Genocide Convention

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or the Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to pursue the enforcement of its prohibition. It was the first legal instrument to codify genocide as a crime, and the first human rights treaty unanimously adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, on 9 December 1948, during the third session of the United Nations General Assembly.[1] The Convention entered into force on 12 January 1951 and has 152 state parties as of 2022.

| Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide | |

|---|---|

| Signed | 9 December 1948 |

| Location | Palais de Chaillot, Paris, France |

| Effective | 12 January 1951 |

| Signatories | 39 |

| Parties | 152 (complete list) |

| Depositary | Secretary-General of the United Nations |

| Full text | |

The Genocide Convention was conceived largely in response to World War II, which saw atrocities such as the Holocaust that lacked an adequate description or legal definition. Polish-Jewish lawyer Raphael Lemkin, who had coined the term genocide in 1944 to describe Nazi policies in occupied Europe and the Armenian genocide, campaigned for its recognition as a crime under international law.[2] This culminated in 1946 in a landmark resolution by the General Assembly that recognized genocide as an international crime and called for the creation of a binding treaty to prevent and punish its perpetration.[3] Subsequent discussions and negotiations among UN member states resulted in the CPPCG.

The Convention defines genocide as any of five "acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group." These five acts were: killing members of the group, causing them serious bodily or mental harm, imposing living conditions intended to destroy the group, preventing births, and forcibly transferring children out of the group. Victims are targeted because of their real or perceived membership of a group, not randomly.[4] The convention further criminalizes complicity, attempt, or incitement of its commission'. Member states are prohibited from engaging in genocide and obligated to pursue the enforcement of this prohibition. All perpetrators are to be tried regardless of whether they are private individuals, public officials, or political leaders with sovereign immunity.

The CPPCG has influenced law at both the national and international level. Its definition of genocide has been adopted by international and hybrid tribunals, such as the International Criminal Court, and incorporated into the domestic law of several countries.[5] Its provisions are widely considered to be reflective of customary law and therefore binding on all nations whether or not they are parties. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) has likewise ruled that the principles underlying the Convention represent a peremptory norm against genocide that no government can derogate.[6] The Genocide Convention authorizes the mandatory jurisdiction of the ICJ to adjudicate disputes, leading to international litigation such as the Rohingya genocide case and dispute over the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Definition of genocide

Article 2 of the Convention defines genocide as

... any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group, as such:

- (a) Killing members of the group;

- (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 2[7]

Article 3 defines the crimes that can be punished under the convention:

- (a) Genocide;

- (b) Conspiracy to commit genocide;

- (c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

- (d) Attempt to commit genocide;

- (e) Complicity in genocide.

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 3[7]

The convention was passed to outlaw actions similar to the Armenian genocide and the Holocaust.[8]

The first draft of the Convention included political killing, but the USSR[9] along with some other nations would not accept that actions against groups identified as holding similar political opinions or social status would constitute genocide,[10] so these stipulations were subsequently removed in a political and diplomatic compromise.

Early drafts also included acts of cultural destruction in the concept of genocide, but these were opposed by former European colonial powers and some settler countries.[11] Such acts, which Lemkin saw as part and parcel of the concept of genocide, have since often been discussed as cultural genocide (a term also not enshrined in international law). In June 2021, the International Criminal Court issued new guidelines for how cultural destruction, when occurring alongside other recognized acts of genocide, can potentially be corroborating evidence for the intent of the crime of genocide.[12]

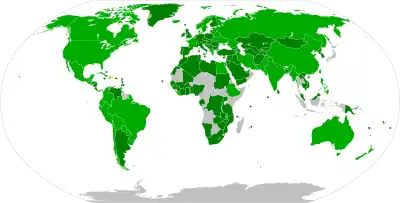

Parties

As of May 2021, there are 152 state parties to the Genocide Convention—representing the vast majority of sovereign nations—with the most recent being Mauritius, on 8 July 2019; one state, the Dominican Republic, has signed but not ratified the treaty. Forty-four states have neither signed nor ratified the convention.

Despite its delegates playing a key role in drafting the convention, the United States did not become a party until 1988—a full forty years after it was opened for signature—and did so only with reservations precluding punishment of the country if it were ever accused of genocide. These were due to traditional American suspicion of any international authority that could override US law. U.S. ratification of the convention was owed in large party to campaigning by Senator William Proxmire, who addressed the Senate in support of the treaty every day it was in session between 1967 and 1986.[13]

