Buoyant Billions

Buoyant Billions (1948) is a play by George Bernard Shaw. Written at the age of 92, it was his last full-length play. Subtitled "a comedy of no manners", the play is about a brash young man courting the daughter of an elderly billionaire, who is pondering how to dispose of his wealth after his death, a subject that was preoccupying Shaw himself at the time.

| Buoyant Billions | |

|---|---|

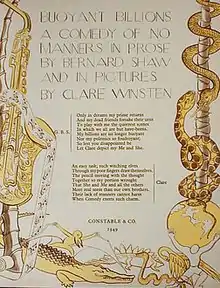

1949 edition with designs by Clare Winsten | |

| Written by | George Bernard Shaw |

| Date premiered | 21 October 1948 |

| Place premiered | Schauspielhaus Zürich |

| Original language | English |

| Subject | A billionaire's daughter meets a world betterer |

| Genre | comedy |

| Setting | Panama; London |

Creation

Shaw began work on the play in 1946, shortly after the end of World War II, but left it unfinished, returning to it in 1948. It was inspired by a painting of the Last Supper. Shaw had the idea that a man about to die would be surrounded by people giving him advice on how to dispose of his assets.[1] The play refers to recent political and scientific developments, notably the policies of the 1945–1950 Labour government and the invention of the atomic bomb.

Characters

- Junius

- His Father

- Clementina Buoyant

- Bayano

- The Chinese Priest

- Sir Ferdinand Flopper

- Tom Buoyant

- Eudoxia Emily

- Dick Buoyant

- Julia Buoyant

- Mrs. Harry

- Frederick

- Bastable "Bill" Buoyant

- Narrator

Plot

A young man and his wealthy father argue about the youth's future. The youth is excited by the new developments in science, believing that atomic energy can be a boon to mankind. He says he intends to become a "world betterer" and will travel the world to ponder his future. In Panama, he meets a young woman. After a sparring conversation, they fall in love; however, she is horrified by the thought of love, and returns home to London, declaring love to be a dangerous disease.

In London, the family of billionaire Bill Buoyant are debating how to hold on to his billions after his death, as they believe that the new Labour government will tax it away. They discuss the fact that Buoyant's oldest daughter is a black sheep, as she was born to their father's first wife before the family had money, and so behaves like a poor person, having learned to work. They were born to the more genteel second wife. The eldest daughter suddenly appears, declaring that she has returned from Panama to escape from love. Her lover soon arrives too, having followed her. He tells her frankly that he wants to marry her for her money, but is also unfortunately irresistibly attracted to her by "animal magnetism" and the "life force". The characters discuss the true nature of life, love and marriage. He convinces her that the money will be useful to pursue his schemes for making the world a better place. Impressed by his having thought this through, she eventually agrees to marry him once he convinces her that marriage need not be a form of slavery.

Bill Buoyant appears and blesses the couple, then consults with his lawyer about disposing of his billions. He decides to leave money to his eldest daughter and her soon-to-be husband, but nothing to the children of his second wife. The family, unaware of this, discuss their ideas, as the young couple are hastily married.

Production

Shaw originally intended that the play would be performed at the Festival Theatre, Malvern, but later decided to give the play its world première in Switzerland, in a German translation, because he believed that English critics were prejudiced against his recent work. Shaw's German translator Siegfried Trebitsch lived in Zürich, and Shaw discussed the translation in detail with him. The German version was entitled Zu viel Geld. Trebitsch had made it "more Germanically serious" in the words of Stanley Weintraub, and Shaw revised it drastically with the help of his assistant Fritz Loewenstein to reintroduce his characteristic light touch.[2]

It was played at the Schauspielhaus in Zürich on October 21, 1948. Critics were still unimpressed. Hans Guggenheim wrote that it was a "conversation-piece whose scanty action seems accidental and unconvincing.... Mr. Shaw could doubtless have written a spirited and amusing essay instead of this not very gripping play. We thought that the actors did their best to breathe some real life into the phantom-like figures of the play, and were amused by the fireworks of Shaw's bon mots, but not very much impressed, and the evening resulted in what someone called 'manifestation of respect.'"[3]

It was published in "an especially attractive edition" in Zürich.[1] A limited edition of Buoyant Billions was published in London in 1949, with illustrations by Shaw's neighbour Clare Winsten.[1]

References

- Archibald Henderson, George Bernard Shaw: Man of the Century, Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1956, pp. 664; 923.

- Weintraub, Stanley, Shaw's People, Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996, pp.204ff.

- Hans Guggenheim, "Letter to the Editor," John O'London's Weekly, LVII ( November 12, 1948), 546.