CRYBB1

Beta-crystallin B1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the CRYBB1 gene.[5][6] Variants in CRYBB1 are associated with autosomal dominant congenital cataract. [7][8]

| CRYBB1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | CRYBB1, CATCN3, CTRCT17, crystallin beta B1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 600929 MGI: 104992 HomoloGene: 1423 GeneCards: CRYBB1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Crystallins are separated into two classes: taxon-specific, or enzyme, and ubiquitous. The latter class constitutes the major proteins of vertebrate eye lens and maintains the transparency and refractive index of the lens. Since lens central fiber cells lose their nuclei during development, these crystallins are made and then retained throughout life, making them extremely stable proteins.

Mammalian lens crystallins are divided into alpha, beta, and gamma families; beta and gamma crystallins are also considered as a superfamily. Alpha and beta families are further divided into acidic and basic groups. Seven protein regions exist in crystallins: four homologous motifs, a connecting peptide, and N- and C-terminal extensions.

Beta-crystallins, the most heterogeneous, differ by the presence of the C-terminal extension (present in the basic group, none in the acidic group). Beta-crystallins form aggregates of different sizes and are able to self-associate to form dimers or to form heterodimers with other beta-crystallins. This gene, a beta basic group member, undergoes extensive cleavage at its N-terminal extension during lens maturation. It is also a member of a gene cluster with beta-A4, beta-B2, and beta-B3.[6]

References

- GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000100122 - Ensembl, May 2017

- GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000029343 - Ensembl, May 2017

- "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- Hulsebos TJ, Gilbert DJ, Delattre O, Smink LJ, Dunham I, Westerveld A, Thomas G, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG (Mar 1996). "Assignment of the beta B1 crystallin gene (CRYBB1) to human chromosome 22 and mouse chromosome 5". Genomics. 29 (3): 712–8. doi:10.1006/geno.1995.9947. PMID 8575764.

- "Entrez Gene: CRYBB1 crystallin, beta B1".

- Mackay DS, Boskovska OB, Knopf HL, Lampi KJ, Shiels A (Oct 2002). "A nonsense mutation in CRYBB1 associated with autosomal dominant cataract linked to human chromosome 22q". Am J Hum Genet. 71 (5): 1216–21. doi:10.1086/344212. PMC 385100. PMID 12360425.

- Siggs OM, Javadiyan S, Sharma S, Souzeau E, Lower KM, Taranath DA, et al. (June 2017). "Partial duplication of the CRYBB1-CRYBA4 locus is associated with autosomal dominant congenital cataract". Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25 (6): 711–718. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2017.33. PMC 5477362. PMID 28272538.

External links

Further reading

- David LL, Lampi KJ, Lund AL, Smith JB (1996). "The sequence of human betaB1-crystallin cDNA allows mass spectrometric detection of betaB1 protein missing portions of its N-terminal extension". J. Biol. Chem. 271 (8): 4273–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.271.8.4273. PMID 8626774.

- Lampi KJ; Ma Z; Hanson SR; et al. (1998). "Age-related changes in human lens crystallins identified by two-dimensional electrophoresis and mass spectrometry". Exp. Eye Res. 67 (1): 31–43. doi:10.1006/exer.1998.0481. PMID 9702176.

- Dunham I; Shimizu N; Roe BA; et al. (1999). "The DNA sequence of human chromosome 22". Nature. 402 (6761): 489–95. Bibcode:1999Natur.402..489D. doi:10.1038/990031. PMID 10591208.

- MacCoss MJ; McDonald WH; Saraf A; et al. (2002). "Shotgun identification of protein modifications from protein complexes and lens tissue". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (12): 7900–5. Bibcode:2002PNAS...99.7900M. doi:10.1073/pnas.122231399. PMC 122992. PMID 12060738.

- Strausberg RL; Feingold EA; Grouse LH; et al. (2003). "Generation and initial analysis of more than 15,000 full-length human and mouse cDNA sequences". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 (26): 16899–903. Bibcode:2002PNAS...9916899M. doi:10.1073/pnas.242603899. PMC 139241. PMID 12477932.

- Stempel D; Sandusky H; Lampi K; et al. (2003). "BetaB1-crystallin: identification of a candidate ciliary body uveitis antigen". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44 (1): 203–9. doi:10.1167/iovs.01-1261. PMID 12506076.

- Babenko AP, Bryan J (2004). "Sur domains that associate with and gate KATP pores define a novel gatekeeper". J. Biol. Chem. 278 (43): 41577–80. doi:10.1074/jbc.C300363200. PMID 12941953.

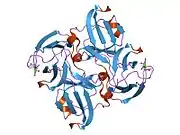

- Van Montfort RL, Bateman OA, Lubsen NH, Slingsby C (2004). "Crystal structure of truncated human betaB1-crystallin". Protein Sci. 12 (11): 2606–12. doi:10.1110/ps.03265903. PMC 2366963. PMID 14573871.

- Harms MJ; Wilmarth PA; Kapfer DM; et al. (2004). "Laser light-scattering evidence for an altered association of beta B1-crystallin deamidated in the connecting peptide". Protein Sci. 13 (3): 678–86. doi:10.1110/ps.03427504. PMC 2286738. PMID 14978307.

- Collins JE; Wright CL; Edwards CA; et al. (2005). "A genome annotation-driven approach to cloning the human ORFeome". Genome Biol. 5 (10): R84. doi:10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r84. PMC 545604. PMID 15461802.

- Gerhard DS; Wagner L; Feingold EA; et al. (2004). "The status, quality, and expansion of the NIH full-length cDNA project: the Mammalian Gene Collection (MGC)". Genome Res. 14 (10B): 2121–7. doi:10.1101/gr.2596504. PMC 528928. PMID 15489334.

- Annunziata O; Pande A; Pande J; et al. (2005). "Oligomerization and phase transitions in aqueous solutions of native and truncated human beta B1-crystallin". Biochemistry. 44 (4): 1316–28. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.330.9588. doi:10.1021/bi048419f. PMID 15667225.

- Willoughby CE; Shafiq A; Ferrini W; et al. (2006). "CRYBB1 mutation associated with congenital cataract and microcornea". Mol. Vis. 11: 587–93. PMID 16110300.

- Hou HH, Kuo MY, Luo YW, Chang BE (2006). "Recapitulation of human betaB1-crystallin promoter activity in transgenic zebrafish". Dev. Dyn. 235 (2): 435–43. doi:10.1002/dvdy.20652. PMID 16331646.

- Smith MA, Bateman OA, Jaenicke R, Slingsby C (2007). "Mutation of interfaces in domain-swapped human betaB2-crystallin". Protein Sci. 16 (4): 615–25. doi:10.1110/ps.062659107. PMC 2203347. PMID 17327390.

- Koteiche HA, Kumar MS, McHaourab HS (2007). "Analysis of betaB1-crystallin unfolding equilibrium by spin and fluorescence labeling: evidence of a dimeric intermediate". FEBS Lett. 581 (10): 1933–8. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.004. PMC 2394508. PMID 17448466.

- Cohen D; Bar-Yosef U; Levy J; et al. (2007). "Homozygous CRYBB1 deletion mutation underlies autosomal recessive congenital cataract". Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 48 (5): 2208–13. doi:10.1167/iovs.06-1019. PMID 17460281.

- Wang J; Ma X; Gu F; et al. (2007). "A missense mutation S228P in the CRYBB1 gene causes autosomal dominant congenital cataract". Chin. Med. J. 120 (9): 820–4. doi:10.1097/00029330-200705010-00015. PMID 17531125.