Buncrana

Buncrana (/ˈbʌnkrænə/ bun-KRA-NA; Irish: Bun Cranncha, meaning 'foot of the (River) Crana') is a town in County Donegal, Ireland. It is beside Lough Swilly on the Inishowen peninsula, 23 kilometres (14 mi) northwest of Derry and 43 kilometres (27 mi) north of Letterkenny.[3] In the 2022 census, the population was 6,971,[1] making it the second most populous town in County Donegal, after Letterkenny, and the largest in Inishowen.

Buncrana

Bun Cranncha | |

|---|---|

Town | |

Buncrana from the south | |

Coat of arms | |

| Motto(s): Aoibhinn Linn Áille na hÁite Seo (Irish) "sweet to us is the beauty of this place" | |

Buncrana Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 55.1364°N 7.4560°W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Ulster |

| County | Donegal |

| Dáil Éireann | Donegal |

| EU Parliament | Midlands–North-West |

| Elevation | 62 m (203 ft) |

| Population | 6,971 |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (IST) |

| Eircode routing key | F93 |

| Telephone area code | +353(0)74 |

| Irish Grid Reference | C346320 |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1821 | 198 | — |

| 1831 | 1,059 | +434.8% |

| 1841 | 961 | −9.3% |

| 1851 | 797 | −17.1% |

| 1861 | 686 | −13.9% |

| 1871 | 755 | +10.1% |

| 1881 | 764 | +1.2% |

| 1891 | 735 | −3.8% |

| 1901 | 1,316 | +79.0% |

| 1911 | 1,848 | +40.4% |

| 1926 | 2,309 | +24.9% |

| 1936 | 2,295 | −0.6% |

| 1946 | 2,729 | +18.9% |

| 1951 | 3,039 | +11.4% |

| 1956 | 3,064 | +0.8% |

| 1961 | 3,165 | +3.3% |

| 1966 | 3,115 | −1.6% |

| 1971 | 3,334 | +7.0% |

| 1981 | 3,938 | +18.1% |

| 1986 | 4,131 | +4.9% |

| 1991 | 4,388 | +6.2% |

| 1996 | 4,805 | +9.5% |

| 2002 | 5,271 | +9.7% |

| 2006 | 5,911 | +12.1% |

| 2011 | 6,839 | +15.7% |

| 2016 | 6,785 | −0.8% |

| 2022 | 6,971 | +2.7% |

| [1][2] | ||

Buncrana is the historic home of the O'Doherty clan and originally developed around the defensive tower known as O'Doherty's Keep at the mouth of the River Crana. The town moved to its present location just south of the River Crana when George Vaughan built the main street in 1718.

The town was a major centre for the textile industry in County Donegal from the 19th century until the mid-2000s (decade).

History

O'Doherty's Keep

On the northern bank of the River Crana as it enters Lough Swilly sits the three-storey O'Doherty's Keep, which is the only surviving part of an original 14th-century Norman castle. The first two levels of the keep were built after 1333.[4][5] In 1601 the O'Doherty's Keep was described as being a small, two-storey castle, inhabited by Conor McGarret O'Doherty. In 1602 the third level was added and it was upgraded by Hugh Boy O'Doherty as an intended base for Spanish military aid that hoped to land at Inch.[5]

The keep was burned by Crown forces in 1608 in reprisal for the rebellion of Sir Cahir O'Doherty, who had sacked and razed the city of Derry. After Sir Cahir O'Doherty was killed at the Battle of Kilmacrennan, he was attaindered and his land seized. The keep was granted to Sir Arthur Chichester, who then leased it to Englishman Henry Vaughan, where it was repaired and lived in by the Vaughan family until 1718.[6]

In 1718, Buncrana Castle was built by George Vaughan, it was one of the first big manor houses built in Inishowen, and stone was taken from the bawn, or defensive wall, surrounding O'Doherty's Keep to build it. It was erected on the original site of Buncrana, which had grown up in the shadow of the keep. Vaughan moved the town to its present location, where he founded the current main street and built the Castle Bridge (a six-arched stone single lane bridge) across the River Crana leading to his Castle.[7]

