Bush carpentry

Bush carpentry is an expression used in Australia and New Zealand that refers to improvised methods of building or repair, using available materials and an ad hoc design, usually in a pioneering or rural context.

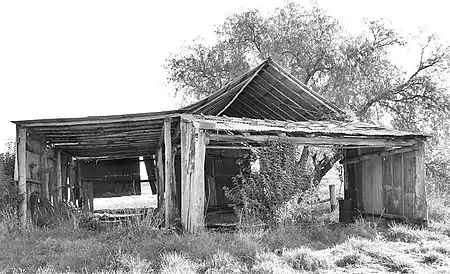

Bush carpentry in Maldon, New South Wales | |

| Places | Australia and New Zealand |

|---|---|

| Period | prehistory to the present day |

| Materials | Bush timber, wire, bark, mud, clay, concrete, stone, etc. |

| Uses | Dwellings, shops, farm outbuildings |

The tradition

The phrase 'bush carpentry' is a familiar Australian usage, but finding an exact description of its practice is rare. The Macquarie Dictionary for example, defines a bush carpenter as a rough amateur carpenter,[1] and G. A. Wilkes says he is a rough and ready carpenter.[2] The Macquarie in turn defines rough-and-ready as rough, rude or crude, but good enough for the purpose.[3] Wannan says that a bush carpenter is 'a very rough, unorthodox artisan indeed', and includes a sardonic excerpt from Henry Lawson to exemplify it.[4] In his Bushcraft series Ron Edwards describes hut and furniture building, and 'stockcamp architecture', without once using the phrase 'bush carpentry', though 'rough and ready' recurs. Tocal Agricultural College offers a course in 'Traditional bush timber construction';[5] The word 'traditional' appears six times in the course outline, but not 'bush carpentry'.[n. 1]

Cox and Lucas, writing in 1978 of Australian pioneer buildings, remarked:

"... perhaps because it has been the symbol of hardship and country toil; perhaps because it was thought too crude and rude to be treated seriously as architecture by the academics ... there have been few books and articles written on the subject ... The vernacular, often, is a fragile architectural form, evolved for expedience and resulting—especially in the case of the more primitive examples—in early decay and disappearance ... designed by an amateur, a builder with little training in design and who will be guided by a strict set of conventions developed within his own locality, perhaps paying some attention to fashion, but local only and certainly not international. Within the vernacular building, function is the dominant factor.[6]

A similar and familiar phrase is traditional bush carpentry; this implies that its principles are well-known, but informally transmitted. Like folk music, bush carpentry exists within an oral and demotic culture, and is often undocumented. The tradition of Australian inventiveness, however, has an extensive literature:

"... vigorous attitudes to innovation prevailed in the Colonies in the nineteenth century and established for Australia some significant technological leads. Lessons from these attitudes both underline the continuing importance of the 'lone inventor' and hold relevance for education, management, and technology policies today."[7][8]

Henry Lawson, "A Day on a Selection" (1896):

'The dairy is built of rotten box bark—though there is plenty of good stringy-bark within easy distance—and the structure looks as if it wants to lie down and is only prevented by three crooked props on the leaning side; more props will soon be needed in the rear for the dairy shows signs of going in that direction. The milk is set in dishes made of kerosene-tins, cut in halves, which are placed on bark shelves fitted round against the walls. The shelves are not level and the dishes are brought to a comparatively horizontal position by means of chips and bits of bark, inserted under the lower side. The milk is covered by soiled sheets of old newspapers supported on sticks laid across the dishes. This protection is necessary, because the box bark in the roof has crumbled away and left fringed holes—also because the fowls roost up there. Sometimes the paper sags, and the cream may have to be scraped off an article on dairy farming.'[9]

"The bush"

