Byron Randall

Byron Randall (October 23, 1918 – August 11, 1999) was an American West Coast artist, well known for his expressionist paintings and printmaking. A contemporary of artists Pablo O'Higgins, Anton Refregier, Robert P. McChesney, Emmy Lou Packard (his second wife), and Pele de Lappe (his final companion), Randall shared their left wing politics while exploring different techniques and styles, including a vivid use of color and line.

Byron Randall | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Byron Theodore Randall October 23, 1918 Tacoma, Washington, U.S. |

| Died | August 11, 1999 (aged 80)[1] |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting and Printmaking |

| Movement | Social Realism, Expressionism |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Nelson (1940–1956), Emmy Lou Packard (1959–1972), Eve Wieland (1982–1986) |

| Partner | Pele de Lappe (1990–1999) |

Biography

Born in Tacoma, Washington, Byron Theodore Randall was raised in Salem, Oregon, where he worked as a waiter, harvest hand, boxer, and cook for the Marion County jail to finance his art career. In 1939 Randall trained under Louis Bunce and Charles Val Clear at the Federal Art Project's Salem Art Center; he subsequently taught there.[2] When he was 20 years old, a solo show at the Whyte Gallery in Washington D.C. brought his work to the attention of Newsweek and launched his professional career.[3] That exhibit was followed by others, over the years, in places that include Baltimore, Salem Oregon, Chicago, New York City, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, Seattle, Indianapolis, Toronto, Montreal, Moscow, Edinburgh, Leeds, and Inverness (Scotland).

Randall had three wives. His first wife was Helen Nelson, a Canadian sculptor, whom he met at the Salem Art Center while attending her classes, in 1939. Nelson was brought over from New York to be the first instructor in sculpture for the blind at the Center.[4] She sharpened his commitment to social and trade union activism, and her belief in his talent provided vital support for the fledgling artist. In 1940 they married and moved to Mexico for six months, where they had a child, Gale, and where Randall continued to develop as a painter, inspired by the vibrant landscape and people.[5] During the Second World War years, while Randall served in the Merchant Marines, he continued to paint whenever possible. His experiences in the South Pacific influenced his preference for natural forms and bright colors.

After the war, Randall traveled to Eastern Europe, as arts correspondent for a Canadian news agency, where he witnessed and painted the post-war devastation of Yugoslavia and Poland.[6] Randall and Helen settled in the North Beach area of San Francisco where they had a second child, Jonathan, in 1948. Five years later they left the United States for Canada, to escape McCarthyite anti-Communism; they had both been in the US Communist Party. In 1956, Helen died in a traffic accident.[7]

Randall and his children returned to San Francisco where he subsequently married the print-maker and muralist Emmy Lou Packard. Between 1959 and 1968 Randall and Packard ran a Guest House and Art Gallery in Mendocino, California. They were political and environmental activists, involved in the campaign to protect the area from commercial despoliation and in the creation of the Peace and Freedom Party. They attended the World Congress for Peace, National Independence and General Disarmament, Helsinki, July 10–15, as U.S. Delegates.[8]

After the end of their marriage,[9] Randall established a guesthouse/art gallery in Tomales, California. He converted a dilapidated chicken coop to become his home and studio, in 1971. This conversion brought him national attention.[10] So did his huge collection of potato mashers.[11] In 1982, he married Eve Wieland, an Austrian wartime emigre. She was his wife until her death from cancer four years later.

For the last nine years of his life, Randall's partner was Pele deLappe, an artist and friend of some 50 years standing.[12] Randall died in San Francisco on August 11, 1999, at the age of 80 after a battle with emphysema.[13]

Career

Randall was an expressionist whose art was strongly responsive to physical environment. Of his paintings he wrote: "the look of them might have been different if I'd grown up anywhere but in Oregon. Brilliant sunlight nursing the green valleys after a long rainy winter . . . there's a powerful bit of environment that would show in a man's work all his life. I've seen that creative communication has a vitality all its own. It's not a refuge from life, but an intensification. It's the practice of humanity. In painting I think the approach that best affirms life is expressionism, and that's why I became and am now an expressionist."[14]

A predominantly figurative artist, Randall experimented with abstraction in the 1940s, and again in the 1980s and 1990s. Throughout his career he produced still lifes, portraits, nudes and landscapes, in oil, watercolor, gouache, pastel, and print. He also developed plaster sculpture, and three-dimensional collages on the theme of the sea (a recurrent interest). Randall's concern for social justice ran across his career. It was most explicit in art from the 30s through to the 50s, such as his 1947 'Diabolical Machines' print (held in numerous museums), his Spanish Civil War painting (at Hallie Ford Museum), and his prints of dispossessed Jews from the ghettos of Eastern Europe (at LA Museum of the Holocaust), created from firsthand observation. In the 1960s, Randall satirically explored what was for him the grotesque pageantry of US militarism, using a visual vocabulary of ghastly females, skulls and skeletons that drew upon the folk traditions of Mexican graphic art. As a contrast, he invoked the US's own iconic imagery of liberty and democracy, embodied in Abraham Lincoln, to whom Randall dedicated a series of oil paintings spanning two decades.

