Snorkel (swimming)

A snorkel is a device used for breathing air from above the surface when the wearer's head is face downwards in the water with the mouth and the nose submerged. It may be either separate or integrated into a swimming or diving mask. The integrated version is only suitable for surface snorkeling, while the separate device may also be used for underwater activities such as spearfishing, freediving, finswimming, underwater hockey, underwater rugby and for surface breathing with scuba equipment. A swimmer's snorkel is a tube bent into a shape often resembling the letter "L" or "J", fitted with a mouthpiece at the lower end and constructed of light metal, rubber or plastic. The snorkel may come with a rubber loop or a plastic clip enabling the snorkel to be attached to the outside of the head strap of the diving mask. Although the snorkel may also be secured by tucking the tube between the mask-strap and the head, this alternative strategy can lead to physical discomfort, mask leakage or even snorkel loss.[1]

Snorkel, worn with diving half mask | |

| Uses | Breathing while face down at the surface of the water |

|---|---|

| Related items | Diving mask, Swimming goggles |

To comply with the current European standard EN 1972 (2015), a snorkel for users with larger lung capacities should not exceed 38 centimeters (15") in length and 230 cubic centimeters (14 cu. in.) in internal volume, while the corresponding figures for users with smaller lung capacities are 35 cm (14") and 150 cc (9¼ cu. in.) respectively.[2] Current World Underwater Federation (CMAS) Surface Finswimming Rules (2017) require snorkels used in official competitions to have a total length between 43 and 48 cm (17" and 19") and to have an inner diameter between 1.5 and 2.3 cm (½" and 1").[3] A longer tube would not allow breathing when snorkeling deeper, since it would place the lungs in deeper water where the surrounding water pressure is higher. The lungs would then be unable to inflate when the snorkeler inhales, because the muscles that expand the lungs are not strong enough to operate against the higher pressure.[4] The pressure difference across the tissues in the lungs, between the blood capillaries and air spaces would increase the risk of pulmonary edema.

Snorkels constitute respiratory dead space. When the user takes in a fresh breath, some of the previously exhaled air which remains in the snorkel is inhaled again, reducing the amount of fresh air in the inhaled volume, and increasing the risk of a buildup of carbon dioxide in the blood, which can result in hypercapnia. The greater the volume of the tube, and the smaller the tidal volume of breathing, the more this problem is exacerbated. Including the internal volume of the mask in the breathing circuit greatly expands the dead space. Occasional exhalation through the nose while snorkeling with a separate snorkel will slightly reduce the buildup of carbon dioxide, and may help in keeping the mask clear of water, but in cold water it will increase fogging. To some extent the effect of dead space can be counteracted by breathing more deeply and slowly, as this reduces the dead space ratio and work of breathing.

Operation

The simplest type of snorkel is a plain tube that is held in the mouth, and allowed to flood when underwater. The snorkeler expels water from the snorkel either with a sharp exhalation on return to the surface (blast clearing) or by tilting the head back shortly before reaching the surface and exhaling until reaching or breaking the surface (displacement method) and facing forward or down again before inhaling the next breath. The displacement method expels water by filling the snorkel with air; it is a technique that takes practice but clears the snorkel with less effort, but only works when surfacing. Clearing splash water while at the surface requires blast clearing.[5]

Single snorkels and two-way twin snorkels constitute respiratory dead space. When the user takes in a fresh breath, some of the previously exhaled air which remains in the snorkel is inhaled again, reducing the amount of fresh air in the inhaled volume, and increasing the risk of a buildup of carbon dioxide in the blood, which can result in hypercapnia. The greater the volume of the tube, and the smaller the tidal volume of breathing, the more this problem is exacerbated. Including the internal volume of the mask in the breathing circuit greatly expands the dead space. A smaller diameter tube reduces the dead volume, but also increases resistance to airflow and so increases the work of breathing. Occasional exhalation through the nose while snorkeling with a separate snorkel will slightly reduce the buildup of carbon dioxide, and may help in keeping the mask clear of water, but in cold water it will increase fogging. Twin integrated snorkels with one-way valves eliminate the dead-space of the snorkels themselves, but are usually used on a full-face mask, and even if it has an inner oro-nasal section, there will be some dead space, and the valves will impede airflow through the loop. Integrated two-way snorkels include the internal volume of the mask as dead space in addition to the volume of the snorkels. To some extent the effect of dead space can be counteracted by breathing more deeply, as this reduces the dead space ratio. Slower breathing will reduce the effort needed to move the air through the circuit. There is a danger that a snorkeler who can breathe comfortably in good conditions will be unable to ventilate adequately under stress or when working harder, leading to hypercapnia and possible panic, and could get into serious difficulties if they are unable to swim effectively if they have to remove the snorkel or mask to breathe without restriction.

Some snorkels have a sump at the lowest point to allow a small volume of water to remain in the snorkel without being inhaled when the snorkeler breathes. Some also have a non-return valve in the sump, to drain water in the tube when the diver exhales. The water is pushed out through the valve when the tube is blocked by water and the exhalation pressure exceeds the water pressure on the outside of the valve. This is almost exactly the mechanism of blast clearing which does not require the valve, but the pressure required is marginally less, and effective blast clearing requires a higher flow rate. The full face mask has a double airflow valve which allows breathing through the nose in addition to the mouth.[6] A few models of snorkel have float-operated valves attached to the top end of the tube to keep water out when a wave passes, but these cause problems when diving as the snorkel must then be equalized during descent, using part of the diver's inhaled air supply. Some recent designs have a splash deflector on the top end that reduces entry of any water that splashes over the top end of the tube, thereby keeping it relatively free from water.[7]

Finswimmers do not normally use snorkels with a sump valve, as they learn to blast clear the tube on most if not all exhalations, which keeps the water content in the tube to a minimum as the tube can be shaped for lower work of breathing, and elimination of water traps, allowing greater speed and lowering the stress of eventual swallowing of small quantities of water, which would impede their competition performance.[8]

