Cervical fracture

A cervical fracture, commonly called a broken neck, is a fracture of any of the seven cervical vertebrae in the neck. Examples of common causes in humans are traffic collisions and diving into shallow water. Abnormal movement of neck bones or pieces of bone can cause a spinal cord injury, resulting in loss of sensation, paralysis, or usually death soon thereafter (~1 min.), primarily via compromising neurological supply to the respiratory muscles as well as innervation to the heart.

| Cervical fracture | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Broken neck |

| |

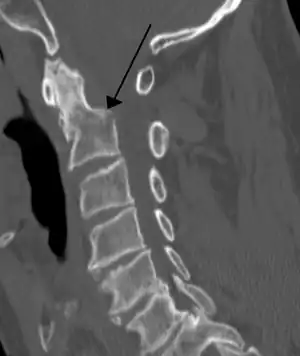

| A fracture of the base of the dens (a part of C2) as seen on CT. | |

| Specialty | Emergency medicine, neurosurgery, orthopedic surgery |

Causes

Considerable force is needed to cause a cervical fracture. Vehicle collisions and falls are common causes. A severe, sudden twist to the neck or a severe blow to the head or neck area can cause a cervical fracture.

Although high energy trauma is often associated with cervical fractures in the younger population, low energy trauma is more common in the geriatric population. In a study from Norway the most common cause was falls and the relative incidence of CS-fx increased significantly with age.[1]

Sports that involve violent physical contact carry a risk of cervical fracture, including American football, association football (especially the goalkeeper), ice hockey, rugby, and wrestling. Spearing an opponent in football or rugby, for instance, can cause a broken neck. Cervical fractures may also be seen in some non-contact sports, such as gymnastics, skiing, diving, surfing, powerlifting, equestrianism, mountain biking, and motor racing.

Certain penetrating neck injuries can also cause cervical fracture which can also cause internal bleeding among other complications.

Execution by hanging is intended to cause a fatal cervical fracture. The knot in the noose is placed to the left of the condemned, so that at the end of the drop, the head is jolted sharply upwards and to the right. The force breaks the neck, causing an immediate loss of consciousness and death within a few minutes.

Diagnosis

Physical examination

A medical history and physical examination can be sufficient in clearing the cervical spine. Notable clinical prediction rules to determine which patients need medical imaging are Canadian C-spine rule and the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS).[2]

Choice of medical imaging

- In children, a CT scan of the neck is indicated in more severe cases such as neurologic deficits, whereas X-ray is preferable in milder cases, by both US[3] and UK[4] guidelines. Swedish guidelines recommend CT rather than X-ray in all children over the age of 5.[5]

- In adults, UK guidelines are largely similar as in children.[4] US guidelines, on the other hand, recommend CT in all cases where medical imaging is indicated, and that X-ray is only acceptable where CT is not readily available.[6]

Radiographic detection

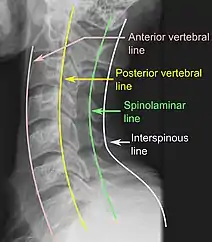

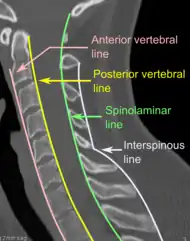

On CT scan or X-ray, a cervical fracture may be directly visualized. In addition, indirect signs of injury by the vertebral column are incongruities of the vertebral lines,[7] and/or increased thickness of the prevertebral space:[8]

X-ray of normal congruous vertebral lines

X-ray of normal congruous vertebral lines

Classification

There are proper names for several types of cervical fractures, including:

- Fracture of C1, including Jefferson fracture

- Fracture of C2, including Hangman's fracture

- Flexion teardrop fracture – a fracture of the anteroinferior aspect of a cervical vertebra

The AO Foundation has developed a descriptive system for cervical fractures, the AOSpine subaxial cervical spine fracture classification system.[9]

Surgery indication

The indication to surgically stabilize a cervical fracture can be estimated from the Subaxial Injury Classification (SLIC). In this system, a score of 3 or less indicates that conservative management is appropriate, a score of 5 or more indicates that surgery is needed, and a score of 4 is equivocal.[10] The score is the sum from 3 different categories: morphology, discs and ligaments, and neurology:[10]

| Points | |

|---|---|

| Morphology | |

| No abnormality | 0 |

| Vertebral compression | 1 |

| Burst | +1 (=2) |

| Distraction (facet joint perch, hyperextension) | 3 |

| Rotation / translation (facet joint dislocation, unstable teardrop, advanced flexion-compression | 4 |

| Discs and ligaments | |

| Intact | 0 |

| Indeterminate (isolated widening between spinous processes, magnetic resonance change) | 1 |

| Disrupted (widened disc space, facet perch, dislocation) | 2 |

| Neurology | |

| No neurological symptoms | 0 |

| Damaged nerve root | 1 |

| Complete spinal cord injury | 2 |

| Incomplete spinal cord injury (risk of worsening without surgery) | 3 |

| Continuous cord compression with neurological deficit | +1 |

Treatment

Complete immobilization of the head and neck should be done as early as possible and before moving the patient. Immobilization should remain in place until movement of the head and neck is proven safe. In the presence of severe head trauma, cervical fracture must be presumed until ruled out. Immobilization is imperative to minimize or prevent further spinal cord injury. The only exceptions are when there is imminent danger from an external cause, such as becoming trapped in a burning building.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as Aspirin or Ibuprofen, are contraindicated because they interfere with bone healing. Paracetamol is a better option. Patients with cervical fractures will likely be prescribed medication for pain control.

