St Mark's Campanile

St Mark's Campanile (Italian: Campanile di San Marco, Venetian: Canpanièl de San Marco) is the bell tower of St Mark's Basilica in Venice, Italy. The current campanile is a reconstruction completed in 1912, the previous tower having collapsed in 1902. At 98.6 metres (323 ft) in height, it is the tallest structure in Venice and is colloquially termed "el paròn de casa" (the master of the house).[1] It is one of the most recognizable symbols of the city.[2]

| St Mark’s Campanile | |

|---|---|

| |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Saint Mark's Square Venice, Italy |

| Coordinates | 45.4340°N 12.3390°E |

| Height | 98.6 metres (323 ft) |

| Built | ninth century–1513 |

| Rebuilt | 1902–1912 |

| Architect | Giorgio Spavento (belfry and spire) |

Located in Saint Mark's Square near the mouth of the Grand Canal, the campanile was initially intended as a watchtower to sight approaching ships and protect the entry to the city. It also served as a landmark to guide Venetian ships safely into harbour. Construction began in the early tenth century and continued sporadically over time as the tower was slowly raised in height. A belfry and a spire were first added in the twelfth century. In the fourteenth century the spire was gilded, making the tower visible to distant ships in the Adriatic. The campanile reached its full height in 1514 when the belfry and spire were completely rebuilt on the basis of an earlier Renaissance design by Giorgio Spavento. Historically, the bells served to regulate the civic and religious life of Venice, marking the beginning, pauses, and end of the work day; the convocation of government assemblies; and public executions.

The campanile stands alone in the square, near the front of St Mark's Basilica. It has a simple form, recalling its early defensive function, the bulk of which is a square brick shaft with lesenes, 12 metres (39 ft) wide on each side and 50 metres (160 ft) tall.[3] The belfry is topped by an attic with effigies of the Lion of St Mark and allegorical figures of Venice as Justice. The tower is capped by a pyramidal spire at the top of which there is a golden weather vane in the form of the archangel Gabriel.

Historical background

The Magyar raids into northern Italy in 898 and again in 899 resulted in the plundering and brief occupation of the important mainland cities of Cittanova, Padua, and Treviso as well as several smaller towns and settlements in and around the Venetian Lagoon.[4] Although the Venetians ultimately defeated the Magyars on the Lido of Albiola on 29 June 900 and repelled the incursion,[5] Venice remained vulnerable by way of the deep navigable channel that allowed access to the harbour from the sea. In particular, the young city was threatened by the Slavic pirates who routinely menaced Venetian shipping lanes in the Adriatic.[6]

A series of fortifications was consequently erected during the reign of Doge Pietro Tribuno (in office 887–911) to protect Venice from invasion by sea.[7] These fortifications included a wall that started at the rivulus de Castello (Rio del Palazzo), just east of the Doge's Castle, and eventually extended along the waterfront to the area occupied by the early Church of Santa Maria Iubanico.[note 1] However, the exact location of the wall has not been determined nor how long it was there beyond the period of crisis.[note 2][note 3]

Integral to this defensive network, an iron harbour chain that could be pulled taut across the Grand Canal to impede navigation and block access to the centre of the city was installed at the height of San Gregorio.[8][9] In addition, a massive watchtower was built in Saint Mark's Square. Probably begun during the reign of Tribuno, it was also intended to serve as a point of reference to guide Venetian ships safely into the harbour, which at that time occupied a substantial part of the area corresponding to the present-day piazzetta.[1][10][11][note 4]

Construction

Tower

The defensive system begun under Pietro Tribuno was likely provisional, and construction may have been limited to the reinforcement of pre-existing structures.[10] Medieval chronicles suggest that the laying of the foundation for the tower continued during the reigns of his immediate successors, Orso II Participazio (in office 912–932) and Pietro II Candiano (in office 932–939). Delays were likely due to the difficulty in developing suitable construction techniques as well as locating and importing building materials.[12][13][note 5] Some of the early bricks dated from the late Roman Empire and were salvaged from ruins on the mainland.[14] For the foundation, alder piles, roughly 1.5 metres (4.9 ft) in length and 26 centimetres (10 in) in diameter, were driven into a dense layer of clay located around 5 metres (16 ft) below the surface.[15][16] The piles were topped with two layers of oak planking on which multiple layers of stone were laid.[14]