During the 1798 Rebellion, Theobald Wolfe Tone was held in Buncrana Castle when he was captured after the British/French naval battle off the coast of Donegal, before being taken to Derry and then subsequently to Dublin. On 18 May 1812, Isaac Todd bought the entire town of Buncrana, also the townlands of Tullydish, Adaravan and Ballymacarry, at the Court of Chancery on behalf of the trustees of the Marquess of Donegall. His nephews inherited the castles, and they later became known as the Thornton-Todds. The castle remains as a private home today. In the forecourt there is a memorial rock in honour of Sir Cahir O'Doherty, and a plaque dedicated to Wolfe Tone.[8]

One of the oldest remaining inhabited residences in Buncrana is a Georgian property called Westbrook House, situated at the entrance to Swan Park just north of the town centre of Buncrana. The house was built in 1807 by Judge Wilson, who also built the single-arch stone bridge (referred to as Wilson's Bridge) leading to the house and the entrance to Swan Park.

19th century

The town was often the focal point for unrest in the surrounding areas as rural peasants protested against evictions and rent increases. In 1834, unrest broke out when local residents tried to expel various landlord agents from the area. The names of individual agents were posted on the church doors in Buncrana by a "Captain Wright" warning that the agents risked death if they continued to live in the area. The unrest forced the administration in Dublin Castle to station troops in the towns of Buncrana, Clonmany and Carndonagh.[9]

Communal relations between Protestant and Catholic communities were tense and on occasions led to violence. In November 1833, communal tensions broke out. The houses of local Protestants were attacked and the windows of their houses were smashed.[10]

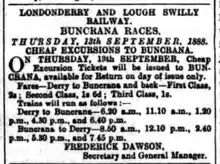

During the second half of the 19th century, the town developed a significant tourism industry. Tourists, particularly from Derry, were able to access the town through the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway.[11]

20th century

In October 1905, Buncrana was the first town in County Donegal to receive electricity. It was generated at Swan Mill which continued to provide electricity for the town until September 1954 when Buncrana was brought under the ESB Rural Electrification Scheme.[7]

On 30 July 1922, during the Irish Civil War, Buncrana was captured by the Free State forces from Republican forces without the loss of life. The Free State forces held the railway station, telephone and telegraph offices and all the roads entering the town. At 4:00am a sentry stopped a car on the outskirts of the town and on discovering it contained the Republican commander, with five armed volunteers, arrested them. At around 7:00am the Republican forces' position was surrounded and were given fifteen minutes to surrender. They complied, were arrested and their weapons and ammunition seized. Later that day, 100 Free State troops commandeered a train at Buncrana station and proceeded to take Clonmany, Carndonagh and other locations on the peninsula.[12]

Buncrana was the object of public attention in 1972, when after Operation Motorman it became the place of refuge for many Provisional Irish Republican Army members from Derry. In 1991, a local Sinn Féin councillor, Eddie Fullerton, was murdered by loyalists from Northern Ireland.[13]

In March 2016, Buncrana came to public attention when five people of the same family died after their car slipped off Buncrana Pier into the waters of Lough Swilly. Only a 4-month-old baby girl survived when the driver, Sean McGrotty, passed his daughter through a window to a passer-by who swam out to help.[14][15][16][17][18] On 23 November 2017 an inquest found that McGrotty died by 'misadventure', as the post-mortem results showed that he was more than three times over the drink drive limit.[19]

Politics

Local

Buncrana Town Council was the Local Authority for the town and provided an extensive range of services in the area. These services ranged from planning control, the provision of social housing, the upkeep and improvement of roads, and the maintenance of parks, beaches and public open spaces. The Town Council was abolished in June 2014 when the Local Government Reform Act 2014 was implemented.[20] Its functions were taken over by Donegal County Council in 2014. Buncrana is in the Inishowen Municipal District, which elects councillors to Donegal County Council.[21]

National

Buncrana is part of the Donegal (Dáil constituency) since 2016. Previously it was part of the Donegal North-East constituency of Dáil Éireann.

Geography

Buncrana is located on the eastern shore of Lough Swilly in north County Donegal. The main urban area of the town is situated between the Crana River to the north and the Mill River to the south. The principal street follows a rough north–south route and is divided into Upper and Lower Main Street by Market Square. The Main Street has a one-way traffic system. The River Crana is crossed by four bridges: Castle Bridge (which gives vehicular access to Buncrana Castle and pedestrian access to Swan Park), Westbrook Bridge (officially, Wilson's Bridge), the new Cockhill Bridge (officially opened in 2018[22]) and the old Cockhill Bridge (now a pedestrian bridge). The Mill River, south of the town, is crossed by two bridges: Victoria Bridge (known locally as the Iron Bridge) which is the main point of access to the town and the Mill Bridge which is at the end of the Mill Brae road at the south end of the town.