A common problem with all mechanical clearing mechanisms is their tendency to fail if infrequently used, or if stored for long periods, or through environmental fouling, or owing to lack of maintenance. Many also either slightly increase the flow resistance of the snorkel, or provide a small water trap, which retains a little water in the tube after clearing.[9]

Modern designs use silicone rubber in the mouthpiece and valves due to its resistance to degradation and its long service life. Natural rubber was formerly used, but slowly oxidizes and breaks down due to ultraviolet light exposure from the sun. It eventually loses its flexibility, becomes brittle and cracks, which can cause clearing valves to stick in the open or closed position, and float valves to leak due to a failure of the valve seat to seal. In even older designs, some snorkels were made with small "ping pong" balls in a cage mounted to the open end of the tube to prevent water ingress. These are no longer sold or recommended because they are unreliable and considered hazardous. Similarly, diving masks with a built-in snorkel are considered unsafe by scuba diving organizations such as PADI and BSAC because they can engender a false sense of security and can be difficult to clear if flooded.

Experienced users tend to develop a surface breathing style which minimises work of breathing, carbon dioxide buildup and risk of water inspiration, while optimising water removal. This involves a sharp puff in the early stage of exhalation, which is effective for clearing the tube of remaining water, and a fairly large but comfortable exhaled volume, mostly fairly slowly for low work of breathing, followed by an immediate slow inhalation, which reduces entrainment of any residual water, to a comfortable but relatively large inhaled volume, repeated without delay. Elastic recoil is used to assist with the initial puff, which can be made sharper by controlling the start of exhalation with the tongue. This technique is most applicable to relaxed cruising on the surface. Racing finswimmers may use a different technique as they need a far greater level of ventilation when working hard.

Scuba diving

A snorkel can be useful when scuba diving as it is a safe way of swimming face down at the surface for extended periods to conserve the bottled air supply, or in an emergency situation when there is a problem with either air supply or regulator.[10] Many dives do not require the use of a snorkel at all, and some scuba divers do not consider a snorkel a necessary or even useful piece of equipment, but the usefulness of a snorkel depends on the dive plan and the dive site. If there is no requirement to swim face down and see what is happening underwater, then a snorkel is not useful. If it is necessary to swim over heavy seaweed which can entangle the pillar valve and regulator if the diver swims face upward to get to and from the dive site, then a snorkel is useful to save breathing gas.

History

Snorkeling is mentioned by Aristotle in his Parts of Animals. He refers to divers using "instruments for respiration" resembling the elephant's trunk.[11] Some evidence suggests that snorkeling may have originated in Crete some 5,000 years ago as sea sponge farmers used hollowed out reeds to submerge and retrieve natural sponge for use in trade and commerce. In the fifteenth century, Leonardo da Vinci drew designs for an underwater breathing device consisting of cane tubes with a mask to cover the mouth at the demand end and a float to keep the tubes above water at the supply end.[12][13] The following timeline traces the history of the swimmers' snorkel during the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

1927: First use of swimmer's breathing tube and mask. According to Dr Gilbert Doukan's 1957 World Beneath the Waves[14] and cited elsewhere,[15] "In 1927, and during each summer from 1927 to 1930, on the beach of La Croix-Valmer, Jacques O'Marchal (Sic. "Jacques Aumaréchal" is the name of a 1932 French swim mask patentee[16]) could be seen using the first face mask and the first breathing tube. He exhibited them, in fact, in 1931, at the International Nautical Show. On his feet, moreover, he wore the first 'flippers' designed by Captain de Corlieu, the use of which was to become universal."

1929: First swimmers' breathing tube patent application filed. On 9 December 1929, Barney B. Girden files a patent application for a "swimming device" enabling a swimmer under instruction to be supplied with air through a tube to the mouth "whereby the wearer may devote his entire time to the mechanics of the stroke being used." His invention earns US patent 1,845,263 on 16 February 1932.[17] On 30 July 1932, Joseph L. Belcher files a patent application for "breathing apparatus" delivering air to a submerged person by suction from the surface of the water through hoses connected to a float; US patent 1,901,219 is awarded on 14 March 1933.[18]

1938: First swimmers' mask with integrated breathing tubes. In 1938, French naval officer Yves Le Prieur introduces his "Nautilus" full-face diving mask with hoses emerging from the sides and leading upwards to an air inlet device whose ball valve opens when it is above water and closes when it is submerged.[19][20][21] In November 1940, American spearfisherman Charles H. Wilen files his "swimmer's mask" invention, which is granted US patent 2,317,237 of 20 April 1943.[22] The device resembles a full-face diving mask incorporating two breathing tubes topped with valves projecting above the surface for inhalation and exhalation purposes. On 11 July 1944, he obtains US design patent 138,286 for a simpler version of this mask with a flutter valve at the bottom and a single breathing tube with a ball valve at the top.[23] Throughout their heydey of the 1950s and early 1960s, masks with integrated tubes appear in the inventories of American, Australian, British, Danish, French, German, Greek, Hong Kong, Israeli, Italian, Japanese, Polish, Spanish, Taiwanese, Turkish and Yugoslav swimming and diving equipment manufacturers. Meanwhile, in 1957, the US monthly product-testing magazine Consumer Reports concludes that "snorkel-masks have some value for swimmers lying on the surface while watching the depths in water free of vegetation and other similar hazards, but they are not recommended for a dive 'into the blue'".[24] According to an underwater swimming equipment review in the British national weekly newspaper The Sunday Times in December 1973, "the mask with inbuilt snorkel is doubly dangerous (...) A ban on the manufacture and import of these masks is long overdue in Britain".[25] In a decree of 2 August 1989,[26] the French government suspends the manufacture, importation and marketing of ball-valve snorkel-masks. By the noughties, just two swim masks with attached breathing tubes remain in production worldwide: the Majorca sub 107S single-snorkel model[27] and the Balco 558 twin-snorkel full-face model,[28] both manufactured in Greece. In May 2014, the French Decathlon company files its new-generation full-face snorkel-mask design, which is granted US design patent 775,722[29] on 3 January 2017, entering production as the "Easybreath" mask designated for surface snorkeling only.

