Buteo

Buteo is a genus of medium to fairly large, wide-ranging raptors with a robust body and broad wings. In the Old World, members of this genus are called "buzzards", but "hawk" is used in the New World (Etymology: Buteo is the Latin name of the common buzzard[1]). As both terms are ambiguous, buteo is sometimes used instead, for example, by the Peregrine Fund.[2]

| Buteo Temporal range: Oligocene – present | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common buzzard (Buteo buteo) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Accipitriformes |

| Family: | Accipitridae |

| Subfamily: | Buteoninae |

| Genus: | Buteo Lacépède, 1799 |

| Type species | |

| Falco buteo Linneaus, 1758 | |

| Species | |

|

About 30, see text | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Asturina | |

Characteristics

Buteos are fairly large birds. Total length can vary from 30 to 75 cm (12 to 30 in) and wingspan can range from 67 to 170 cm (26 to 67 in). The lightest known species is the roadside hawk,[lower-alpha 1] at an average of 269 g (9.5 oz) although the lesser known white-rumped and Ridgway's hawks are similarly small in average wingspan around 75 cm (30 in), and average length around 35 cm (14 in) in standard measurements. The largest species in length and wingspan is the upland buzzard, which averages around 65 cm (26 in) in length and 152 cm (60 in) in wingspan. The upland is rivaled in weight and outsized in foot measurements and bill size by the ferruginous hawk. In both of these largest buteos, adults typically weigh over 1,200 g (2.6 lb), and in mature females, can exceed a mass of 2,000 g (4.4 lb).[5][6][7][8] All buteos may be noted for their broad wings and sturdy builds. They frequently soar on thermals at midday over openings and are most frequently seen while doing this. The flight style varies based on the body type and wing shape and surface size. Some long-winged species, such as rough-legged buzzards and Swainson's hawks, have a floppy, buoyant flight style, while others, such as red-tailed hawks and rufous-tailed hawks, tend to be relatively shorter-winged, soaring more slowly and flying with more labored, deeper flaps.[5] Most small and some medium-sized species, from the roadside hawk to the red-shouldered hawk, often fly with an alternation of soaring and flapping, thus may be reminiscent of an Accipiter hawk in flight, but are still relatively larger-winged, shorter-tailed, and soar more extensively in open areas than Accipiter species do.[5][9] Buteos inhabit a wide range of habitats across the world, but tend to prefer some access to both clearings, which provide ideal hunting grounds, and trees, which can provide nesting locations and security.[6][7]

Diet

All Buteo species are to some extent opportunistic when it comes to hunting, and prey on almost any type of small animal as it becomes available to them. However, most have a strong preference for small mammals, mostly rodents. Rodents of almost every family in the world are somewhere preyed upon by Buteo species.[5][6][7] Since many rodents are primarily nocturnal, most buteos mainly hunt rodents that may be partially active during the day, which can include squirrels and chipmunks, voles, and gerbils. More nocturnal varieties are hunted opportunistically and may be caught in the first or last few hours of light.[5][7] Other smallish mammals, such as shrews, moles, pikas, bats, and weasels, tend to be minor secondary prey, although can locally be significant for individual species.[5][7] Larger mammals, such as rabbits, hares, and marmots, including even adult specimens weighing as much as 2 to 3 kg (4.4 to 6.6 lb), may be hunted by the heaviest and strongest species, such as ferruginous,[7][10][11] red-tailed[12] and white-tailed hawks.[13] Birds are taken occasionally, as well. Small to mid-sized birds, i.e. passerines, woodpeckers, waterfowl, pigeons, and gamebirds, are most often taken. However, since the adults of most smaller birds can successfully outmaneuver and evade buteos in flight, much avian prey is taken in the nestling or fledgling stages or adult birds if they are previously injured.[5][7] An exception is the short-tailed hawk, which is a relatively small and agile species and is locally a small bird-hunting specialist.[14] The Hawaiian hawk, which evolved on an isolated group of islands with no terrestrial mammals, was also initially a bird specialist, although today it preys mainly on introduced rodents. Other prey may include snakes, lizards, frogs, salamanders, fish, and even various invertebrates, especially beetles. In several Buteo species found in more tropical regions, such as the roadside hawk or grey-lined hawk, reptiles and amphibians may come to locally dominate the diet.[5] Swainson's hawk, despite its somewhat large size, is something of exceptional insect-feeding specialist and may rely almost fully on crickets and dragonflies when wintering in southern South America.[15][16] Carrion is eaten occasionally by most species, but is almost always secondary to live prey.[5] The importance of carrion in the Old World "buzzard" species is relatively higher since these often seem slower and less active predators than their equivalents in the Americas.[17][18][19] Most Buteo species seem to prefer to ambush prey by pouncing down to the ground directly from a perch. In a secondary approach, many spot prey from a great distance while soaring and circle down to the ground to snatch it.[5]

