • President | Ricardo Rio (PSD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 183.40 km2 (70.81 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 200 m (700 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 558 m (1,831 ft) |

| Population (2021) | |

| • Total | 193,333 |

| • Density | 1,100/km2 (2,700/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC±00:00 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+01:00 (WEST) |

| Postal code | 470x |

| Area code | 253 |

| Website | www |

It is host to the oldest Portuguese archdiocese, the Archdiocese of Braga of the Catholic Church and it is the seat of the Primacy of the Spains. During the Roman Empire, then known as Bracara Augusta, the settlement was the capital of the province of Gallaecia and later of the Kingdom of the Suebi that was one of the first to separate from the Roman Empire. Inside of the city there is also a castle tower that can be visited. Nowadays, Braga is a major hub for inland Northern Portugal and it is an important stop on the Portuguese Way path of the Road of St James. The city was also the European Youth Capital in 2012.[3]

History

.JPG.webp)

Pre-Roman

Human occupation of the region of Braga dates back thousands of years, documented by vestiges of monumental structures starting in the Megalithic era. During the Iron Age, the Castro culture extended into the northwest, characterized by Bracari peoples who occupied the high ground in strategically located fortified settlements (castrum).

The region became the domain of the Callaici Bracarii, a Celtic[4] tribe who occupied what is now northern Portugal, Galicia and Asturias in the northwest of Iberia.

Roman rule

The Romans began their conquest of the region around 136 BC, and finished it, by conquering the northern regions, during the reign of Emperor Augustus. The civitas of Bracara Augusta was founded in 16 BC; in the context of the administrative reorganization of these Roman acquisitions, Bracara was rededicated to the Emperor taking on the name Bracara Augusta. The city of Bracara Augusta developed greatly during the 1st century and reached its maximum extension around the 2nd century.

Towards the end of the 3rd century, the Emperor Diocletian promoted the city to the status of capital of the administrative area Conventus bracarensis, the southwestern area of the newly founded Roman province of Gallaecia.

Braga in Late Antiquity and Middle Ages

The city was described as prosperous by the poet Ausonius, in the 4th century.[5] Between 402 and 470 the Germanic Invasions of the Iberian Peninsula occurred, and the area was conquered by the Suebi, a Germanic people from Central Europe. According to records the city was protected by a wall, still in use since the 3rd century, and the old Roman amphitheatre was repurposed into a fortress.[5] In 410, the Suebi established a Kingdom in northwest Iberia covering what is present-day's Northern half of Portugal,[6] Galicia and Asturias, which they maintained as Gallaecia, and had Bracara as their capital. This kingdom was founded by Hermeric and lasted for over 150 years. However, the departure of the Vandals and the arrival of the Visigoths brought a new instability to the region. Between 419 and 422, Braga was threatened by the Vandals so it prepared itself for a siege, closed its gates and refused to open them; this led to the destruction of the surrounding countryside.[5] Nevertheless, between 429 and 455, the Suebi made a military comeback in Iberia reinforcing their hold in Galeicia and Lusitania.[5] In 455, while the Visigothic king Theodoric II sacked Braga, utterly destroying many historical and archaeological records,[5] the Suebi king Rechiar escaped the city, wounded, to Porto.[7] However, records of a list of dioceses and parishes of Braga, made in 570 still exist.[5] By about 584, the Visigoths took permanent control of Gallaecia from the Suebi, and Braga was made a provincial capital.

Because historians are still unsure of the dating of the Chapel of São Pedro de Balsemão, in Lamego, currently Braga hosts the oldest chapel in Portugal, the Chapel of São Frutuoso. The chapel was built by the Visigoths on top of a Roman temple to Asclepius and it was made to be a Royal Chapel. In 656 AD, it was consecrated by Saint Fructuosus[5] to be used as his tomb.

Historical records show, so far, that the first known bishop of Braga was named Paternus,[5] who famously renounced priscillianism at the First Council of Toledo, in September of 400 AD. We also have records of a bishop named Balconius (415-447), who was also recorded to be present when the Iberian clergy received, in 435, a German priest from Arabia accompanied by several Greeks with news from the Council of Ephesus (431).[5] Balconius was also a contemporary and correspondent of Pope Leo I.[5]

Tradition, however, states that Saint Peter of Rates was the first bishop of Braga, a Jew personally elevated to the role by Saint James. Another bishop, Saint Ovidius (d. 135 AD) is also sometimes considered one of the first bishops of this city.

Braga had an important role in the Christianization of the Iberian Peninsula. In the early 5th century, Paulus Orosius (a friend of Augustine of Hippo) wrote several theological works that expounded the Christian faith. While thanks to the work of Saint Martin of Braga the Suebi in Iberia renounced the Arian and Priscillianist heresies during two synods held here in the 6th century.[5] It is also worth noting that Rechiar, the suebi king, was also the first Germanic king in Europe to convert to Chalcedonian Christianism, predating Clovis of the Franks.[8] At the time, Martin also founded an important monastery in Dumio (Dume), and it was in Braga that the Archbishopric of Braga held their councils. There were also some attempts at further elevating the religious status of the city, such as Paulus Orosius and Avitus of Braga's attempt at bringing relics of Saint Stephen, from the Holy Land to Braga. Originally, Avitus entrusted the delivery of the relics to Paulus Orosius, however, after arriving at Majorca, the theologian heard news of the invasion of the peninsula by the Vandals and halted his pilgrimage to return to North Africa. The relics never reached their destination and their fates are unknown.[9]

As a consequence, the Archbishops of Braga later claimed the title of Primatus Totus Hispania, claiming supremacy over the entire Hispanic church. Yet, their authority was never accepted throughout Hispania, and today they only retain the title of Primate of Portugal. The bishop Balconius, who was later elevated to become the first Archbishop of Braga, and according to later sources, was also the first to be given said title.[10][11]

The transition from Visigothic reigns to the Muslim conquest of Iberia was very obscure, representing a period of decline for the city. The Moors briefly captured Braga in 714-716, but were repelled by Christian forces under Alfonso I of Asturias in 741,[12] (alongside Chaves, Porto and Lamego), with intermittent attacks until 868 when they were definitively ousted by Alfonso III of Asturias. The bishopric was restored in 1070 and elevated to new heights. The first new Archbishop, Peter of Braga (?-1096), immediately started rebuilding the Cathedral (which was modified many times during the following centuries). According to historical records and oral tradition, the Archbishop Diego Gelmírez of Santiago de Compostela, fearing the rise of the Cathedral of Braga, stole the relics of Braga's saints in an attempt to diminish the religious importance of the city.[11] The relics only returned to Braga in the 1990s.