Fabrication of the actual tower seems to have begun during the brief reign of Pietro Participazio (in office 939–942) but did not progress far.[13] Political strife during the ensuing reigns of Pietro III Candiano (in office 942–959) and, particularly, Pietro IV Candiano (in office 959–976) precluded further work.[13] Under Pietro I Orseolo (in office 976–978), construction resumed, and it advanced considerably during the reign of Tribuno Memmo (in office 979–991).[17] No further additions were made to the tower until the time of Domenico Selvo (in office 1071–1084), an indication that it had reached a serviceable height and could be used to control access to the city.[18] Selvo increased the height to around 40 metres (130 ft), which corresponded with the fifth of the eight present windows.[19][20] Doge Domenico Morosini (in office 1147–1156) then raised the height to the actual level of the belfry and is credited with the construction of the bell tower.[21] His portrait in the Doge's Palace shows him together with a scroll that lists the significant events of his reign, among which is the construction of the bell tower: "Sub me admistrandi operis campanile Sancti Marci construitur...".[22]

Belfry and spire

The first belfry was added under Vitale II Michiel (in office 1156–1172). It was surmounted by a pyramidal spire in wood that was sheathed with copper plates.[23][24] Around 1329, the belfry was restored and the spire reconstructed. The spire itself was particularly prone to fire due to the wooden framework. It burned when lighting struck the tower on 7 June 1388, but it was nevertheless rebuilt in wood. On this occasion, the copper plates were covered in gold leaf, rendering the tower visible to distant ships in the Adriatic.[25] Marcantonio Sabellico records in his guide to the city, De Venetae urbis situ (c. 1494), that mariners looked to the gilded spire as a 'welcoming star':

Its peak is high such that the splendour of the gold with which it is sheathed manifests itself to navigators at 200 stadions like a star that greets them. (Summus apex adeo sublimis ut fulgor auri quo illitus est ad ducenta stadia ex alto navigantibus velut saluberrimum quoddam occurrat sydus.)[26]

The spire was once again destroyed in 1403 when flames from a bonfire lit to illuminate the tower in celebration of the Venetian victory over the Genoese at the Battle of Modon enveloped the wooden frame.[25][27] It was rebuilt between 1405 and 1406.[28] Lightning again struck the tower during a violent storm on 11 August 1489, setting ablaze the spire which eventually crashed into the square below. The bells fell to the floor of the belfry, and the masonry of the tower itself cracked.[29] In response to this latest calamity, the procurators of Saint Mark de supra, the government officials responsible for the public buildings around Saint Mark's Square, decided to rebuild the belfry and spire completely in masonry so as to prevent future fires. The commission was given to their proto (consultant architect and buildings manager), Giorgio Spavento. Although the design was submitted within a few months, the estimated cost was 50,000 ducats, and financial constraints in the period of recovery from the wars in Lombardy against Milan (1423–1454) delayed construction.[30] Instead, Spavento limited repairs to the structural damage to the tower. A temporary clay-tile roof was placed over the belfry, and the bells that were still intact were rehung. The outbreak in 1494 of the Italian wars for the control of the mainland precluded any further action.[31][32]

On 26 March 1511, a violent earthquake further damaged the fragile structure and opened a long fissure on the northern side of the tower, making it necessary to immediately intervene. Upon the initiative of procurator Antonio Grimani, the temporary roof and the belfry were removed and preparations were made to finally execute Spavento's design.[33] The work was carried out under the direction of Pietro Bon who had succeeded Spavento as proto in 1509.[34][note 6] To finance the initial work, the procurators sold unclaimed objects in precious metals that had been deposited in the treasury of St Mark's in 1414 for a value of 6,000 ducats.[35][36] By 1512, the tower itself had been completely repaired, and work began on the new belfry made in Istrian stone.[37]

The four sides of the brick attic above have high-relief sculptures in contrasting Istrian stone. The eastern and western sides have allegorical figures of Venice, presented as a personification of Justice with the sword and the scales. She sits on a throne supported by lions on either side in allusion to the throne of Solomon, the king of ancient Israel renowned for his wisdom and judgement.[38] This theme of Venice as embodying, rather than invoking, the virtue of Justice is common in Venetian state iconography and is recurrent on the façade of the Doge's Palace.[39] The remaining sides of the attic have the lion of Saint Mark, the symbol of the Venetian Republic.