In the long term, physical therapy will be given to build strength in the muscles of the neck to increase stability and better protect the cervical spine.

Collars, traction and surgery can be used to immobilize and stabilize the neck after a cervical fracture.

Cervical collar

Minor fractures can be immobilized with a cervical collar without need for traction or surgery. A soft collar is fairly flexible and is the least limiting but can carry a high risk of further neck damage in patients with osteoporosis. It can be used for minor injuries or after healing has allowed the neck to become more stable.

A range of manufactured rigid collars are also used, usually comprising a firm plastic bi-valved shell secured with Velcro straps and removable padded liners. The most frequently prescribed are the Aspen, Malibu, Miami J, and Philadelphia collars. All these can be used with additional chest and head extension pieces to increase stability.

Rigid braces

Rigid braces that support the head and chest are also prescribed.[11] Examples include the Sterno-Occipital Mandibular Immobilization Device (SOMI), Lerman Minerva and Yale types. Special patients, such as very young children or non-cooperative adults, are sometimes still immobilized in medical plaster of paris casts, such as the Minerva cast.

Traction

Traction can be applied by free weights on a pulley or a halo type brace. The halo brace is the most rigid cervical brace, used when limiting motion to the minimum that is essential, especially with unstable cervical fractures. It can provide stability and support during the time (typically 8–12 weeks) needed for the cervical bones to heal.

Surgery

Surgery may be needed to stabilize the neck and relieve pressure on the spinal cord. A variety of surgeries are available depending on the injury. Surgery to remove a damaged intervertebral disc may be done to relieve pressure on the spinal cord. The discs are cushions between the vertebrae. After the disc is removed, the vertebrae may be fused together to provide stability. Metal plates, screws, or wires may be needed to hold vertebrae or pieces in place.

History

Arab physician and surgeon Ibn al-Quff (d. 1286 CE) described a treatment of cervical fractures through the oral route in his book Kitab al-ʿUmda fı Ṣinaʿa al-Jiraḥa (Book of Basics in the Art of Surgery).[12]

References

- Fredø HL, Rizvi SA, Lied B, Rønning P, Helseth E (December 2012). "The epidemiology of traumatic cervical spine fractures: a prospective population study from Norway". Scandinavian Journal of Trauma, Resuscitation and Emergency Medicine. 20 (1): 85. doi:10.1186/1757-7241-20-85. PMC 3546896. PMID 23259662.

- Saragiotto BT, Maher CG, Lin CW, Verhagen AP, Goergen S, Michaleff ZA (2018). "Canadian C-spine rule and the National Emergency X-Radiography Utilization Study (NEXUS) for detecting clinically important cervical spine injury following blunt trauma" (PDF). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (4): CD012989. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012989. hdl:10453/128267. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6494628.

- Julie C Leonard (2018-02-12). "Evaluation and acute management of cervical spine injuries in children and adolescents". UpToDate.

- "Head injury: assessment and early management". National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 2014. Updated in June 2017

- "Traumamanual". Region Skåne. Last updated: 2018-03-29

- Amy Kaji, Robert S Hockberger (2018-05-24). "Evaluation and acute management of cervical spinal column injuries in adults".

- Raniga SB, Menon V, Al Muzahmi KS, Butt S (June 2014). "MDCT of acute subaxial cervical spine trauma: a mechanism-based approach". Insights into Imaging. 5 (3): 321–338. doi:10.1007/s13244-014-0311-y. PMC 4035495. PMID 24554380.

- Rojas CA, Vermess D, Bertozzi JC, Whitlow J, Guidi C, Martinez CR (January 2009). "Normal thickness and appearance of the prevertebral soft tissues on multidetector CT". AJNR. American Journal of Neuroradiology. 30 (1): 136–141. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A1307. PMC 7051716. PMID 19001541.

- "Classification". AO Foundation. Retrieved 2019-05-08.

- Page 94 and Page 126 in: Douglas L. Brockmeyer, Andrew T. Dailey (2016). Adult and Pediatric Spine Trauma, An Issue of Neurosurgery Clinics of North America. Vol. 28. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323482844.

- Shantanu S Kulkarni, DO and Robert H Meier III, "Spinal Orthotics", Medscape Reference.

- Aciduman A, Belen D (December 2018). "An Early Description of Using Oral Route for the Management of Cervical Vertebra Fracture by Ibn al-Quff in the Thirteenth Century". World Neurosurgery. 120: 476–484. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2018.09.005. PMID 30205224. S2CID 52187620.

External links

- Van Waes OJ, Cheriex KC, Navsaria PH, van Riet PA, Nicol AJ, Vermeulen J (January 2012). "Management of penetrating neck injuries". The British Journal of Surgery. 99 (Suppl 1): 149–154. doi:10.1002/bjs.7733. hdl:1765/37154. PMID 22441870. S2CID 205512500.