Electric Telegraph Company

The Electric Telegraph Company (ETC) was a British telegraph company founded in 1846 by William Fothergill Cooke and John Ricardo. It was the world's first public telegraph company. The equipment used was the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, an electrical telegraph developed a few years earlier in collaboration with Charles Wheatstone. The system had been taken up by several railway companies for signalling purposes, but in forming the company Cooke intended to open up the technology to the public at large.

The ETC had a monopoly of electrical telegraphy until the formation of the Magnetic Telegraph Company (commonly called the Magnetic) who used a different system which did not infringe the ETC's patents. The Magnetic became the chief rival of the ETC and the two of them dominated the market even after further companies entered the field.

The ETC was heavily involved in laying submarine telegraph cables, including lines to the Netherlands, Ireland, the Channel Islands, and the Isle of Man. It operated the world's first specialised cable-laying ship, the Monarch. A private line was laid for Queen Victoria on the Isle of Wight. The company was nationalised in 1870 along with other British telegraph companies, and its assets were taken over by the General Post Office.

Formation

The Electric Telegraph Company was the world's first public telegraph company, founded in the United Kingdom in 1846 by Sir William Fothergill Cooke and John Lewis Ricardo, MP for Stoke-on-Trent,[1] with Cromwell F. Varley as chief engineer.[2] Its headquarters was in Founders Court, Lothbury, behind the Bank of England.[3] This was the first company formed for the specific purpose of providing a telegraph service to the public. Besides Cooke and Ricardo, the original shareholders were railway engineer George Parker Bidder with the largest holding, Benjamin Hawes, Thomas Boulton, and three other members of the Ricardo family; Samson, Albert, and Frederick.[4]

Up to this point telegraph lines had been laid mostly in conjunction with railway companies, and Cooke had been a leading figure in convincing them of its benefits. However, these systems were all for the exclusive use of the railway company concerned, mostly for signalling purposes, until 1843 when Cooke extended the Great Western Railway's telegraph on to Slough at his own expense, at which point he acquired the right to open it to the public.[5] Railway telegraphy continued to be an important part of the company's business with expenditure on the railways peaking in 1847–48.[6] This focus on the railways was reflected in the directors and major shareholders being dominated by people associated with railway construction. Additional railway people who had become involved by 1849 included Samuel Morton Peto, Thomas Brassey, Robert Stephenson (of Rocket fame and who was chairman of the company in 1857–58), Joseph Paxton, and Richard Till, a director of several railway companies.[7]

The collaboration between Cooke and Charles Wheatstone in developing the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph was not a happy one, degenerating into a bitter dispute over who had invented the telegraph. As a result, the company was formed without Wheatstone (although he claimed he had been offered the post of scientific adviser).[8] At creation the company purchased all the patents Cooke and Wheatstone had obtained to date in building the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph.[9] It also obtained the important patent for the electric relay from Edward Davy for £600. The relay allowed telegraph signals weakened over a long distance to be renewed and retransmitted onward.[10]

Early years

The company was not immediately hugely profitable, and shares were more or less worthless.[11] In 1846 it won a concession from Belgium for telegraph lines covering the whole country. The company installed a line from Brussels to Antwerp but the traffic was light (mainly stock exchange business) and the company decided to return its concession to the Belgian Government in 1850. In 1848, after a dispute with the Great Western over an engine the ETC was alleged to have damaged, the telegraph line from Paddington to Slough was removed, although the railway company continued to use the telegraph at the Box Tunnel.[12]

The setback with the Great Western did not slow the growth of the telegraph along railway lines, and these continued to be the main source of revenue. By 1848 the company had telegraph lines along half of the railway lines then open, some 1,800 miles, and continued to make deals with more railway companies after that. These included in 1851 a new contract with Great Western which was extending its line to Exeter and Plymouth and by 1852 the ETC had installed a line that ran from London, past Slough, as far as Bristol. These contracts usually gave the company exclusive rights to install telegraph lines. This gave the company a significant advantage over competitors when other companies entered the market.[13]

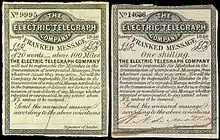

Other areas of growth were in the supply of news to newspapers, and contracts with stock exchanges. However, general use by the public was retarded by the high cost of sending a message.[14] By 1855 this situation was changing. The ETC now had over 5,200 miles of line and sent nearly three-quarters of a million messages that year. The growth, together with competitors coming on to the market, drove down prices. ETC's maximum charge for an inland telegram (over 100 miles) fell from ten shillings in 1851 to four shillings in 1855.[15]

