Frank Stella

Frank Philip Stella (born May 12, 1936) is an American painter, sculptor and printmaker, noted for his work in the areas of minimalism and post-painterly abstraction.[1] Stella lives and works in New York City.

Frank Stella | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Frank Philip Stella May 12, 1936 Malden, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Known for |

|

| Movement | Modernism, minimal art, abstract expressionism, geometric abstraction, abstract illusionism, lyrical abstraction, hard-edge painting, shaped canvas painting, color field painting |

| Awards | 1984 Harvard University Charles Eliot Norton lectures National Medal of Arts |

Biography

Frank Stella was born in Malden, Massachusetts.[2] His father was a gynecologist, and his mother was a housewife and artist who attended fashion school and later took up landscape painting.[3]

After attending high school at Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts,[4] he attended Princeton University. His work was influenced by abstract expressionism.[5] He is heralded for creating abstract paintings that bear no pictorial illusions or psychological or metaphysical references in twentieth-century painting.[6]

In the 1970s he moved into NoHo in Manhattan in New York City.[7] As of 2015, Stella lived in Greenwich Village and kept an office there but commuted on weekdays to his studio in Rock Tavern, New York.[3]

Work

Late 1950s and early 1960s

Upon moving to New York City, he began to produce works which emphasized the picture-as-object.

Stella married Barbara Rose, later a well-known art critic, in 1961. Around this time he said that a picture was "a flat surface with paint on it – nothing more". [citation needed]

Die Fahne Hoch! (1959) takes its name ("The Raised Banner" in English) from the first line of the Horst-Wessel-Lied, the anthem of the National Socialist German Workers Party, and Stella pointed out that it is in the same proportions as banners used by that organization. [citation needed]

In 1959, several of his paintings were included in "Three Young Americans" at the Allen Memorial Art Museum at Oberlin College, as well as in "Sixteen Americans" at the Museum of Modern Art in New York (1960). [citation needed]

From 1960 his works used shaped canvases later developing into more elaborate designs, in the Irregular Polygon series (67), for example. [citation needed]

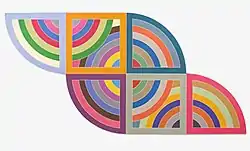

Later he began his Protractor Series (71) of paintings, in which arcs, sometimes overlapping, within square borders named after circular cities he had visited while in the Middle East earlier in the 1960s. [citation needed]

Late 1960s and early 1970s

In 1967, Stella designed the set and costumes for Scramble, a dance piece by Merce Cunningham. [citation needed]

The Museum of Modern Art in New York presented a retrospective of Stella's work in 1970, making him the youngest artist to receive one.[8]

During the following decade, Stella introduced relief, which he came to call "maximalist" painting for its sculptural qualities. [citation needed] After introducing wood and other materials in the Polish Village series (1973), his Minimalism became baroque. In 1976, Stella was commissioned by BMW to paint a BMW 3.0 CSL for the second installment in the BMW Art Car Project. He said of this project, "The starting point for the art cars was racing livery. The graph paper is what it is, a graph, but when it's morphed over the car's forms it becomes interesting. Theoretically it's like painting on a shaped canvas."[9]

In 1969, Stella was commissioned to create a logo for the Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial.[10]

1980s and afterward

_by_Frank_Stella%252C_1984.jpg.webp)

From the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s, Stella created a large body of work that responded in a general way to Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.[11] To create these works, the artist used collages or maquettes that were then enlarged and re-created by assistants[11] (eg. La scienza della pigrizia (The Science of Laziness), from 1984). [citation needed]

In 1993, he created the entire decorative scheme for Toronto’s Princess of Wales Theatre, which includes a 10,000-square-foot mural. [citation needed] In 1997, he oversaw the installation of the 5,000-square-foot "Stella Project" at the Moores Opera House at the Rebecca and John J. Moores School of Music at the University of Houston, in Houston, TX.[12][13] His aluminum bandshell, inspired by a folding hat from Brazil, was built in downtown Miami in 2001. [citation needed] A monumental Stella sculpture was installed outside the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. [citation needed]

Stella's Scarlatti K Series was triggered by the harpsichord sonatas of Domenico Scarlatti.[14]

From 1978 to 2005, Stella owned the Van Tassell and Kearney Horse Auction Mart building in Manhattan's East Village and used it as his studio which resulted in the facade being restored.[15] After a six-year campaign by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation, in 2012 the historic building was designated a New York City Landmark.[16] After 2005, Stella split his time between his West Village apartment and his Newburgh, New York studio.[17]

