Continuous positive airway pressure

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is a form of positive airway pressure (PAP) ventilation in which a constant level of pressure greater than atmospheric pressure is continuously applied to the upper respiratory tract of a person. The application of positive pressure may be intended to prevent upper airway collapse, as occurs in obstructive sleep apnea, or to reduce the work of breathing in conditions such as acute decompensated heart failure. CPAP therapy is highly effective for managing obstructive sleep apnea. Compliance and acceptance of use of CPAP therapy can be a limiting factor, with 8% of people stopping use after the first night and 50% within the first year.[1]

| Continuous positive airway pressure | |

|---|---|

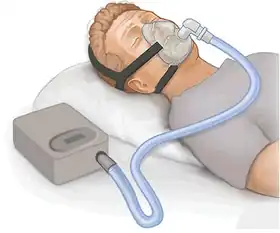

Equipment for CPAP therapy: flow generator, hose, full face mask |

Medical uses

Moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea

CPAP is the most effective treatment for moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea, in which the mild pressure from the CPAP prevents the airway from collapsing or becoming blocked.[1][2] CPAP has been shown to be 100% effective at eliminating obstructive sleep apneas in the majority of people who use the therapy according to the recommendations of their physician.[1] In addition, a meta-analysis showed that CPAP therapy may reduce erectile dysfunction symptoms in male patients with obstructive sleep apnea.[3]

Upper airway resistance syndrome

Upper airway resistance syndrome is another form of sleep-disordered breathing with symptoms that are similar to obstructive sleep apnea, but not severe enough to be considered OSA. CPAP can be used to treat UARS as the condition progresses, in order to prevent it from developing into obstructive sleep apnea.[4][5][6]

Pre-term infants

CPAP also may be used to treat pre-term infants whose lungs are not yet fully developed. For example, physicians may use CPAP in infants with respiratory distress syndrome. It is associated with a decrease in the incidence of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. In some preterm infants whose lungs have not fully developed, CPAP improves survival and decreases the need for steroid treatment for their lungs. In resource-limited settings where CPAP improves respiratory rate and survival in children with primary pulmonary disease, researchers have found that nurses can initiate and manage care with once- or twice-daily physician rounds.[7]

COVID-19

In March 2020, the USFDA suggested that CPAP devices may be used to support patients affected by COVID-19;[8] however, they recommended additional filtration since non-invasive ventilation may increase the risk of infectious transmission.[9]

Other uses

CPAP also has been suggested for treating acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure in children. However, due to a limited number of clinical studies, the effectiveness and safety of this approach to providing respiratory support is not clear.[10]

Contraindications

CPAP cannot be used in the following situations or conditions:[11]

- A person is not breathing on their own

- A person is uncooperative or anxious

- A person cannot protect their own airway (i.e., has altered consciousness for reasons other than sleep, such as extreme illness, intoxication, coma, etc.)

- A person is not stable due to respiratory arrest

- A person has experienced facial trauma or facial burns

- A person who has had previous facial, esophageal, or gastric surgery may find this a difficult or unsuitable treatment option, or may need to fully heal from surgery before using this treatment

Adverse effects

Some people experience difficulty adjusting to CPAP therapy and report general discomfort, nasal congestion, abdominal bloating, sensations of claustrophobia, mask leak problems, and convenience-related complaints.[1] Oral leak problems also interfere with CPAP effectiveness.[12]

Mechanism

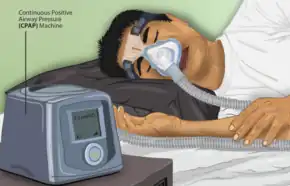

CPAP therapy uses machines specifically designed to deliver a flow of air at a constant pressure. CPAP machines possess a motor that pressurizes room temperature air and delivers it through a hose connected to a mask or tube worn by the patient. This constant stream of air opens and keeps the upper airway unobstructed during inhalation and exhalation.[1] Some CPAP machines have other features as well, such as heated humidifiers.

The therapy is an alternative to positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Both modalities stent open the alveoli in the lungs and thus recruit more of the lung surface area for ventilation. However, while PEEP refers to devices that impose positive pressure only at the end of the exhalation, CPAP devices apply continuous positive airway pressure throughout the breathing cycle. Thus, the ventilator does not cycle during CPAP, no additional pressure greater than the level of CPAP is provided, and patients must initiate all of their breaths.[13]

Nasal CPAP

Nasal prongs or a nasal mask is the most common modality of treatment.[11] Nasal prongs are placed directly in the person's nostrils. A nasal mask is a small mask that covers the nose. There are also nasal pillow masks which have a cushion at the base of the nostrils, and are considered the least invasive option.[14] Frequently, nasal CPAP is used for infants, although this use is controversial. Studies have shown nasal CPAP reduces ventilator time, but an increased occurrence of pneumothorax also was prevalent.[15]

Nasopharyngeal CPAP

Nasopharyngeal CPAP is administered by a tube that is placed through the person's nose and ends in the nasopharynx.[11] This tube bypasses the nasal cavity in order to deliver the CPAP farther down in the upper respiratory system.

