Mural

A mural is any piece of graphic artwork that is painted or applied directly to a wall, ceiling or other permanent substrate. Mural techniques include fresco, mosaic, graffiti and marouflage.

Word mural in art

The word mural is a Spanish adjective that is used to refer to what is attached to a wall. The term mural later became a noun. In art, the word mural began to be used at the beginning of the 20th century.

In 1906, Dr. Atl issued a manifesto calling for the development of a monumental public art movement in Mexico; he named it in Spanish pintura mural (English: wall painting).[1]

In ancient Roman times, a mural crown was given to the fighter who was first to scale the wall of a besieged town.[2] "Mural" comes from the Latin muralis, meaning "wall painting". This word is related to murus, meaning "wall".

History

Antique art

Murals of sorts date to Upper Paleolithic times such as the cave paintings in the Lubang Jeriji Saléh cave in Borneo (40,000-52,000 BP), Chauvet Cave in Ardèche department of southern France (around 32,000 BP). Many ancient murals have been found within ancient Egyptian tombs (around 3150 BC),[3] the Minoan palaces (Middle period III of the Neopalatial period, 1700–1600 BC), the Oxtotitlán cave and Juxtlahuaca in Mexico (around 1200-900 BC) and in Pompeii (around 100 BC – AD 79).

During the Middle Ages murals were usually executed on dry plaster (secco). The huge collection of Kerala mural painting dating from the 14th century are examples of fresco secco.[4][5] In Italy, c. 1300, the technique of painting of frescos on wet plaster was reintroduced and led to a significant increase in the quality of mural painting.[6]

Modern art

The term mural became better known with the Mexican muralism art movement (Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros and José Orozco). The first mural painted in the 20th century, was “El árbol de la vida”, by Roberto Montenegro.

There are many different styles and techniques. The best-known is probably fresco, which uses pigments dispersed in water with a damp lime wash, rapid use of the resulting mixture over a large surface, and often in parts (but with a sense of the whole). The colors lighten as they dry. The marouflage method has also been used for millennia.

Murals today are painted in a variety of ways, using oil or water-based media. The styles can vary from abstract to trompe-l'œil (a French term for "fool" or "trick the eye"). Initiated by the works of mural artists like Graham Rust or Rainer Maria Latzke in the 1980s, trompe-l'œil painting has experienced a renaissance in private and public buildings in Europe. Today, the beauty of a wall mural has become much more widely available with a technique whereby a painting or photographic image is transferred to poster paper or canvas which is then pasted to a wall surface (see wallpaper, Frescography) to give the effect of either a hand-painted mural or realistic scene.

A special type of mural painting is Lüftlmalerei, still practised today in the villages of the Alpine valleys. Well-known examples of such façade designs from the 18th and 19th centuries can be found in Mittenwald, Garmisch, Unter- and Oberammergau.

Technique

In the history of mural several methods have been used:

A fresco painting, from the Italian word affresco which derives from the adjective fresco ("fresh"), describes a method in which the paint is applied on plaster on walls or ceilings.

The buon fresco technique consists of painting in pigment mixed with water on a thin layer of wet, fresh, lime mortar or plaster. The pigment is then absorbed by the wet plaster; after a number of hours, the plaster dries and reacts with the air: it is this chemical reaction which fixes the pigment particles in the plaster. After this the painting stays for a long time up to centuries in fresh and brilliant colors.

Fresco-secco painting is done on dry plaster (secco is "dry" in Italian). The pigments thus require a binding medium, such as egg (tempera), glue or oil to attach the pigment to the wall.

Mezzo-fresco is painted on nearly-dry plaster, and was defined by the sixteenth-century author Ignazio Pozzo as "firm enough not to take a thumb-print" so that the pigment only penetrates slightly into the plaster. By the end of the sixteenth century this had largely displaced the buon fresco method, and was used by painters such as Gianbattista Tiepolo or Michelangelo. This technique had, in reduced form, the advantages of a secco work.

Material

In Greco-Roman times, mostly encaustic colors applied in a cold state were used.[7][8]

Tempera painting is one of the oldest known methods in mural painting. In tempera, the pigments are bound in an albuminous medium such as egg yolk or egg white diluted in water.