Immunity from prosecutions

Several parties conditioned their ratification of the Convention on reservations that grant immunity from prosecution for genocide without the consent of the national government:[14][15]

| Parties making reservations from prosecution | Note |

|---|---|

| Opposed by Netherlands, United Kingdom | |

| Opposed by Netherlands, United Kingdom | |

| Opposed by Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Turkey and United Kingdom | |

| Opposed by United Kingdom | |

| Opposed by United Kingdom |

Application to non-self-governing territories

Any Contracting Party may at any time, by notification addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, extend the application of the present Convention to all or any of the territories for the conduct of whose foreign relations that Contracting Party is responsible

— Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, Article 12[7]

Several countries opposed this article, considering that the convention automatically also should apply to Non-Self-Governing Territories:

Albania

Albania Belarus

Belarus Bulgaria

Bulgaria Hungary

Hungary Mongolia

Mongolia Myanmar

Myanmar Poland

Poland Romania

Romania Russian Federation

Russian Federation Ukraine

Ukraine

The opposition of those countries were in turn opposed by:

.svg.png.webp) Australia

Australia.svg.png.webp) Belgium

Belgium Brazil

Brazil Ecuador

Ecuador China

China Netherlands

Netherlands Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka United Kingdom

United Kingdom

(However, exceptionally, Australia did make such a notification at the same time as the ratification of the convention for Australia proper, 8 July 1949, with the effect that the convention did apply also to all territories under Australian control simultaneously, as the USSR et alii had demanded. The European colonial powers in general did not then make such notifications.)

Litigation

United States

One of the first accusations of genocide submitted to the UN after the Convention entered into force concerned the treatment of Black Americans. The Civil Rights Congress drafted a 237-page petition arguing that even after 1945, the United States had been responsible for hundreds of wrongful deaths, both legal and extra-legal, as well as numerous other supposedly genocidal abuses. Leaders from the Black community and left activists William Patterson, Paul Robeson, and W. E. B. Du Bois presented this petition to the UN in December 1951. It was rejected as a misuse of the intent of the treaty.[16] Charges under We Charge Genocide entailed of Lynching of more than 10,000 African Americans with an average of more than 100 per year- with full number could not be confirmed at the time due to unreported murder cases.[17]

Former Yugoslavia

The first state and parties to be found in breach of the Genocide convention were Serbia and Montenegro, and numerous Bosnian Serb leaders. In Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro, the International Court of Justice presented its judgment on 26 February 2007. It cleared Serbia of direct involvement in genocide during the Bosnian war. International Tribunal findings have addressed two allegations of genocidal events, including the 1992 Ethnic Cleansing Campaign in municipalities throughout Bosnia, as well as the convictions found in regards to the Srebrenica Massacre of 1995 in which the tribunal found, "Bosnian Serb forces committed genocide, they targeted for extinction, the 40,000 Bosnian Muslims of Srebrenica ... the trial chamber refers to the crimes by their appropriate name, genocide ...". Individual convictions applicable to the 1992 Ethnic Cleansings have not been secured however. A number of domestic courts and legislatures have found these events to have met the criteria of genocide, and the ICTY found the acts of, and intent to destroy to have been satisfied, the "Dolus Specialis" still in question and before the MICT, UN war crimes court,[18][19] but ruled that Belgrade did breach international law by failing to prevent the 1995 Srebrenica genocide, and for failing to try or transfer the persons accused of genocide to the ICTY, in order to comply with its obligations under Articles I and VI of the Genocide Convention, in particular in respect of General Ratko Mladić.[20][21]

Myanmar

Myanmar has been accused of Genocide against its Rohingya community in Rakhine State after around 800,000 Rohingya fled at gunpoint to neighbouring Bangladesh in 2016 and 2017, while their home villages were systematically burned. The International Court of Justice has given its first circular in 2018 asking Myanmar to protect its Rohingya from genocide.[22][23][24] Myanmar's civilian government was overthrown by the military on 1 February 2021; since the military is widely seen as the main culprit of the genocide, the coup presents a further challenge to the ICJ.

Ukraine

Russian accusations of genocide by Ukraine

In February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine, claiming that it acted, among other reasons, in order to protect Russian-speaking Ukrainians from genocide. The unfounded and false Russian charge that has been widely condemned, and has been called by genocide experts accusation in a mirror, a powerful, historically recurring, form of incitement to genocide.[25]

Russian atrocities in Ukraine

Russian forces committed numerous atrocities and war crimes in Ukraine, including all five of the potentially genocidal acts listed in the Genocide Convention. Canada, Czechia, Estonia, Ireland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine have accused Russia of genocide. In April 2022 Genocide Watch issued a genocide alert for Ukraine.[26][27] A May 2022 report by 35 legal and genocide experts concluded that Russia has violated the Genocide Convention by the direct and public incitement to commit genocide, and that a pattern of Russian atrocities implies the intent to destroy the Ukrainian national group, and the consequent serious risk of genocide triggers the obligation to prevent it on signatory states.[28][25]

See also

References

- "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide" (PDF). United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law. Retrieved 5 January 2020.