When, after his death, Alfonso III the Great of the Kingdom of Asturias divided his kingdom among his sons in 908, he assigned the Kingdom of Galicia to Ordoño of Galicia, who established his capital in Braga.[13] Between 1093 and 1147, Braga became the residential seat of the Portuguese court. In the early 12th century, Count Henry of Portugal and bishop Geraldo de Moissac reclaimed the archbishopric seat for Braga, with power over a large area in Iberia. The medieval city developed around the cathedral, with the maximum authority in the city retained by the archbishop.

Braga in the Kingdom of Portugal

Braga as the main center of Christianity in Iberia, during the Reconquista (until the emergence of Santiago de Compostela and, later, the conquest of Toledo from the Muslims, in 1085), held a prominent stage in medieval politics, being a major contributor to the Independence of Portugal with the intervention of the Archbishop D. Paio Mendes in the Vatican, with Pope Alexander III, which lead to the promulgation of the Bula Manifestis Probatum, in 1179, recognizing Portugal as an independent Kingdom under D. Afonso I Henriques. It is traditionally told that the future king was baptized by Saint Gerald of Braga, although the exact location is still being debated.[14] Because of this support for D. Afonso Henriques, the new king gave large privileges to the city of Braga handing it over to direct control of the Church, basically making it a personal fiefdom of the Archbishop. This legal particularism continued all throughout history until the instauration of the Republic giving the city and its surrounding area the nickname of "Paiz Bracarense" (roughly translated as "Country of Braga").[15]

In the 16th century, due to its distance from the coast and provincial status, Braga did not profit from the adventures associated with the Age of Portuguese Discoveries (which favoured cities like Lisbon, Évora and Coimbra, new seats for the Portuguese court). Yet, Archbishop Diogo de Sousa, who sponsored several urban improvements in the city, including the enlargement of streets, the creation of public squares and the foundation of hospitals and new churches, managed to modernize the community. He expanded and remodelled the cathedral by adding a new chapel in the Manueline style, and generally turning the mediaeval town into a Renaissance city.

A similar period of rejuvenation occurred during the 18th century, when the archbishops of the House of Braganza contracted architects like André Soares and Carlos Amarante, to modernize and rejuvenate the city; they began a series of architectural transformations to churches and civic institutions in the Baroque style, including the municipal hall, public library, the Sanctuary of Bom Jesus do Monte and many urban palaces. D. Luís de Sousa was another main archbishop who, with other merits, ordered the Church of the Parish of Saint Victor to be rebuilt, ordered the Campo de S. Ana to be enlarged, to rebuild the Church of S. Vicente, to requalify the Chapel of S. Sebastian and the construction of the Igreja dos Congregados which would later be monumentalized into the current version of the Basilica of the Congregados. Likewise, under the auspices of this diplomatic archbishop, the canon of the Braga Chapter, João Meira Carrilho, ordered the construction of the Chapel of the Congregation of the Oratory that existed within the Campo de S. Ana (modern day Avenida Central).[16] The old fortress built on top of the Roman amphitheatre still stood in the 18th century (a description of it was made during the reign of Queen D. Maria I), in the southern part of Maximinos,[5] but in search of the Roman foundations it was eventually torn down and it is now an archaeological site.

In 1758, Braga, like many other places, was included in the census requested by the monarchy, under the 1st Marquis of Pombal. These records are known as the Parochial Memories (Memórias Paroquiais) which can be consulted through various sources.[17]

In March 1809 it was the scene of the Battle of Braga, when French troops under Marshal Soult took the town from its Portuguese garrison. With the invasion of French troops, during the Peninsular Wars the city was relegated, once again, to a provincial status. But, by the second half of that century, with influence from Portuguese immigrants living in Brazil, new money and tastes resulted in improvements to architecture and infrastructures.

Braga in the Republic

The Castle of Braga, previously located in the city center, was destroyed in 1905 (to great popular fanfair), despite attempts to save it by several people such as archaeologist Albano Belino, who tried to change the location of his municipal museum to the building in an attempt to protect it. Belino, disgusted, suffered from a stroke, passing away the following year and ending up donating his estate to the Archaeological Museum of the Martins Sarmento de Guimarães Society. Albano Belino's dream of creating a museum in Braga was only realized in 1918, with the founding of a museum directly precursor to the Dom Diogo de Sousa Regional Museum of Archaeology.

On May 28, 1926, General Gomes da Costa began his march to Lisbon starting the Revolution of May 28, where he abolished the First Republic and implementing the dictatorial government of the Estado Novo. In the tenth year anniversary of the Revolution, dictator António de Oliveira Salazar, visited the city prompting a large fair, a parade and a speech, which he gave on the balcony of the Town Hall. Afterwards, the dictator would return several times to the city in its anniversary, such as the 40º anniversary.[18]

In the 20th century Braga faced similar periods of growth and decline; demographic and urban pressures, from urban-to-rural migration meant that the city's infrastructures had to be improved in order to satisfy greater demands.