1938: First front-mounted swimmer's breathing tube patent filed. In December 1938, French spearfisherman Maxime Forjot and his business partner Albert Méjean file a patent application in France for a breathing tube worn on the front of the head over a single-lens diving mask enclosing the eyes and the nose and it is granted French patent 847848 on 10 July 1939.[30][31][32][33] In July 1939, Popular Science magazine publishes an article containing illustrations of a spearfisherman using a curved length of hosepipe as a front-mounted breathing tube and wearing a set of swimming goggles over his eyes and a pair of swimming fins on his feet.[34] In the first French monograph on spearfishing La Chasse aux Poissons (1940), medical researcher and amateur spearfisherman Dr Raymond Pulvénis illustrates his "Tuba", a breathing tube he designed to be worn on the front of the head over a single-lens diving mask enclosing the eyes and the nose. Francophone swimmers and divers have called their breathing tube "un tuba" ever since. In 1943, Raymond Pulvénis and his brother Roger obtain a Spanish patent for their improved breathing tube mouthpiece design.[35] In 1956, the UK diving equipment manufacturer E. T. Skinner (Typhoon) markets a "frontal" breathing tube with a bracket attachable to the screw at the top of an oval diving mask.[36] Although it falls out of favour with underwater swimmers eventually, the front-mounted snorkel becomes the breathing tube of choice in competitive swimming and finswimming because it contributes to the swimmer's hydrodynamic profile.

1939: First side-mounted swimmers’ breathing tube patent filed. In December 1939, expatriate Russian spearfisherman Alexandre Kramarenko files a patent in France for a breathing tube worn at the side of the head with a ball valve at the top to exclude water and a flutter valve at the bottom. Kramarenko and his business partner Charles H. Wilen refile the invention in March 1940 with the United States Patent Office, where their "underwater apparatus for swimmers" is granted US patent 2,317,236 on 20 April 1943;[37] after entering production in France, the device is called "Le Respirator".[38] The co-founder of Scubapro Dick Bonin is credited with the introduction of the flexible-hose snorkel in the mid-1950s and the exhaust valve to ease snorkel clearing in 1980.[39] In 1964, US Divers markets an L-shaped snorkel designed to outperform J-shaped models by increasing breathing ease, cutting water drag and eliminating the "water trap".[40] In the late 1960s, Dacor launched a "wraparound big-barrel" contoured snorkel, which closely follows the outline of the wearer's head and comes with a wider bore to improve airflow.[41] The findings of the 1977 report "Allergic reactions to mask skirts, regulator mouthpieces and snorkel mouthpieces"[42] encourage diving equipment manufacturers to fit snorkels with hypoallergenic gum rubber and medical-grade silicone mouthpieces. In the world of underwater swimming and diving, the side-mounted snorkel has long become the norm, although new-generation full-face swim masks with integrated snorkels are beginning to grow in popularity for use in floating and swimming on the surface.

1950: First use of "snorkel" to denote a breathing device for swimmers. In November 1950, the Honolulu Sporting Goods Co. introduces a "swim-pipe" resembling Kramarenko and Wilen's side-mounted ball- and flutter-valve breathing tube design, urging children and adults to "try the human version of the submarine snorkel and be like a fish".[43] Every advertisement in the first issue of Skin Diver magazine in December 1951[44] uses the alternative spelling "snorkles" to denote swimmers’ breathing tubes. In 1955, Albert VanderKogel classes stand-alone breathing tubes and swim masks with integrated breathing tubes as "pipe snorkels" and "mask snorkels" respectively.[45] In 1957, the British Sub-Aqua Club journal features a lively debate about the standardisation of diving terms in general and the replacement of the existing British term "breathing tube" with the American term "snorkel" in particular.[46] The following year sees the première of the 1958 British thriller film The Snorkel, whose title references a diving mask topped with two built-in breathing tubes. To date, every national and international standard on snorkels uses the term "snorkel" exclusively. The German word Schnorchel originally referred to an air intake used to supply air to the diesel engines of U-boats, invented during World War II to allow them to operate just below the surface at periscope depth, and recharge batteries while keeping a low profile. First recorded in 1940–45.[47]

1969: First national standard on snorkels. In December 1969, the British Standards Institution publishes British standard BS 4532 entitled "Specification for snorkels and face masks"[48] and prepared by a committee on which the British Rubber Manufacturers' Association, the British Sub-Aqua Club, the Department for Education and Science, the Federation of British Manufacturers of Sports and Games, the Ministry of Defence Navy Department and the Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents are represented. This British standard sets different maximum and minimum snorkel dimensions for adult and child users, specifies materials and design features for tubes and mouthpieces and requires a warning label and a set of instructions to be enclosed with each snorkel. In February 1980 and June 1991, the Deutsches Institut für Normung publishes the first[49] and second[50] editions of German standard DIN 7878 on snorkel safety and testing. This German standard sets safety and testing criteria comparable to British standard BS 4532 with an additional requirement that every snorkel must be topped with a fluorescent red or orange band to alert other water users of the snorkeller's presence. In November 1988, Austrian Standards International publishes Austrian standard ÖNORM S 4223[51] entitled "Tauch-Zubehör; Schnorchel; Abmessungen, sicherheitstechnische Anforderungen, Prüfung, Normkennzeichnung" in German, subtitled "Diving accessories; snorkel; dimensions, safety requirements, testing, marking of conformity" in English and closely resembling German Standard DIN 7878 of February 1980 in specifications. The first[52] and second[2] editions of European standard EN 1972 on snorkel requirements and test methods appear in July 1997 and December 2015. This European standard refines snorkel dimension, airflow and joint-strength testing and matches snorkel measurements to the user's height and lung capacity. The snorkels regulated by these British, German, Austrian and European standards exclude combined masks and snorkels in which the snorkel tubes open into the mask.

