Intelligence cycle management

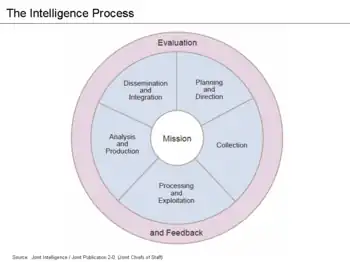

Intelligence cycle management refers to the overall activity of guiding the intelligence cycle, which is a set of processes used to provide decision-useful information (intelligence) to leaders. The cycle consists of several processes, including planning and direction (the focus of this article), collection, processing and exploitation, analysis and production, and dissemination and integration. The related field of counterintelligence is tasked with impeding the intelligence efforts of others. Intelligence organizations are not infallible (intelligence reports are often referred to as "estimates," and often include measures of confidence and reliability) but, when properly managed and tasked, can be among the most valuable tools of management and government.

The principles of intelligence have been discussed and developed from the earliest writers on warfare[1] to the most recent writers on technology.[2] Despite the most powerful computers, the human mind remains at the core of intelligence, discerning patterns and extracting meaning from a flood of correct, incorrect, and sometimes deliberately misleading information (also known as disinformation).

Overview

Intelligence defined

By "intelligence" we mean every sort of information about the enemy and his country—the basis, in short, of our own plans and operations.

Carl Von Clausewitz - On War - 1832

One study of analytic culture[3] established the following "consensus" definitions:

- Intelligence is secret state or group activity to understand or influence foreign or domestic entities.

- Intelligence analysis is the application of individual and collective cognitive methods to weigh data and test hypotheses within a secret socio-cultural context.

- Intelligence errors are factual inaccuracies in analysis resulting from poor or missing data. Intelligence failure is systemic organizational surprise resulting from incorrect, missing, discarded, or inadequate hypotheses.

Management of the intelligence cycle

One basic model of the intelligence process is called the "intelligence cycle". This model can be applied[4] and, like all basic models, it does not reflect the fullness of real-world operations. Intelligence is processed information. The activities of the intelligence cycle obtain and assemble information, convert it into intelligence and make it available to its users. The intelligence cycle comprises five phases:

- Planning and Direction: Deciding what is to be monitored and analyzed. In intelligence usage, the determination of intelligence requirements, development of appropriate intelligence architecture, preparation of a collection plan, issuance of orders and requests to information collection agencies.

- Collection: Obtaining raw information using a variety of collection disciplines such as human intelligence (HUMINT), geospatial intelligence (GEOINT) and others.

- Processing: Refining and analyzing the information

- Analysis and production: The data that has been processed is translated into a finished intelligence product, which includes integrating, collating, evaluating, and analyzing all the data.

- Dissemination: Providing the results of processing to consumers (including those in the intelligence community), including the use of intelligence information in net assessment and strategic gaming.

A distinct intelligence officer is often entrusted with managing each level of the process.

In some organisations, such as the UK military, these phases are reduced to four, with the "analysis and production" being incorporated into the "processing" phase. These phases describe the minimum process of intelligence, but several other activities also come into play. The output of the intelligence cycle, if accepted, drives operations, which, in turn, produces new material to enter another iteration of the intelligence cycle. Consumers give the intelligence organization broad directions, and the highest level sets budgets.

Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) describes an activity that synchronizes and integrates the planning and operation of sensors, assets, and processing, exploitation, and dissemination systems in direct support of current and future operations. This is an integrated intelligence and operations function.[5]

Sensors (people or systems) collect data from the operational environment during the collection phase, which is then converted into information during the processing and exploitation phase. During the analysis and production phase, the information is converted into intelligence.[5]

Planning and direction overview

The planning and direction phase of the intelligence cycle includes four major steps:

- Identification and prioritization of intelligence requirements;

- Development of appropriate intelligence architecture;

- Preparation of a collection plan; and

- Issuance of orders and requests to information collection agencies.[5]

The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff described planning & direction in 2013 as: "...the development of intelligence plans and the continuous management of their execution. Planning and direction activities include, but are not limited to: the identification and prioritization of intelligence requirements; the development of concepts of intelligence operations and architectures required to support the commander’s mission; tasking subordinate intelligence elements for the collection of information or the production of finished intelligence; submitting requests for additional capabilities to higher headquarters; and submitting requests for collection, exploitation, or all-source production support to external, supporting intelligence entities."[5]

Requirements

Leaders with specific objectives communicate their requirements for intelligence inputs to applicable agencies or contacts. An intelligence "consumer" might be an infantry officer who needs to know what is on the other side of the next hill, a head of government who wants to know the probability that a foreign leader will go to war over a certain point, a corporate executive who wants to know what his or her competitors are planning, or any person or organization (for example, a person who wants to know if his or her spouse is faithful).