By 1859, growth required the company to relocate its London central office to Great Bell Alley, Moorgate, but retaining the Founders Court site as a public office. The Moorgate office was arranged over three floors and a large number of men and boys were recruited on an accelerating rate of pay.[16] The company also employed a significant number of women from a higher social class as telegraphists operating the Wheatstone needle instruments. They were paid less and they had to leave if they married. A notable early employee was Maria Craig who became a supervisor.[16] The portion of Great Bell Alley east of Moorgate Street was later renamed Telegraph Street in recognition of the importance of the company at 11–14 Telegraph Street.[17] The site is now occupied by The Telegraph pub.[18]

Government reserved powers

In the Act of Parliament establishing the company, the government reserved the right to take over the resources of the ETC in times of national emergency. This it did in 1848 in response to Chartist agitation.[19] Chartism was a working-class movement for democratic reform. One of the main aims was to achieve the vote for all men over twenty-one.[20] In April 1848, the Chartists organised a large demonstration at Kennington Common and presented a petition signed by millions.[21] The government, fearing an insurrection, used its control of the ETC telegraph to disrupt Chartist communication.[22]

Competitors

The first competitor to emerge was the British Electric Telegraph Company (BETC), formed in 1849 by Henry Highton and his brother Edward.[23] The ETC had a policy of suppressing competitors by buying up rival patents. This it had done to Highton when he patented a gold-leaf telegraph instrument.[24] However, Highton now proposed a telegraph with a different system. Even worse for the ETC, in 1850 Parliament passed an Act giving it the right to force the railways to allow the BETC to construct a telegraph for government use between Liverpool and London.[25] The ETC tried to oppose the government Bill but without success.[26]

A more serious rival came in 1851 with the formation of the English and Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company (later renamed the British and Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company and usually just called the Magnetic). The Magnetic also used a non-infringing system, generating the telegraph pulses electromagnetically by the operator's own motion of working the equipment handles.[27] The Magnetic got around the ETC's dominance of rail wayleaves by using buried cables along highways,[28] a problem that had hindered the BETC and eventually led to its takeover by the Magnetic.[29] Further, it had an exclusive agreement with the Submarine Telegraph Company who had laid the first cable to France and was busily laying more cables to other continental countries.[30] The Magnetic also beat the ETC in getting the first cable to Ireland in 1853.[31] For a while then, the Magnetic had shut the ETC out of international business. The ETC was keen to correct this situation and started laying its own submarine cables.[32]

Other companies came on to the market, but ETC remained by far the largest of them with the Magnetic second. The ETC and the Magnetic so dominated the market that they were virtually a duopoly until nationalisation.[33]

Submarine cables

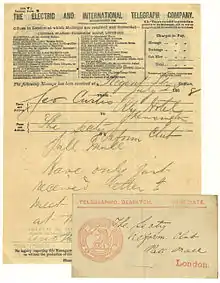

The Electric Telegraph Company merged with the International Telegraph Company (ITC) in 1854 to become the Electric and International Telegraph Company. The International Telegraph Company had been formed in 1853 for the purpose of establishing a telegraph connection to the Netherlands between Orfordness and Scheveningen using submarine telegraph cables. The concession to lay the cables had originally been granted to the ETC, but the Dutch government objected to the ETC laying landlines on its territory so a separate company, the ITC, was set up to do this. In practice, the ITC was run by ETC staff.[34] It planned to lay four separate cable cores as a diversity scheme against damage from anchors and fishing gear. All four were combined into a single cable in the sea a short distance from landing. The work was begun in 1853 with the ship Monarch, specially purchased and fitted out for the purpose, and completed in 1854. The cable proved to need a great deal of maintenance and was replaced in 1858 by a single, heavier cable made by Glass, Elliot & Co and laid by William Cory.[35]

Monarch

.png.webp)

The Monarch was the first ship to be permanently fitted out as a cable ship and operated on a full-time basis by a cable company, although the fitting out for the Netherlands cables was considered temporary.[36] She was a paddle steamer built in 1830 at Thornton-on-Tees with a 130 hp engine.[37] She was the first of a series of cable ships named Monarch.[38]