Reproduction

Buteos are typical accipitrids in most of their breeding behaviors. They all build their own nests, which are often constructed out of sticks and other materials they can carry. Nests are generally located in trees, which are generally selected based on large sizes and inaccessibility to climbing predators rather than by species. Most Buteos breed in stable pairs, which may mate for life or at least for several years even in migratory species in which pairs part ways during winter. Generally from 2 to 4 eggs are laid by the female and are mostly incubated by her, while the male mate provides food. Once the eggs hatch, the survival of the young is dependent upon how abundant appropriate food is and the security of the nesting location from potential nest predators and other (often human-induced) disturbances. As in many raptors, the nestlings hatch at intervals of a day or two and the older, strong siblings tend to have the best chances of survival, with the younger siblings often starving or being handled aggressively (and even killed) by their older siblings. The male generally does most of the hunting and the female broods, but the male may also do some brooding while the female hunts as well. Once the fledgling stage is reached, the female takes over much of the hunting. After a stage averaging a couple of weeks, the fledglings take the adults increasing indifference to feeding them or occasional hostile behavior towards them as a cue to disperse on their own. Generally, young Buteos tend to disperse several miles away from their nesting grounds and wander for one to two years until they can court a mate and establish their own breeding range.[5][6][7]

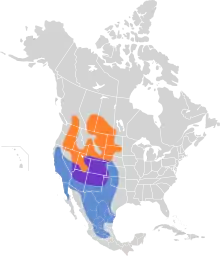

Distribution

The Buteo hawks include many of the most widely distributed, most common, and best-known raptors in the world. Examples include the red-tailed hawk of North America and the common buzzard of Eurasia. Most Northern Hemisphere species are at least partially migratory. In North America, species such as broad-winged hawks and Swainson's hawks are known for their huge numbers (often called "kettles") while passing over major migratory flyways in the fall. Up to tens of thousands of these Buteos can be seen each day during the peak of their migration. Any of the prior mentioned common Buteo species may have total populations that exceed a million individuals.[5] On the other hand, the Socotra buzzard and Galapagos hawks are considered vulnerable to extinction per the IUCN. The Ridgway's hawk is even more direly threatened and is considered Critically Endangered. These insular forms are threatened primarily by habitat destruction, prey reductions and poisoning.[5][6] The latter reason is considered the main cause of a noted decline in the population of the more abundant Swainson's hawk, due to insecticides being used in southern South America, which the hawks ingest through crickets and then die from poisoning.[20]

Taxonomy and systematics

The genus Buteo was erected by the French naturalist Bernard Germain de Lacépède in 1799 by tautonymy with the specific name of the common buzzard Falco buteo which had been introduced by Carl Linnaeus in 1758.[21][22]

Extant species in taxonomic order

Fossil record

A number of fossil species have been discovered, mainly in North America. Some are placed here primarily based on considerations of biogeography, Buteo being somewhat hard to distinguish from Geranoaetus based on osteology alone:[52]

- †Buteo dondasi (Late Pliocene of Buenos Aires, Argentina)

- †Buteo fluviaticus (Brule Middle? Oligocene of Wealt County, US) – possibly same as B. grangeri

- †Buteo grangeri (Brule Middle? Oligocene of Washabaugh County, South Dakota, US)

- †Buteo antecursor (Brule Late? Oligocene)

- †?Buteo sp. (Brule Late Oligocene of Washington County, US)[53]

- †Buteo ales (Agate Fossil Beds Early Miocene of Sioux County, US) – formerly in Geranospiza or Geranoaetus

- †Buteo typhoius (Olcott Early ?- snake Creek Late Miocene of Sioux County, US)