Geology

The underlying bedrock includes Fahan slate formation. The river valley of the Mill River flows over a narrow band of Culdaff limestone with a sill of metadolerite along the river's southern embankment extending from the estuarine zone inland. Sandy gravels and conglomerates overlie bedrock. The geology was formed during the Lower Carboniferous Period. The local soils throughout the area range from shallow to moderate depth peaty podzols and established podzolic types with a moderate percentage of loam and sandy clays.

Climate

Buncrana, like the rest of Ireland, has a temperate oceanic climate, or Cfb on the Köppen climate classification system, characterised by cool summers and mild winters.[23] Ireland's position in the Atlantic Ocean means that its climate is strongly influenced by the Gulf Stream, which keeps it a few degrees warmer than other locations at the same latitude.

These are the average temperature and rainfall figures between 1961 and 1990 taken at the Met Éireann weather station at Malin Head, about 35 kilometres (22 mi) northwest of Buncrana:

| Climate data for Malin Head (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) |

7.5 (45.5) |

8.7 (47.7) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.7 (54.9) |

15.0 (59.0) |

16.2 (61.2) |

16.6 (61.9) |

15.3 (59.5) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.8 (49.6) |

8.4 (47.1) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

3.7 (38.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

9.6 (49.3) |

11.4 (52.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

10.1 (50.2) |

8.3 (46.9) |

5.2 (41.4) |

4.2 (39.6) |

6.8 (44.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 114.2 (4.50) |

76.6 (3.02) |

86.5 (3.41) |

57.5 (2.26) |

58.9 (2.32) |

65.0 (2.56) |

71.8 (2.83) |

91.6 (3.61) |

102.1 (4.02) |

118.7 (4.67) |

114.7 (4.52) |

102.9 (4.05) |

1,060.5 (41.77) |

| Source: Met Éireann[24] | |||||||||||||

Transport

Buncrana railway station opened on 9 September 1864, was closed for passenger traffic on 6 September 1948, and finally closed altogether on 10 August 1953.[25]

The nearest railway station is operated by Northern Ireland Railways and runs from Londonderry railway station via Coleraine to Belfast Central railway station and Belfast Great Victoria Street railway station. The strategically important Belfast-Derry railway line is to be upgraded to facilitate more frequent trains and improvements to the permanent way such as track and signalling to enable faster services.[26]

Buncrana is connected to the rest of the national road network via a regional road, the R238. This connects it to the N13, the national primary road that connects Letterkenny and Derry (it becomes the A2 when it crosses the border). The town is considered the gateway to Inishowen and lies on the "Inishowen 100", an approximate 100-mile route around the peninsula that passes various scenic sites.

TFI Local Link routes 242 (Redcastle/Buncrana),[27] 252 (Burt/Buncrana),[28] 995 (Muff/Buncrana)[29] and 995A (Illies/Buncrana)[30] all service the town.

Local bus company McGonagle Bus and Coach operates an hourly bus service from Derry to Buncrana and vice versa. The company took over the route from Lough Swilly Buses in April 2014 after Lough Swilly ceased trading.[31][32] The buses run every hour at ten minutes past the Hour, each way. The two routes serving the town are 951 (Malin/Carndonagh/Letterkenny)[33] and 956 (Cockhill/Buncrana/Derry). [34]

Demography

| Buncrana Compared[35] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 Irish census | Buncrana | County Donegal | Republic of Ireland |

| Total population | 6,839 | 161,137 | 4,581,269 |

| Foreign born | 28.8% | 22.1% | 16.9% |

| White or White Irish | 86.5% | 90.6% | 84.5% |

| Black or Black Irish | 0.3% | 0.6% | 1.4% |

| Asian or Asian Irish | 0.6% | 0.8% | 1.9% |

| Roman Catholic | 90.9% | 85.4% | 84.3% |

| No religion | 4.1% | 3.2% | 5.9% |

| Ability to speak Irish | 30.0% | 38.4% | 40.6% |

| Third level degree (NFQ level 7 or higher) | 19.0% | 18.2% | 20.5% |

The results of the 2022 census put the population of Buncrana at 6,971, its historical highest.[1]

At the same census, the town had 2,603 private households, 27.6% were made up of one person living alone, 15.8% were couples without children, 30.3% were couples with children, 12.6% were lone-parent families and 13.7% were classified under other categories. 3,403 were males and 3,568 females.