- Auron, Yair, The Banality of Denial, (Transaction Publishers, 2004), 9.

- "A/RES/96(I) - E - A/RES/96(I) -Desktop". undocs.org. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- "Genocide Background". United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect.

- "United Nations Office on Genocide Prevention and the Responsibility to Protect". www.un.org. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- "The Genocide Convention – Israel Legal Advocacy Project". 21 January 2020. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide". OHCHR. 9 December 1948. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- The Armenian Genocide and International Law, Alfred de Zayas – "And yet there are those who claim that the Armenians have no justiciable rights, because the Genocide Convention was only adopted 1948, more than thirty years after the Armenian genocide, and because treaties are not normally applied retroactively. This, of course, is a fallacy, because the Genocide Convention was drafted and adopted precisely in the light of the Armenian genocide and in the light of the Holocaust."

- Robert Gellately & Ben Kiernan (2003). The Specter of Genocide: Mass Murder in Historical Perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 267. ISBN 0-521-52750-3.

where Stalin was presumably anxious to avoid his purges being subjected to genocidal scrutiny.

- Staub, Ervin (1989). The Roots of Evil: The Origins of Genocide and Other Group Violence. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-521-42214-0.

- C. Luck, Edward (2018). "Cultural Genocide and the Protection of Cultural Heritage. J. Paul Getty Trust Occasional Papers in Cultural Heritage Policy Number 2, 2018" (PDF). J Paul Getty Trust. p. 24.

Current or former colonial powers—Belgium, Denmark, France, Netherlands, and the United Kingdom—opposed the retention of references to cultural genocide in the draft convention. So did settler countries that had displaced indigenous peoples but otherwise were champions of the development of international human rights standards, including the United States, Canada, Sweden, Brazil, New Zealand, and Australia.

- International Criminal Court (ICC), Office of the Prosecutor. "Policy on Cultural Heritage" (PDF). ICC.

- "U.S. Senate: William Proxmire and the Genocide Treaty". www.senate.gov. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- Prevent Genocide International: Declarations and Reservations to the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide

- United Nations Treaty Collection: Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide Archived 20 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, STATUS AS AT: 1 October 2011 07:22:22 EDT

- John Docker, "Raphaël Lemkin, creator of the concept of genocide: a world history perspective", Humanities Research 16(2), 2010.

- "UN Asked to Act Against Genocide in the United States". The Afro-American. 22 December 1951. Retrieved 18 October 2022.

{{cite magazine}}: Cite magazine requires|magazine=(help) - Chambers, The Hague. "ICTY convicts Ratko Mladić for genocide, war crimes and crimes against humanity | International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia". www.icty.org.

- Hudson, Alexandra (26 February 2007). "Serbia cleared of genocide, failed to stop killing". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2 March 2007.

- "ICJ:Summary of the Judgment of 26 February 2007 – Bosnia v. Serbia". Archived from the original on 5 June 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- Court Declares Bosnia Killings Were Genocide The New York Times, 26 February 2007. A copy of the ICJ judgement can be found here Archived 28 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Top UN court orders Myanmar to protect Rohingya from genocide". UN News. 23 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- "Interview: Landmark World Court Order Protects Rohingya from Genocide". Human Rights Watch. 27 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

- Paul, Stephanie van den Berg, Ruma (23 January 2020). "World Court orders Myanmar to protect Rohingya from acts of genocide". Reuters. Retrieved 20 January 2021.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Independent Legal Analysis of the Russian Federation's Breaches of the Genocide Convention in Ukraine and the Duty to Prevent" (PDF). New Lines Institute for Strategy and Policy; Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights. 27 May 2022. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 June 2022. Retrieved 22 July 2022.

- "Genocide Emergency Update: Ukraine". Genocide Watch. 13 April 2022.

- "Genocide Emergency: Ukraine". Genocide Watch. 4 September 2022.

- "Russia is guilty of inciting genocide in Ukraine, expert report concludes". the Guardian. 27 May 2022. Retrieved 24 December 2022.

Further reading

- Tams, Christian J.; Berster, Lars; Schiffbauer, Björn (2014). Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide – A Commentary, C.H. Beck / Nomos / Hart Publishing, ISBN 978-3-4066-0317-4

- Henham, Ralph J.; Chalfont, Paul; Behrens, Paul (Editors 2007). The criminal law of genocide: international, comparative and contextual aspects, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., ISBN 0-7546-4898-2, ISBN 978-0-7546-4898-7 p. 98

- Weiss-Wendt, Anton (2017). The Soviet Union and the Gutting of the UN Genocide Convention. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 978-0-299-31290-9.

- Introductory note by William Schabas and procedural history note on the Genocide Convention in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law