In Australian parlance, 'the bush' includes not only all remote and rural areas, but ways of living there, especially the limitations and hardships endured.[10][11][n. 2] Even though remote areas in contemporary Australia are easily reachable by air and modern communications, there remains a mythology of the tyranny of distance: tyranny over comfort, sophistication, over civilization itself. The expression bush carpentry includes two criteria of 'remoteness'. The first, that the builder is separated (by lack of formal training) from regular methods of construction. The second, separation (by physical distance) from regular resources such as milled timber, fasteners, specialized tools, and similar manufactured products. Those in both 'remote' circumstances are forced to invent and improvise. They produce a necessary structure or object via unorthodox procedures, and it will be serviceable, if inelegant in appearance.[12]

Thus, in an Australian suburb today, a self-taught handyman might devise and erect a backyard structure using purchased timber, and practising 'bush carpentry'—a gazebo, a fernery, a children's playhouse for example—while at the same time, a skilled tradesperson, in a distant run of an outback cattle station, might be forced to use heavy tree-trunks, saplings, undressed stone and rusty fencing-wire to construct a stock race.[n. 3]

These two criteria allow the use of manufactured materials—e.g. milled timber—in an irregular manner, and materials other than wood (stone and iron, for example). They exclude the fabrication of large structures like wharves and bridges, built by contracting tradesmen, which incorporate massive tree trunks, even when a manufactured item, e.g. a steel beam, is available (see illustration of Maldon Bridge repaired by government construction team).

Skills

Modern scholarship suggests Australian Aborigines were the first 'bush carpenters'. From the Aborigines, European settlers learned how to strip bark in large sheets from particular tree species, and use this for roofs and walls.[13]

Although there are few specific skills required, each must be well-mastered and neatly executed. Bush carpenters may learn from observing the methods, or the evidence of, another person's work, or entirely through their own invention. The scarcity of any reference books with any local applicability is another factor.[14]

Ron Edwards asserts that no training at all is required. The requisites are 'a calm mind, reasonable health, and a willingness to learn'. Edwards points out that the early settlers built their homes without prior knowledge and experience, and 'many of these buildings are still in existence a century later'. Edwards adds, 'Confidence in your own ability is the first requirement ... the second is access to knowledge.'[15]

In his autobiography, Sam Weller remarked of a young man who had worked for a period as a jackaroo:

"The bush is one of the best educations a young fellow can get if he's interested. That bloke knows livestock, knows how to work them, can cut a straight line with a saw, handle concrete, build a set of yards, fix a motor car—you name it. When you're a hundred miles from town, you can't afford to get a tradesman out for every little job that bobs up. So you've got to slip in and do it yourself ... One of the bosses from a cattle station told me "Sam, if a bloke comes in here in a big hat and ringer boots, he's got a job. They can turn their hands to anything. They know how to work and they don't gutsache[16] all the time."[17]

Tools

Naval carpenter, 1799

The bush carpenter historically possessed few tools, and rarely any specialized tools. Mann's Emigrant's Guide of 1849 suggests that those heading for Australia's unsettled areas take with them a plentiful supply of a wide variety of tools and fasteners, but he lists as the very minimum, 'A hand saw; Axe; Adze; Mortising chisel; Two augers, 1 and 11/4 inch; Two maul rings;[18] Set of wedges; 1 Spade; Pick-axe; Two-foot rule; Chalk line; Square; A Plumb Bob.'[19] A majority of early settlers had formerly been manual labourers, or servicemen, and brought with them a sound practical ability and aptitude for 'making do'; others observed or helped and copied their techniques.[20]

Freeland observes:

'With a saw, an axe, a hammer and a spade on his cart and possibly one of the useful little books on construction written especially for him ... he had to do the best he could with the materials that were to hand wherever he stopped. Helped a little by his book, a fair amount by advice and precedent and a great deal by ingenuity and native wit, the settlers developed a surprising number of variations on standard constructional materials and techniques.'[21]

Ron Edwards' 1987 list of suggested tools to construct 'stockcamp architecture' include only an axe, pliers, a hammer and 'perhaps an auger'. Edwards also demonstrates the technique of the Cobb & Co. hitch for tightening fencing wire that fastens structural elements(See Fig. 2 below).[22]

