Ironton, Ohio

Ironton is a city in and the county seat of Lawrence County, Ohio, United States.[4] Located in southernmost Ohio along the Ohio River, it is 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Huntington, West Virginia. The population was 10,571 at the 2020 census. Ironton is part of the Huntington–Ashland metropolitan area.

Ironton, Ohio | |

|---|---|

View of Ironton from across the Ohio River | |

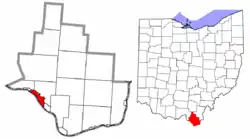

Location in Lawrence County and the State of Ohio | |

| Coordinates: 38°31′51″N 82°40′42″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Ohio |

| County | Lawrence |

| Founded | 1849 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Sam Cramblit |

| Area | |

| • City | 4.75 sq mi (12.31 km2) |

| • Land | 4.47 sq mi (11.58 km2) |

| • Water | 0.28 sq mi (0.74 km2) |

| Elevation | 551 ft (168 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 10,571 |

| • Density | 2,365.41/sq mi (913.22/km2) |

| • Metro | 288,648 |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP code | 45638 |

| Area code | 740 |

| FIPS code | 39-37464[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1076122[3] |

| Website | ironton-ohio.com |

The city's name is a contraction of "iron town", stemming from its long ties to the iron industry.[5] It also had one of the first professional football teams, the Ironton Tanks.

History

.jpg.webp)

Ironton was founded in 1849 by John Campbell,[6] a prominent pig iron manufacturer in the area. He chose the location of Ironton because of its site along the Ohio River, which would allow for water transport of iron ore to markets downriver.

Between 1850 and 1890, Ironton was one of the foremost producers of iron in the world. England, France, and Russia all purchased iron for warships from here due to the quality. Iron produced here was used for the USS Monitor, the United States' first ironclad ship.[6] More than ninety furnaces were operating at the peak of production in the late 19th century.[6]

The iron industry generated revenues that were invested in new industries, such as soap and nail production. The Detroit, Toledo and Ironton Railroad was constructed through two states, carrying iron to Henry Ford's automaking plants in Michigan. The city had a street railway, the Ironton Petersburg Street Railway, four daily newspapers, and a few foreign-language publications.[7] Ironton was also known for its accommodating attitude toward sin and vice associated with the mine and ironworkers.

Underground Railroad and Civil War

With its location on the Ohio River, Ironton became a destination on the Underground Railroad for refugee slaves seeking freedom in the North. John Campbell and some other city leaders sheltered slaves in their homes during their journeys.[8]

During the American Civil War, local military regiments were mustered, quartered, and trained at Camp Ironton, a military post located at the county fairgrounds.

Changing economics of the iron industry

The downfall of Ironton came as the market for iron changed. Also, the nation was making the transition from a demand for iron to steel. After a nationwide economic recession in the late 19th century, Ironton was no longer growing.

The Norfolk and Western Railway built a new railroad station downtown in 1906, and it continued in operation into the mid-20th century.[9] Two major floods (1917, 1937) caused extensive damage to the city and its industries. The second flood came during the Great Depression; together with the shift in the iron industry, it devastated the city. The iron industry declined, affecting other industries as well.[10] As the iron industries closed, Ironton had little with which to replace them.

An industrial city, Ironton worked to attract other heavy industry to the region. Companies such as Allied Signal and Alpha Portland Cement did build in town. The region has had difficulty creating an alternate economy.[11] By 2004, both Alpha Portland Cement and Allied Signal were gone, and Ironton had shrunk by nearly 30% from its peak population in 1950. (See US Census table below.)

Professional football and Thanksgiving Day football tradition

Ironton had one of the first professional football teams in the United States, called the Ironton Tanks. The team was organized in 1919 and played through 1930. The football field previously used by the Tanks is now home to the Ironton High School Football team, the Ironton Fighting Tigers.

The Tanks began what is now the National Football League's Thanksgiving Day Game tradition of the Detroit Lions. The Tanks played a game in 1920 the day after Thanksgiving with the Lombards, a crosstown rival, winning 26–0. In 1922, they played and defeated the Huntington Boosters 12–0 on Thanksgiving Day, Nov 30. The Tanks continued playing on this national holiday each year thru 1930, which was the Tanks final season. Several Tank players (including Glenn Presnell) continued their football careers by joining the nearby Portsmouth Spartans, who continued the annual tradition until their demise after the 1933 season.