Around 81.7% of residents were recorded as Catholic, 5.0% were of another stated religion (e.g. Church of Ireland, Presbyterian, Orthodox or Islam). The percentage of residents with no religion was 9.2%.

27.6% of the town's residents were 'foreign-born'.

Of people aged 3 and over, 31.0% could speak Irish.

The percentage of people over the age of 15 whose full-time education had ceased who possessed a third-level degree (NFQ level 7 or higher) was 26.0%.

Tourism

Buncrana has a relatively strong tourism industry, and it is one of the most popular holiday destinations in the northwest of Ireland. This is possibly due to its close proximity to Derry, and also for its wide range of retail stores. It also has well-developed tourist facilities, and it serves as the main town on the Inishowen peninsula, which also helps with sustaining the tourism industry in the town.[36]

Lisfannon beach, a Blue Flag beach, sits on the shores of Lough Swilly just south of the town, and is an important recreational beach that is popular with locals and day-trippers from Derry.[37]

Sport

Buncrana is home to many sports clubs, including clubs for soccer, Gaelic football and hurling, athletics and watersports. Football clubs based around Buncrana include Buncrana Hearts F.C., Cockhill Celtic F.C. and Illies Celtic. Buncrana Hearts and Illies Celtic play in the Inishowen Football League and Cockhill Celtic play in the Ulster Senior League. Derry City F.C. currently play at Maginn Park, Buncrana.

Gaelic Football is also a popular sport in Buncrana, and the club caters for teams from Under-8 level right up to Senior level. They play their home games at the Scarvey, the team is very successful underage, winning at least two Inishowen titles the last few seasons and winning four county championships since 2000, reaching under-14 final for the past two seasons as well as the under 15s last season.

Buncrana Golf Club has the oldest 9-hole links course in Ireland.[38]

Culture

Three buildings in Buncrana are recorded on the Record of Protected Structures, namely the Drift Inn (formerly Buncrana Railway Station), Buncrana Castle and Swan Mill.[39]

Music

Buncrana's music scene is served by a number of local pubs and bars, which have live music several nights of the week. These include Roddens Bar, O Flaherty's and The Drift Inn, which have a mix of traditional, rock and country music. The annual Buncrana Music & Arts Festival takes place every 23 July in the town.[40]

The Buncrana Music and Arts Festival returned to the town in 2010, after a five-year absence. The festival included successful performances from The Coronas, The Undertones and Altan. It has recurred each year since.

Media

The two main local newspapers that serve the Inishowen area, the Inish Times and the Inishowen Independent, have their offices in Buncrana. Local issues in the town and peninsula are also covered in the Derry Journal. The local radio station is Highland Radio and it is based in Letterkenny.

Buncrana receives all the Irish national television and radio stations from the Saorview television network from the local Fanad television transmitter. Due to its close proximity to Derry, before the 2012 digital switchover, the town could receive the five main UK television channels from the Derry or Limavady television transmitters from the mid-1950s.

Community

Tidy Towns

In 2012, Buncrana won a silver medal in the national Tidy Towns Competition. The work of the Buncrana Lighthouse Restoration Project was also recognised when they received a Heritage Award.[41]

Youth facilities

Buncrana Youth Club is open seven days a week and provides various services such as arts, sports, drama, music and computers. It also operates summer camps and provides coaching, personal development and peer education.[42]

Buncrana Youth Drop in is located in the Plaza theatre on the Main Street and is usually open from 7pm til 10pm and provides a safe place for young people with such facilities as a pool table, internet access, TV, gaming consoles and a small shop. It also runs workshops and other youth projects.[43]

Buncrana Youth Club and Buncrana Drop in are both affiliated with Donegal Youth Service.

BreakOUT is a lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) youth organisation in County Donegal that has a local group in Buncrana. The group is open to ages from 14 to 23. The group has run various projects to promote LGBT causes in Buncrana. In 2011, positive slogans to combat homophobia were drawn on the Main Street footpath. The group meets at the Inishowen Development Partnership building on Saturdays from 7pm to 9pm.