With the upsurge in Australia of the restoration of so-called 'Heritage items', the techniques of Australian bush carpentry may be moving closer to formal identification and categorization. Tocal College's 2002 list of tools for its 'Traditional bush timber construction' course includes the broadaxe, adze, sledge hammer[23] and wedges, morticing axe, froe and mallet, draw knife, and hand auger.[24]

Adze

Adze Augers

Augers.png.webp) Axe

Axe Broadaxe

Broadaxe Chalkline

Chalkline Drawknife

Drawknife Froe

Froe Handsaw

Handsaw Maul

Maul Pick-axe

Pick-axe Try Square

Try Square Wedge

Wedge

Design and materials

Structures or objects such as furniture created using bush carpentry techniques often have minimal or even an ad hoc design. Projects built according to properly drawn plans, for example, architectural blueprints, cannot be called examples of bush carpentry. The design of a barn or shed is likely to be intuitive and functional; the settler's slab hut derived from the vernacular English crofter's hut, a simple rectangular walled shelter with one door, and perhaps holes to allow air to enter.[25]

Historically, the materials at hand for Australian settlers usually included a plentiful supply of hardwood,[26][n. 4] in the form of fully-grown trees and saplings, bark, brush or grass, clay, mud and stone. The classic Australian bush carpentry image is the forked tree trunk used as an upright.

Nails, bolts or screws were often not available; wooden pegs, wire, or strips of greenhide might be used as fasteners. Greenhide strips might also be used as hinges for doors or shutters. Ron Edwards comments that 'Fencing wire was a very popular resource because it was always available. Bolts and long nails were expensive, and had to be ordered from town ... a shed or stockyard would be fastened together with wire and would be stronger than one that was nailed.'[27]

Less usual building materials include flattened steel kerosene containers used as wall cladding, or such containers filled with sand and used as building blocks. Sheets of hessian have also been used as walls, for coolness.[28]

The etymology of the word carpenter shows that it derives from 'a carriage maker', and later, 'one who builds frameworks';[29] thus, the term 'bush carpentry' does not necessarily imply that wood is the only material involved.

Examples of bush carpentry in situ

Fig. 1: The frame is constructed from the trunks of trees and saplings, probably obtained in the nearby Maldon Gorge.

Fig. 1: The frame is constructed from the trunks of trees and saplings, probably obtained in the nearby Maldon Gorge. Fig. 2: Fencing wire is frequently used as a fastener. The Cobb & Co. hitch is much in evidence.

Fig. 2: Fencing wire is frequently used as a fastener. The Cobb & Co. hitch is much in evidence. Fig. 3: The peaked roof has conventional ridge-pole framing, using milled timber.

Fig. 3: The peaked roof has conventional ridge-pole framing, using milled timber. Fig. 4: The only joinery in use is the half-lap; there are a few housing joints.

Fig. 4: The only joinery in use is the half-lap; there are a few housing joints.

Fig. 7: One such footing consists of a 44-gallon drum filled with concrete.

Fig. 7: One such footing consists of a 44-gallon drum filled with concrete. Fig. 8: Instead of trusses or joists to brace the walls and support the roof, strands of fencing wire are stretched between the top-plates and tensioned with turnbuckles.

Fig. 8: Instead of trusses or joists to brace the walls and support the roof, strands of fencing wire are stretched between the top-plates and tensioned with turnbuckles. Fig. 9: The northern gable-end was fashioned by nailing sheets of galvanized iron onto a sub-frame. Insecurely fastened to the main structure, it has fallen out.

Fig. 9: The northern gable-end was fashioned by nailing sheets of galvanized iron onto a sub-frame. Insecurely fastened to the main structure, it has fallen out. Fig. 10: Steel bolts secure the main structural members. One was too long, and a spacing block has been used as a washer.

Fig. 10: Steel bolts secure the main structural members. One was too long, and a spacing block has been used as a washer. Fig. 11: These split slabs may derive from an older, drop-slab structure. Nail holes are present, and the ends have been chamfered.