National/strategic

"Establishing the intelligence requirements of the policy-makers ... is management of the entire intelligence cycle, from identifying the need for data to delivering an intelligence product to a consumer," according to a 2007 report by the U.S. Intelligence Board. "It is the beginning and the end of the cycle—the beginning because it involves drawing up specific collection requirements and the end because finished intelligence, which supports policy decisions, generates new requirements."[6]

"The whole process depends on guidance from public officials. Policy-makers—the president, his aides, the National Security Council, and other major departments and agencies of government—initiate requests for intelligence. Issue coordinators interact with these public officials to establish their core concerns and related information requirements. These needs are then used to guide collection strategies and the production of appropriate intelligence products".[6]

Military/operational

Intelligence requirements are determined by the commander to support his operational needs. The commander's requirement, sometimes called "essential elements of intelligence" (EEIs), initiates the intelligence cycle. Operational and tactical intelligence always should help the commander select an action.

Each intelligence source has different characteristics that can be used, but which may also be limiting. Imagery intelligence (IMINT), for instance, may depend on weather, satellite orbits or the ability of aircraft to elude ground defenses, and time for analysis. Other sources may take considerable time to collect the necessary information. Measurement and signature intelligence (MASINT) depends on having built a library of signatures of normal sensor readings, in order that deviations will stand out.

In rare cases, intelligence is taken from such extremely sensitive sources that it cannot be used without exposing the methods or persons providing such intelligence. One of the strengths of the British penetration of the German Enigma cryptosystem was that no information learned from it was ever used for operations, unless there was a plausible cover story that the Germans believed was the reason for Allied victories. If, for example, the movement of a ship was learned through Enigma COMINT, a reconnaissance aircraft was sent into the same area, and allowed to be seen by the Axis, so they thought the resulting sinking was due to IMINT.

Intelligence architecture

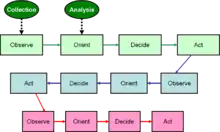

The intelligence cycle is only a model. Budgetary and policy direction are hierarchically above it. In reality, it is not a cycle, but a series of parallel activities. According to Arthur S. Hulnick, author of What's Wrong with the Intelligence Cycle, "Collection and analysis, which are supposed to work in tandem, in fact work more properly in parallel. Finally, the idea that decision-makers wait for the delivery of intelligence before making policy decisions is equally incorrect. In the modern era, policy officials seem to want intelligence to support policy rather than to inform it. The Intelligence Cycle also fails to consider either counterintelligence or covert action.[7]" The OODA loop developed by military strategist John Boyd, discussed in the context of the Intelligence Cycle, may come somewhat closer, as OODA is action-oriented and spiraling, rather than a continuing circle.

Budgeting

The architectural design must then be funded. While each nation has its own budgeting process, the major divisions of the US process are representative:

- National intelligence, often excluding specifically national-level military intelligence,

- National-level military intelligence,

- Military tactical intelligence,

- Transnational intelligence, often involving law enforcement, for terrorism and organized crime, and

- Internal counterintelligence and antiterrorism.

Depending on the nation, at some level of detail, budgetary information will be classified, as changes in budget indicate changes in priorities. After considerable debate, the U.S. now publishes total budgets for the combination of its intelligence agencies. Depending on the sensitivity of a line item, it may be identified simply as "classified activity,"not broken out, but briefed to full oversight committees, or only revealed to a small number of officials.

"It should be possible to empower a committee composed of mid-level officials (or aides to senior officials) from the intelligence and policy-making communities to convene regularly to determine and revise priorities. The key is to try to get policymakers to provide guidance for both collection and analysis, to communicate not just what they want but also what they do not."

The CFR proposed a "market constraint" on consumers, in which they could only get a certain amount of intelligence from the intelligence community, before they had to provide additional funding.[8] A different constraint would be that an agency, to get information on a new topic, must agree to stop or reduce coverage on something currently being monitored for it. Even with this consumer-oriented model, the intelligence community itself needs to have a certain amount of resources that it can direct itself, for building basic intelligence and identifying unusual threats.

"It is important that intelligence officers involved in articulating requirements represent both analysts and collectors, including those from the clandestine side. In addition, collection should be affected by the needs of policymakers and operators. All of this argues strongly against any organizational reforms that would isolate the collection agencies further or increase their autonomy."