Randall saw the human condition as a dynamic struggle for justice or at times simply the struggle for survival, captured in his lifelong scenes of boxers and wrestlers. Not only human but also planetary survival struggles caught his visual imagination. The threat of nuclear apocalypse prompted a series of huge oils, titled 'Doomsday', in the late 1950s and 1960s. The Crocker Museum, the Jundt Museum, and Smith College Art Museum hold oils from this series. Randall's late works of the 1980s and 1990s deploy a personal mythology of skulls, Mickey Mouse, Lucifer, and nude articulated dolls to ponder the chaotic horrors, and surrealism, of consumer culture. 'Flotsam and Jetsam', his print series of small lino and wood cuts and related large oils, is the summation of this political exploration.

Randall's art revels in the joyful, sensuous and whimsical aspects of everyday life. It celebrates both male and female nudity, and the hedonistic satisfactions of leisure: surfing, drinking, dancing, lounging, making music. From early on, Randall's love of tools featured in his work, animating his popular 'Philo' oil series of West Coast barns, plows and shovels. Tools and vessels often make their way into his still lifes, as do nudes, who are often slyly incorporated into landscapes and still lifes. Randall saw in manual labor the affirmative potential of a non-industrialized life. This led him to unsentimental, international portraits, in paint and print, of working people, as hewers of coal and wood, house painters, diggers, laundry women, cooks, carpenters, farmhands, stevedores, sellers of bread, balloons, and chickens. The landscapes of rural Oregon, California, Hawaii, Canada, Mexico and Scotland stimulated Randall, as a watercolorist, to the use of intensely vivid colors and energetic brushstroke. Urban life also claimed his attention, from his early, gloomy cityscapes of New York, and on to 1950s scenes of Montreal and San Francisco.

Organizing, public art, and peace activity

Randall saw printmaking as a democratic art form that had an established and international history in mass media. This drew him to Mexico's graphic arts tradition, embodied in its Taller de Gráfica Popular, associated with artists Leopoldo Mendez, Pablo O'Higgins (a close friend of Randall), Francisco Mora, and Elizabeth Catlett. In 1940, Randall worked briefly at the Taller, and he later became an Associate Member.[15] The Taller inspired Randall to establish the co-operative Artist's Guild of San Francisco, in 1945 (serving as President). He served as treasurer of the San Francisco Art Association, and was a member of the San Francisco Artists' Council. In 1947 he became involved in the California Labor School, from which developed San Francisco's Graphic Arts Workshop.[16] Artists of the California Labor School and Graphic Arts Workshop included Victor Arnautoff, Pele deLappe, Louise Gilbert, Lawrence Yamamoto.[17] Members of this leftist circle illustrated the 1948 Communist Manifesto in Pictures, commemorating the Manifesto's centenary with prints by Randall, Giacomo Patri, Robert McChesney, Hassel Smith, Louise Gilbert, Lou Jackson and Bits Hayden.[18]

Randall's commitment to public art at times led him to murals: in the late 1940s he painted a mural for the historic Vesuvio's Café, in San Francisco's North Beach; in 1954, he painted a fresco in a Mexico City public school; in 1957 he painted a mural for the Young Men and Women's Hebrew Association, in Montreal,[19] and in the 60s he assisted his then wife Emmy Lou Packard in creating the Chavez Student Center bas relief mural at Sproul Plaza, UC Berkeley. He also restored Pablo O'Higgins' mural, 1969, in the Honolulu ILWU headquarters. Randall joined forces with prominent artists Mark Rothko, Robert Motherwell, Charles Wilbert White, and Frank Stella, in protesting the Vietnam War.[20] Randall's activism also led him and Packard to the Soviet Union, in 1964, where they had a show of 48 prints in Moscow's Pushkin Museum, which was featured on Soviet television.[21] And it led him, in the mid-1970s, along with artists Mary Fuller, her husband Robert McChesney, and the Sonoma community, to protest against Christo and Jeanne-Claude's Californian Running Fence installation.[22]