Fig. 11: These split slabs may derive from an older, drop-slab structure. Nail holes are present, and the ends have been chamfered. Fig. 12: A concrete footing is used instead of, or has replaced, a bottom-plate.

Fig. 12: A concrete footing is used instead of, or has replaced, a bottom-plate.

Influence on Australian architecture and art

Cox & Freeland believe that early structures created using bush carpentry had a profound influence on Australian industrial architecture:

"Because they are uncomplicated buildings, built by unlettered people in the most direct way, using the materials readily to hand, they often have a character and honesty that are rare and sometimes missing from their more erudite architectural betters. Because they are made of a material with which everyone has a deep-rooted harmony, because they are put together in ways that are easily understood and because their forms are readily comprehended, they are universal buildings whose roughness and even whose frequent dilapidation give them a powerful emotional appeal and impact. They are buildings to be felt rather than reasoned ... Cement works, mines, the railways and factories spawned a large variety of store houses and storage bins, towers and poppet heads, workshops and condensers. Framed up in peeled tree trunks or massive balks of hardwood bolted together, their skeletons of columns, beams and braces had the same forthrightness and frankness of the rural buildings ... sited out in the country where they would seldom be seen, or in ugly industrial areas, or along the waterfront where buildings were not expected to be beautiful they, like the rural buildings, were built with an eye solely to meeting their utilitarian purpose in the most direct and purposeful way. Because of this, they frequently succeeded in being outstandingly beautiful. Through the industrial buildings, the functional tradition of the countryside unknowingly and unconsciously was passed into the twentieth century.[30]

The cartoons of Eric Jolliffe, especially those based on his character Saltbush Bill include many examples of bush carpentry; the farm where much of Saltbush Bill is set has houses, furniture and other rural structures—barns, stockyards, gallows—all built using bush carpentry means and materials. Joliffe set himself the task of preserving much of Australia's rural heritage by producing sketches and paintings of such structures.[31][32]

In Australian literature and music

There is often a sardonic or comical note in Australian fiction when bush carpentry is mentioned or described; possibly because there is no comedy or satire residing in competency.

Rolf Boldrewood's Robbery Under Arms(1881) is an exception:

'... It was a snug hut enough, for father was a good bush carpenter, and didn't turn his back to any one for splitting and fencing, hut-building and shingle-splitting; he had had a year or two at sawing, too ... he took great pride ... and said it was the best-built hut within fifty miles. He split every slab, cut every post and wallplate and rafter himself, with a man to help him at odd times; and after the frame was up, and the bark on the roof, he camped underneath and finished every bit of it – chimney, flooring, doors, windows, and partitions – by himself.'[33]

Henry Lawson, "The Darling River" (1900):

"The boat we were on was built and repaired above deck after the different ideas of many bush carpenters, of whom the last seemed by his work to have regarded the original plan with a contempt only equalled by his disgust at the work of the last carpenter but one. The wheel was boxed in, mostly with round sapling-sticks fastened to the frame with bunches of nails and spikes of all shapes and sizes, most of them bent. The general result was decidedly picturesque in its irregularity, but dangerous to the mental welfare of any passenger who was foolish enough to try to comprehend the design; for it seemed as though every carpenter had taken the opportunity to work in a little abstract idea of his own.[34]

In Steele Rudd's, Back at Our Selection, (1906) the sequence of stories beginning with "Dave's New House" and ending with "Dad Forgets the Past" have a socio-historical sub-text emphasizing the progress of rural Australia from pioneering to prosperity. In the first story, Dad Rudd, though now a wealthy farmer, builds Dave and his new wife Lily a house, using materials salvaged from a neighbour's derelict slab hut. Dad still thinks like a pioneer: he constructs the house himself, using only the materials available, and spending little or no money. However, Lily's mother is outraged that her daughter is expected to live in 'a pile of dirty old slabs and shingles ... a hole!' Dad Rudd is shamed into hiring proper building contractors and erecting a fine cottage, at a cost of 'three hundred pounds'; indeed, in freeing himself from the penuriousness he knew as a penniless settler, Dad over-furnishes Dave's house such that even Mother 'shook her head disapprovingly'.[35]