Especially in nations with advanced technical sensors, there is an interaction between budgeting and technology. For example, the US has tended, in recent years, to use billion-dollar SIGINT satellites, where France has used "swarms" of "microsatellites". The quantity versus quality battle is as evident in intelligence technology as in weapons systems. The U.S. has fought a stovepipe battle, in which SIGINT and IMINT satellites, in a given orbit, were launched by different agencies. New plans put SIGINT, MASINT, and IMINT sensors, corresponding to a type of orbit, on common platforms.

Policy factors

Western governments tend to have creative tension among their law enforcement and national security organizations, foreign-oriented versus domestic-oriented organizations, and public versus private interests. There is frequently a conflict between clandestine intelligence and covert action, which may compete for resources in the same organization.

Balancing law enforcement and national security

There is an opposition between law enforcement and intelligence, because the two entities are very different. Intelligence is oriented toward the future and seeks to inform policy-makers. It lives in an area of uncertainty where the truth may be uncertain. Because intelligence strives to protect its sources and methods, intelligence officials seek to stay out of the chain of evidence so they will not have to testify in court. By contrast, law enforcement's business is the prosecution of cases, and if law enforcement is to make a case, it must be prepared to reveal how it knows what it knows.

The Council on Foreign Relations[8] recommended that "foreign policy ought to take precedence over law enforcement when it comes to overseas operations. The bulk of U.S. intelligence efforts overseas are devoted to traditional national security concerns; as a result, law enforcement must ordinarily be a secondary concern. FBI and DEA agents operating abroad should not be allowed to act independently of either the ambassador or the CIA lest pursuit of evidence or individuals for prosecution cause major foreign policy problems or complicate ongoing intelligence and diplomatic activities. (The same should hold for any Defense Department personnel involved in intelligence activity overseas.) There are likely to be exceptions, and a degree of case-by-case decision-making will be inevitable. What is needed most is a Washington-based interagency mechanism involving officials from intelligence, law enforcement, and foreign policy to sort out individual cases. One now exists; the challenge is to make it work.

"At home, law enforcement should have priority and the intelligence community should continue to face restraints in what it can do vis-à-vis American citizens." The protection of civil liberties remains essential. National organizations intended for foreign operations, or military support, should operate within the home country only under specific authorization and when there is no other way to achieve the desired result ... Regardless, the ability of intelligence agencies to give law enforcement incidentally acquired information on U.S. citizens at home or overseas ought to be continued. There should be no prohibition (other than those based on policy) on the intelligence community collecting information against foreign persons or entities. The question of what to do with the information, however, should be put before policymakers if it raises foreign policy concerns.[8]

President Harry S. Truman had legitimate concerns about creating a "Gestapo," so he insisted that the new CIA not have law enforcement or domestic authority. In an era of transnational terrorism and organized crime, there may not be clean distinctions between domestic and foreign activities.[9]

Public versus private

"During the Cold War, national security was a federal government monopoly. To be sure, private citizens and corporations were involved, but there was a neat correspondence between the threat as defined and the federal government's national security machinery that was developed to meet that threat.

The war against terrorism and homeland security will be much less a federal government monopoly. Citizens of democracies and the economy are already suffering the inconvenience and higher business costs of much tighter security. And tragically, more ordinary citizens are likely to die from transnational terrorism."[10]

Public and private interests can both complement and conflict when it comes to economic intelligence. Multination corporations usually have a form of capable intelligence capabilities in their core business. Lloyd's of London has extensive knowledge of maritime affairs. Oil companies have extensive information on world resources and energy demands. Investment banks can track capital flow.

These intelligence capabilities become especially difficult when private organizations seek to use national capabilities for their private benefit. Sometimes, a quid pro quo may be involved. Secret economic information can be collected by several means-mostly SIGINT and HUMINT. The more sensitive reconnaissance satellites may not be needed to get substantially correct imagery. Earth resources satellites may give adequate, or even better detail—reconnaissance satellites tend not to have the multispectral scanners that are best for agricultural or other economic information.

The private sector may already have good information on trade policy, resources, foreign exchange, and other economic factors. This may not be "open source" in the sense of being published, but can be reliably bought from research firms that may not have the overhead of all-source security. The intelligence agencies can use their all-source capability for verification, rather than original collection. Intelligence agencies, working with national economic and diplomatic employees, can develop policy alternatives for negotiators.

