Buckland Anglo-Saxon cemetery

Buckland Anglo-Saxon cemetery was a place of burial. It is located on Long Hill in the town of Dover in Kent, South East England. Belonging to the Anglo-Saxon period, it was part of the much wider tradition of burial in Early Anglo-Saxon England.

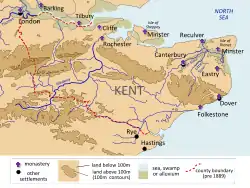

Location within Kent | |

| Location | Dover, Kent |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51.139792°N 1.300710°E |

| Type | Anglo-Saxon inhumation cemetery |

Buckland was an inhumation-only cemetery, with no evidence of cremation. The cemetery was on a false crest on the hill, having wide views of the surrounding landscape. Many of the dead were interred with grave goods, which included personal ornaments, weapons, and domestic items.

The cemetery was discovered in 1951 when the site was being developed into a housing estate. At the order of the Inspectorate of Ancient Monuments, archaeologists under the directorship of Vera I. Evison undertook a rescue excavation. Post-excavation work took three decades, while the artefacts went on display at the British Museum in Bloomsbury, Central London.

Location

The cemetery is located on the southern slope of Long Hill, on the eastern bank of the River Dour.[1] The site is visible from the river valley coming from the coast line.[1] Geologically, the base rock was unbroken solid chalk.[1]

A late prehistoric barrow ditch was located in the highest part of the Anglo-Saxon cemetery, on a false crest of the hill. There was also evidence for Romano-British activity on the site, with a small circular pit 2 feet deep cut into the chalk, containing a few sherds of Roman-era pottery.[2]

Archaeological investigation

In 1951, construction began on the Buckland Estate, a housing project on the site of the cemetery. Workmen uncovered a number of artefacts when they began clearing the soil, before coming across skeletal remains. The archaeologist W.P.B. Stebbing was brought in to examine the finds, and he oversaw the excavation of Grave C, revealing that it was of Anglo-Saxon date. The artefacts uncovered were sent to F.L. Warner, curator of Dover Museum, and the Inspectorate of Ancient Monuments decided to implement a rescue excavation of the site.[1] Excavation began in September 1951, under the directorship of Vera I. Evison, who was assisted by John Anstee, David Smith, and G.C. Dunning, who was responsible for surveying the site.[1] Due to the disturbance of the heavy machinery driving up the hill coupled with heavy rainstorms, four of the graves that had been identified – 31, 47, 51, and 86 – were destroyed prior to excavation.[3]

A lack of resources following the culmination of the Second World War meant that post-excavation work was delayed, and in 1963, the artefacts were transferred to the British Museum in Bloomsbury, Central London.[1] From 1974 to 1980, the Museum exhibited most of the finds from the site in their Medieval Gallery, while the final excavation report was finished in 1984, seeing publication in 1987.[1] Archaeologist Keith Parfitt later described the report as "a major contribution" to Kentish and wider Anglo-Saxon studies.[4]

In early 1994, proposals were put forward to construct another housing estate – termed "Castle View" – this time on the lower slopes of Long Hill. Kent County Council's Heritage Conservation Group requested that archaeologists put in some evaluation trenches in Castle View to see if any outlying Anglo-Saxon graves would be destroyed by the development; undertaking the work in a single day in March 1994, South-Eastern Archaeological Services revealed 12 graves. Realising that a full excavation was required, the developer, Orbit Housing Association, contracted the work to the Canterbury Archaeological Trust, who undertook the work from June to September.[5] Following the excavation, the developer donated all of the artefacts to the British Museum,[5] while the two roads serving the newly built houses were named Evison Close and Parfitt Way after the archaeologists who had led the two excavations.[6]

Background

With the advent of the Anglo-Saxon period in the fifth century CE, the area that became Kent underwent a radical transformation on a political, social, and physical level.[7] In the preceding era of Roman Britain, the area had been administered as the civitas of Cantiaci, a part of the Roman Empire, but following the collapse of Roman rule in 410 CE, many signs of Romano-British society began to disappear, replaced by those of the ascendant Anglo-Saxon culture.[7] Later Anglo-Saxon accounts attribute this change to the widescale invasion of Germanic language tribes from northern Europe, namely the Angles, Saxons, and Jutes.[8] Archaeological and toponymic evidence shows that there was a great deal of syncretism, with Anglo-Saxon culture interacting and mixing with the Romano-British culture.[9]

The Old English term Kent first appears in the Anglo-Saxon period, and was based on the earlier Celtic-language name Cantii.[10] Initially applied only to the area east of the River Medway, by the end of the sixth century it also referred to areas to the west of it.[10] The Kingdom of Kent was the first recorded Anglo-Saxon kingdom to appear in the historical record,[11] and by the end of the sixth century, it had become a significant political power, exercising hegemony over large parts of southern and eastern Britain.[7] At the time, Kent had strong trade links with Francia, while the Kentish royal family married members of Francia's Merovingian dynasty, who were already Christian.[12] Kentish King Æthelberht was the overlord of various neighbouring kingdoms when he converted to Christianity in the early seventh century as a result of Augustine of Canterbury and the Gregorian mission, who had been sent by Pope Gregory to replace England's pagan beliefs with Christianity.[13] It was in this context that the Finglesham cemetery was in use.