E. O. Schlunke's The Enthusiastic Prisoner (1955) shows two bush carpenters at work. One is a lazy Australian farmer who is assigned an Italian prisoner of war as a laborer. The Italian is far more energetic, and tackles dozens of neglected farming tasks, becoming in effect the manager. In one episode, they re-roof a shed using bush carpentry:

'When they climbed the roof Pietro discovered that half the sheets were loose. Henry gave him the nails and directed him to nail down the flapping sheet. But Pietro was hunting round for causes. He discovered that the rafters were rotting and demonstrated it by giving one a hard hit with the hammer. It split from end to end and a couple of sheets immediately blew off the roof.

They spent the afternoon cutting trees in the scrub and trimming them for rafters, though nothing had been farther from Henry's intention and inclination. He cut down a few little trees while Pietro cut a lot of big ones. Pietro always took the heavier end when they loaded the rails, but even so, Henry became exhausted. Round about four o'clock he decided to go home.

"Sufficient", he said.

Pietro consulted a diagram he had made.

"No sufficient", he said. "Ancora four."

... They finished re-roofing the shed by the week-end. Pietro wanted to know if they would cut some fence-posts next week to repair the fences. Henry thought of how he would suffer if he had to work on the other end of a cross-cut saw with a tireless bear like Pietro.

"No", he said, "some other work."

But he didn't like the way Pietro looked at him, so he decided to hide the cross-cut saw.'[36]

The folk song Stringbark and Greenhide describes successful bush carpentry using both these materials:

If you want to build a hut, to keep out wind and weather,

Stringy bark will make it snug, and keep it well together;

Greenhide, if it's used by you, will make it all the stronger,

For if you tie it with greenhide, it's sure to last the longer.

The folk song Old Bark Hut is of another opinion:

In the summertime when the weather's warm this hut is nice and cool

And you'll find the gentle breezes blowing in through every hole

You can leave the old door open or you can leave it shut

There's no fear of suffocation in the old bark hutIn an old bark hut in an old bark hut

There's no fear of suffocation in the old bark hut.[37]

Shacks, cabins and weekenders

From the 1920s to the 1970s, the average Australian family aimed to own a 'weekender', in addition to their suburban dwelling. (In New Zealand, a weekender is known as a bach). On a block of land close to a beach, near a coastal village, or other place of recreation like a river, lake or mountain, a family might erect a 'shack', or cabin, usually with their own hands, often using materials brought from their city residence, or obtained nearby. Shacks and cabins used as weekenders were sometimes built illegally, in remote or inaccessible areas, for example, within National Parks.[38] Weekenders were not always constructed according to the local council's building code; they were often excellent examples of bush carpentry.

Government organizations usually ignored the presence and the irregular construction of such weekenders, provided the users behaved responsibly. Municipal councils did not charge these shack-builders rates, and did not provide services like water supply, power, sewerage or garbage disposal. By the 1980s, however, as Australia's population increased, many former coastal villages had become towns, or the suburbs of nearby towns. Many Australians had retired to live cheaply in their weekender,[n. 5] placing increasing pressure on local infrastructure and community services.[39] Increasing pressure was then placed on the owners and occupiers of weekenders to destroy or replace their shack with a properly constructed dwelling.[40]

The founding of the National Parks and Wildlife Service in 1967 introduced a policy of cabin removal. Owners have subsequently sought to have their cabins declared heritage structures, 'uncommon and endangered examples of vernacular weekender architecture construction' and of 'the limitations imposed by the natural environment and isolated location' i.e. examples of bush carpentry.[41][42]

Notes and references

- Notes

- Bush carpentry may lack a literature due to its perceived inferiority as a practice, e.g. the catalogue of the Australian National Library has no Subject Heading for Bush Carpentry.