One subtle aspect of the role of economic intelligence is the interdependence of the continental and world economies. The economic health of Mexico clearly affects the United States, just as the Turkish economy is of concern to the European Community. In a post-Cold War environment, the roles of Russia and China are still evolving. Japan, with a history of blurred lines between industry and government, may regard a policy (for them) as perfectly ethical, which would be questionable in North America or Eastern Europe. New groupings such as the Shanghai Cooperative Organization are principally economic. Economic measures also may be used to pressure specific countries—for example, South Africa while it sustained a policy of apartheid, or Sudan while there is widespread persecution in Darfur.

Collection planning

Collection planning matches anticipated collection requirements with collection capabilities at multiple organizational levels (e.g., national, geographic theater, or specific military entities). It is a continuous process that coordinates and integrates the efforts of all collection units and agencies. This multi-level collaboration helps identify collection gaps and redundant coverage in a timely manner to optimize the employment of all available collection capabilities.[5]

CCIRM

The collection coordination intelligence requirements management (CCIRM) system is the NATO doctrine for intelligence collection management, although it differs from U.S. doctrine.[11] From the U.S. perspective, CCIRM manages requests for information (RFI), rather than the collection itself, which has caused some friction when working with U.S. collection assets. Within NATO, requests for information flowed through the chain of command to the CCIRM manager. Where the U.S. sees collection management as a "push" or proactive process, NATO sees this as "pull" or reactive.

In NATO doctrine, CCIRM joins an intelligence analysis (including fusion) to provide intelligence services to the force commander. Senior NATO commanders receive intelligence information in the form of briefings, summaries, reports and other intelligence estimates. According to authors Roberto Desimone and David Charles, "Battlefield commanders receive more specific documents, entitled intelligence preparation of the battlefield (IPB)." While these reports and briefings convey critical information, they lack the full context in which the intelligence cell assembled them. In coalition warfare, not all sources may be identified outside that cell. Even though the material presented gives key information and recommendations, and assumptions for these interpretations are given, the context "...not in a strong evidential sense, pointing exactly to the specific intelligence information that justifies these interpretations. As a result, it is not always easy for the commander to determine whether a particular interpretation has been compromised by new intelligence information, without constant interaction with the intelligence analysts. Conversely, security constraints may prevent the analyst from explaining exactly why a particular command decision might compromise existing intelligence gathering operations. As a result, most of the detailed intelligence analyses, including alternative hypotheses and interpretations, remain in the heads of intelligence officers who rely on individual communication skills to present their brief and keep the commander informed when the situation changes."[12]

Experience in Bosnia and Kosovo demonstrated strain between CCIRM and U.S. procedures, although the organizations learned by experience. Operation Joint Endeavor began in 1995, with Operation Deliberate Force going to a much higher level of combat. Operation Allied Force, a more intense combat situation in Kosovo, began on 24 March 1999.

At the highest level of direction, rational policies, the effects of personalities, and culture can dominate the assignments given to the intelligence services.

Another aspect of analysis is the balance between current intelligence and long-term estimates. For many years, the culture of the intelligence community, in particular that of the CIA, favored the estimates. However, it is in long-term analysis of familiar subjects and broad trends where secret information tends to be less critical and government analysts are, for the most part, no better and often not as good as their counterparts in academia and the private sector. Also, many estimates are likely to be less relevant to busy policy-makers, who must focus on the immediate. To the extent long-term estimates are produced, it is important that they be concise, written by individuals, and that sources justifying conclusions be shown as they would in any academic work. If the project is a group effort, differences among participants need to be sharpened and acknowledged. While it is valuable to point out consensus, it is more important that areas of dispute be highlighted than that all agencies be pressured to reach a conclusion that may represent a lowest common denominator.[8]

Issuance of orders and requests

Once the intelligence effort has been planned, it can then be directed, with orders and requests issued to intelligence collection agencies to provide specific types of intelligence inputs.

Prioritization

Upper managers may order the collection department to focus on specific targets and, on a longer-term basis (especially for the technical collection disciplines), may prioritize the means of collection through budgeting resources for one discipline versus another and, within a discipline, one system over another. Not only must collection be prioritized, but the analysts need to know where to begin in what is often a flood of information.

"Intelligence collection priorities, while reflecting both national interests and broader policy priorities, need to be based on other considerations. First, there must be a demonstrated inadequacy of alternative sources. Except in rare circumstances, the intelligence community does not need to confirm through intelligence what is already readily available." In most intelligence and operations watch centers, a television set is always tuned to the Cable News Network. While initial news reports may be fragmentary, this particular part of OSINT is a powerful component of warning, but not necessarily of detailed analyses.