Separate snorkels

A snorkel may be either separate from, or integrated into, a swim or dive mask. The integrated snorkel mask may be a half-mask, which encloses the eyes and nose but excludes the mouth, or a full-face mask, which covers the eyes, nose, and mouth.

A separate snorkel typically comprises a tube for breathing and a means of attaching the tube to the head of the wearer. The tube has an opening at the top and a mouthpiece at the bottom. Some tubes are topped with a valve to prevent water from entering the tube when it is submerged.

Although snorkels come in many forms, they are primarily classified by their dimensions and secondarily by their orientation and shape. The length and the inner diameter (or inner volume) of the tube are paramount health and safety considerations when matching a snorkel to the morphology of its end-user. The orientation and shape of the tube must also be taken into account when matching a snorkel to its use while seeking to optimise ergonomic factors such as streamlining, airflow and water retention.

Dimensions

The total length, inner diameter and internal volume of a snorkel tube are matters of utmost importance because they affect the user's ability to breathe normally while swimming or floating head downwards on the surface of the water. These dimensions also have implications for the user's ability to blow residual water out of the tube when surfacing. A long or narrow snorkel tube, or a tube with abrupt changes in direction, or internal surface irregularities will have greater breathing resistance, while a wide tube will have a larger dead space and may be hard to clear of water. A short tube will be susceptible to swamping by waves.

To date, all national and international standards on snorkels specify two ranges of tube dimensions to meet the health and safety needs of their end-users, whether young or old, short or tall, with low or high lung capacity. The snorkel dimensions at issue are the total length, the inner diameter and/or the inner volume of the tube. The specifications of the standardisation bodies are tabulated below.

| Snorkel standards and rules | Total length | Inner diameter | Total inner volume |

|---|---|---|---|

| British Standard: BS 4532 (1969) | 500 mm – 600 mm | 15 mm – 18 mm | |

| British Standard: BS 4532 (1977) | 300 mm – 600 mm | 15 mm – 22.5 mm. An inner diameter exceeding 20 mm is child-inappropriate. | |

| German Standard: DIN 7878 (1980) | Form A (Children): 300 mm max. Form B (Adults): 350 mm max. | Form A (Children): 15 mm – 18 mm. Form B (Adults): 18 mm – 25 mm. | Form A (Children): 120 cc max. Form B (Adults): 150 cc max. |

| Austrian Standard: ÖNORM S 4223 (1988) | Form A (Children): 300 mm max. Form B (Adults): 350 mm max. | Form A (Children): 15 mm – 18 mm. Form B (Adults): 18 mm – 25 mm. | Form A (Children): 120 cc max. Form B (Adults): 150 cc max. |

| German Standard: DIN 7878 (1991) | Form A (Users over ten years of age): 350 mm max. Form C (Ten-year-olds and younger): 300 mm max. | Form A (Users over ten years of age): 18 mm min. Form C (Ten-year-olds and younger): 18 mm min. | Form A (Users over ten years of age): 180 cc max. Form C (Ten-year-olds and younger): 120 cc max. |

| European Standard: EN 1972 (1997) | Type 1 (Users 150 cm or less in height): 350 mm max. Type 2 (Users exceeding 150 cm in height): 380 mm max. Competitive finswimming: 480 mm max. | Type 1 (Users 150 cm or less in height): 150 cc max. Type 2 (Users exceeding 150 cm in height): 230 cc max. Competitive finswimming: 230 cc max. | |

| European Standard: EN 1972 (2015) | Class A (Users with larger lung capacity): 380 mm max. Class B (Users with smaller lung capacity, e.g. children): 350 mm max. | Class A (Users with larger lung capacity): 230 cc max. Class B (Users with smaller lung capacity, e.g. children): 150 cc max. | |

| World Underwater Federation (CMAS) Surface Finswimming Rules (2017) | 430 mm – 480 mm. | 15 mm – 23 mm. Tube cross-section to be circular. |

The table above shows how snorkel dimensions have changed over time in response to progress in swimming and diving science and technology:

- Maximum tube length has almost halved (from 600 to 380 mm).

- Maximum bore (inner diameter) has increased (from 18 to 25 mm).

- Capacity (or inner volume) has partly replaced inner diameter when dimensioning snorkels.

- Different snorkel dimensions have evolved for different users (first adults/children; then taller/shorter heights; then larger/smaller lung capacities).

Orientation and shape

Snorkels come in two orientations: Front-mounted and side-mounted. The first snorkel to be patented in 1938 was front-mounted, worn with the tube over the front of the face and secured with a bracket to the diving mask. Front-mounted snorkels proved popular in European snorkeling until the late 1950s, when side-mounted snorkels came into the ascendancy. Front-mounted snorkels experienced a comeback a decade later as a piece of competitive swimming equipment to be used in pool workouts and in finswimming races, where they outperform side-mounted snorkels in streamlining. Front-mounted snorkels are attached to the head with a special head bracket fitted with straps to be adjusted and buckled around the temples.

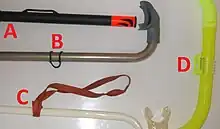

Side-mounted snorkels are generally worn by scuba divers on the left-hand side of the head because the scuba regulator is placed over the right shoulder. They come in at least four basic shapes: J-shaped; L-shaped; Flexible-hose; Contour.[53]

- A. J-shaped snorkels represent the original side-mounted snorkel design, cherished by some for their simplicity but eschewed by others because water accumulates in the U-bend at the bottom.

- B. L-shaped snorkels represent an improvement on the J-shaped style. They claim to reduce breathing resistance, to cut water drag and to remove the "water trap".

- C. Flexible-hose snorkels curry favour with some scuba divers because the flexible hose between the tube and the mouthpiece causes the lower part of the snorkel to drop out of the way when it is no longer in use. However, a spearfisher equipped with this snorkel must have a hand free to replace the mouthpiece when it falls out of the mouth.