Geography

Physical geography

.jpg.webp)

Situated in the heart of Minho, Braga is located in a transitional region between the east and west: between mountains, forests, grand valleys, plains and fields, constructing natural spaces, moulded by human intervention. Geographically, with an area of 184 square kilometres (71 sq mi) it is bordered in the north by the municipalities of Vila Verde and Amares, northeast and east by Póvoa de Lanhoso, south and southeast with Guimarães and Vila Nova de Famalicão and west by the municipality of Barcelos.[19]

The topography in the municipality is characterized by irregular valleys, interspersed by mountainous spaces, fed by rivers running in parallel with the principal rivers. In the north it is limited by the Cávado River, in the south by terrain of the Serra dos Picos to a height of 566 metres (1,857 ft) and towards the east by the Serra dos Carvalhos to a height of 479 metres (1,572 ft), opening to the municipalities of Vila Nova de Famalicão and Barcelos. The territory extends from the northeast to southwest, accompanying the valleys of the two rivers, fed by many of its tributaries, forming small platforms between 20 metres (66 ft) and 570 metres (1,870 ft).

The municipality lies between 20 metres (66 ft) and 572 metres (1,877 ft), with the urbanized centre located at approximately 215 metres (705 ft). In the north, where the municipality is marked by the Cavado, the terrain is semi-planar, the east is mountainous owing to the Serra do Carvalho 479 metres (1,572 ft), Serra dos Picos 566 metres (1,857 ft), Monte do Sameiro 572 metres (1,877 ft) and Monte de Santa Marta 562 metres (1,844 ft). Between the Serra do Carvalho and Serra dos Picos is the River Este, forming the valley of Vale d’Este. Similarly, between the Serra dos Picos and Monte do Sameiro exists the plateau of Sobreposta-Pedralva. To the south and west, the terrain is a mix of mountains, plateaus and medium-size valleys, permitting the passage of the River Este, and giving birth to other confluences including the River Veiga, River Labriosca and various ravines.

Climate

Braga has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate similar to other cities in the northwest Iberian Peninsula except for having significantly hotter summer temperatures due to being some distance from the ocean: the absolute maximum is as much as 5 °C (9 °F) higher than neighbouring A Coruña or Santiago de Compostela. The highest and lowest recorded temperatures are 42.2 °C (108.0 °F) and −6.3 °C (20.7 °F) respectively. The climate is affected by the Atlantic Ocean which influences westerly winds that are channeled through the region's valleys, transporting large humid air masses. Consequently, the climate tends to be pleasant with clearly defined seasons. The air masses have the effect of maintaining morning relative humidity around 80%: annual mean temperatures hover between 12.5 °C (54.5 °F) and 17.5 °C (63.5 °F). Owing to nocturnal cooling, frost usually forms frequently between three and four months of the year (about 30 days of frost annually), and annually the region receives 1,449 millimetres (57.0 in) of precipitation, with the major intensity occurring between fall/winter and spring.

| Climate data for Braga, 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1941–2006, altitude: 190 m (620 ft) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.0 (75.2) |

23.5 (74.3) |

29.5 (85.1) |

31.0 (87.8) |

35.5 (95.9) |

38.5 (101.3) |

38.5 (101.3) |

42.2 (108.0) |

38.5 (101.3) |

33.3 (91.9) |

28.5 (83.3) |

24.1 (75.4) |

42.2 (108.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.7 (56.7) |

14.8 (58.6) |

17.6 (63.7) |

18.3 (64.9) |

21.1 (70.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

27.8 (82.0) |

28.0 (82.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

20.9 (69.6) |

16.8 (62.2) |

14.4 (57.9) |

20.3 (68.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 9.0 (48.2) |

9.9 (49.8) |

12.3 (54.1) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

19.5 (67.1) |

21.4 (70.5) |

21.4 (70.5) |

19.4 (66.9) |

15.9 (60.6) |

12.3 (54.1) |

10.2 (50.4) |

15.0 (59.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.3 (39.7) |

4.9 (40.8) |

7.0 (44.6) |

7.9 (46.2) |

10.4 (50.7) |

13.5 (56.3) |

14.9 (58.8) |

14.7 (58.5) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

7.7 (45.9) |

6.0 (42.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −6.3 (20.7) |

−4.5 (23.9) |

−5.0 (23.0) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

−0.5 (31.1) |

3.3 (37.9) |

7.5 (45.5) |

6.7 (44.1) |

3.8 (38.8) |

2.5 (36.5) |

−1.7 (28.9) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 176.4 (6.94) |

114.8 (4.52) |

121.6 (4.79) |

130.8 (5.15) |

112.9 (4.44) |

48.6 (1.91) |

22.0 (0.87) |

34.0 (1.34) |

81.7 (3.22) |

191.7 (7.55) |

193.9 (7.63) |

220.2 (8.67) |

1,448.6 (57.03) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 14.8 | 13.5 | 12.2 | 13.5 | 13.4 | 8.2 | 5.4 | 4.7 | 7.4 | 12.7 | 13.1 | 15.5 | 134.4 |

| Source: Instituto de Meteorologia[20] | |||||||||||||

Human geography

|

The municipality is densely populated, with approximately 962 inhabitants per square kilometre, equivalent to 181,474 residents (2011); it is one of the more populous territories in Portugal, as well as one of the "younger" markets.[21] The majority of the population concentrates in the urban area of Braga, itself, where densities are more than 10000 per square kilometre.

The Bracarense population consists of approximately 78954 male and 85238 female individuals, with 35% of the population less than 25 years of age, while seniors conform to 11% of the population; the working population of the municipality occupies 54% of this structure.[21] Although largely native Portuguese, other segments of the population include Brazilians, Africans (principally from the former Portuguese colonies), Chinese and eastern European peoples, namely Ukrainians.[21]

.JPG.webp)

The urban structure includes approximately 70,268 residences (2001), even as the typical classic representation of family only includes 51,173 members in the municipality.[21] The "extra" homes are primarily temporary residences, normally for students, migrant workers and professionals working in the city. There is, also, a great number of homes owned by Portuguese residents living overseas (who use the homes periodically while in Portugal) even as constant and development has attracted new growth in the population.[21] Further, the difference in resident to transitory population means that, on average, the population of Braga hovers between 174,000 and 230,000 individuals annually.[21]

