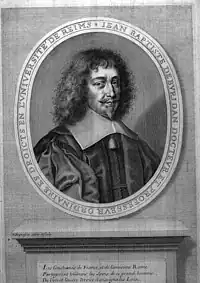

Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (French: [byʁidɑ̃]; Latin: Johannes Buridanus; c. 1301 – c. 1359/62) was an influential 14th‑century French philosopher.

Jean Buridan | |

|---|---|

| Born | c. 1301 |

| Died | c. 1359 – c. 1362 |

| Alma mater | |

| Era | Medieval philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

| Institutions | University of Paris |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas |

|

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and on the works of Aristotle. Buridan sowed the seeds of the Copernican Revolution in Europe.[1] He developed the concept of impetus, the first step toward the modern concept of inertia and an important development in the history of medieval science. His name is most familiar through the thought experiment known as Buridan's ass, but the thought experiment does not appear in his extant writings.

Life

Education and career

Buridan was born sometime before 1301, perhaps at or near the town of Béthune in Picardy, France,[2] or perhaps elsewhere in the diocese of Arras.[3] He received his education in Paris, first at the Collège du Cardinal Lemoine and then at the University of Paris, receiving his Master of Arts degree and formal license to teach at the latter by the mid-1320s.[2]

Unusually, he spent his entire academic life in the faculty of arts, rather than obtaining the doctorate in law, medicine or theology that typically prepared the way for a career in philosophy.[2] Also unusual for a philosopher of his time, Buridan further maintained his intellectual independence by remaining a secular cleric, rather than joining a religious order. A papal letter of 1330 refers to him as simply, "clericus Atrebatensis diocoesis, magister in artibus [a cleric from the Diocese of Arras and Master of Arts]."[4] As university statutes permitted only those educated in theology to teach or write on the subject, there are no writings from Buridan on either theological matters or commentary of Peter Lombard's Sentences.[2]

Speculation on his reasons for avoiding religious matters have remained uncertain.[5][6][7] Most scholars think it is unlikely that he went unnoticed, given his philosophical talents. As well, it is unlikely that he could not afford to study theology, given that he received several bursaries and stipends. Indeed, he is listed in a document from 1350 as being among the teachers capable of supporting themselves without the need for financial assistance from the University.[2] Zupko has speculated that Buridan "deliberately chose to remain among the 'artists [artistae]',"[2] possibly envisioning philosophy as a secular enterprise based on what is evident to both the senses and the intellect, rather than the non-evident truths of theology revealed through scripture and doctrine.[2]

The last appearance of Buridan in historical documents came in 1359, where he was mentioned as the adjudicator in a territorial dispute between the English and Picard nations.[2] It is supposed that he died sometime after then, since one of his benefices was awarded to another person in 1362.[8]

The bishop Albert of Saxony, himself renowned as a logician, was among the most notable of his students.

An ordinance of Louis XI of France in 1473, directed against the nominalists, prohibited the reading of his works.

Apocryphal stories

Where is the very wise Heloise,

For whom was castrated, and then (made) a monk,

Pierre Esbaillart (Abelard) in Saint-Denis?

For his love he suffered this sentence.

Similarly, where is the Queen (Marguerite de Bourgogne)

Who ordered that Buridan

Were thrown in a sack into the Seine?

Oh, where are the snows of yesteryear!

Apocryphal stories abound about his reputed amorous affairs and adventures which are enough to show that he enjoyed a reputation as a glamorous and mysterious figure in Paris life.[9] None of the stories can be confirmed, and most contradict known historical information.[10]

Some rumors hold that he died when the King of France had him put in a sack and thrown into the River Seine after his affair with the Queen came to light. François Villon alludes to this in his famous poem Ballade des Dames du Temps Jadis. Others suggest that he was expelled from Paris due to his nominalist teachings and moved to Vienna to found the University of Vienna. Another story talks of him hitting Pope Clement VI with a shoe.[2][10]

Impetus theory

The concept of inertia was alien to the physics of Aristotle. Aristotle, and his peripatetic followers held that a body was maintained in motion only by the action of a continuous external force. Thus, in the Aristotelian view, a projectile moving through the air would owe its continuing motion to eddies or vibrations in the surrounding medium, a phenomenon known as antiperistasis. In the absence of a proximate force, the body would come to rest almost immediately.

The theory of impetus proposed that motion was maintained by some property of the body, imparted when it was set in motion. Buridan was the first to name this motion-maintaining property impetus but the theory itself probably did not originate with him. A less sophisticated notion of impressed forced can be found in the commentary of John Philoponus on Aristoteilan physics.[11] In this he was possibly influenced by John Philoponus who was developing the Stoic notion of hormé (impulse).[11][12] The major difference between Buridan's theory and that of his predecessor is that he rejected the view that the impetus dissipated spontaneously, instead asserting that a body would be arrested by the forces of air resistance and gravity which might be opposing its impetus. Buridan further held that the impetus of a body increased with the speed with which it was set in motion, and with its quantity of matter. This is closely related to the modern concept of momentum. Buridan saw impetus as causing the motion of the object:

- ...after leaving the arm of the thrower, the projectile would be moved by an impetus given to it by the thrower and would continue to be moved as long as the impetus remained stronger than the resistance, and would be of infinite duration were it not diminished and corrupted by a contrary force resisting it or by something inclining it to a contrary motion (Questions on Aristotle's Metaphysics XII.9: 73ra).[13]

Buridan also contended that impetus is a variable quality whose force is determined by the speed and quantity of the matter in the subject. In this way, the acceleration of a falling body could be understood in terms of its gradual accumulation of units of impetus.[11]

Legacy

Because of his developments, historians of science Pierre Duhem[14] and Anneliese Maier[15] both saw Buridan as playing an important role in the demise of Aristotelian cosmology.[16] Duhem even called Buridan the forerunner of Galileo.[17] Zupko has disagreed, pointing out that Buridan did not use his theory to transform the science of mechanics, but instead remained a committed Aristotelian in thinking that motion and rest are contrary states and that the universe is finite in extent.[11]

Selected works in English translation

- Hughes, G. E. (1983). John Buridan on Self-Reference: Chapter Eight of Buridan's Sophismata. An edition and translation with an introduction, and philosophical commentary. Cambridge/London/New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-28864-9.