By the turn of the 2010s, Stella started using the computer as a painterly tool to produce stand-alone star-shaped sculptures.[18] The resulting stars are often monochrome, black or beige or naturally metallic, and their points can take the form of solid planes, spindly lines or wire-mesh circuits.[18] His Jasper’s Split Star (2017), a sculpture constructed out of six small geometric grids that rest on an aluminum base, was installed at 7 World Trade Center in 2021.[19]

Artists' rights

On June 6, 2008, Stella (with Artists Rights Society president Theodore Feder; Stella is a member artist of the Artists Rights Society[20]) published an Op-Ed for The Art Newspaper decrying a proposed U.S. Orphan Works law which "remove[s] the penalty for copyright infringement if the creator of a work, after a diligent search, cannot be located". [citation needed]

In the Op-Ed, Stella wrote,

The Copyright Office presumes that the infringers it would let off the hook would be those who had made a "good faith, reasonably diligent" search for the copyright holder. Unfortunately, it is totally up to the infringer to decide if he has made a good faith search. The Copyright Office proposal would have a disproportionately negative, even catastrophic, impact on the ability of painters and illustrators to make a living from selling copies of their work...[21]

Gallery of works

.jpg.webp) Frank Stella, mural at 'David Mirvish Books', 1974; in Toronto

Frank Stella, mural at 'David Mirvish Books', 1974; in Toronto Stella, detail of BMW 3.0 CLS car-painting, 1976

Stella, detail of BMW 3.0 CLS car-painting, 1976.jpg.webp) Stella, BMW M1 Pro car-painting, 1979; commissioned by Peter Gregg

Stella, BMW M1 Pro car-painting, 1979; commissioned by Peter Gregg.jpg.webp) Stella, Cones and Pillars, part 2., c. 1984; painting

Stella, Cones and Pillars, part 2., c. 1984; painting Stella, Moby Dick, 1991–1993; wall-relief in The Ritz-Carlton, Singapore

Stella, Moby Dick, 1991–1993; wall-relief in The Ritz-Carlton, Singapore Stella, Peekskill, 1995; sculpture of premium steel at Ernst-Abbe-Platz in Jena, Germany

Stella, Peekskill, 1995; sculpture of premium steel at Ernst-Abbe-Platz in Jena, Germany Stella, Cornucopia, c. 2000; sculpture in fiberglass

Stella, Cornucopia, c. 2000; sculpture in fiberglass Stella, Çatal Hüyük, 2008; location, Hallbergsplatsen, Borås

Stella, Çatal Hüyük, 2008; location, Hallbergsplatsen, Borås

Exhibitions

Stella's work was included in several exhibitions in the 1960s, among them the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum’s The Shaped Canvas (1965) and Systemic Painting (1966).[22] The Museum of Modern Art in New York presented a retrospective of Stella's work in 1970.[11]

In 2012, a retrospective of Stella's career was shown at the Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg.[23]

Frank Stella's work Protractor Variation I (1969) is featured in the collections display of the Pérez Art Museum Miami, Florida.[24]

Selected solo exhibitions[25]

- Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, "The Shaped Canvas," New York, NY, December 9–January 3, 1964

- Museum of Modern Art, "Frank Stella," New York, NY, March 26–May 31, 1970

- Phillips Collection, "Frank Stella," Washington, D.C., November 3–December 2, 1973

- Baltimore Museum of Art, "Frank Stella: The Black Paintings," Baltimore, MD, November 23, 1976 – January 23, 1977

- Fort Worth Art Museum, "Stella Since 1970," Fort Worth, TX, March 19–April 30, 1978

- The Museum of Modern Art, "Frank Stella: The Indian Bird Maquettes," New York, NY, March 12–May 1, 1979

- Jewish Museum (Manhattan), "Frank Stella. Polish Wooden Synagogues –Constructions from the 1970s," New York, NY, February 9–May 1, 1983

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, "Resource / Response / Reservoir. Stella Survey 1959-1982," San Francisco, CA, March 10–May 1, 1983

- Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University Art Museum, "Frank Stella: Selected Works," Cambridge, MA, December 7, 1983 – January 26, 1984

- The Museum of Modern Art, "Frank Stella: 1970-1987," New York, NY, October 10, 1987 – January 5, 1988

- Waddington Galleries, "Frank Stella," London, UK, March 29–April 20, 2000

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, "What You See Is What You See: Frank Stella and the Anderson Collection at SFMOMA," San Francisco, CA, June 11–September 6, 2004

- Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard Art Museums, "Frank Stella 1958," Cambridge, MA, February 4–May 7, 2006

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, "Frank Stella: Painting into Architecture," New York, NY, May 1–July 19, 2007

- Neue Nationalgalerie, "Stella & Calatrava. The Michael Kohlhass Curtain," Berlin, Germany, April 15–August 14, 2011