Growth in the population, roughly 16.2% between 1991 and 2001, occurred mainly in the older suburban civil parishes, such as Nogueira (now abolished) (124.6%), Frossos (now abolished) (68.4%), Real (now abolished) (59.8%) and Lamaçães (now abolished) (50.9%).[21][22]

Civil parishes

Administratively, the municipality is divided into 37 civil parishes (freguesias):[23]

- Adaúfe

- Arentim e Cunha

- Braga (Maximinos, Sé e Cividade)

- Braga (São José de São Lázaro e São João do Souto)

- Cabreiros e Passos (São Julião)

- Celeirós, Aveleda e Vimieiro

- Crespos e Pousada

- Escudeiros e Penso (Santo Estêvão e São Vicente)

- Espinho

- Esporões

- Este (São Pedro e São Mamede)

- Ferreiros e Gondizalves

- Figueiredo

- Gualtar

- Guisande e Oliveira (São Pedro)

- Lamas

- Lomar e Arcos

- Merelim (São Paio), Panoias e Parada de Tibães

- Merelim (São Pedro) e Frossos

- Mire de Tibães

- Morreira e Trandeiras

- Nogueira, Fraião e Lamaçães

- Nogueiró e Tenões

- Padim da Graça

- Palmeira

- Pedralva

- Priscos

- Real, Dume e Semelhe

- Ruilhe

- Santa Lucrécia de Algeriz e Navarra

- São Vicente

- São Victor

- Sequeira

- Sobreposta

- Tadim

- Tebosa

- Vilaça e Fradelos

There is no formal city government, only municipal government authority, with local administration handled by the individual juntas de freguesia or civil parish councils.

Economy

The major industries in the municipality are construction, metallurgy and mechanics, electrical and electronic equipment, software development and web design. The computer industry is significant. Braga hosts PRIMAVERA – Business Software Solutions SA (PRIMAVERA BSS) company headquarters,[24][25] a Portuguese multinational software company best known for its leading enterprise project management software. The INL - International Iberian Nanotechnology Laboratory, a joint research center in nanotechnology established and funded by both the Portuguese and the Spanish governments, is also headquartered in Braga. The automotive industry has a long history in Braga. Aptiv operates a technical center for the development and production of automotive infotainment systems.[26] This plant was previously owned by Grundig. Next to Aptiv, Robert Bosch GmbH operates a similar technical center, mainly for branches of infotainment and sensors. This plant was previously founded by Blaupunkt. Bosch has been working closely with the University of Minho in Portugal since 2012, producing one of the country's largest university-corporate partnerships. In the process, many projects for the mobility of the future are being tackled. In 2018, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Portuguese Prime Minister António Costa were on site for the launch of a new technology campus.[27] The university, headquartered in Braga, is also by itself a major driving force of the city's economy.

Transport

The municipality has a small-sized airfield (Aerodromo de Braga) in Palmeira. The major international airport used by the people of Braga is the Sá Carneiro International Airport (also known as Porto Airport) located 50 kilometres (31 mi) away, in Porto Metropolitan Area. Access to the international airport located near Porto is made by public transit fom Braga city centre (roughly 40 minutes) or aerobus (50 minutes).

Braga is serviced by both regional and high-speed rail connection to major urban centres in the country and abroad.

It has an efficient bus network (TUB - Transportes Urbanos de Braga) with 76 lines in the urban area and over a 300 km network.

Architecture

Central Avenue in Braga

Central Avenue in Braga.jpg.webp) Campo das Hortas, Braga

Campo das Hortas, Braga

.JPG.webp)

The region of Braga is scattered with Neolithic, Roman, Medieval and Modernist monuments, buildings and structures attracting tourists. Although there are many examples of these structures, only the following have been classified by the Instituto de Gestão do Património Arquitectónico e Arqueológico as National Monuments:

Archaeological

- Castro of São Mamede (Castro de Monte Redondo/Castro Monte Cossourado/Castro de São Mamede)

- Roman milestones, several Roman-era granite markers currently on display at the Museum D. Diogo de Sousa, dating from AD 41 to 238, that is, the reigns of Emperor Claudius to Maximinus II.[28]

- Roman Thermae of Maximinus (Portuguese: Termas romanas de Maximinos/Alto da Cividade/Colina dos Maximinos), discovered in the 20th century, the thermae occupy 800 square metres (8,600 sq ft), in the civil parish of Braga (Maximinos, Sé e Cividade), and were constructed in the 1st to late 3rd century;[29]

Civic

- Arch of Porta Nova/Rua de Souto (Arco da Porta Nova/Arco da Rua do Souto), a Baroque and Neoclassical arch, designed by André Soares in the late 18th century, and decorates the western gate of a medieval wall. It was opened in 1512 and since has been traditionally used to present to promote to visiting dignitaries and celebrities.[30]

- Palace of the Falcões (Portuguese: Palácio dos Falcões/Governo Civil de Braga), a Baroque-era palace originally commissioned by Francisco de Meira Carrilho on 23 July 1703, and later, upon successive renovations, used by the Civil Governor's residence;

- Fountain of the Idol (Portuguese: Fonte do Ídolo), the 1st century Roman fountain dedicated to an indigenous god, located in the central civil parish of Braga (São José de São Lázaro e São João do Souto);

- Fountain of the Iron Waters (Portuguese: Fonte das Águas Férreas), following the discovery in July 1173 of iron-rich springs in the parish of Fraião, Archbishop Gaspar de Bragança ordered the municipal council to begin the canalization of these waters for public use, giving rise to a series of fountains, such as the Baroque decorated main fountain;

- Hospital of São Marcos (Portuguese: Hospital de São Marcos), with a façade comparable to any religious monument in the city, the Hospital of São Marcos, is an example of the complex Baroque style of Carlos Amarante, featuring ornate double belfry and accents;

- Pillory of Braga (Portuguese: Pelourinho de Braga), the 15th century pillory, that marks municipal authority for the town, was constructed, demolished and moved various times, before being relocated on the grounds of the Sé Cathedral;[31]

- Palace of Raio (Portuguese: Palácio de Raio), an 18th-century Baroque-Rococo urban residence, with richly decorated blue azulejo façade of Andre Soares;

- Residence of the Crivos (Portuguese: Casas das Gelosias/Casa dos Crivos), a Renaissance-era shop-residence constructed outside the old walls characteristic of late Renaissance architecture and one of the few examples of a building covered in wood-lattice façade from this period.