- †Buteo pusillus (Middle Miocene of Grive-Saint-Alban, France)

- †Buteo sp. (Middle Miocene of Grive-Saint-Alban, France – Early Pleistocene of Bacton, England)[54]

- †Buteo contortus (snake Creek Late Miocene of Sioux County, US) – formerly in Geranoaetus

- †Buteo spassovi (Late Miocene of Chadžidimovo, Bulgaria)[55]

- †Buteo conterminus (snake Creek Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Sioux County, US) – formerly in Geranoaetus

- †Buteo sp. (Late Miocene/Early Pliocene of Lee Creek Mine, North Carolina, US)

- †Buteo sanya (Late Pleistocene of Luobidang Cave, Hainan, China)

- †Buteo sanfelipensis (Late Pleistocene, Cuba)

An unidentifiable accipitrid that occurred on Ibiza in the Late Pliocene/Early Pleistocene may also have been a Buteo.[57] If this is so, the bird can be expected to aid in untangling the complicated evolutionary history of the common buzzard group.

The prehistoric species "Aquila" danana, Buteogallus fragilis (Fragile eagle), and Spizaetus grinnelli were at one time also placed in Buteo.[52]

Notes

- The roadside hawk is now considered to be in a separate monotypic genus Rupornis (Kaup 1844)[3][4]

- A binomial authority in parentheses indicates that the species was originally described in a genus other than Aviceda .

References

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 81. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- "Buteos at the Peregrine Fund". peregrinefund.org. Archived from the original on 2007-02-12.

- Kaup, Johann Jakob (1844). Classification der Säugethiere und Vögel (in German). Darmstadt: Carl Wilhelm Leske. p. 120. Retrieved 28 December 2022 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (August 2022). "Hoatzin, New World vultures, Secretarybird, raptors". IOC World Bird List Version 12.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 28 December 2022.

- Ferguson-Lees, J.; Christie, D. (2001). Raptors of the World. London: Christopher Helm. ISBN 0-7136-8026-1.

- del Hoyo, J.; Elliot, A. & Sargatal, J. (editors). (1994). Handbook of the Birds of the World Volume 2: New World Vultures to Guineafowl. Lynx Edicions. ISBN 84-87334-15-6

- Eagles, Hawks and Falcons of the World by Leslie Brown & Dean Amadon. The Wellfleet Press (1986), ISBN 978-1555214722.

- CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses by John B. Dunning Jr. (Editor). CRC Press (1992), ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- Crossley, R., Liguori, J. & Sullivan, B. The Crossley ID Guide: Raptors. Princeton University Press (2013), ISBN 978-0691157405.

- Smith, D. G. and J. R. Murphy. 1978. Biology of the Ferruginous Hawk in central Utah. Sociobiology 3:79-98.

- Thurow, T. L., C. M. White, R. P. Howard, and J. F. Sullivan. 1980. Raptor ecology of Raft River valley, Idaho. EG&G Idaho, Inc. Idaho Falls.

- Smith, D. G. and J. R. Murphy. 1973. Breeding ecology of raptors in the East Great Basin Desert of Utah. Brigham Young Univ. Sci. Bull., Biol. Ser. Vol. 18:1-76.

- Kopeny, M. T. 1988a. White-tailed Hawk. Pages 97–104 in Southwest raptor management symposium and workshop. (Glinski, R. L. and et al., Eds.) Natl. Wildl. Fed. Washington, D.C.

- Ogden, J. C. 1974. The Short-tailed Hawk in Florida. I. Migration, habitat, hunting techniques, and food habits. Auk 91:95-110.

- Snyder, N. F. R. and J. W. Wiley. 1976. Sexual size dimorphism in hawks and owls of North America. Ornithol. Monogr. no. 20.

- Jaramillo, A. P. 1993. Wintering Swainson's Hawks in Argentina: food and age segregation. Condor 95:475-479.

- Tubbs, C.R. 1974. The buzzard. David & Charles, Newton Abbot.

- Wu, Y.-Q., M. Ma, F. Xu, D. Ragyov, J. Shergalin, N.F. Lie, and A. Dixon. 2008. Breeding biology and diet of the Long-legged Buzzard (Buteo rufius) in the eastern Junggar Basin of northwestern China. Journal of Raptor Research 42:273-280.