"Collection priorities must not only be those subjects that are policy-relevant, but also involve information that the intelligence community can best (or uniquely) ascertain."[8]

Other topics

Political misuse

There has been a great amount of political abuse of intelligence services in totalitarian states, where the use of what the Soviets called the "organs of state security" would take on tasks far outside any intelligence mission.[13]

"The danger of politicization-the potential for the intelligence community to distort information or judgment in order to please political authorities-is real. Moreover, the danger can never be eliminated if intelligence analysts are involved, as they must be, in the policy process. The challenge is to develop reasonable safeguards while permitting intelligence producers and policy-making consumers to interact."[8]

Clandestine intelligence versus covert action

Clandestine and covert operations share many attributes, but also have distinct differences. They may share, for example, a technical capability for cover and forgery, and require secret logistical support. The essence of covert action is that its sponsor cannot be proven. One term of art is that the sponsor has "plausible deniability." In some cases, such as sabotage, the target indeed may not be aware of the action. Assassinations, however, are immediately known but, if the assassin escapes or is killed in action, the sponsor may never be known to any other than to the sponsor.

See a Congressional study, Special Operations Forces (SOF) and CIA Paramilitary Operations: Issues for Congress,[14] for one policy review.

Coordination of HUMINT and covert action

Experience has shown that high level government needs to be aware of both clandestine and covert field activities in order to prevent them from interfering with one another, and with secret activities that may not be in the field. For example, one World War II failure occurred when Office of Strategic Services (OSS) field agents broke into the Japanese Embassy in Lisbon, and stole cryptographic materials, which allowed past communications to be read. The net effect of this operation was disastrous, as the particular cryptosystem had been broken by cryptanalysis, who were reading the traffic parallel with the intended recipients. The covert burglary—the Japanese did not catch the OSS team, so were not certain who committed it—caused the Japanese to change cryptosystems, invalidating the clandestine work of the cryptanalysts.[15] In World War II, the United Kingdom kept its Secret Intelligence Service principally focused on HUMINT, while the Special Operations Executive was created for direct action and support of resistance movements. The Political Warfare Executive also was created, for psychological warfare.

HUMINT resources have been abused, even in democracies. In the case of the U.S., these abuses of resources involved instances such as Iran-Contra and support to the "plumbers unit" of the Nixon campaign and administration, as well as infiltrating legal groups using a justification of force protection. British actions in Northern Ireland, and against terror groups in Gibraltar and elsewhere, have been criticized, as have French actions against Greenpeace. "... Contrary to widespread impressions, one problem with the clandestine services has been a lack of initiative brought about by a fear of retroactive discipline and a lack of high-level support. This must be rectified if the intelligence community is to continue to produce the human intelligence that will surely be needed in the future."[8]

For a detailed discussion, see Clandestine HUMINT and Covert Action.

Common risks and resources

Clandestine collection entails many more risks than the technical collection disciplines. Therefore, how and when it is used must be highly selective, responding to carefully screened and the highest priority requirements. It cannot be kept "on the shelf" and called upon whenever needed. There must be some minimal ongoing capability that can be expanded in response to consumer needs. This has become increasingly difficult for clandestine services, such as diplomats, in response to budget pressures, and has reduced its presence that could otherwise provide official cover.

In 1996, the House Committee on Intelligence[16] recommended that a single clandestine service should include those components of the Defense HUMINT Service (DHS) that undertake clandestine collection, as well. The congressional concern about strategic military HUMINT, however, may not apply to military special operations forces or to force protection. "This is not meant to preclude the service intelligence chiefs from carrying out those clandestine collection activities specifically related to the tactical needs of their military departmental customers or field commanders."

Clandestine HUMINT and covert action involve the only part of governments that are required, on a routine basis, to break foreign laws. "As several former DCIs have pointed out, the clandestine services are also the DCI's most important 'action arm,' not only running covert action programs at the direction of the president (a function whose utility we believe will continue to be important), but also in managing most of the IC's liaison with foreign government leaders and security services. A House staff report is of the opinion that analysis should be separate from both covert action and clandestine HUMINT, or other clandestine collection that breaks foreign laws. HUMINT is and should be part of a larger IC-wide collection plan."[16]

Failures in the intelligence cycle

Any circular cycle is as weak as its weakest component. At one time or another, a national or organizational intelligence process has broken down, thus causing failure in the cycle. For example, failures in the intelligence cycle were identified in the 9/11 Commission Report.