- Seven Sources Aqueduct (Portuguese: Sete Fontes), a complex network of aqueducts that provided potable water to citizenry of Braga;

- Theatro Circo (Portuguese: Teatro Circo de Braga), 20th century revivalist theatre, known for its architecture, as much for the films, theatre plays and performances;

- Bridge of Prado (Ponte do Prado)

- Bridge of Prozelo (Ponte de Prozelo/Ponte do Porto)

Military

- Tower of Santiago (Portuguese: Torre de Santiago e troço das antigas muralhas de Braga), part of the ancient walls of Braga, the Tower of Santiago was designed by Portuguese Baroque master André Soares, based on a mixture of Gothic, Baroque and Rococo elements;

- Tower of Castle of Braga (Castelo de Braga), actually the remnants of the castle's keep, constructed during the reign of King Denis of Portugal, which was part of the defensive system of the city of Braga, and included a semi-circular walled enclosure centred on the Sé Cathedral.[32]

Religious

- Archiepiscopal Palace of Braga (Portuguese: Antigo Paço Arquiepiscopal de Braga), between the 14th–18th centuries, a religious residence, but after the 20th century, the home of the municipal offices, public library and archive;

- Chapel of the Espírito Santo (Portuguese: Capela do Espírito Santo), an example of mixed styles, the chapel includes elements of Baroque, Neoclassical and Manerist eras;

- Chapel of Nossa Senhora da Consolaçã (Portuguese: Capela de Nossa Senhora da Consolação), a simple single-nave chapel constructed in the Baroque-style

- Chapel of São Bento (Portuguese: Capela de São Bento), constructed in the middle of the 18th century, the chapel was blessed by Archbishop José of Bragança in 1755;

- Chapel of Senhor do Bom Sucesso (Portuguese: Capela do Senhor do Bom Sucesso), a Baroque and Neoclassical chapel, is highlighted by a main façade, typical of André Soares, but constructed by Carlos Amarante, at the beginning of his career, who timidly applied Neoclassical decorative elements;

- Chapel of the Coimbras (Capela de Nossa Senhora da Conceição/Capela dos Coimbras/Capela do Senhor Morto), a Manueline chapel, probably designed by Castillian architect Filipe Odarte, with sculptures attributed to Hodart, an altar by João de Ruão and posterior tomb sculptures by the same artist.[33]

- Church of Santa Cruz (Portuguese: Igreja de Santa Cruz), and the Hospital of the Brotherhood of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem (Portuguese: Irmandade de Santa Cruz de Jerusalem), constructed in 1581, and later supported by the nuns of the Order Hospitaler;

- Church of Santa Eulália (Portuguese: Igreja de Santa Eulália), is a 13th–14th century Romanesque church, located near Bom Jesus do Monte;

- Church of Santa Maria (Portuguese: Igreja Paroquial de Ferreiros/Igreja de Santa Maria), constructed in 1560, under the orders of Archbishop Bartolomeu dos Mártires, as a church of the Society of Jesus;

- Church of Santo André (Portuguese: Igreja Paroquial de Gondizalves/Igreja de Santo André), an example of the reformulations of the Modernist aesthetic of the mid-20th century: the 18th-century church was adapted and expanded after the parish's de-annexation in 1975;

- Chapel of São Frutuoso, also known as the Chapel of São Frutuoso of Montélios or the Chapel of São Salvador of Montélios, is a pre-Romanesque chapel, forming part of group of religious buildings that include the Royal Church originally built by the Visigoths in the 7th century, in the form of a Greek cross.[34]

- Chapel of São Sebastião das Caravelheiras (Portuguese: Capela de São Sebastião das Caravelheiras)

- Church of São Martinho (Portuguese: Igreja Matriz de Espinho/Igreja de São Martinho), the Baroque and Classical parochial church of Espinho, known for its ornate façade and belfrey, as well as its Rococo interior;

- Church of São Miguel de Frossos (Portuguese: Igreja Paroquial de Frossos/Igreja de São Miguel), a 16th-century parochial church in the civil parish of Frossos;

- Church of São Miguel de Gualtar (Portuguese: Igreja Paroquial de Gualtar/Igreja de São Miguel), part of the intense building period of the 16th–17th century, the parochial church of Gultar was constructed in the 17th century, but later remodelled during the 18th century;

- Church of São Paio (Portuguese: Igreja Paroquial de Arcos/Igreja de São Paio), located in Arcos, the church is an early 18th-century church (built in 1706);

- Church of São Paulo (Portuguese: Igreja de São Paulo e Seminário de Santiago), the historical seminary and church of Saint Paul with its contrast between stoic façade and decorated Baroque interior, built in the era of archbishop Bartholomew;

- Church of São Pedro de Lomar (Portuguese: Igreja de São Pedro de Lomar), remnant of ancient Benedictine monastery of São Pedro in Lomar, the Church of Saint Peter exemplifies a mix of Baroque, Mannerist and Neoclassical architecture;

- Church of São Pedro de Maximinos (Portuguese: Igreja de São Pedro de Maximinos), known for the missing organ of organist Manuel de Sá Couto;

- Church of São Tiago (Portuguese: Igreja Paroquial da Cividade/Igreja de São Tiago)

- Church of São Vicente (Portuguese: Igreja de São Vicente)

- Convent of Nossa Senhora do Carmo (Portuguese: Convento de Nossa Senhora do Carmo), principally recognizable for its central spire/belfrey, which was designed by João de Moura Coutinho de Almeida e Eça, and constructed in the 17th–18th century;