- D. Contour snorkels represent the most recent design. They have a "wraparound" shape with smooth curves closely following the outline of the wearer's head, which improves wearing comfort.

Construction

A snorkel consists essentially of a tube with a mouthpiece to be inserted between the lips.

The barrel is the hollow tube leading from the supply end at the top of the snorkel to the demand end at the bottom where the mouthpiece is attached. The barrel is made of a relatively rigid material such as plastic, light metal or hard rubber. The bore is the interior chamber of the barrel; bore length, diameter and curvature all affect breathing resistance.

The top of the barrel may be open to the elements or fitted with a valve designed to shut off the air supply from the atmosphere when the top is submerged. There may be a fluorescent red or orange band around the top to alert other water users of the snorkeller's presence. The simplest way of attaching the snorkel to the head is to slip the top of the barrel between the mask strap and the head. This may cause the mask to leak, however, and alternative means of attachment of the barrel to the head can be seen in the illustration of connection methods.

- A. The mask strap is threaded through the permanent plastic loop moulded on to the centre of the barrel.

- B. The mask strap is threaded through the separable rubber loop pulled down to the centre of the barrel.

- C. The rubber band knotted to the centre of the barrel is stretched over the temple. This method was last used in the USA during the 1950s.

- D. The mask strap is threaded through the rotatable plastic snorkel keeper positioned at the centre of the barrel.

Attached to the demand end of the snorkel at the bottom of the barrel, the mouthpiece serves to keep the snorkel in the mouth. It is made of soft and flexible material, typically natural rubber and latterly silicone or PVC. The commonest of the multiple designs available[54] features a slightly concave flange with two lugs to be gripped between the teeth:

- A. Flanged mouthpiece with twin lugs at end of length of flexible corrugated hose designed for flexible-hose snorkel.

- B. Flanged mouthpiece with twin lugs at the end of short neck designed for J-shaped snorkel.

- C. Flanged mouthpiece with twin lugs positioned at a right angle and designed for an L-shaped snorkel.

- D. Flanged mouthpiece with twin lugs at the end of a flexible U-shaped elbow designed to be combined with a straight barrel to create a J-shaped snorkel.

- E. Flanged mouthpiece with twin bite plates offset at an angle from a contoured snorkel.

A disadvantage of mouthpieces with lugs is the presence of the teeth when breathing. The tighter the teeth grip the mouthpiece lugs, the smaller the air gap between the teeth and the harder it will be to breathe.

Snorkel design is only limited by the imagination. Among recent innovations is the "collapsible snorkel", which can be folded up in a pocket for emergencies.[55] One for competitive swimmers is a lightweight lap snorkel with twin tubes;[56] another is a "restrictor cap" placed inside a snorkel barrel "restricting breathing by 40% to increase cardiovascular strength and build lung capacity".[57] Some additional snorkel features such as shut-off and drain valves fell out of favour decades ago, only to return in the contemporary era as more reliable devices for incorporation into "dry" and "semi-dry" snorkels.[7]

Diving mask

Snorkelers normally wear the same kind of mask as those worn by scuba divers and freedivers when using a separate snorkel. By creating an airspace in front of the cornea, the mask enables the snorkeler to see clearly underwater. Scuba- and freediving masks consist of flat lenses also known as a faceplate, a soft rubber skirt, which encloses the nose and seals against the face, and a head strap to hold the mask in place. There are different styles and shapes, which range from oval shaped models to lower internal volume masks and may be made from different materials; common choices are silicone and rubber. A snorkeler who remains at the surface can use swimmer's goggles which do not enclose the nose, as there is no need to equalise the internal pressure.

Integrated snorkels

In this section, usage of the term "snorkel" denotes single or multiple tubular devices integrated with, and opening into, a swim or dive mask, while the term "snorkel-mask" is used to designate a swim or dive mask with single or multiple built-in snorkels. Such snorkels from the past typically comprised a tube for breathing and a means of connecting the tube to the space inside the snorkel-mask. The tube had an aperture with a shut-off valve at the top and opened at the bottom into the mask, which might cover the mouth as well as the nose and eyes. Although such snorkels tended to be permanent fixtures on historical snorkel-masks, a minority could be detached from their sockets and replaced with plugs enabling certain snorkel-masks to be used without their snorkels.

The 1950s were the heyday of older-generation snorkel-masks, first for the pioneers of underwater hunting and then for the general public who swam in their wake. One even-minded authority of the time declared that "the advantage of this kind of mask is mainly from the comfort point of view. It fits snugly to one's face, there is no mouthpiece to bite on, and one can breathe through either nose or mouth".[58] Another concluded with absolute conviction that "built-in snorkel masks are the best" and "a must for those who have sinus trouble."[59] Yet others, including a co-founder of the British Sub-Aqua Club, deemed masks with integrated snorkels to be complicated and unreliable: "Many have the breathing tube built in as an integral part of the mask. I have never seen the advantage of this, and this is the opinion shared by most experienced underwater swimmers I know".[60] Six decades on, a new generation of snorkel-masks has come to the marketplace.

Like separate snorkels, integrated snorkels come in a variety of forms. The assortment of older-generation masks with integrated snorkels highlights certain similarities and differences:

- A. A model enclosing the eyes and the nose only. A permanent single snorkel emerges from the top of the mask and terminates above with a shut-off ball valve.

- B. A model with a chinpiece to enclose the eyes, the nose and the mouth. Permanent twin snorkels emerge from either side of the mask and terminate above with shut-off "gamma" valves.

- C. A model enclosing the eyes and the nose only. Removable twin snorkels emerge from either side of the mask and terminate above with shut-off ball valves. Supplied with plugs for use without snorkels, as illustrated.

Integrated snorkels are tentatively classified here by their tube configuration and by the face coverage of the masks to which they are attached.