The Spartans' assets were acquired by businessman G.A. Richards and moved to Detroit, where they were renamed the Lions. Asked by Richards about ways to improve ticket sales, the players replied that they always got a good turnout on Thanksgiving Day. He promptly scheduled the first Thanksgiving Day game in Detroit.[12]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 4.46 square miles (11.55 km2), of which 4.16 square miles (10.77 km2) is land and 0.30 square miles (0.78 km2) is water.[13]

Climate

Ironton is located within the northern limits of a humid subtropical climate (Koppen Cfa) which is typical of southern Ohio and northern Kentucky. The region experiences four distinct seasons. Winters are cool to cold with mild periods and summers are generally hot and humid, with significant precipitation year-round. Ironton is largely transitional in its plant life, sharing traditionally northern trees in landscaping like the blue spruce along with Magnolia and the occasional Needle Palm from the Upland South.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1860 | 3,691 | — | |

| 1870 | 5,686 | 54.1% | |

| 1880 | 8,857 | 55.8% | |

| 1890 | 10,939 | 23.5% | |

| 1900 | 11,868 | 8.5% | |

| 1910 | 13,147 | 10.8% | |

| 1920 | 14,007 | 6.5% | |

| 1930 | 16,021 | 14.4% | |

| 1940 | 15,851 | −1.1% | |

| 1950 | 16,333 | 3.0% | |

| 1960 | 15,745 | −3.6% | |

| 1970 | 15,030 | −4.5% | |

| 1980 | 14,178 | −5.7% | |

| 1990 | 12,751 | −10.1% | |

| 2000 | 11,211 | −12.1% | |

| 2010 | 11,129 | −0.7% | |

| 2020 | 10,571 | −5.0% | |

| 2021 (est.) | 10,434 | −1.3% | |

| Sources:[2][14][15][16] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[17] of 2010, there were 11,129 people, 4,817 households, and 2,882 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,675.2 inhabitants per square mile (1,032.9/km2). There were 5,382 housing units at an average density of 1,293.8 per square mile (499.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 92.6% White, 4.7% African American, 0.2% Native American, 0.3% Asian, 0.1% from other races, and 2.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.5% of the population.

There were 4,817 households, of which 28.1% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 39.0% were married couples living together, 15.3% had a female householder with no husband present, 5.5% had a male householder with no wife present, and 40.2% were non-families. 35.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 16.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.23, and the average family size was 2.87.

The median age in the city was 42.1 years. 21.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 8.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 23.8% were from 25 to 44; 27.1% were from 45 to 64; and 19.2% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 47.1% male and 52.9% female.

2000 census

As of the census[2] of 2000, there were 11,211 people, 4,906 households, and 3,022 families residing in the city. The population density was 2,711.3 inhabitants per square mile (1,046.8/km2). There were 5,507 housing units at an average density of 1,331.8 per square mile (514.2/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.33% White, 5.24% African American, 0.09% Native American, 0.25% Asian, 0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.09% from other races, and 0.99% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.51% of the population.

There were 4,906 households, out of which 25.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.6% were married couples living together, 14.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 38.4% were non-families. 35.3% of all households were made up of individuals, and 18.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.22, and the average family size was 2.85.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 21.8% under the age of 18, 7.9% from 18 to 24, 24.6% from 25 to 44, 24.5% from 45 to 64, and 21.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 42 years. For every 100 females, there were 82.2 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 77.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $23,585, and the median income for a family was $35,014. Males had a median income of $31,702 versus $24,190 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,391. About 17.2% of families and 23.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 32.4% of those under age 18 and 17.0% of those age 65 or over.

Arts and culture

Library

Ironton has a public library, a branch of Briggs Lawrence County Public Library.[18]

Downtown Historic District

The Downtown Ironton Historic District is listed on the National Register of Historic Places listings in Lawrence County, Ohio. The district includes Early Commercial architecture and Modern architecture representing periods from 1850 through 1974. The buildings include businesses, City Hall, financial institutions, meeting halls, United States Post Office buildings, professional service buildings and railroad industry-related structures.[19]

Memorial Day

Memorial Day events include Charity Fair, offering carnival games, crafts, inflatable rides, food, and musical acts. The Ironton-Lawrence County Memorial Day Parade, founded in 1868, is the United States oldest continuously running Memorial Day parade.[6]

Government

The city is managed by a seven-member city council, the current members of which include Chairman Chris Haney, Jacob Hock, Mike Pierce, Craig Harvey, Chris Perry, Nate Kline, and Bob Cleary.[20] Former mayor Katrina Keith was defeated in the November 2019 election by a total of 2,082 votes to 827 votes, but filed suit claiming that the winner of the election, Sam Cramblit, was not qualified to hold office in the city under state law;[21][22] the suit was dismissed by the Ohio Supreme Court in late November 2019.[23]

Education

Public education in Ironton is provided by the Ironton City School District. This includes Ironton High School (grades 9-12), Ironton Middle School (grades 6-8), and Ironton Elementary School (grades K-5).