- Church of the Misericórdia (Portuguese: Igreja da Misericórdia)

- Church of the Third Order of St. Francis (Portuguese: Igreja dos Terceiros), the Terceiros began the process of constructing their church in 1685, which they dedicated to Our Lady of Conception (Portuguese: Nossa Senhora da Conceição);

- Church, Convent and College of the Congregation of São Filipe de Néri (Portuguese: Igreja dos Congregados), attributed to the architect André Soares, for the complex/risky façade of the church and corner convent windows, Monk's chapel (or Chapel of Our Lady of the Appearance), and retable of Our Lady of Pain (Portuguese: Nossa Senhora das Dores)

- Convent of Nossa Senhora da Conceição (Portuguese: Convento da Nossa Senhora da Conceição), which includes the Chapel of São Domingos, an 18th-century convent, home to the Instituto Monsenhor Ariosa;

- Convent of Pópulo (Portuguese: Convento do Pópulo), the Mannerist, Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical austere elements of the convent belying the extravagant interior, that was originally the home to Augustine monks, highlighted by the Baroque façade of the Church of Pópulo (Portuguese: Igreja de Pópulo);

- Convent of Salvador (Portuguese: Convento do Salvador/Lar Conde de Agrolongo), began with the need to transfer the nuns from the Monastery of Vitorino das Donas in 1528

- Convent of São Francisco de Montélios (Portuguese: Convento de São Francisco/Igreja de São Jerónimo de Real), the Baroque, Rococo and Neoclassical convent, highlighted by the imposing three-storey façade of the Church of São Jerónimo;

- Cross of Nossa Senhora dos Aflitos (Portuguese: Cruzeiro da Nossa Senhora dos Aflitos), a Baroque cross on an ionic column, with an image of Christ in wood, surmounted by a rectangular Tuscan colonnade and roof;

- Cross of the Espírito Santo (Portuguese: Cruzeiro do Espírito Santo)

- Monastery of Dumio (Portuguese: Ruínas Arqueológicas de São Martinho de Dume), the ancient religious seat founded by Martin of Braga in the provincial centre of Dume;

- Monastery of Tibães (Portuguese: Mosteiro de Tibães), the 17th–18th century Benedictine monastery renowned for the ornate/artistic gilt work in its chancel and altars;

- Sanctuary of Bom Jesus do Monte (inscribed on the World Heritage List in July, 2019[35]), constructed on Monte Santo, overlooking the urban sprawl of Braga, the 18th to early-19th century, Neoclassic sanctuary and church (itself preceded by Baroque stairway), is reachable by trail or Bom Jesus funicular (one of the oldest in Iberian Peninsula);

- Sanctuary of Nossa Senhora do Sameiro (Portuguese: Santuário de Nossa Senhora do Sameiro), isolated on the hilltop of Monte do Sameiro, the church and retreat began in 1861, from the mind of Father Martinho António Pereira da Silva, who wished to construct a monument dedicated to Our Lady of the Conception;

- Sanctuary of Santa Maria Madalena (Portuguese: Santuário de Santa Maria Madalena/Santuário da Falperra), located on Monte Falperra, the Baroque-era sanctuary church, was designed by local architect André Soares, incorporating decorative elements into a two-bell tower homage to the Mary Magdalene;

- Sé Cathedral of Braga (Portuguese: Sé Catedral de Braga)

- Wayside shrine of São Brás (Portuguese: Alminhas de São Brás), although conjecturally a contemporary monument, the wayside shrine in Ferreiros has the characteristics of many Baroque monuments in Braga;

- Cross of Campo das Hortas (Cruzeiro do Campo das Hortas)

- Cross of Santana (Cruzeiro de Santa Ana/Cruzeiro de Santana)

- Cross of Tibães (Cruzeiro de Tibães)

Museums

.jpg.webp)

In addition, many of the district's treasures and historical artifacts are housed in several museums that are scattered throughout the city, such as:

- Museum of the Biscainhos (Portuguese: Museu dos Biscainhos), housed in the historical Palace of the Biscainhos, the museum exhibits a permanent collection of decorative art, that includes furniture, ceramics, European and Oriental porcelain, European Glass, European and Portuguese watches and clocks;

- Treasure Museum of the Sé Cathedral (Portuguese: Tesouro Museu da Sé Catedral), the collection varies, but collects together artefacts from the 16th to 18th century during the period of religious/cultural exploration, associated with the cathedral, including images and azulejo tiles;

- Museum of Image (Portuguese: Museu da Imagem), dedicated to photography, located near the Arco da Porta Nova and Braga Castle;

- Museum Medina (Portuguese: Museu Medina), located in the same building as the Museum of Pius XII, the collection is the home to the 83 oil paintings and 21 drawings of the painter Henrique Medina;

- Museum of Nogueira da Silva (Portuguese: Museu Nogeuira da Silva), bequeathed to the University of Minho, the collection includes artefacts, paintings, furniture and sculptures collected over a lifetime, such as Renaissance artwork, 17th furniture, ceramics and objects in ivory, silver and religious art;

- Museum of Pius XII (Portuguese: Museu Pio XII), housing a collection of Palaeolithic, Neolithic and Bronze Age implements, Pre-historic and Luso-Roman pottery;

- Dom Diogo de Sousa Museum (Portuguese: Museu D. Diogo de Sousa), its collection includes many items discovered during archaeological excavations within the municipality, extending as far back as the Palaeolithic to the Middle Ages.

- Museum of String Instruments (Portuguese: Museu dos Cordofones), the collection features Portuguese instruments as far back as the Middle Ages including Cavaquinhos, Portuguese guitars, Mandolins and banjos among others.

Education

%252C_Braga.jpg.webp)

The city is the headquarters and main campus for the Universidade do Minho (Minho University), a public university founded in 1973. A campus of Portugal's oldest private university of Portugal, the Universidade Católica Portuguesa, was also established in 1967, as well as the Escola Secundária Sá de Miranda (the oldest Secondary school in Braga).