- The Phillips Collection, "Stella Sounds: The Scarlatti K Series," Washington, D.C., June 11 –September 4, 2011

- Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, "Frank Stella. The Retrospective. Works 1958-2012," Wolfsburg, Germany, September 8, 2012 – January 20, 2013

- Royal Academy of Arts, Annenberg Courtyard, "Inflated Star and Wood Star," London, UK, February 18–May 17, 2015

- Whitney Museum of American Art, "Frank Stella: A Retrospective," New York, NY, October 30, 2015 – February 7, 2016

- POLIN Museum of the History of Polish Jews, "Frank Stella and the Synagogues of Old Poland," Warsaw, Poland, February 18–June 20, 2016

- NSU Museum of Art Fort Lauderdale, "Frank Stella: Experiment and Change," Fort Lauderdale, FL, November 11, 2017 – July 29, 2018

- Los Angeles County Museum of Art, "Frank Stella: Selection from the Permanent Collection," Los Angeles, CA, May 5–September 2, 2019

- Marianne Boesky Gallery, "Frank Stella: Recent Work," New York, NY, April 25–May 31, 2019

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology, "Heads or Tails (1988), Cambridge, MA, permanent display[26]

Collections

In 2014, Stella gave his sculpture Adjoeman (2004) as a long-term loan to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles.[27] The Menil Collection, Houston; the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; National Gallery of Art; the Pérez Art Museum Miami;[24] the Toledo Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; the Portland Art Museum, Oregon; the List Visual Arts Center at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge;[26] and many others.[28]

Recognition

Stella gave the Charles Eliot Norton Lectures in 1984, calling for a rejuvenation of abstraction by achieving the depth of baroque painting.[29] These six talks were published by Harvard University Press in 1986 under the title Working Space.[30]

In 2009, Frank Stella was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Barack Obama.[31] In 2011, he received the Lifetime Achievement Award in Contemporary Sculpture by the International Sculpture Center. [citation needed] In 1996, he received an honorary Doctorate from the University of Jena in Jena, (Germany), where his large sculptures of the "Hudson River Valley Series" are on permanent display, becoming the second artist to receive this honorary degree after Auguste Rodin in 1906.[32]

Art market

Since 2014, Stella has been represented worldwide in an exclusive arrangement shared by Dominique Lévy and Marianne Boesky.[33] In May 2019, Christie's set an auction record for Stella's Point of Pines, which sold for $28 million.[34]

In April 2021, his Scramble: Ascending Spectrum/ascending Green Values (1977) was sold for £2.4 million ($3.2 million with premium) in London. The painting was bought for $1.9 million in 2006 from the collection of Belgian art patrons Roger and Josette Vanthournout at Sotheby’s.[35]

Personal life

From 1961-1969 Stella was married to art historian Barbara Rose; they had two children, Rachel and Michael.[36] In 1978 he married pediatrician Harriet McGurk.[37]

Selected bibliography

- Julia M. Busch: A decade of sculpture: the 1960s, Associated University Presses, Plainsboro, 1974; ISBN 0-87982-007-1

- Frank Stella and Siri Engberg: Frank Stella at Tyler Graphics, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 1997; ISBN 9780935640588

- Frank Stella and Franz-Joachim Verspohl: The Writings of Frank Stella. Die Schriften Frank Stellas, Verlag der Buchhandlung König, Cologne, 2001; ISBN 3-88375-487-0, ISBN 978-3-88375-487-1 (bilingual)

- Frank Stella and Franz-Joachim Verspohl: Heinrich von Kleist by Frank Stella, Verlag der Buchhandlung König, Cologne, 2001; ISBN 3-88375-488-9, ISBN 978-3-88375-488-8 (bilingual)

- Andrianna Campbell, Kate Nesin, Lucas Blalock, Terry Richardson: Frank Stella, Phaidon, London, 2017; ISBN 9780714874593

Non-Fungible Tokens

In late 2022, Stella launched an NFT (non-fungible token) that includes the right to the CAD files to 3D print the art works in the NFTs.[38]

References

- "Frank Stella". Waddington Custot.

- "Frank Stella Biography, Art, and Analysis of Works". The Art Story. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Deborah Solomon (September 7, 2015), The Whitney Taps Frank Stella for an Inaugural Retrospective at Its New Home The New York Times.

- Peter Schjeldahl (November 9, 2015), "Big Ideas: a Frank Stella Retrospective", The New Yorker

- "Frank Stella Paintings, Bio, Ideas". The Art Story.

- Birmingham Museum of Art (2010). Birmingham Museum of Art : guide to the collection. [Birmingham, Ala]: Birmingham Museum of Art. p. 236. ISBN 978-1-904832-77-5.