- Similar slang expressions in English include 'the boondocks'; 'the tall rhubarbs'; 'the sticks'; all implying remoteness and lack of sophistication.

- The increasing availability today of prefabricated structures in kit form make both examples less and less likely, but the expression remains in use.

- The toughness and intractability of Australian hardwoods discouraged attempts at detailed joinery. Fancy, carved bargeboards were never a feature of settlers' dwellings, and whittling never became an Australian pioneer's pastime.

- That is, made a seachange

- References

- The Macquarie Dictionary 1981 edition, p. 270

- Wilkes, The Australian Language

- Mac. Dict. 1981, p. 1504

- Wannan, Australian Folklore

- One day Tocal College course

- Cox, 1978. Introduction.

- Moyal. "Invention and Innovation in Australia ..."

- Australian inventions Archived 16 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- Lawson, While the Billy Boils

- Baker, Sidney, 1978. The Australian Language. Chapter IV. Currawong. ISBN 0-908001-06-1

- Wilkes, G. A. 1987. A Dictionary of Australian Colloquialisms. Fontana. ISBN 0-00-635719-9

- Dingle, T. "Necessity the Mother of Invention" in Troy, pp. 61–63

- Archer, John. The Great Australian Dream. First and fourth chapters.

- Lewis 5.03.3; Freeland p. 102.

- Bushcraft 3, p. 8

- complain; find fault, whinge

- Weller, Sam. Old Bastards I Have Met

- Iron collars that prevent damage to a maul's handle

- Mann, cited in Cox, Rude Timber Buildings p. 42

- Dingle, T. "Necessity the Mother of Invention" in Troy, pp. 61–63

- Freeland, pp. 102–3.

- Edwards, Bushcrafts 2 p. 30

- Traditional timber-splitting used a maul; a sledge-hammer is a more general purpose tool

- Tocal Bush Timber Construction course

- Slab hut and floor plan, 1840 N.L.A.

- Edwards notes that shortage of suitable softwood, which can be worked with simple tools, made the traditional log cabin a less familiar sight on the Australian scene. Edwards, Bushcrafts 3.

- Bushcrafts 2, p. 38.

- Edwards, Bushcrafts 3.

- Shorter Oxford Dictionary Third ed. 1980

- Cox Rude Timber Buildings. Foreword; p. 53

- Eric Jolliffe bio.

- "Cartoon examples". Archived from the original on 13 January 2010. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- "Robbery Under Arms, Chapter 1". Archived from the original on 13 October 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2010.

- Over the Sliprails at Google Books

- Rudd, Back at Our Selection.

- Schlunke, E. O. 1955. The man in the silo : and other stories. Angus and Robertson.

- There are many variations in the words of these songs. See Edwards, Ron. 1991. Great Australian Folk Songs Ure Smith Press. ISBN 0-7254-0861-8

- Holiday shacks in Tasmania built by 'squatters'

- Retirees in coastal towns Archived 22 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- Illegal Building Works Archived 4 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- NSW Parliament – Royal National Park Cabins

- Royal National Park, Coastal Cabins Areas Management Plan. Retrieved 7 July 2010

Bibliography and further reading

- Archer, Cameron, et al. 2002. Conservation of Timber Buildings and Fences at Tocal. C. B. Alexander College, Tocal. ISBN 0-7313-0557-4

- Archer, John. 1996. The Great Australian Dream: the history of the Australian house. HarperCollins, Pymble. ISBN 0-207-19003-8

- Baker, Sidney J. 1966. The Australian Language: an examination of the English language and English speech as used in Australia, from convict days to the present ... Currawong, Sydney.