Education

Buncrana is served by three secondary schools: Crana College, a vocational school managed by the Donegal Education and Training Board and Scoil Mhuire, Buncrana, a voluntary secondary school under the trusteeship of CEIST (Catholic Education Irish Schools Trust) and Coláiste Chineal Eoghain (an Irish language secondary school (Meanscoil) in Tullyarvan Mill). Crana College was set up in 1925, Scoil Mhuire in 1933 and Coláiste Chineál Eoghain in 2007.[44] As of September 2011, Crana College had 540[45] registered students, while Scoil Mhuire had around 700.[46] The town's has four primary schools: Scoil Íosagáin, Cockhill National School, St Mura's National School and Gaelscoil Bhun Cranncha.[47]

Buncrana Community Library opened in 2000 in a refurbished Presbyterian church. It won the Public Library Buildings Awards 2001 for the best small library in the converted, extended or refurbished category.[48]

People

- Ryan Bradley (Gaelic footballer), (1985 – present), 2012 All-Ireland Senior Football Championship Winner with Donegal

- Daniel Devlin, (1814 – 22 February 1867), prosperous businessman and City Chamberlain of New York City

- Hugh Doherty (footballer), (1921 – 29 September 2014), Professional Irish footballer (Celtic, Blackpool, Derry City and Dundalk)

- John Doherty, (1798–1854), radical trade unionist

- Eddie Fullerton, (1935 – 25 May 1991), Sinn Féin councillor assassinated by the Ulster Defence Association

- Danny Hutton, (born 10 September 1942), singer with Three Dog Night and head of Hanna-Barbera Records from 1965 – 1966

- Pádraig Mac Lochlainn, politician

- Ray McAnally, (30 March 1926 – 15 June 1989), actor whose filmography includes The Mission, My Left Foot, and A Very British Coup

- Michael McCorkell, (3 May 1925 – 13 November 2006), Lord Lieutenant of County Londonderry

- Frank McGuinness, (born 29 July 1953), playwright and poet whose work includes Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme

- Patrick Stone, (14 March 1854 – 23 December 1926), member of the Western Australian Legislative Assembly

- Mark Timlin, (17 November 1994 – Present), Professional footballer (Derry City and St Patrick's Athletic)

International relations

Twin towns – Sister cities

Buncrana is twinned with two towns. It twinned with Campbellsville, Kentucky as both towns had a large Fruit of the Loom plant. The plant was a large source of employment in Buncrana before it moved its operations overseas to Morocco.[49] Buncrana is twinned with the following towns:

| Town | Geographical location | Nation | Since |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campbellsville | Kentucky | 1991 | |

| Fréhel/Plévenon | Brittany | 2007 |

References

- "Interactive Data Visualisations: Towns: Buncrana". Census 2022. Central Statistics Office. Retrieved 26 September 2023.

- "CSO: Census: Census Home Page". Archived from the original on 20 September 2010. Retrieved 6 July 2012. and www.histpop.org. Post 1961 figures include environs of Buncrana. For a discussion on the accuracy of pre-famine census returns see J.J. Lee "On the accuracy of the pre-famine Irish censuses" in Irish Population, Economy and Society edited by JM Goldstrom and LA Clarkson (1981) p. 54, and also "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700–1850" by Joel Mokyr and Cormac Ó Gráda in The Economic History Review, New Series, Vol. 37, No. 4 (November , 1984), pp. 473–488.

- "Town information: location". buncrana.com. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- Archer, Lucy; Edwin Smith (1999). Architecture in Britain and Ireland, 600–1500. Harvill Press. ISBN 978-1-86046-701-1.

- Harbison, Peter (1975). Guide to the national monuments in the Republic of Ireland. Gill & Macmillan. ISBN 9780717107582.

- Lewis, Samuel; Edwin Smith (1837). A Topological Dictionary of Ireland vol.1.

- "Chronology of local history". Buncrana Town Council (visitbuncrana.com). Archived from the original on 25 November 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- "Local history". Buncrana Town Council (visitbuncrana.com). Archived from the original on 26 November 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- "The State of Ennisowen". Londonderry Sentinel. 4 October 1834.

- "Disgraceful outrage in Buncrana". Westmeath Journal. 28 November 1833.

- "Cheap Excursions to Buncrana". Londonderry Sentinel. 11 September 1888.