Face mask

A full face mask over the mouth and nose is another approach for people who breathe out of their mouths when they sleep.[11] Often, oral masks and naso-oral masks are used when nasal congestion or obstruction is an issue. There are also devices that combine nasal pressure with mandibular advancement devices (MAD).

Compliance

A large portion of people do not adhere to the recommended method of CPAP therapy, with more than 50% of people discontinuing use in the first year.[1] A significant change in behaviour is required in order to commit to long-term use of CPAP therapy and this can be difficult for many people,[1] since CPAP equipment must be used consistently for all sleep (including naps and overnight trips away from home) and needs to be regularly maintained and replaced over time. In addition, people with moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea have a higher risk of concomitant symptoms such as anxiety and depression, which can make it more difficult to change their sleep habits and to use CPAP on a regular basis.[1] Educational and supportive approaches have been shown to help motivate people who need CPAP therapy to use their devices more often.[1]

History

Colin Sullivan, an Australian physician and professor, invented CPAP in 1980 at Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney.[16]

See also

- Positive end-expiratory pressure – pressure in the lungs above atmospheric pressure that exists at the end of expiration

References

- Askland, Kathleen; Wright, Lauren; Wozniak, Dariusz R.; Emmanuel, Talia; Caston, Jessica; Smith, Ian (April 2020). "Educational, supportive and behavioural interventions to improve usage of continuous positive airway pressure machines in adults with obstructive sleep apnoea". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (4): CD007736. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd007736.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 7137251. PMID 32255210.

- Werman, Howard A.; Karren, K; Mistovich, Joseph (2014). "Continuous Positive Airway Pressure(CPAP)". In Werman A. Howard; Mistovich J; Karren K (eds.). Prehospital Emergency Care, 10e. Pearson Education, Inc. p. 242.

- Yang, Zhihao; Du, Guodong; Ma, Lei; Lv, Yunhui; Zhao, Yang; Yau, Tung On (February 2021). "Continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnoea patients with erectile dysfunction-A meta-analysis". The Clinical Respiratory Journal. 15 (2): 163–168. doi:10.1111/crj.13280. ISSN 1752-699X. PMID 32975905. S2CID 221917475.

- de Godoy, Luciana B.M.; Palombini, Luciana O.; Guilleminault, Christian; Poyares, Dalva; Tufik, Sergio; Togeiro, Sonia M. (January 2015). "Treatment of upper airway resistance syndrome in adults: Where do we stand?". Sleep Science. 8 (1): 42–48. doi:10.1016/j.slsci.2015.03.001. ISSN 1984-0063. PMC 4608900. PMID 26483942.

- "Treatments". stanfordhealthcare.org. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- Repasky, David (2021-03-03). "CPAP Machine: How It Works, Reasons, and Uses". CPAP.com. Archived from the original on 2020-09-27. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- Patrick, Wilson; Moresky, Rachel; Baiden, Frank; Brooks, Joshua; Morris, Marilyn; Giessler, Katie; Punguyire, Damien; Apio, Gavin; Agyeman-Ampromfi, Akua; Lopez-Pintado, Sara; Sylverken, Justice; Nyarko-Jectey, Kwadwo; Tagbor, Harry (June 2017). "Continuous positive airway pressure for children with undifferentiated respiratory distress in Ghana: an open-label, cluster, crossover trial". Lancet Global Health. 5 (6): e615–e623. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30145-6. PMID 28495265.

- "Ventilator Supply Mitigation Strategies: Letter to Health Care Providers". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- "COVID-19 resources for anesthesiologists". asahq.org. American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA). Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Shah, Prakeshkumar S.; Ohlsson, Arne; Shah, Jyotsna P. (2013-11-04). "Continuous negative extrathoracic pressure or continuous positive airway pressure compared to conventional ventilation for acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure in children". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 (11): CD003699. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003699.pub4. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 6464907. PMID 24186774.

- Pinto, Venessa L.; Sharma, Sandeep (2020), "Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP)", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29489216, retrieved 2020-09-02

- Genta, Pedro R.; Lorenzi-Filho, Geraldo (April 2018). "Sealing the Leak". Chest. 153 (4): 774–775. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2017.10.023.

- Werman, Howard A.; Karren, K; Mistovich, Joseph (2014). "Continuous Positive Airway Pressure(CPAP)". In Werman A. Howard; Mistovich J; Karren K (eds.). Prehospital Emergency Care, 10e. Pearson Education, Inc.

- "Slide show: Which CPAP masks are best for you?". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2021-05-11.

- Morley, C. J.; Davis, P. G.; Doyle, L. W.; Brion, L. P.; Hascoet, J. M.; Carlin, J. B.; Coin Trial, I. (2008). "Nasal CPAP or Intubation at Birth for Very Preterm Infants" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 358 (7): 700–708. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa072788. PMID 18272893.

- "CPAP: Resources, Sleep Apnea Machines, & Masks". 29 June 2009.

External links

- Winters, Catherine (December 25, 2016). "How to Stop Snoring". Consumer Reports. Retrieved December 20, 2019.