In the late 2000s, the International Iberian Nanotechnology Laboratory also opened their international research centre in the city.

The Braga Pedagogical Farm is a farm dealing with animals and agriculture, welcoming extra-curricular activities from schools and visitors.

Sports

Braga's football team, Sporting Clube de Braga, was founded in 1921 and play in the top division of Portuguese football, the Liga Portugal bwin, from Braga Municipal Stadium, carved out of the Monte Castro hill that overlooks the city. Braga has had considerable success in recent years, winning the Taça de Portugal (Portuguese Cup) for the second time in 2016 and the third in 2021 and reaching the Europa League final in 2011, which they lost to fellow Portuguese side FC Porto.

The Rampa da Falperra, a round of the European Hillclimb Championship, is held every year in the outskirts of the city.

The Circuito Vasco Sameiro and adjacent the Kartódromo Internacional de Braga are located around the local airfield. The racing track held European Touring Car Cup events in 2009 and 2010, and the KIB has held rounds of the Karting World Championship.

Notable citizens

Public service

- Avitus of Braga (?- ca. 440 AD), produced a first person account of the miraculous finding of St. Stephen's tomb.

- Saint Ovidius (martyred 135 AD) third Bishop of Braga, buried in the cathedral.

- Saint Engratia venerated as a virgin martyr and saint, tradition is that she was martyred with 18 companions in 303AD

- Paulus Orosius (ca.383 – ca.420), historian and theologue from the Braga diocese

- Hermeric (died 441), landlord and then king of the Suebi with capital in Braga, from at least 419 and possibly as early as 406 until his abdication in 438.

- Martin of Braga (c. 520–580), Bishop of Braga in 562–579, converted the Suebi to Catholicism.

- Henry, Count of Portugal (1066–1112) Count of Portugal 1093–1112, turned Braga into his capital

- Teresa of León, Countess of Portugal (1080–1130) was married to Count Henry in 1094

- Antipope Gregory VIII (died 1137) born Mauritius Burdinus, the second Archbishop of Braga

- D. Paio Mendes (died 1137): he was the Archbishop of Braga from 1118 to 1137

- Pope John XXI (ca.1215–1277) born Pedro Julião, Archbishop of Braga 1272–1275, elected Pope in 1276.

- Francisco Sanches (ca.1550 – ca.1623) a skeptic, philosopher and physician of Sephardi Jewish origin

- Miguel de Carvalho (1579–1624), a Roman Catholic missionary, was burned at the stake in Japan, beatified in 1867.

- Manuel António Martins (1772–1845) governor of Cape Verde and Portuguese Guinea, 1833 to 1835

- João Crisóstomo de Amorim Pessoa (1810–1888) Bishop of Santiago de Cabo Verde and archbishop of Goa and Braga

- Manuel Gomes da Costa (1863–1929) an army officer and politician, the tenth President of the Portuguese Republic and led the famous 28 May 1926 coup d'état in Braga

- Domingos Leite Pereira (1882–1956), Portuguese politician of the Portuguese First Republic

- Salgado Zenha (1923–1993), a Portuguese left-wing politician and lawyer.

- Ricardo Rio (born 1972) an economist, politician and current Mayor of Braga.

Arts & Science

- Gabriel Pereira de Castro (1571-1632) a priest, lawyer and poet.

- João Antunes (1642–1712), an important architect credited for introducing baroque architecture

- André Soares (1720–1769) architect of several important Rococo buildings in Braga area.

- Carlos Amarante (1748–1815) an architect who favoured neoclassical architecture

- Adriano de Paiva (1847–1907) a scientist and pioneer of the telectroscope.

- Albano Ribeiro Belino (1863-1906) a journalist and archaeologist who studied the roman and pre-historic ruins in Braga.

- Elísio de Moura (1877–1977) a physician, professor and leading psychiatrist

- Lúcio Alberto Pinheiro dos Santos (1889-1950) philosopher, coined the term rhythmanalysis

- Luís de Almeida Braga (1890–1970) a Portuguese writer and politician, in the Integralismo Lusitano movement.

- António Variações (1944–1984), innovative pop composer and singer

- Torcato Sepulveda (1951–2008), an influential Portuguese newspaper journalist.

- Sara Braga Simões (born 1975) an operatic soprano

Sport

- Carlos Carvalhal (1965) a former footballer with 259 club caps and manager of S.C. Braga.

- Litos (born 1974) a former footballer with 433 club caps

- Henrique (born 1980) a former footballer with 451 club caps

- Pedro Pereira (born 1984) a former footballer with over 460 club caps

- Emanuel Silva (born 1985) a sprint canoeist and silver medallist at the 2012 Summer Olympics

- Carole Costa (born 1990) a footballer with 133 caps for the Portuguese female national football team

- Júlio Ferreira (born 1994) a taekwondo practitioner

- Diogo Dalot (born 1999) a footballer with Manchester United F.C. and 6 caps for Portugal

International relations

Bissorã, Guinea Bissau

Bissorã, Guinea Bissau Clermont-Ferrand, France

Clermont-Ferrand, France Cluj-Napoca, Romania

Cluj-Napoca, Romania Cuenca, Ecuador

Cuenca, Ecuador Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine

Ivano-Frankivsk, Ukraine Poggibonsi, Italy

Poggibonsi, Italy Puteaux, France

Puteaux, France Ribeira Brava, Cape Verde

Ribeira Brava, Cape Verde Santa Fe, Argentina

Santa Fe, Argentina Tarrafal de São Nicolau, Cape Verde

Tarrafal de São Nicolau, Cape Verde

See also

References

- "Statistics Portugal". www.ine.pt. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- Eurostat Archived 7 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Braga 2012 Capital Europeia da Juventude (in Portuguese), Braga, Portugal, 2012, archived from the original on 4 May 2012, retrieved 19 April 2012

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Machado, José Barbosa (1 January 2014). Introdução à História da Língua e Cultura Portuguesas. Edições Vercial. ISBN 9789897001857. Retrieved 27 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- Marques, António Henrique R. de Oliveira (1997). História de Portugal : manual para uso de estudantes e outros curiosos de assuntos do passado pátrio (13th ed.). Lisboa: Presença. pp. 43–44. ISBN 972-23-2189-7. OCLC 476465662.