The cable laying equipment of Monarch was a major step forward compared to the unspecialised ships that had previously been used for cable laying, with sheaves to run the cable out of the hold and a powerful dedicated brake to control the cable running out. However, Monarch did not store the cable in water-filled tanks as was done on future cable ships. The ship could not, therefore, be kept in trim by replacing the cable with water as it was payed out. It was necessary to run out coils of cable alternately from the fore hold and the main hold for this reason.[39]

Besides the cables to the Netherlands, Monarch laid several cables around Britain in its first year. One of these was a cable across the Solent to the Isle of Wight. The purpose of this cable was to provide a connection to Osborne House, the summer residence of Queen Victoria.[40]

A number of improvements were made to Monarch over the years and its gear became the prototype for future cable ships. A cable picking-up machine was soon fitted with a drum that could be driven by both steam engine and manual winching, designed by the company engineer, Frederick Charles Webb. In 1857, draw-off gear was fitted to avoid crew having to hold the cable taught by hand, and water-cooled brakes were fitted in 1863.[41]

The ship was frequently chartered to other companies like the Submarine Telegraph Company and the Magnetic for cable work. The first charter was to R.S. Newall and Company to recover an abandoned cable in the Irish Sea. Newall had made this cable for the Magnetic and a failed attempt to lay it from Portpatrick in Scotland to Donaghadee in Ireland was made in 1852. Newall temporarily installed its own picking-up machine as Webb's had not yet been fitted.[42]

After nationalisation in 1870, Monarch irreparably broke down on her first cable mission for the General Post Office (GPO). She was then relegated to a coal hulk.[43]

Ireland

The chief competitor to the company, the Magnetic, had succeeded in providing the first connection to Ireland in 1853 on the Portpatrick–Donaghadee route.[44] The ETC was keen to establish its own connection. In September 1854 Monarch attempted to lay a lightweight cable from Holyhead in Wales to Howth in Ireland. This attempt was a failure, as had previous attempts on both routes with lightweight cable. In June 1855 Monarch tried again, but this time with a heavier cable made by Newall. This attempt was successful, the cable being to a similar design to the one Newall had made for the successful Magnetic cable.[45]

Another cable was laid to Ireland in 1862, this time from Wexford in Ireland to Abermawr in Wales. The cable was made by Glass, Elliot & Co and laid by Berwick.[46]

Channel Islands

A subsidiary company, the Channel Islands Telegraph Company was formed in 1857 for the purpose of providing telegraph to the Channel Islands of Jersey, Guernsey, and Alderney. The main cable was made by Newall and laid by Elba between Weymouth and Alderney in August 1858. The cable required numerous repairs due to the rocky coast of Alderney and the tidal race between Portland Bill and the Isle of Portland. The main section was finally abandoned as a maintenance liability shortly after September 1860.[47]

Isle of Man

A subsidiary company, the Isle of Man Electric Telegraph Company was formed in 1859 for the purpose of providing telegraph to the Isle of Man. The cable was made by Glass, Elliot & Co and laid by Resolute from Whitehaven.[48]

Nationalisation

The company was nationalised by the British government in 1870 under the Telegraph Act 1868 along with most other British telegraph companies.[49] The Telegraph Act 1870 extended the 1868 Act to include the Isle of Man Electric Telegraph Company and the Jersey and Guernsey Telegraph Company, but excluded the Submarine Telegraph Company and other companies which exclusively operated international cables.[50]

The Electric Telegraph Company formed the largest component of the resulting state monopoly run by the GPO.[51] In 1969 Post Office Telecommunications was made a distinct department of the Post Office,[52] and in 1981 it was separated entirely from the Post Office as British Telecom.[53] In 1984, British Telecom was privatised[54] and from 1991 traded as BT.[55]

Equipment

The primary system initially used by the company was the two-needle and one-needle Cooke and Wheatstone telegraphs. Needle telegraphs continued to be used throughout the company's existence, but printing telegraphs were also in use by the 1850s. From 1867, the ETC started to use the Wheatstone automatic duplex system. This device sent messages at an extremely fast rate from text that had been prerecorded on paper punched tape. Its advantage was that it could make maximum use of a telegraph line. This had a great economic advantage on busy long-distance lines where traffic capacity was limited by the speed of the operator. To increase traffic it would otherwise have been necessary to install expensive additional lines and employ additional operators.[56]

In 1854 the ETC installed a pneumatic tube system between its London central office and the London Stock Exchange using underground pipes. This system was later extended to other major company offices in London. Systems were also installed in Liverpool (1864), Birmingham (1865), and Manchester (1865).[57]

Historical documents

Records of the Electric Telegraph Company (33 volumes), 1846–1872, the International Telegraph Company (5 volumes), 1852–1858 and the Electric and International Telegraph Company (62 volumes), [1852]–1905 are held by BT Archives.