In 16th-century Europe, oil painting on canvas arose as an easier method for mural painting. The advantage was that the artwork could be completed in the artist's studio and later transported to its destination and there attached to the wall or ceiling. Oil paint may be a less satisfactory medium for murals because of its lack of brilliance in colour. Also, the pigments are yellowed by the binder or are more easily affected by atmospheric conditions.

Different muralists tend to become experts in their preferred medium and application, whether that be oil paints, emulsion or acrylic paints[9] applied by brush, roller or airbrush/aerosols. Clients will often ask for a particular style and the artist may adjust to the appropriate technique.[10]

A consultation usually leads to detailed design and layout of the proposed mural with a price quote that the client approves before the muralist starts on the work. The area to be painted can be gridded to match the design allowing the image to be scaled accurately step by step. In some cases, the design is projected straight onto the wall and traced with pencil before painting begins. Some muralists will paint directly without any prior sketching, preferring the spontaneous technique.

Once completed the mural can be given coats of varnish or protective acrylic glaze to protect the work from UV rays and surface damage.

In modern, quick form of muralling, young enthusiasts also use POP clay mixed with glue or bond to give desired models on canvas board. The canvas is later set aside to let the clay dry. Once dried, the canvas and the shape can be painted with your choice of colors and later coated with varnish.

As an alternative to a hand-painted or airbrushed mural, digitally printed murals can also be applied to surfaces. Already existing murals can be photographed and then be reproduced in near-to-original quality.

The disadvantages of pre-fabricated murals and decals are that they are often mass-produced and lack the allure and exclusivity of original artwork. They are often not fitted to the individual wall sizes of the client and their personal ideas or wishes cannot be added to the mural as it progresses. The Frescography technique, a digital manufacturing method (CAM) invented by Rainer Maria Latzke addresses some of the personalisation and size restrictions.

Digital techniques are commonly used in advertisements. A "wallscape" is a large advertisement on or attached to the outside wall of a building. Wallscapes can be painted directly on the wall as a mural, or printed on vinyl and securely attached to the wall in the manner of a billboard. Although not strictly classed as murals, large scale printed media are often referred to as such. Advertising murals were traditionally painted onto buildings and shops by sign-writers, later as large scale poster billboards.

Significance

Murals are important as they bring art into the public sphere. Due to the size, cost, and work involved in creating a mural, muralists must often be commissioned by a sponsor. Often it is the local government or a business, but many murals have been paid for with grants of patronage. For artists, their work gets a wide audience who otherwise might not set foot in an art gallery. A city benefits by the beauty of a work of art.

Murals can be a relatively effective tool of social emancipation or achieving a political goal.[11] Murals have sometimes been created against the law, or have been commissioned by local bars and coffee shops. Often, the visual effects are an enticement to attract public attention to social issues. State-sponsored public art expressions, particularly murals, are often used by totalitarian regimes as a tool of propaganda. However, despite the propagandist character of that works, some of them still have an artistic value.

Murals can have a dramatic impact whether consciously or subconsciously on the attitudes of passers-by, when they are added to areas where people live and work. It can also be argued that the presence of large, public murals can add aesthetic improvement to the daily lives of residents or that of employees at a corporate venue. Large-format hand-painted murals were the norm for advertisements in cities across America, before the introduction of vinyl and digital posters. It was an expensive form of advertising with strict signage laws but gained attention and improved local aesthetics.[12]

Other world-famous murals can be found in Mexico, New York City, Philadelphia, Belfast, Derry, Los Angeles, Nicaragua, Cuba, the Philippines, and in India. They have functioned as an important means of communication for members of socially, ethnically and racially divided communities in times of conflict. They also proved to be an effective tool in establishing a dialogue and hence solving the cleavage in the long run. The Indian state Kerala has exclusive murals. These Kerala mural painting are on walls of Hindu temples. They can be dated from 9th century AD.

The San Bartolo murals of the Maya civilization in Guatemala, are the oldest example of this art in Mesoamerica and are dated at 300 BC.