- Berry, D.W. & Gilbert, S.H. 1981. Pioneer Building Techniques in South Australia. Adelaide, Gilbert-Partners, ISBN 0-9594160-0-5

- Cox, P., & Freeland, J. 1969. Rude timber buildings in Australia. Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-34035-8

- Cox, P., & Lucas, C. 1978. Australian Colonial Architecture. Lansdowne. ISBN 1-86302-343-7

- Baglin, Douglass, Mullins, Barbara. 1973. Rough as Guts Eclipse, Dee Why. ISBN 978-0-85895-088-7

- Edwards, Ron. 1988. Bushcraft 1: Australian Traditional Bush Crafts. Rams Skull Press, Kuranda. ISBN 0-909901-74-0

- Edwards, Ron. 1988. Bushcraft 2: Skills of the Australian Bushman. Rams Skull Press, Kuranda. ISBN 0-909901-75-9

- Edwards, Ron. 1987. Bushcraft 3: More Australian Traditional Bush Crafts. Rams Skull Press, Kuranda. ISBN 0-909901-67-8

- Fearn-Wannan, W. 1970. Australian Folklore: a Dictionary of Lore, Legends and Popular Allusions Lansdowne, Melbourne. ISBN 0-7018-0088-7. p. 109.

- Freeland, J. M. 1974. Architecture in Australia. Pelican, 1974.

- Herman, Morton. 1954. The Early Australian Architects and Their Work. Angus and Robertson, Sydney.

- Mann, Robert James. 1849. Mann's emigrant's guide to Australia : including the colonies of New South Wales, Port Philip, South Australia, Western Australia, and Moreton Bay London : William Strange.

- Moyal, A. 1987. "Invention and Innovation in Australia: the historian's lens". Prometheus, Volume 5, Issue 1, pp 92–110

- Rudd, Steele. 1973. Our New Selection; Sandy's Selection; Back at Our Selection. Lloyd O'Neil, Sydney. See ISBN 0-85558-416-5

- Troy, P. (ed.) 2000. A History of European Housing in Australia. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-77733-X

- Walker, M. 1978. Pioneer Crafts of Early Australia. Macmillan, Melbourne. ISBN 0-333-25191-1

- Weller, Sam. 1979. Old Bastards I Have Met. Sampal Investments, Charters Towers.

- Welsh, Peter. Woodworking Tools 1600–1900 At Project Gutenberg.

- Wilkinson, G. B. 1849. The working man's handbook to South Australia, with advice to the farmer, and detailed information for the several class of labourers and artisans. London : Murray.

External links

Newspaper Articles

Building and Bushwork for Selectors, Squatters, and Others a series of articles by Frederick Harrison, appearing in The Australian Town and Country Journal during June–August 1881.

THE object of the papers prepared for publication under the above heading is to provide, in a concise form, information constantly required by employers and employed especially in the country districts of Australia. The reason for adapting the subjects specially to bush requirements is obvious. Take up any English work, and the materials specified, such as stone, lime, timber, &c, are those indigenous to or easily obtained in that country. But that does not answer for the bush, where the materials available on the spot must be utilized.

- Part I : Introduction

- Part II : Materials – Timber

- Part III : Felling Timber

- Part IV : Sawing

- Part V : Brickmaking

- Part VI : Floors

Historical images: Australia

- Bush carpenter at work N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection.

- Bush carpentry: pig sty N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection.

- Bush carpentry: bark hut frame N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection.

- Bush carpentry: meat house N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection.

- Bush carpentry: slab hut N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection.

- Bush carpentry: bark hut N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection

- Bush carpentry: slab homestead N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection

- Bush carpentry: houses and stockyards N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection

- Bush carpentry: outdoor kitchen N.L.A. Australian Inland Mission Collection

Other links

- Bodging, furniture carpentry done with green, unseasoned wood

- "Bowen River Hotel (entry 600042)". Queensland Heritage Register. Queensland Heritage Council. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- Victorian High Country Huts Association

- Urban Bush Carpenters

- Colonial Slab Hut construction

- Australian architecture – being good or being different 'Australian eucalypts are wonky. Any builder using them just had to accept that there would be gaps in their walls ...'

- Gay Hawkes Bush Carpentry sculpture 'From timbers which are cast off from another life she fashions objects which cleverly identify Australia and Australians.'