Collections

Randall's art is in the permanent collections of

- National Gallery of Art

- Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- Phillips Collection (formerly held)

- Ackland Art Museum

- Albrecht-Kemper Museum of Art

- Art, Design & Architecture Museum

- Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive

- Bolinas Museum

- Centro Cultural de la Raza Archives

- Crocker Art Museum

- Dana–Farber Cancer Institute

- Davis Museum at Wellesley College

- Davison Art Center

- de Saisset Museum

- Fresno Art Museum

- Frost Art Museum

- Georgia Museum of Art

- Grinnell College Museum of Art

- Hallie Ford Museum of Art

- Henry Art Gallery

- Housatonic Museum of Art

- Hunter Museum of American Art

- Janet Turner Print Collection and Gallery, California State University

- Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art

- Jundt Art Museum, Gonzaga University

- Krannert Art Museum

- Long Beach Museum of Art

- Los Angeles Museum of the Holocaust

- Lucas Museum of Narrative Art

- Mariners' Museum

- Mary and Leigh Block Museum of Art

- Maryhill Museum of Art

- Middlebury College Museum of Art

- Mills College Art Museum

- Minneapolis Institute of Art

- Montefiore Medical Center

- Monterey Museum of Art

- Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

- Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec

- Museum of Northwest Art

- Museum of Sonoma County

- Oakland Museum of California

- Palm Springs Art Museum

- Pushkin Museum, Moscow

- Randall Children's Hospital at Legacy Emanuel

- Riverside Art Museum

- Saint Mary's College of California Museum of Art

- San Jose Museum of Art

- Schneider Museum of Art

- Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center

- Smith College Museum of Art

- Swedish Health Services

- Triton Museum of Art

- UC Irvine Institute and Museum for California Art

- University of Michigan Museum of Art

- University of Washington

- Weatherspoon Art Museum

- and Western Art Gallery, Western Washington University.

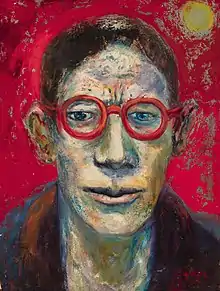

Gallery

Byron Randall, 1959, "Golden Gate Bridge", tempera, private collection

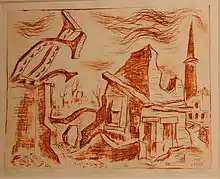

Byron Randall, 1959, "Golden Gate Bridge", tempera, private collection 1947, Diabolical Machine, for 1948 Communist Manifesto in Pictures, Byron Randall

1947, Diabolical Machine, for 1948 Communist Manifesto in Pictures, Byron Randall Byron Randall, "Nada", Tacuba, Mexico series, 1940

Byron Randall, "Nada", Tacuba, Mexico series, 1940 Then There Were None, 1959, Doomsday series (Byron Randall) (Jundt Museum)

Then There Were None, 1959, Doomsday series (Byron Randall) (Jundt Museum) Philo 1964–89, Byron Randall (Private Collection)

Philo 1964–89, Byron Randall (Private Collection) Byron Randall, Mattox, Philo series, 1963–71, private collection

Byron Randall, Mattox, Philo series, 1963–71, private collection Peppers & Honeysuckle, 1993, Byron Randall (Long Beach Museum of Art)

Peppers & Honeysuckle, 1993, Byron Randall (Long Beach Museum of Art) After Rain, Hilo, 1949, Hawaii 1949 serigraph series, Byron Randall

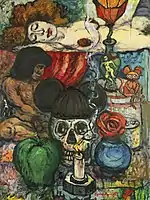

After Rain, Hilo, 1949, Hawaii 1949 serigraph series, Byron Randall Mickey Skull, 1991, Byron Randall

Mickey Skull, 1991, Byron Randall Merchant Marine Shipmates, 1943, Byron Randall (Jundt Museum)

Merchant Marine Shipmates, 1943, Byron Randall (Jundt Museum) Lorraine Almeida, 1989, Byron Randall (Long Beach Museum of Art)

Lorraine Almeida, 1989, Byron Randall (Long Beach Museum of Art) Cow Landscape, Tacuba Mexico 1940, Byron Randall (Private Collection)

Cow Landscape, Tacuba Mexico 1940, Byron Randall (Private Collection) Byron Randall,'Glousterman', Tacuba Mexico 1940 series (Mariners' Museum)

Byron Randall,'Glousterman', Tacuba Mexico 1940 series (Mariners' Museum).jpg.webp) Rainy Night, 1945 linocut by Byron Randall