Tube configuration

As a rule, early manufacturers and retailers classed integrated snorkel masks by the number of breathing tubes projecting from their tops and sides. Their terse product descriptions often read: "single snorkel mask", "twin snorkel mask", "double snorkel mask" or "dual snorkel mask".[61]

Construction

An integrated snorkel consists essentially of a tube topped with a shut-off valve and opening at the bottom into the interior of a diving mask.

Tubes are made of strong but lightweight materials such as plastic. At the supply end, they are fitted with valves made of plastic, rubber or latterly silicone. Three typical shut-off valves are illustrated.

- A. Ball valve using a ping-pong ball in a cage to prevent water ingress when submerged. This device may be the most common and familiar valve used atop old-generation snorkels, whether separate or integrated.

- B. Hinged "gamma" valve to prevent water ingress when submerged. This device was invented in 1954 by Luigi Ferraro, fitted as standard on every Cressi-sub mask with integrated breathing tubes and granted US patent 2,815,751 on 10 December 1957.[62]

- C. Sliding float valve to prevent water ingress when submerged. This device was used on Britmarine brand snorkels manufactured by the Haffenden company in Sandwich, Kent during the 1960s.

Integrated snorkels must be fitted with valves to shut off the snorkel's air inlet when submerged. Water will otherwise pour into the opening at the top and flood the interior of the mask. Snorkels are attached to sockets on the top or the sides of the mask.

The skirt of the diving mask attached to the snorkel is made of rubber, or latterly silicone. Older-generation snorkel masks come with a single oval, round or triangular lens retained by a metal clamp in a groove within the body of the mask. An adjustable head strap or harness ensures a snug fit on the wearer's face. The body of a mask with full-face coverage is fitted with a chinpiece to enable a complete leaktight enclosure of the mouth.

Older proprietary designs came with special facilities. One design separated the eyes and the nose into separate mask compartments to reduce fogging. Another enabled the user to remove integrated snorkels and insert plugs instead, thus converting the snorkel-mask into an ordinary diving mask. New-generation snorkel-masks enclose the nose and the mouth within an inner mask at the demand end directly connected to the single snorkel with its valve at the supply end.

Half face snorkel masks

Half-face snorkel-masks are standard diving masks featuring built-in breathing tubes topped with shut-off valves. They cover the eyes and the nose only, excluding the mouth altogether. The integral snorkels enable swimmers to keep their mouths closed, inhaling and exhaling air through their noses instead, while they are at, or just below, the surface of the water. When the snorkel tops submerge, their valves are supposed to shut off automatically, blocking nasal respiration and preventing mask flooding.

Apart from the integral tubes and their sockets, older half-face snorkel-masks were generally supplied with the same lenses, skirts and straps fitted to standard diving masks without snorkels. Several models of this kind could even be converted to standard masks by replacing their detachable tubes with air- and water-tight plugs. Conversely, the 1950s Typhoon Super Star[63] and the modern-retro Fish Brand M4D[64] standard masks came topped with sealed but snorkel-ready sockets. The 1950s US Divers "Marino" hybrid comprised a single snorkel mask with eye and nose coverage only and a separate snorkel for the mouth.[65]

There are numerous mid-twentieth-century examples of commercial snorkel-masks covering the eyes and the nose only. New-generation versions remain relatively rare commodities in the early twenty-first century.

Full face snorkel masks

Most, but not all, existing new-generation snorkel-masks are full-face masks covering the eyes, the nose and the mouth. They enable surface snorkellers to breathe nasally or orally and may be a workaround in the case of surface snorkellers who gag in response to the presence of standard snorkel mouthpieces in their mouths. Some first-generation commercial snorkel-masks were full-face masks covering the eyes, nose and mouth, while others excluded the mouth, covering the eyes and the nose only.

Full face snorkel masks use an integral snorkel with separate channels for intake and exhaled gases theoretically ensuring the user is always breathing untainted fresh air whatever the respiratory tidal volume. The main difficulty or danger is that it must fit the whole face perfectly and since no two faces are the same shape, it should be used with great care and in safe water. In the event of accidental flooding, the whole mask must be removed to continue breathing. Unless the snorkeler is able to equalize without pinching their nose it can only be used on the surface, or a couple of feet below since the design makes it impossible to pinch the nose in order to equalise pressure at greater depth.

As a result of a short period with an unusually high number of snorkeling deaths in Hawaii[66] there is some suspicion that the design of the masks can result in buildup of excess CO2. It is far from certain that the masks are at fault, but the state of Hawaii has begun to track the equipment being used in cases of snorkeling fatalities. Besides the possibility that the masks, or at least some brands of the mask, are a cause, other theories include the possibility that the masks make snorkeling accessible to people who have difficulty with traditional snorkeling equipment. That ease of access may result in more snorkelers who lack experience or have underlying medical conditions, possibly exacerbating problems that are unrelated to the type of equipment being used.[67]

During the current 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic related shortages, full-face snorkel masks have been adapted to create oxygen dispensing emergency respiratory masks by deploying 3D printing and carrying out minimal modifications to the original mask.[68][69][70] Italian healthcare legislation requires patients to sign a declaration of acceptance of use of an uncertified biomedical device when they are given the modified snorkel mask for respiratory support interventions in the country's hospitals. France's main sportwear and snorkel masks producer Decathlon has discontinued its sale of snorkel masks, redirecting them instead toward medical staff, patients and 3D printer operations.[71]

References

- Steve Blount and Herb Taylor, The Joy of Snorkeling, New York, NY: Pisces Book Company, 1984, p. 21.

- British Standards Institution: BS EN 1972: Diving equipment - Snorkels - Requirements and test methods, London: British Standards Institution, 2015.

- CMAS Finswimming Rules Version 2017/01, p. 6. Retrieved on 19 February 2019 at http://www.cmas.org/finswimming/documents-of-the-finswimming-commission.

- R. Stigler, "Die Taucherei" in Fortschritte der naturwissenschaftlichen Forschung, IX. Band, Berlin/Wien, 1913.