Many rural towns have begun using murals to create tourist attractions in order to boost economic income. Colquitt, Georgia was chosen to host the 2010 Global Mural Conference. The town had more than twelve murals completed, and hosted the Conference along with Dothan, Alabama, and Blakely, Georgia.

Politics

The Bardia Mural, photographed in the 1960s, prior to its damage by defacement and the ravages of time.

The Bardia Mural, photographed in the 1960s, prior to its damage by defacement and the ravages of time. Murals displaying the Marxist view of the press on this East Berlin cafe in 1977 were covered over by commercial advertising after Germany was reunited.

Murals displaying the Marxist view of the press on this East Berlin cafe in 1977 were covered over by commercial advertising after Germany was reunited. A mural with Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump in Vienna.

A mural with Kim Jong Un and Donald Trump in Vienna.

The Mexican mural movement in the 1930s brought new prominence to murals as a social and political tool. Diego Rivera, José Orozco and David Siqueiros were the most famous artists of the movement. Between 1932 and 1940, Rivera also painted murals in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York City. In 1933, he completed a famous series of twenty-seven fresco panels entitled Detroit Industry on the walls of an inner court at the Detroit Institute of Arts.[13] During the McCarthyism of the 1950s, a large sign was placed in the courtyard defending the artistic merit of the murals while attacking his politics as "detestable".

In 1948, the Colombian government hosted the IX Pan-American Conference to establish the Marshall plan for the Americas. The director of the OEA and the Colombian government commissioned master Santiago Martinez Delgado, to paint a mural in the Colombian congress building to commemorate the event. Martinez decided to make it about the Cúcuta Congress, and painted Bolívar in front of Santander, making liberals upset; so, due to the murder of Jorge Elieser Gaitan the mobs of el bogotazo tried to burn the capitol, but the Colombian Army stopped them. Years later, in the 1980s, with liberals in charge of the Congress, they passed a resolution to turn the whole chamber in the Elliptic Room 90 degrees to put the main mural on the side and commissioned Alejandro Obregon to paint a non-partisan mural in the surrealist style.

Northern Ireland contains some of the most famous political murals in the world.[14] Almost 2,000 murals have been documented in Northern Ireland since the 1970s.[15] In recent times, many murals are non-sectarian, concerning political and social issues such as racism and environmentalism, and many are completely apolitical, depicting children at play and scenes from everyday life. (See Northern Irish murals.)

A not political, but social related mural covers a wall in an old building, once a prison, at the top of a cliff in Bardiyah, in Libya. It was painted and signed by the artist in April 1942, weeks before his death on the first day of the First Battle of El Alamein. Known as the Bardia Mural, it was created by English artist, private John Frederick Brill.[16]

In 1961 East Germany began to erect a wall between East and West Berlin, which became famous as the Berlin Wall. While on the East Berlin side painting was not allowed, artists painted on the Western side of the Wall from the 80s until the fall of the Wall in 1989.

Many unknown and known artists such as Thierry Noir and Keith Haring painted on the Wall, the "World's longest canvas". The sometimes detailed artwork were often painted over within hours or days. On the Western side the Wall was not protected, so everybody could paint on the Wall. After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the Eastern side of the Wall became also a popular "canvas" for many mural and graffiti artists. Orgosolo, in Sardinia, is a most important center of murals politics.

It is also common for mural graffiti to be used as a memoir. In the 2001 book Somebody Told Me, Rick Bragg writes about a series of communities, mainly located in New York, that have walls dedicated to the people who died.[17] These memorials, both written word and mural style, provide the deceased to be present in the communities in which they lived. Bragg states that the "murals have woven themselves in the fabric of the neighborhoods, and the city". These memorials remind people of the deaths caused by inner city violence.

Contemporary interior design

Traditional

Many people like to express their individuality by commissioning an artist to paint a mural in their home. This is not an activity exclusively for owners of large houses. A mural artist is only limited by the fee and therefore the time spent on the painting; dictating the level of detail; a simple mural can be added to the smallest of walls.