- King, Peter (1986). John Buridan's Logic: The Treatise on Supposition; The Treatise on Consequences. Translation from the Latin with a Philosophical Introduction, Dordrecht: Reidel.

- Zupko, John Alexander, ed. and tr. (1990). John Buridan's Philosophy of Mind: An Edition and Translation of Book III of His Questions on Aristotle's De Anima (Third Redaction), with Commentary and Critical and Interpretative Essays. Doctoral dissertation, Cornell University.

- Klima, Gyula, tr. (2002). John Buridan: 'Summulae de Dialectica'. Yale Library of Medieval Philosophy. New Haven, Conn./London: Yale University Press.

- John Buridan (2015). Treatise on Consequences, translated, with an Introduction by Stephen Read. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Klima, G., Sobol, P. G., Hartman, P., & Zupko, J. (2023, May 31). John Buridan’s Questions on Aristotle’s de Anima - Iohannis Buridani Quaestiones in Aristotelis de Anima (Vol. 9). Springer.

References

Notes

- Kuhn, T. The Copernican Revolution, 1958, pp. 119–123.

- Zupko 2015, §1

-

Streijger, M.; Bakker, P.J.J.M.; Thijssen, J.M.M.H, eds. (2010). John Buridan: Quaestiones Super Libros De Generatione et Corruptione Aristotelis. A Critical Edition with an Introduction. Brill. p. 1. ISBN 9789004185043.

The often repeated tradition that he was born in the town of Béthune is spurious.

- Faral 1951, p. 11

- Zupko 2004, ch. 10

- Courtenay 2002

- Courtenay 2005

- Michael 1986, pp. 79–238 399–404

- Faral 1951, p. 16

- Faral 1951, p. 9-33

- Zupko 1997

- T. F. Glick, S. J. Livesay, F. Wallis, Medieval Science, Technology and Medicine:an Encyclopedia, 2005, p. 107.

- Duhem, Pierre (1906–13). Études sur Léonard de Vinci. Vol. 1–3. Paris: Hermann.

- Maier, Anneliese (1955). "Metaphysische Hintergründe der spätscholastischen Naturphilosophie". Studien zur Naturphilosophie der Spätscholastik. Rome: Storiae Letteratura.

- Grant, Edward (1971). Physical Science in the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521292948.

- Duhem 1906–13

Sources

- Clagett, Marshall (1960). The Science of Mechanics in the Middle Ages (1980. ed.). Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0299019006.

- Courtenay, William J. (2002). "Philosophy's Reward: The Ecclesiastical Income of Jean Buridan". Recherches de Théologie et Philosophie Médiévale. 68: 163–69. doi:10.2143/rtpm.68.1.859.

- Courtenay, William J. (2005). "The University of Paris at the Time of John Buridan and Nicole Oresme". Vivarium. 42 (1): 3–17. doi:10.1163/1568534042066974. S2CID 170742014.

- Faral, Edmond (1951). "Jean Buridan: Maître ès Arts de l'Université de Paris". Extrait de l'Histoire littéraire de la France. Vol. 1. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale.

- Michael, Bernd (1986). Johannes Buridan: Studien zu seinem Leben, seinen Werken und zu Rezeption seiner Theorien im Europa des späten Mittelalters [Jean Buridan: His life, his works and the reaction to his theories in the Europe of the late Middle Ages]. 2 Vols. Doctoral dissertation. University of Berlin.

- Zupko, Jack (1998). "What Is the Science of the Soul? A Case Study in the Evolution of Late Medieval Natural Philosophy". Synthese. 110 (2): 297–334. doi:10.1023/A:1004969404080. S2CID 149443888.

- Zupko, Jack (2004). John Buridan. Portrait of a Fourteenth-Century Arts Master. Notre Dame, Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 9780268032562.

- Zupko, Jack (2015). "John Buridan". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 5 February 2019.

Further reading

- Klima, Gyula (2009). John Buridan. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Landi, Marcello (2008). "Un contributo allo studio della scienza nel Medio Evo. Il trattato Il cielo e il mondo di Giovanni Buridano e un confronto con alcune posizioni di Tommaso d'Aquino" [A contribution to the study of science in the Middle Ages. The sky and the world of Jean Buridan and a comparison with some positions of St. Thomas Aquinas]. Divus Thomas. 110 (2): 151–185.

- Thijssen, J. M. M. H., and Jack Zupko (ed.) (2002). The Metaphysics and Natural Philosophy of John Buridan Leiden: Brill.

External links

- Zupko, Jack. "John Buridan". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Bibliography by Fabienne Pironet (up to 2001)

- Buridan's Logic and Metaphysics: an annotated bibliography (updates the bibliography of Fabienne Pironet to 2014)

- Buridan's Logical Works. I. An Overview of the Summulae de dialectica a detailed summary of the nine treatises of the Summulae de dialectica

- Buridan's Logical Works. II. The Treatise on Consequences and other writings a summary of the other logical writings

- Buridan: Editions, Translations and Studies on the Manuscript Tradition Complete bibliography of the logical and metaphysical works