Kent has a wealth of Early Medieval funerary archaeology.[14] The earliest excavation of Anglo-Saxon Kentish graves was in the 17th century, when antiquarians took an increasing interest in the material remains of the period.[15] In the ensuing centuries, antiquarian interest gave way to more methodical archaeological investigation, and prominent archaeologists like Bryan Faussett, James Douglas, Cecil Brent, George Payne, and Charles Roach Smith "dominated" archaeological research in Kent.[15]

Cemetery features

Most of the graves at Buckland are orientated W-NW to E-SE.[16] Only one is facing the complete opposite direction.[16] The depth of the graves varied, although most were around 0.36 metres deep below the 1950s soil level. The deepest was 0.76 m (2 ft 6 in) below, while the shallowest were 15–23 cm (5.9–9.1 in) below the modern surface, indicating that the Anglo-Saxon ground level was undoubtedly higher.[16] The sizes of the graves also varied, with the smallest being 1.02 m × 0.51 m × 0.28 m (3 ft 4 in × 1 ft 8 in × 11 in), and the largest being 3.2 m × 0.86 m × 0.41 m (10.5 ft × 2.8 ft × 1.3 ft).[17] Excavators also noted that the quality of the grave cut had also differed, from those that were neatly and sharply cut, to those which had been more roughly cut into the rock.[18]

The conditions of the soil meant that the skeletal remains were not well preserved when excavated.[19] There were 11 instances where the osteological sexing of the bones differs from the gender of the grave goods; the excavators believed that the grave goods were an accurate indication of the individual's sex, and that the osteoarchaeology was incorrect.[20]

One of the most notable inhumations was found in Grave 67, and consisted of a female body that faced downward, while the skull was turned around to look up. The right arm was under the body but with the hand over the left shoulder, while the left arm was bent under the body. The right leg was bent under the extended left leg. The director of the excavation, Vera Evison, suggested that while the body could have simply been "unceremoniously" placed into the grave, the lack of grave goods made her suspect that the woman had been buried alive, with her position indicative of an attempt to push herself out of the grave.[19]

Another notable case was Grave 96, the only double burial, containing one man aged around 40, and one person of indeterminate sex aged between 20 and 30; both were given the typical weapon burials associated with male burials. Evison suggested that it might indicate that homosexuality was "sufficiently socially acceptable" that two male lovers were buried together.[21]

Archaeogenetic research on a large sample of skeletons from the cemetery showed that most were identical to a reference group of Continental northern European (CNE) DNA samples when compared with a Welsh/British/Irish (WBI) reference group that showed genetic continuity from Britain's Iron-Age population. Influence of WBI genetic material was, however, traceable in some detail. The researchers gave the example of

a group of relatives, spanning at least three generations, who all exhibit unadmixed CNE ancestry. Down the pedigree, we then see the integration of a female into this group, who herself had unadmixed WBI ancestry (grave 304), and two daughters (graves 290 and 426), consequently of mixed ancestry. WBI ancestry entered again one generation later, as visible in near 50:50 mixed-ancestry grandchildren (graves 414, 305 and 425). Grave goods, including brooches and weapons, are in fact found on both sides of this family tree, pre-mixing and post-mixing (for example, in the youngest and mixed generation, we found both weapons, beads and pin, and their mother with a brooch).

Adding in a third reference group, people from the Iron Age in present-day France, the researchers found more specifically that about half the genetic material matched the CNE profile, a quarter the WBI profile, and a quarter the western European profile, indicating that many of the people buried had ancestry in that region.[22]

See also

References

Footnotes

- Evison 1987, p. 11.

- Evison 1987, pp. 13–15.

- Evison 1987, p. 13.

- Parfitt 2012, p. 6.

- Parfitt 2012, p. 1.

- Parfitt 2012, p. 8.

- Welch 2007, p. 189.

- Blair 2000, p. 3.

- Blair 2000, p. 4.

- Welch 2007, pp. 189–190.

- Brookes & Harrington 2010, p. 8.

- Welch 2007, pp. 191–192.

- Welch 2007, pp. 190–191.

- Brookes & Harrington 2010, p. 14.

- Brookes & Harrington 2010, p. 15.

- Evison 1987, p. 16.

- Evison 1987, pp. 16–17.

- Evison 1987, p. 17.

- Evison 1987, p. 18.

- Evison 1987, p. 125.

- Evison 1987, p. 126.

- Gretzinger, J., Sayer, D., Justeau, P. et al. The Anglo-Saxon migration and the formation of the early English gene pool. Nature 610, 112–119 (2022). doi:10.1038/s41586-022-05247-2.

Bibliography

- Blair, John (2000). The Anglo-Saxon Age: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0192854032.

- Brookes, Stuart; Harrington, Sue (2010). The Kingdom and People of Kent AD 400–1066. Stroud: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-5694-2.

- Evison, Vera I. (1987). Dover: The Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery. London: Historic Buildings and Monuments Commission for England. ISBN 1-85074-090-9.

- Parfitt, Keith; Anderson, Trevor (2012). Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery, Dover: Excavations 1994. Canterbury: Canterbury Archaeological Trust.

- Parfitt, Keith (2012). "Introduction and Archaeological Background". Buckland Anglo-Saxon Cemetery, Dover: Excavations 1994. Canterbury: Canterbury Archaeological Trust. pp. 1–8.

- Welch, Martin (2007). "Anglo-Saxon Kent to AD 800". In J.H. Williams (ed.). The Archaeology of Kent to AD 800. Rochester: Kent County Council. pp. 187–250.