Private commissions can be for dining rooms, bathrooms, living rooms or, as is often the case- children's bedrooms. A child's room can be transformed into the 'fantasy world' of a forest or racing track, encouraging imaginative play and an awareness of art.

The current trend for feature walls has increased commissions for muralists in the UK. A large hand-painted mural can be designed on a specific theme, incorporate personal images and elements and may be altered during the course of painting it. The personal interaction between client and muralist is often a unique experience for an individual not usually involved in the arts.

In the 1980s, illusionary wall painting experienced a renaissance in private homes. The reason for this revival in interior design could, in some cases be attributed to the reduction in living space for the individual. Faux architectural features, as well as natural scenery and views, can have the effect of 'opening out' the walls. Densely built-up areas of housing may also contribute to people's feelings of being cut off from nature in its free form. A mural commission of this sort may be an attempt by some people to re-establish a balance with nature.

Commissions of murals in schools, hospitals, and retirement homes can achieve a pleasing and welcoming atmosphere in these caring institutions. Murals in other public buildings, such as public houses are also common.

Graffiti-style

Recently, graffiti and street art have played a key role in contemporary wall painting. Such graffiti/street artists as Keith Haring, Shepard Fairey, Above, Mint&Serf, Futura 2000, Os Gemeos, and Faile among others have successfully transcended their street art aesthetic beyond the walls of urban landscape and onto walls of private and corporate clients. As graffiti/street art became more mainstream in the late 1990s, youth-oriented brands such as Nike and Red Bull, with Wieden Kennedy, have turned to graffiti/street artists to decorate walls of their respective offices. This trend continued through 2000's with graffiti/street art gaining more recognition from art institutions worldwide.

Ethnic

Many homeowners choose to display the traditional art and culture of their society or events from their history in their homes. Ethnic murals have become an important form of interior decoration. Warli painting murals are becoming a preferred mode of wall decor in India. Warli painting is an ancient Indian art form in which the tribal people used to depict different phases of their life on the walls of their mud houses.

Tile

Tile murals are murals made out of stone, ceramic, porcelain, glass and or metal tiles that are installed within, or added onto the surface of an existing wall. They are also inlaid into floors. Mural tiles are painted, glazed, sublimation printed (as described below) or more traditionally cut out of stone, ceramic, mosaic glass(opaque) and stained glass. Some artists use pottery and plates broken into pieces. Unlike the traditional painted murals described above, tile murals are always made by fitting pieces of the selected materials together to create the design or image.

Mosaic murals are made by combining small 1/4" to 2" size pieces of colorful stone, ceramic, or glass tiles which are then laid out to create a picture. Modern day technology has allowed commercial mosaic mural makers to use computer programs to separate photographs into colors that are automatically cut and glued onto sheets of mesh creating precise murals fast and in large quantities.

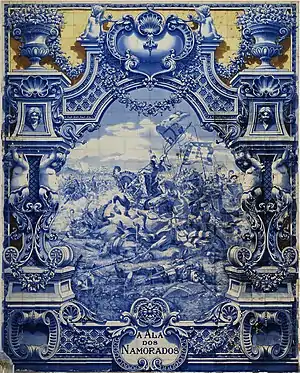

The azulejo (Portuguese pronunciation: [ɐzuˈleʒu], Spanish pronunciation: [aθuˈlexo]) refers to a typical form of Portuguese or Spanish painted, tin-glazed, ceramic tilework. They have become a typical aspect of Portuguese culture, manifesting without interruption during five centuries, the consecutive trends in art.

Azulejos can be found inside and outside churches, palaces, ordinary houses and even railway stations or subway stations.

They were not only used as an ornamental art form, but also had a specific functional capacity like temperature control in homes. Many azulejos chronicle major historical and cultural aspects of Portuguese history.

Custom-printed tile murals can be produced using digital images for kitchen splashbacks, wall displays, and flooring. Digital photos and artwork can be resized and printed to accommodate the desired size for the area to be decorated. Custom tile printing uses a variety of techniques including dye sublimation and ceramic-type laser toners. The latter technique can yield fade-resistant custom tiles which are suitable for long term exterior exposure.