- Allan, D.G. 2005. Jackal Buzzard Buteo rufofuscus. P.A.R. Hockey, W.R.J. Dean, and P.G. Ryan (eds.). Pp. 526–527 in Roberts Birds of Southern Africa. VIIth ed. Trustees of the John Voelcker Bird Book Fund, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Weidensaul, S. Living on the Wind: Across the Hemisphere With Migratory Birds. North Point Press (2000), ISBN 978-0865475915.

- Lacépède, Bernard Germain de (1799). "Tableau des sous-classes, divisions, sous-division, ordres et genres des oiseux". Discours d'ouverture et de clôture du cours d'histoire naturelle (in French). Paris: Plassan. p. 4. Page numbering starts at one for each of the three sections.

- Mayr, Ernst; Cottrell, G. William, eds. (1979). Check-list of Birds of the World. Volume 1 (2nd ed.). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 361.

- "ITIS Report: Butastur". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- BirdLife International (2013). "Buteo buteo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo japonicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo refectus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo socotraensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International. (2016). Buteo jamaicensis. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22695933A93534834.en.

- BirdLife International (2013). "Buteo rufinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2013). "Buteo lagopus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo regalis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo lineatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo platypterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo swainsoni". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2013). "Buteo ridgwayi". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo brachyurus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo albigula". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo galapagoensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo nitidus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22727766A94961368. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22727766A94961368.en.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo plagiatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2017.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo albonotatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo solitarius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2015). "Buteo ventralis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- BirdLife International (2016). "Buteo oreophilus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22728020A94968444. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22728020A94968444.en.

- BirdLife International (2017). "Buteo trizonatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017: e.T22735392A118530114. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2017-3.RLTS.T22735392A118530114.en.

- "Buteo brachypterus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 25 October 2016.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo hemilasius". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- "Buteo auguralis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Archived from the original on 28 October 2016. Retrieved 27 October 2016.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo rufofuscus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- BirdLife International (2012). "Buteo augur". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- Ferguson-Lees, J., & Christie, D. A. (2001). Raptors of the world. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Wetmore (1933)

- A complete left ulna similar to Buteo but of distinctly small size: Cracraft (1969)

- Probably several species; similar to Common Buzzard in appearance and size: Ballmann (1969), Mlíkovský (2002)

- Boev, Z., D. Kovachev. 1998. Buteo spassovi sp. n. - a Late Miocene Buzzard (Accipitridae, Aves) from SW Bulgaria. - Geologica Balcanica, 29 (1-2): 125–129.

- Brodkorb (1962), Mlíkovský (2002)

- Alcover (1989)

Further reading

- "Raptors of the World" by Ferguson-Lees, Christie, Franklin, Mead & Burton. Houghton Mifflin (2001), ISBN 0-618-12762-3.

- Alcover, Josep Antoni (1989): Les Aus fòssils de la Cova de Ca Na Reia. Endins 14-15: 95-100. [In Catalan with English abstract]

- Ballmann, Peter (1969): Les Oiseaux miocènes de la Grive-Saint-Alban (Isère) [The Miocene birds of Grive-Saint-Alban (Isère)]. Geobios 2: 157–204. [French with English abstract] doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(69)80005-7 (HTML abstract)

- Brodkorb, Pierce (1964): Catalogue of Fossil Birds: Part 2 (Anseriformes through Galliformes). Bulletin of the Florida State Museum 8(3): 195–335. PDF or JPEG fulltext

- Cracraft, Joel (1969): Notes on fossil hawks (Accipitridae). Auk 86(2): 353–354. PDF fulltext

- Mlíkovský, Jirí (2002): Cenozoic Birds of the World, Part 1: Europe. Ninox Press, Prague. ISBN 80-901105-3-8 PDF fulltext

- Wetmore, Alexander (1933): Status of the Genus Geranoaëtus. Auk 50(2): 212. DjVu fulltext PDF fulltext

.jpg.webp)

_-_Blue_Cypress_Lake%252C_Florida.jpg.webp)

_RWD.jpg.webp)

_(8082820954).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_blue_haven_road%252C_patagonia%252C_santa_cruz_co%252C_az_-02_(16906279787).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)