- Kenneth T. Jackson, Lisa Keller, Nancy Flood (2010). The Encyclopedia of New York City, Second Edition, Yale University Press.

- "Frank Stella | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- "Frank Stella | The Art Car: Limited Edition BMW Minichamps of Frank Stella's 1976 Le Mans The Graph Car, Scale 1:18, 3.0 CSL No.21 (2004) | Available for Sale | Artsy". www.artsy.net. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- Finding aid for the George Trescher records related to The Metropolitan Museum of Art Centennial, 1949, 1960–1971 (bulk 1967–1970). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 8, 2014.

- Frank Stella Archived March 22, 2014, at the Wayback Machine Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

- "About the Stella Project in the Moores Opera House". Archived from the original on March 1, 2009.

- "Home". Music.uh.edu. April 25, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2012.

- Karen Wilkin (June 23, 2011), Complementary Abstractionists The Wall Street Journal.

- 128 East 13th Street Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

- "Van Tassell & Kearney Auction Mart Designation Report" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- Sightlines: Frank Stella The Wall Street Journal, March 15, 2010.

- Jason Farago (February 4, 2021), In Frank Stella’s Constellation of Stars, a Perpetual Evolution New York Times.

- M.H. Miller (November 22, 2021), After 20 Years, Frank Stella Returns to Ground Zero New York Times.

- "Artists Rights Society's List of Most Frequently Requested Artists". Archived from the original on February 6, 2015.

- Frank Stella, "The proposed new law is a nightmare for artists," Archived October 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine The Art Newspaper, June 6, 2008.

- "Artist Intro". Heather James. Retrieved August 10, 2021.

- Rhodes, David (November 2012). "Frank Stella: The Retrospective, Works 1958–2012". The Brooklyn Rail.

- "Frank Stella • Pérez Art Museum Miami". Pérez Art Museum Miami. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- "Frank Stella". Marianne Boesky Gallery. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

- "Heads or Tails, 1988 | MIT List Visual Arts Center". listart.mit.edu. January 13, 2022. Retrieved May 30, 2023.

- Deborah Vankin (July 7, 2014), Abstract Frank Stella sculpture 'Adjoeman' joins Cedars-Sinai artworks Los Angeles Times.

- "A Finding Aid to the Frank Stella papers, 1941-1993, bulk 1978-1989 | Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution". www.aaa.si.edu. Retrieved August 29, 2023.

- John Russell (March 18, 1984), Frank Stella at Harvard – The Artist as Lecturer The New York Times.

- Frank Stella, Working Space (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1986), ISBN 0-674-95961-2. Listing at Harvard University Press website.

- White House Announces 2009 National Medal of Arts Recipients Archived May 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Schrotthaufen oder Kunst? Frank Stella in Jena". www.jenanews.de.

- Carol Vogel (March 20, 2014), Seasonal changes New York Times.

- "RESULTS | 20th Century Week Totals $1.072 Billion". Christie's. May 17, 2019.

- Villa, Angelica (April 15, 2021). "$34.2 M. Phillips London Sale Brings Tunji Adeniyi-Jones Record and Air of Optimism". ARTnews.com. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- Solomon, Deborah (December 27, 2020). "Barbara Rose, Critic and Historian of Modern Art, Dies at 84". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- O'Grady, Megan (March 18, 2020). "THE CONSTELLATION OF FRANK STELLA". Retrieved March 23, 2021.

- Levin, Alex. "Frank Stella's New NFTs Come With The Right To Print His Art". Forbes. Retrieved March 9, 2023.

External links

- Frank Stella works at the National Gallery of Art

- Unbounded Doctrine: Encountering the Art-Making Career of Frank Stella ArtsEditor.com, December 29, 2015.

- Frank Stella in the National Gallery of Australia's Kenneth Tyler Collection

- Word Symbol Space An exhibition featuring work by Frank Stella at The Jewish Museum, NY.

- Frank Stella interviewed by Robert Ayers, March 2009

- Works of art, auction & sale results, exhibitions, and artist information for Frank Stella on artnet

- Guggenheim Museum online Biography of Frank Stella

- Stella's work in the Guggenheim Collection Archived October 7, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Stella mural installation, Princess of Wales Theatre, Toronto

- Frank Stella: An Illustrated Biography by Sidney Guberman

- Frank Stella Papers at the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art

- Frank Stella: Scarlatti and Bali Sculpture Series / Paracelsus Building, St. Moritz. Video at VernissageTV.

- Frank Stella 1958 poet William Corbett writes about the exhibition titled Frank Stella 1958 at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts February 4 – May 7, 2006

- Laying the Tracks Others Followed; Early Work at L&M Arts; The New York Times; Roberta Smith; April 26, 2012

- Frank Stella in the Guggenheim collection