- Underwater World, Unit 3- Diving Skills. Retrieved on 28 February 2019 at https://www.diveunderwaterworld.com/s/Chapter-3-Diving-Skills.pdf.

- Snorkel Ken, "Full Face Snorkel Mask Reviews | Tribord EasyBreathe Alternatives and Best Prices". Retrieved on 3 March 2019 at https://snorkelstore.net/full-face-snorkel-mask-review-lower-price-lower-quality/.

- US patent 5,404,872, Splash-guard for snorkel tubes, April 11, 1995. Retrieved on 1 March 2019 at https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/01/fe/9a/6038e50865f3f1/US5404872.pdf.

- Finswimming snorkels. Retrieved on 1 March 2019 at https://monofin.co.uk/blog-snorkels.html

- Snorkel Care. Retrieved on 1 March 2019 at https://www.scubadoctor.com.au/care-snorkel.htm.

- NOAA Diving Program (U.S.) (December 1979). "4 - Diving equipment". In Miller, James W. (ed.). NOAA Diving Manual, Diving for Science and Technology (2nd ed.). Silver Spring, Maryland: US Department of Commerce: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean Engineering. p. 24.

- Ogle, W. "Aristotle on the parts of animals, tr. with notes by W. Ogle". Internet Archive. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

Just then as divers are sometimes provided with instruments for respiration, through which they can draw air from above the water, and thus may remain for a long time under the sea, so also have elephants been furnished by nature with their lengthened nostril; and, whenever they have to traverse the water, they lift this up above the surface and breathe through it.

- British Library: Online gallery. Leonardo da Vinci. Diving Apparatus, http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/features/leonardo/diving.html. Retrieved on 13 February 2019.

- Buceo Ibérico: El traje de buceo de Leonardo da Vinci, http://www.buceoiberico.com/mundo-submarino/el-traje-de-buceo-de-leonardo-da-vinci/. Retrieved on 13 February 2019.

- Gilbert Doukan: World Beneath the Waves, New York, NY: John De Graff, Inc, 1957, p. 23. Full-text document retrieved on 20 February 2019 at https://archive.org/stream/worldbeneaththew009216mbp/worldbeneaththew009216mbp_djvu.txt.

- See, for example, Faustolo Rambelli: "Sulle maschere da sub, e qualche autorespiratore, ante II G. M.", HDS Notizie No. 28 November 2003, p. 19. Retrieved on 20 February 2019 at https://www.hdsitalia.org/sites/www.hdsitalia.org/files/documenti/HDSN28.pdf.

- French Patent 736745: Masque respiratoire pour faciliter l'exercice de la natation, https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/originalDocument?CC=FR&NR=736745A&KC=A&FT=D&ND=3&date=19321128&DB=&locale=en_EP#. Retrieved on 5 July 2022.

- US Patent 1,845,263: Swimming device, https://worldwide.espacenet.com/publicationDetails/originalDocument?CC=US&NR=1845263A&KC=A&FT=D&ND=3&date=19320216&DB=&locale=en_EP#. Retrieved on 25 October 2019.

- US Patent 1,901,219, Breathing apparatus, https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/4c/e6/a1/929022724fa381/US1901219.pdf. Retrieved on 27 February 2019.

- Alain Perrier: 250 Réponses aux questions du plongeur curieux, Editions de Gerfaut, 2008, p. 70.

- Un masque français révolutionnaire. Retrieved on 18 February 2019 at https://le-scaphandrier.blog4ever.com/un-masque-francais-revolutionnaire.

- Le Scaphandre, découverte d'un nouveau monde. Retrieved on 19 February 2019 at http://cmaexpositions.canalblog.com/archives/2017/10/02/35731257.html.

- US Patent 2,317,237: Swimmer's mask, https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/ac/ac/62/5802eccace1c6f/US2317237.pdf. Retrieved on 13 February 2019.

- US Design Patent 138,286, Swimmer's mask, https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/3c/a0/78/52b889e518fbd1/USD138286.pdf. Retrieved on 13 February 2019.

- "Underwater swimming equipment", Consumer Reports, Vol. 22 No. 7 (July 1957), pp. 324-330.

- Adam Hopkins: "Into the undersea world", The Sunday Times, 20 December 1973, p. 45.

- Arrêté du 2 août 1989 portant suspension de la fabrication, de l’importation, de la mise sur le marché et ordonnant le retrait des masques de plongée comportant un tube incorporé muni d’une balle de ping-pong, https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jo_pdf.do?id=JORFTEXT000000300898. Retrieved on 13 February 2019.

- Masks. https://web.archive.org/web/20090610065300fw_/http://www.majorcasub.gr/en/profilen.htm Retrieved on 25 June 2022.

- "Balco Mask 558". www.fishingmegashop.com. Retrieved 19 February 2019.

- US Design Patent 775,722, Mask with snorkel, https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/c7/05/bd/f253e240db3b0a/USD775722.pdf. Retrieved on 13 February 2019.

- French patent 847848, Masque pour l'exploration sous-marine avec visibilité normale et toutes autres applications Brevet d'invention, Ministère du Commerce et de l'Industrie, France.

- Pierre de Latil (1949) "Masques et respirateurs sous-marins", Le Chasseur Français N°630, August 1949, p. 621. Retrieved on 13 February 2019 at http://perso.numericable.fr/cf40/articles/4849/4849621A.htm

- "Forum der Historischen Tauchergesellschaft e.V. • Thema anzeigen - Erste Einglasmaske, ab wann?". forum.historische-tauchergesellschaft.de. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Divernet: The ripping-off of Maxime's mask. Retrieved on 13 February 2019 at http://archive.divernet.com/general-diving/p302270-the-ripping-off-of-maximes-mask.html

- HUMAN SUBMARINE Shoots Fish with Arrows (Jul. 1939). https://web.archive.org/web/20150916191842/http://blog.modernmechanix.com/human-submarine-shoots-fish-with-arrows/. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- "De 'UN EQUIPO GENERADOR DE GAS (GASÓGENO)…' a 'UN PROCEDIMIENTO DE FABRICAR…". patentados.com. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- "Combined mask-tube", Neptune, Vol. 1 No. 3 (January 1956), p. 23.