Notable muralists

- Edwin Abbey

- Carlos Almaraz

- Dorothy Annan

- Judy Baca

- Banksy

- Above (artist)

- Arnold Belkin

- Thomas Hart Benton

- John T. Biggers

- Torsten Billman

- Henry Bird

- Edwin Howland Blashfield

- Blek le Rat

- Giotto di Bondone

- Guillaume Bottazzi

- Gabriel Bracho

- Arturo Garcia Bustos

- Paul Cadmus

- Eleanor Coen

- Dean Cornwell

- Kenyon Cox

- John Steuart Curry

- Robert Dafford

- Dora De Larios

- Santiago Martinez Delgado

- Faile

- Shepard Fairey

- LeRoy Foster

- Piero della Francesca

- Carlos "Botong" Francisco

- Os Gemeos

- Louis Grell

- Satish Gujral

- Manav Gupta

- Richard Haas

- Keith Haring

- Jane Kim (artist)

- Eduardo Kobra

- Albert Henry Krehbiel

- Susan Krieg

- Per Krohg

- Paul Kuniholm

- Rainer Maria Latzke

- Rina Lazo

- Tom Lea

- Michelle Loughery

- Will Hicok Low

- Sofia Maldonado

- John Anton Mallin

- Andrea Mantegna

- Reginald Marsh

- Knox Martin

- Peter Max

- Anjolie Ela Menon

- Michelangelo

- Mario Miranda

- Claude Monet

- Roberto Montenegro

- Frank Nuderscher

- Violet Oakley

- Edward O'Brien

- Juan O'Gorman

- Pablo O'Higgins

- José Clemente Orozco

- Rufus Porter

- Aarón Piña Mora

- John Pugh

- Archie Rand

- Raphael

- Diego Rivera

- Graham Rust

- P K Sadanandan

- Sadequain

- John Singer Sargent

- Eugene Savage

- Conrad Schmitt

- Clément Serveau

- David Alfaro Siqueiros

- Frank Stella

- Rufino Tamayo

- Titian

- Alton Tobey

- Allen Tupper True

- Kent Twitchell

- Leonardo da Vinci

- John Augustus Walker

- Henry Oliver Walker

- Lucia Wiley

- Ezra Winter

- Lumen Martin Winter

- Richard Wyatt, Jr.

- Robert Wyland

- Isaiah Zagar

- Carolina Falkholt

Gallery

Wall paint, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Wall paint, Dhaka, Bangladesh Graffiti mural in Gutovka, Prague 10, Czech Republic, 2012

Graffiti mural in Gutovka, Prague 10, Czech Republic, 2012 Orr C. Fischer, The Corn Parade, 1941, oil on canvas, Agriculture-themed mural on wall of post office, Mount Ayr, Iowa[18]

Orr C. Fischer, The Corn Parade, 1941, oil on canvas, Agriculture-themed mural on wall of post office, Mount Ayr, Iowa[18] Mural on Israeli separation barrier

Mural on Israeli separation barrier.jpg.webp)

a school project funded by the government of Angola so that the kids can paint this mural. Each school painted one

a school project funded by the government of Angola so that the kids can paint this mural. Each school painted one_corr.jpg.webp)

See also

- Anamorphosis

- Bogside Artists

- Brixton murals

- Detachment of wall paintings

- Institute of Mural Painting

- List of New Deal murals

- List of United States post office murals

- Mexican muralism

- Murals of Kerala, India

- MURAL Festival

- Newtown area graffiti and street art

- Post Office Murals

- Propaganda

- Public art

- Social realism

- Socialist realism

- The Manchester Murals

- Tiled printing

- Trompe-l'œil

- Wall poems in Leiden

References

- D. Anthony White, Siqueiros, Biography of a Revolutionary Artist, Book Surge, 2009, pp. 19-21

- "MURAL CROWN | Meaning & Definition for UK English | Lexico.com". Archived from the original on March 3, 2021.

- Only after 664 BC are dates secure. See Egyptian chronology for details."Chronology". Digital Egypt for Universities, University College London. Retrieved 2008-03-25.