Each of the five main components of the cycle has, in different countries and at different times, failed. Policy-makers have denied the services direction to work on critical matters. Intelligence services have failed to collect critical information. The services have analyzed data incorrectly. There have been failures to disseminate intelligence quickly enough, or to the right decision-makers. There have been failures to protect the intelligence process itself from opposing intelligence services.

A major problem, in several aspects of the enhanced cycle, is stovepiping or silos. In the traditional intelligence use of the term, stovepiping keeps the output of different collection systems separated from one another. This has several negative effects. For instance, it prevents one discipline from cross-checking another or from sharing relevant information.

Other cycles

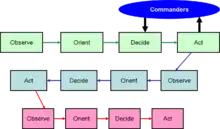

Boyd OODA loop

Military strategist John Boyd created a model of decision and action, originally for air-to-air fighter combat, but which has proven useful in many areas of conflict. His model has four phases, which, while not usually stated in terms of the intelligence cycle, do relate to that cycle:

- Observe: become aware of a threat or opportunity.

- Orient: put the observation into the context of other information.

- Decide: make the best possible action plan that can be carried out in a timely manner.

- Act: carry out the plan.

After the action, the actor observes again, to see the effects of the action. If the cycle works properly, the actor has initiative, and can orient, decide, and act even faster in the second and subsequent iterations of the Boyd loop.

Eventually, if the Boyd process works as intended, the actor will "get inside the opponent's loop". When the actor's Boyd cycle dominates the opponent's, the actor is acting repeatedly, based on reasoned choices, while the opponent is still trying to determine what is happening.

While Boyd treated his cycle as self-contained, it could be extended to meet the intelligence cycle. Observation could be an output of the collection phase, while orientation is an output of analysis.

Eventually, actions taken, and their results, affect the senior commanders. The guidelines for the preferred decisions and actions come from the commanders, rather than from the intelligence side.

References

- Sun Tzu (2019) [written in 6th Century BCE]. The Art of War. Translated by Lionel Giles. Amazon Kindle.

- Richelson, Jeffrey T. (2001). The Wizards of Langley: Inside the CIA's Directorate of Science and Technology. Westview Press. ISBN 978-0-8133-6699-9.

- Johnston, Rob (2005). "Analytic Culture in the US Intelligence Community: An Ethnographic Study". Center for the Study of Intelligence, Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on June 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- US Department of Defense (12 July 2007). "Joint Publication 1-02 Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 November 2008. Retrieved 2007-10-01.

- "Joint Publication 2-0, Joint Intelligence" (PDF). Defense Technical Information Center (DTIC). Department of Defense. 22 June 2007. pp. GL-11. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2016. Retrieved February 22, 2013.

- US Intelligence Board (2007). "Planning and Direction". Archived from the original on 2007-09-22. Retrieved 2007-10-22.

- Hulnick, Arthur S. (6 December 2006). "What's wrong with the Intelligence Cycle (abstract)". Intelligence & National Security. 21 (6): 959–979. doi:10.1080/02684520601046291. S2CID 145190138.

- Council on Foreign Relations. "Making Intelligence Smarter: The Future of US Intelligence". Retrieved 2007-10-21.

- Treverton, Gregory F. (July 2003). "Reshaping Intelligence to Share with "Ourselves"". Canadian Security Intelligence Service. Archived from the original on 2008-02-17. Retrieved 2007-10-23.

- (Treverton 2003)

- Wentz, Larry. "Lessons From Bosnia: The IFOR Experience, IV. Intelligence Operations". Archived from the original on 2007-10-20. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- Desimone, Roberto; David Charles. "Towards an Ontology for Intelligence Analysis and Collection Management" (PDF). Desimone 2003. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- Sudoplatov, Pavel; Anatoli Sudoplatov; Jerrold L. Schecter; Leona P. Schecter (1994). Special Tasks: The Memoirs of an Unwanted Witness—A Soviet Spymaster. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-316-77352-2.

- Congressional Research Service (December 6, 2006). "Special Operations Forces (SOF) and CIA Paramilitary Operations: Issues for Congress" (PDF).

- Kahn, David (1996). The Codebreakers - The Story of Secret Writing. Scribners. ISBN 978-0-684-83130-5.

- Staff Study, Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, House of Representatives, One Hundred Fourth Congress (1996). "IC21: The Intelligence Community in the 21st Century". Retrieved 2007-10-26.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)