Rainy Night, 1945 linocut by Byron Randall.jpg.webp) Byron Randall, Balloon Seller, 1990 (American Ethnic Studies Dept, University of Washington)

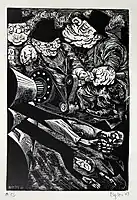

Byron Randall, Balloon Seller, 1990 (American Ethnic Studies Dept, University of Washington) US Stomp Queens, 1968 Woodcut, Beauty Queen series, Byron Randall

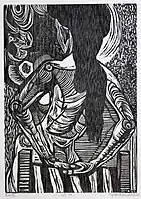

US Stomp Queens, 1968 Woodcut, Beauty Queen series, Byron Randall.jpg.webp) Young Woman, Lodz, 1947, print by Byron Randall (LA Museum of the Holocaust)

Young Woman, Lodz, 1947, print by Byron Randall (LA Museum of the Holocaust) Byron Randall, Wrestlers, 1961

Byron Randall, Wrestlers, 1961 Byron Randall, Man Drying, 1968 Nude woodcut series

Byron Randall, Man Drying, 1968 Nude woodcut series Byron Randall,'Back', Nudes 1968 wood cut series

Byron Randall,'Back', Nudes 1968 wood cut series

See also

References

- "Byron Randall". SFGate. 19 August 1999. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Grieve, Victoria (2009). The Federal Art Project and the Creation of Middlebrow Culture. Urbana: U. of Illinois Press. See also McChesney, Mary Fuller: Oral history interview with Byron Randall. (1964, May 12). Archives of American Art, New Deal and the Arts Oral History Project.

- 'Western Water Colorist: Young Man Goes East and Gets His First Big Showing', Newsweek, Oct. 16, 1939.

- Statesman Journal (Salem, Oregon), Feb 2, 1941, p.12

- Source: the Byron Randall papers, held by Randall's granddaughter Laura Chrisman, manager of the Byron Randall art collection; lhc3@uw.edu. See also Ginny Allen and Jody Klevit, Oregon Painters. Landscape to Modernism, 1859-1959 (Second Edition), Corvallis: Oregon State University Press, 2021.

- Randall, Byron (1947). 'Does Russia Dominate Yugoslavia?'. Soviet Russia Today. Vol 16, no.3 (July).

- 'Artist's Wife Saves Son, Dies Herself', The Gazette (Montreal, Quebec), November 17, 1956, p.3.

- The Press Democrat (Santa Rosa), Feb 24, 1966, p.2

- "Burton Donald Cairns". Pacific Coast Architecture Database (PCAD). Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- Fracchia, Charles A. and Jeremiah O. Bragstad (1976). Converted into Houses. New York: Viking Press.

- The Lewiston Journal, May 2, 1984; The Free Lance-Star, May 3, 1984; The Pittsburgh Press, May 3, 1984; The Milwaukee Sentinel, May 4, 1984.

- deLappe, Pele (2002). A Passionate Journey through Art & the Red Press. Petaluma: s.n.

- "Obituary: Byron Randall". SFGate. 1999-08-19. Retrieved 2019-06-25.

- Byron Randall, Artist's Statement, Salem Art Center show, 1960.

- Makin, Jean, ed. (1999). Codex Mendez. Tempe: Arizona State U. See also Prignitz, Helga (1992). El Taller de Gráfica Popular en México 1937–1977. Mexico: Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes.

- Vogel, Susan (2010). Becoming Pablo O'Higgins. San Francisco/Salt Lake City: Pince-Nez Press.

- Ginger, Ann Fagan and David Christiano (1987). The Cold War Against Labor, vol. one.Berkeley: Meiklejohn Civil Liberties Institute. See also Carlsson, Chris (2011). Ten Years that Shook the City. San Francisco: City Lights Foundation Books.

- Schneiderman, William, intro (1948). Communist Manifesto in Pictures. San Francisco: International Bookstore.

- Gilbert, Dorothy B. (1962). Who's Who in American Art. NY: R.R. Bowker.

- Frascina, Francis (1999). Art, Politics and Dissent. NY: St Martin's Press.

- Packard, Emmy Lou (1964). 'Speaking Out For Peace. Two California artists are exhibited in Pushkin Museum, Moscow'. New World Review, vol. 32, no. 9. (October).

- Chernow, Burt (2002). Christo and Jeanne-Claude. NY: St. Martin's Press.

- Information drawn from museum websites, permanent collection listings, and Deeds of Gift in the Byron Randall papers (held by Laura Chrisman, granddaughter of Randall, manager of the Byron Randall papers and art collection: lhc3@uw.edu).