- Thompson, E. A. Romans and Barbarians: The Decline of the Western Empire. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982. ISBN 0-299-08700-X pp. 153–154.

- Díaz Martínez, Pablo de la Cruz (2011). El reino suevo (411-585). Tres Cantos, Madrid, España. ISBN 978-84-460-3648-7. OCLC 958059531.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Visigothic Spain : new approaches. Edward James. Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1980. ISBN 0-19-822543-1. OCLC 5100979.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Wace, Henry; Piercy, William Coleman, eds. (2014). A dictionary of early Christian biography: and literature to the end of the sixth century A.D. ; with an account of the principal sects and heresies. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publ. pp. 1263–1264. ISBN 978-1-61970-269-1.

- Aranha, Boaventura Maciel (1761). Cuidados da morte e descuidos da vida... Com a addicao das prodigios as vidas dos dous mayores santos... na officina de Francisco Borges de Sousa. p. 276.

- Cunha, D. Rodrigo da (1634). Primeira [-segunda] parte, da historia ecclesiastica dos arcebispos de Braga, e dos Santos, e Varoes illustres, que florecerão neste arcebispado. Por dom Rodrigo da Cunha arcebispo, & senhor de Braga, primàz das Hespanhas (in Portuguese). Vol. II. pp. 18–22.

- Menéndez Pidal, Ramón (1906). PRIMERA CRÓNICA GENERAL. ESTORIA DE ESPAÑA DE ALFONSO X (2022 ed.). Biblioteca Digital de Castilla y León. p. 357. Retrieved 10 June 2023.

- de Braga, Bernardo (1843). da Silveira Pinto Albano, Antero (ed.). Tratado sobre a precedencia do Reino de Portugal ao Reino de Napoles. Typogr. da revista. p. 25.

- Cunha, D. Rodrigo da (1634). Primeira [-segunda] parte, da historia ecclesiastica dos arcebispos de Braga, e dos Santos, e Varoes illustres, que florecerão neste arcebispado. Por dom Rodrigo da Cunha arcebispo, & senhor de Braga, primàz das Hespanhas (in Portuguese). Vol. II. pp. 2–29.

- Bandeira, Miguel (1993). "O espaço urbano de Braga em meados do séc. XVIII". Revista da Faculdade de Letras - Geografia. IX: 171–173.

- Portocarrero, Gustavo (2010). Braga na Idade Moderna : paisagem e identidade. Tomar: CEIPHAR. pp. 81–100. ISBN 978-972-95143-2-6. OCLC 733958410.

- Capela, José Viriato (2003). As freguesias do distrito de Braga nas Memórias Paroquiais de 1758: a construção do imaginário minhoto setecentista.

- "Salazar no 40.º Aniversário do 28 de Maio de 1926". RTP.

- Pereira, P. Gomes (2009), "Caracterização do Concelho de Braga", Diagnóstico do Concelho de Braga (PDF) (in Portuguese), Braga, Portugal: Unidade de Saúde Pública de Braga, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015, retrieved 21 March 2012

- "Normals Climatológicas". Instituto de Meteorologia, IPMA. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Census de 1991, 2001 e Território em números de 2004 (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: INE – Instituto Nacional de Estatistica, 2004, retrieved 24 March 2012

- "0000200147" (PDF). DRE (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 29 December 2022.

- Diário da República. "Law nr. 11-A/2013, pages 552 26–28" (PDF) (in Portuguese). Retrieved 18 July 2014.

- "De Braga para o mundo, a PRIMAVERA da cidade". Alumni UMinho (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- "PRIMAVERA - Business Software Solutions SA". COTEC Portugal (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 3 March 2023.

- Aptiv (13 November 2019), Aptiv's Braga Technical Center, retrieved 16 January 2021

- "Politikprominenz bei Bosch: Bundeskanzlerin Merkel und Premier Costa eröffnen Tech Center in Portugal". Bosch Media Service (in German). Retrieved 16 January 2021.

- Sereno, Isabel; Dordio, Paulo (1994). SIPA (ed.). "21 Marcos Miliários (série Capela) Braga incerta via (v.PT01130700002)" (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA–Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Sereno, Isabel; Dordio, Paulo (1994), SIPA (ed.), Termas romanas de Maximinos/Alto da Cividade/Colina dos Maximinos (v.PT010303070040) (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico, retrieved 26 April 2012

- Sereno, Isabel; Leão, Miguel; Basto, Sónia (2010). SIPA (ed.). "Arco da Porta Nova/Arco da Rua do Souto (v.PT01130700002)" (in Portuguese). Lisbon: SIPA–Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Sereno, Isabel; Santos, João (1994), SIPA (ed.), Pelourinho de Braga (IPA.00000207/PT010303520013) (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico, archived from the original on 21 August 2016, retrieved 15 August 2016

- Sereno, Isabel; Dordio, Paulo; Gonçalves, Joaquim (2007). SIPA (ed.). "Castelo de Braga, designadamente a Torre de Menagem (restos)" (in Portuguese). Lisbon: SIPA–Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico. Archived from the original on 12 November 2013. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Sereno, Isabel; Santos, João (1994). SIPA (ed.). "Capela de Nossa Senhora da Conceição/Capela dos Coimbras/Capela do Senhor Morto" (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA –Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Sereno, Isabel; Dordio, Paulo; Gonçalves, Joaquim (2004). SIPA (ed.). "Capela de São Frutuoso de Montélios/Capela de São Salvador de Montélios" (in Portuguese). Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- "Portugal". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 9 July 2019.

- "Geminações". cm-braga.pt (in Portuguese). Braga. Archived from the original on 14 March 2016. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

Bibliography

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 4 (11th ed.). 1911. pp. 375–376.

.jpg.webp)