- Menachery, George (ed.): The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India, Vol. II, 1973; Menachery, George (ed.): Indian Church History Classics, Vol. I, The Nazranies, Saras, 1998

- "Pallikalile Chitrabhasangal" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-06-20.

- "Péter Bokody, Mural Painting as a Medium: Technique, Representation and Liturgy, in Image and Christianity: Visual Media in the Middle Ages, Pannonhalma Abbey, 2014, 136-151". Archived from the original on 2021-04-27. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- Selim Augusti. La tecnica dell'antica pittura parietale pompeiana. Pompeiana, Studi per il 2° Centenario degli Scavi di Pompei. Napoli 1950, 313-354

- Jorge Cuní; Pedro Cuní; Brielle Eisen; Rubén Savizki; John Bové (2012). "Characterization of the binding medium used in Roman encaustic paintings on wall and wood". Analytical Methods. 4 (3): 659. doi:10.1039/C2AY05635F.

- "As used by Eric Cumini Murals". Eric Cumini. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- "Toronto Mural Painting". Technical aspects of mural painting. Toronto Muralists. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Sebastián Vargas. "Seizing public space". D+C, development and cooperation. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- Jamie Lauren Keiles (January 29, 2018). "Hipster Culture and Instagram Are Responsible for a Good Thing". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 November 2019.

- "Diego Rivera". Olga's Gallery. Retrieved 2007-09-24.

- Maximilian Rapp and Markus Rhomberg: Seeking a Neutral Identity in Northern Ireland´s Political Wall Paintings. In: Peace review 24(4).

- Maximilian Rapp and Markus Rhomberg: The importance of Murals during the Troubles: Analyzing the republican use of wall paintings in Northern Ireland. In: Machin, D. (Ed.) Visual Communication Reader. De Gruyter.

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission. "Last Resting Place". Retrieved 29 May 2006.

- Bragg, Rick. Somebody Told Me: The Newspaper Stories of Rick Bragg. New York: Vintage Books, 2001.

- "The Corn Parade". History Matters. George Mason University. Retrieved 27 August 2010.

Further reading

- Campbell, Bruce (2003). Mexican Murals in times of Crisis. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-2239-1.

- Folgarait, Leonard (1998). Mural Painting and Social Revolution in Mexico, 1920-1940: Art of the New Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-58147-8.

- Rouse, E. Clive (1996). Mediaeval Wall Paintings. Guildhall: Shire Publications.

- Woods, Oona (1995). Seeing is Believing? Murals in Derry. Guildhall: Printing Press. ISBN 0-946451-31-1.

- Latzke, Rainer Maria (1999). Dreamworlds- The making of a room with illusionary painting. Monte Carlo Art Edition. ISBN 978-3-00-027990-4.

- Rubanu, Pietrina (1998). Murales politici della Sardegna : guida, storia, percorsi. Massari Editore. ISBN 8845701018.

External links

- How to prepare a mural wall and protect the mural

- Political Wall Murals in Northern Ireland

- Calpams

- Murals.trompe-l-oeil.info French and European gate of murals: 10 000 pictures and 1100 murals

- The National Society of Mural Painters (USA; founded 1895)

- Ancient Maya Art

- Ancient Prehispanic Murals

- Global Murals Conference 2006 at Prestoungrange

- The Melville Shoe Mosaic, an early 20th century ceramic tile mural at 44 Hammond Street in Worcester, MA

- Take an online tour of the murals in Belfast, Northern Ireland

- Albert Krehbiel's murals at the Illinois Supreme Court Building: The Third Branch - A Chronicle of the Illinois Supreme Court; The History of the Illinois Supreme Court

- Murals of Northern Ireland in the Claremont Colleges Digital Library

- Roman wall paintings

- Pixel Mural - A digital mural of collaborative pixel art

- mural.ch / muralism.info Universal database on modern muralism, with many details to the works: authors, locations, literature etc.

- Creative Wall Painting Urban Square Mall, Udaipur created World's Largest and Longest Indoor Paintings honored by World Records India