Private education includes Saint Joseph Central High School and Saint Lawrence Central Elementary School.

Ohio University Southern Campus, the largest branch of Ohio University, is based in Ironton.[6]

Healthcare

In 2012, St. Mary's Medical Center in Huntington, West Virginia opened a campus in Ironton which includes an emergency department, imaging service, lab service, ambulance service, and helipad.[24]

Notable people

- Coy Bacon, pro football player

- George McAfee, pro football hall of fame

- Bobby Bare, country music singer

- Ritter Collett, Dayton sportswriter, winner of Spink Award from baseball's Hall of Fame

- Terry Enyart, baseball player

- Emily Jordan Folger, co-founder of the Folger Shakespeare Library

- Ken Fritz, football player

- Harlan Hatcher, eighth president of the University of Michigan

- Elza Jeffords, member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Mississippi, born in Ironton in 1826

- Mary Augusta Jordan, longtime English professor at Smith College

- Joseph Kimball (1836-1909), Civil War recipient of the Medal of Honor[25]

- William C. Lambert, achieved the second highest air victory totals for an American flying ace in World War One with 21.

- David Lively, concert pianist

- Bob Lutz, former football head coach, all-time winningest coach in Ohio high school football with 381 wins and two state championships in 1979 and 1989

- W. Terry McBrayer, Kentucky state legislature and politician

- Clint McElroy, podcaster, comic book writer, radio personality

- Butch Miles, legendary jazz drummer

- Betty Neumar, dubbed the "Black Widow" by the media for the murder of 5 of her husbands

- William Henry Powell (1825-1904), Civil War recipient of the Medal of Honor; born in Wales and entered service in Ironton[26] Powell managed the Iron works at Lawrence, Ohio.[27]

- Gardner Rea, cartoonist

- James Ancil Shipton, senior US Army officer

- Kelli Sobonya, politician

- Marion Tinsley (1927-1995), mathematician and checkers player; widely considered the greatest player of all time.

- Terry Waldo, pianist, bandleader and ragtime musician

- Nannie Kelly Wright, only known female ironmaster

References

- "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 166.

- Malloy, David E. (September 27, 2006). "Ironton". Herald-Dispatch. Huntington, WV.

- "Lawrence County: A proud past". The Tribune. July 25, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- "Lawrence County, Ohio: Community known for its rich history in iron and for its role in helping slaves escape via the Underground Railroad". The Herald-Dispatch. July 7, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2014.

- Owen, Lorrie K., ed. (1999). Dictionary of Ohio Historic Places. Vol. 2. St. Clair Shores, Michigan: Somerset. p. 857.

- Heath, Benita (January 29, 2012). "The 1937 Flood". The Tribune. Retrieved January 10, 2021.

- Payne, Phillip Gene (1994). "Modernity Lost: Ironton, Ohio in Industrial and Post-Industrial America". Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- Becker, Carl (1998). "Detroit Lions - History of the Thanksgiving day game". Home & Away: Rise & Fall Of Professional Football On Banks Of Ohio. Ohio University Press. ISBN 9780821412374.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 25, 2012. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- "Number of Inhabitants: Ohio" (PDF). 18th Census of the United States. U.S. Census Bureau. 1960. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- "Ohio: Population and Housing Unit Counts" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- "Ironton city, Ohio". census.gov. Retrieved July 1, 2022.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- "Branch hours" (PDF). Briggs Lawrence County Public Library. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- "Ohio (OH), Lawrence County". National Register of Historical Places. Nationalregisterofhistoricplaces.com. Retrieved December 3, 2013.

- "City Council". ironton-ohio.

- "Cramblit wins Ironton mayor race". The Tribune. November 6, 2019.

- Malloy, David. "Cramblit unseats Ironton mayor". The Herald-Dispatch.

- Malloy, David. "Ohio Supreme Court dismisses Ironton mayor's election challenge". The Herald-Dispatch.

- "St. Mary's Expands into Ohio With New Campus in Ironton". Archived from the original on March 16, 2016.

- "Joseph Kimball". MilitarTimes.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- "Joseph Kimball". MilitaryTimes.com. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 4, 2014.

- Robert W. Black (2004). Cavalry Raids of the Civil War. Stackpole Books. pp. 79–. ISBN 978-0-8117-3157-7.