See also

- Time signal § United Kingdom, the ETC was the first to distribute telegraph time signals

References

- Haigh, p. 195

- Bright, p. 246

- Roberts, ch. 4

- Kieve, p. 48

- Kieve, pp. 31–32

- Kieve, pp. 44–45

- Kieve, p. 50

- Kieve, pp. 40–44

- Roberts, ch. 4

- Kieve, p. 24

- Kieve, p. 49

- Kieve, p. 48

- Kieve, pp. 49, 52

- Kieve, p. 49

- Kieve, p. 53

- Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (2004-09-23), "Maria Craig", The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford: Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/56280, retrieved 2023-08-05

- Roberts, ch. 4

- East London & City Pub History, CAMRA, accessed and archived 16 February 2019.

- Kieve, p. 50

- Chase, p. 174

- Chase, pp. 298–303

- Kieve, p. 50

- Kieve, p. 50

- Roberts, ch. 4

- Shaffner, p. 296

- Kieve, pp. 50–51

- Beauchamp, p. 77

- Bright, p. 5

- Roberts, ch. 5

- Bright & Bright, pp. 73–74

- Ash, p. 22

- Kieve, p. 52

- Hills, p. 22

- Kieve, p. 52

- Haigh, p. 195

- Haigh, p. 195

- Haigh, p. 196

- Haigh, pp. 204, 206, 211

- Haigh, p. 196

- Haigh, p. 195

- Haigh, p. 197

- Haigh, pp. 196–197

- Haigh, p. 198

- Bright, p. 14

- Haigh, p. 195

- Haigh, p. 196

- Haigh, pp. 195–196

- Haigh, p. 196

- Haigh, p. 198

- Kieve, pp. 149–159, 160

- Beauchamp, p. 74

- Pitt, p. 154

- Welch & Frémond, p. 16

- Welch & Frémond, p. 16

- Walley, p. 219

- Kieve, pp. 81–82

- Kieve, p. 82

Bibliography

- Ash, Stewart, "The development of submarine cables", ch. 1 in, Burnett, Douglas R.; Beckman, Robert; Davenport, Tara M., Submarine Cables: The Handbook of Law and Policy, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2014 ISBN 9789004260320.

- Beauchamp, Ken, History of Telegraphy, Institution of Engineering and Technology, 2001 ISBN 0852967926.

- Bright, Charles Tilston, Submarine Telegraphs, London: Crosby Lockwood, 1898 OCLC 776529627.

- Bright, Edward Brailsford; Bright, Charles, The Life Story of the Late Sir Charles Tilston Bright, Civil Engineer, Cambridge University Press, 2012 ISBN 1108052886 (first published 1898).

- Chase, Malcolm, Chartism: A New History, Manchester University Press, 2007 ISBN 9780719060878.

- Haigh, Kenneth Richardson, Cableships and Submarine Cables, Adlard Coles, 1968 OCLC 497380538.

- Hills, Jill, The Struggle for Control of Global Communication,University of Illinois Press, 2002 ISBN 0252027574.

- Kieve, Jeffrey L., The Electric Telegraph: A Social and Economic History, David and Charles, 1973 OCLC 655205099.

- McDonough, John; Egolf, Karen, The Advertising Age Encyclopedia of Advertising,

- Pitt, Douglas C., The Telecommunications Function of the British Post Office, Saxon House, 1980 ISBN 9780566002731.

- Roberts, Steven, Distant Writing, distantwriting.co.uk,

- Shaffner, Taliaferro Preston, The Telegraph Manual, Pudney & Russell, 1859.

- Walley, Wayne, "British Telecom", pp. 218–220 in, Welch, Dick; Frémond, Olivier (eds), The Case-by-case Approach to Privatization, World Bank Publications, 1998 ISBN 9780821341964.

External links

- BT Archives official site Archived 2011-02-19 at the Wayback Machine

- The BT Family Tree Archived 2011-09-06 at the Wayback Machine