- US Patent 2,317,236, Breathing apparatus for swimmers, https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/63/40/8a/e556c7ec105900/US2317236.pdf. Retrieved on 13 February 2019.

- Robert Devaux: Initiation à la chasse sous-marine, Cannes: Imprimerie Robaudy, 1947, p. 64.

- Bret Gilliam: Dick Bonin, founder of Scubapro. Retrieved on 17 February 2019 at https://www.tdisdi.com/diving-pioneers-and-innovators/dick-bonin/.

- US Divers 1964 catalogue. Retrieved on 17 February 2019 from Gear info: Manuals and Catalogs at http://www.vintagedoublehose.com/forum/.

- Dacor diving equipment guide 1968. Retrieved on 17 February 2019 at http://www.cg-45.com/downloads/download.php?file=Catalogs/DACOR/Dacor%201968.pdf.

- John E. Alexander: "Allergic reactions to mask skirts, regulator mouthpieces and snorkel mouthpieces", Journal of the South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Vol. 7 No. 2 (1977), pp. 44-45. Retrieved on 16 February 2019 at http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/6144/SPUMS_V7N2_10.pdf.

- Honolulu Star-Bulletin (Honolulu, Hawaii), Friday, November 10, 1950, p. 21.

- Skin Diver First Issue. http://www.divinghistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/skin-diver-first-issue-1951.pdf. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- Albert VanderKogel with Rex Lardner: Underwater sport, New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1955, pp. 22-26.

- Alan Broadhurst: "Let's get it right", Triton Vol. 2 No. 3 (May–June 1957), pp. 20-21. G. F. Brookes: "Watch your language", Triton Vol. 2 No. 4 (July–August 1957), p. 12.

- "Snorkel". www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- British Standards Institution: BS 4532: Specification for snorkels and face masks. London: British Standards Institution, 1969. Amendment Slip No. 1 to BS 4532:1969 Snorkels and face masks, 30 December 1977.

- Deutsches Institut für Normung: DIN 7878: Tauch-Zubehör: Schnorchel. Maße. Anforderungen. Prüfung (Diving accessories for skin divers; snorkel; technical requirements of safety, testing), Berlin/Cologne: Beuth Verlag, 1980.

- Deutsches Institut für Normung: DIN 7878: Tauch-Zubehör: Schnorchel. Sicherheitstechnische Anforderungen und Prüfung (Diving accessories for skin divers; snorkel; safety requirements and testing), Berlin/Cologne: Beuth Verlag, 1991.

- Austrian Standards International: ÖNORM S 4223: Tauch-Zubehör; Schnorchel; Abmessungen, sicherheitstechnische Anforderungen, Prüfung, Normkennzeichnung. Diving accessories; snorkel; dimensions, safety requirements, testing, marking of conformity, Vienna: Austrian Standards International, 1988.

- British Standards Institution: BS EN 1972: Diving accessories - Snorkels - Safety requirements and test methods, London: British Standards Institution, 1997.

- PADI Diver Manual. Santa Ana, CA: PADI, 1983, p. 17.

- P. P. Serebrenitsky: Техника подводного спорта, Lenizdat, 1969, p. 92. Full text retrieved on 22 February 2019 at http://ilovediving.ru/articles/maski-polumaski-ochki-dykhatelnye-trubki-lasty.

- "Folding Snorkel - is a Collapsible One for You? Fold It up and Put It Away". www.scuba-diving-smiles.com. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Ameo Powerbreather – Unique Twin Tube Fresh Air Training Snorkel Review. https://swimmingwithoutstress.co.uk/2019/08/07/ameo-powerbreather-unique-twin-tube-fresh-air-training-snorkel-review/. Retrieved 25 June 2022.

- "Phelps | Swimming Gear | Competitive Swim Store". www.michaelphelps.com. Retrieved 22 February 2019.

- Simon Codrington: Guide to underwater hunting, London: Adlard Coles, 1954, pp. 17-18.

- Cornel Lumière: Beneath the seven seas, London: Hutchinson, 1956, pp. 18-20, 30.

- Peter Small: Your guide to underwater adventure, London: Lutterworth Press, 1957, p. 5.

- Early Mfg. & Retailers - Florida Frogman No.19. Retrieved on 26 February 2019 at http://www.skindivinghistory.com/mfg_retailers/f/Florida_Frogman/19.html.

- US Patent US2815751: Breathing valve for a submarine mask. Retrieved on 27 February 2019 at https://patentimages.storage.googleapis.com/59/03/10/480531a12da43d/US2815751.pdf.

- The Diving Mask. Retrieved on 24 February 2020 at http://blutimescubahistory.com/sites/default/files/cataloghi-completi/TYPHOON%201956%20-%203.jpg.

- M4D. Retrieved on 24 February 2020 at http://www.ycdiving.com/YC2013/?product=m4d.

- Early Mfg. & Retailers - US Divers No.43. Retrieved on 26 February 2019 at http://www.skindivinghistory.com/mfg_retailers/u/US_Divers/43.html.

- "Full Face Snorkel Mask Dangers : What's all the Hub Bub, Bub? -". 11 May 2019.

- "Increasingly popular full-face snorkel masks raise safety concerns - CBS News". CBS News. 14 March 2018.

- Opoczynski, David (23 March 2020). "Coronavirus : quand les inventeurs viennent à la rescousse des hôpitaux". leparisien.fr. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Video: Emergency mask for hospital ventilators. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Easy COVID 19 emergency mask for hospital ventilators. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Vidéo : Pourquoi ne pas distribuer des masques de plongée Décathlon? BFMTV répond à vos questions. Retrieved 1 April 2020.