- "REBELS ARE ROUTED IN DONEGAL TOWNS; Free State Troops Capture Gar- risons at Letterkenney, Buncrana and Cardonagh. ENDS BRIGANDAGE THERE Raiders Had Terrorized the District for Weeks, Frequently Holding Up Trains" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 July 1922.

- "Eddie Fullerton murder probe". Derry Journal. Archived from the original on 14 June 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- "Five die in Donegal pier tragedy". BBC News. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- McDaid, Laura (23 March 2016). "Man's 'near miss' at pier tragedy scene". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 January 2018. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- "Buncrana pier deaths: Adults and children 'were from Derry'". 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- "Buncrana pier deaths: 'The man was still shouting to me when the car went down'". The Irish Times. Archived from the original on 26 September 2020. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Final moments recalled in Buncrana tragedy". RTÉ News. 21 March 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- "Buncrana pier victim's partner says tragedy was 'accident waiting to happen'". Belfast Telegraph. Belfast Telegraph. 23 November 2017. Archived from the original on 16 November 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "Local Government Reform Act 2014" (PDF). Irish Statute Book.

- "Councillors for the Municipal District of Inishowen". Donegal County Council. 3 March 2016. Archived from the original on 15 March 2016. Retrieved 3 March 2016.

- "Buncrana Youth Club". Donegal County Council. Archived from the original on 16 February 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2019.

- Peel, M. C.; Finlayson B. L.; McMahon, T. A. (2007). "Updated world map of the Köppen–Geiger climate classification". Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 11 (5): 1633–1644. Bibcode:2007HESS...11.1633P. doi:10.5194/hess-11-1633-2007. ISSN 1027-5606. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 14 October 2011. (direct: Final Revised Paper Archived 29 February 2012 at the Wayback Machine)

- "Malin Head, monthly and annual mean values (1961–1990)". Met Éireann. Archived from the original on 9 October 2011. Retrieved 13 October 2011.

- "Buncrana station" (PDF). Railscot – Irish Railways. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 13 September 2007.

- McDaid, Brendan (9 November 2011). "Derry rail upgrade right on track". The Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 14 December 2011. Retrieved 15 February 2012.

- "242-Redcastle-to-Buncrana-via-Inch-Fri-Only-scaled-1.jpg" (JPG). Local Link Donegal-Sligo-Leitrim. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- "252-Burt-to-Buncrana.jpg" (JPG). Local Link Donegal-Sligo-Leitrim. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- "995-Muff-Buncrana.jpg" (JPG). Local Link Donegal-Sligo-Leitrim. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- "995A-Illies-to-Buncrana.jpg" (JPG). Local Link Donegal-Sligo-Leitrim. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- "Buncrana Derry bus timetable -". Archived from the original on 6 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2014.

- "UPDATE: Ulsterbus to serve Muff-Derry route". 18 April 2014. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "Malin Cardonagh Letterkenny - Timetable". McGonagle Bus & Coach Hire. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- "Buncrana to Derry Bus - TimeTable". McGonagle Bus & Coach Hire. Retrieved 24 August 2023.

- "2011 Census results; Small Area Population Maps (SAPMAP)". Central Statistics Office. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- Team, City Travel Guide. "Buncrana travel guide — Buncrana tourism and travel information". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- "Awarded sites: Lisfannon beach". blueflag.org. Archived from the original on 30 September 2011. Retrieved 14 October 2011.

- "Buncrana Golf Club". Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- "Appendix 5 Environmental Report in respect of the Buncrana & Environs Development Plan 2008– 2015" (PDF). Buncrana and Environs Development Plan 2008 – 2014. Donegal County Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- "MrBuncrana James Townfestival - Facebook". Facebook. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- "Buncrana sparkles in Tidy Town awards". Inishowen News. 11 September 2012. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Buncrana Youth Club". Donegal Youth Service. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Buncrana Youth Drop In". Donegal Youth Service. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "Scoil Mhuire secondary school, Buncrana". CEIST. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- "A Brief History". Crana College. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 20 October 2011.

- "About The School". Scoil Mhuire, Buncrana. Archived from the original on 26 April 2012. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

- "Information: Education". Buncrana Town Council (buncrana.com). Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2011.

- "Buncrana Community Library". librarybuildings.ie. Archived from the original on 25 April 2012. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- Deegan, Gordon (25 October 2010). "Morocco transfer eats into Fruit of the Loom profits". Irish Independent. Archived from the original on 28 October 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2011.