On 6 July 1513 a wooden statue of the archangel Gabriel, plated in copper and gilded, was placed at the top of the spire.[40] In his diary, Marin Sanudo recorded the event:

On this day, a gilded copper angel was hoisted above Saint Mark's Square at four hours before sunset to the sound of trumpets and fifes, and wine and milk were sprayed in the air as a sign of merriment. (In questo zorno, su la piazza di San Marco fo tirato l’anzolo di rame indorado suso con trombe e pifari a hore 20; et fo butado vin e late zoso in segno di alegrezza.)[41]

A novelty with respect to the earlier tower, the statue also functioned as a weather vane, turning so that it always faced into the wind.[42] Francesco Sansovino suggested in his guide to the city, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare (1581), that the idea of a weather vane atop the new tower derived from Vitruvius’ description of the Tower of the Winds in Athens which had a bronze triton mounted on a pivot.[43][44] But the specific choice of the archangel Gabriel was meant to recall the legend of Venice's foundation on the 25 March 421, the feast of the Annunciation.[note 7] In Venetian historiography, the legend, traceable to the thirteenth century, conflated the beginning of the Christian era with the birth of Venice as a Christian republic and affirmed Venice's unique place and role in history as an act of divine grace.[45] As a construct, it is expressed in the frequent representations of the Annunciation throughout Venice, most notably on the façade of St Mark's Basilica and in the reliefs by Agostino Rubini at the base of the Rialto Bridge, depicting the Virgin Mary opposite the archangel Gabriel.[46]

As recorded by Marin Sanudo, structural work on the tower terminated in June 1514.[47] The remaining work was completed by October 1514, including the gilding of the spire.[48]

Loggetta

In the fifteenth century, the procurators of Saint Mark de supra erected a covered exterior gallery attached to the bell tower. It was a lean-to wooden structure, partially enclosed, that served as a gathering place for nobles whenever they came to the square on government business. It also provided space for the procurators who occasionally met there and for the sentries who protected the entry to the Doge's Palace whenever the Great Council was in session.[49]

Over time, it was repeatedly damaged by falling masonry from the bell tower as a result of storm and earthquake but was repaired after each incident. However, when lightning struck the bell tower on 11 August 1537 and the loggia underneath was once again damaged, the decision came to completely rebuild the structure.[50] The commission was given to the sculptor and architect Jacopo Sansovino, the immediate successor to Bon as proto to the procurators of Saint Mark de supra. It was completed in 1546.[51]

The remaining three sides of the bell tower were covered with wooden lean-to stalls, destined for retail activities. These were an additional source of revenue for the procurators of Saint Mark de supra and were leased in order to finance the maintenance of the buildings in the square. The lean-to stalls were removed in 1873.[52][53]

Later history

Throughout its history, the bell tower remained susceptible to damage from storms. Lightning struck in 1548, 1562, 1565, and 1567.[54][55] On each occasion, repairs were carried out under the direction of Jacopo Sansovino, responsible as proto for the maintenance of the buildings administered by the procurators of Saint Mark de supra, including the bell tower. The work, funded from the accounts of the procurators, was typically executed by carpenters provided by the Arsenal, the government shipyards.[56] The tower was damaged twice in 1582.[57][58]

In the following centuries, it was repeatedly necessary to intervene and repair the damage caused by lightning. In 1653, Baldassarre Longhena took up repairs after lightning struck, having become proto in 1640. The damage must have been extensive on this occasion, given the repair cost of 1,230 ducats.[59] Significant work was also necessary to repair damage done after lightning struck on 23 April 1745, causing some of the masonry to crack and killing four people in the square as a result of falling stonework.[60] The campanile was again damaged by lightning in 1761 and 1762. Repair costs on the second occasion reached the considerable sum of 3,329 ducats.[61] Finally, on 18 March 1776, the physicist Giuseppe Toaldo, professor of astronomy at the University of Padua, installed a lightning rod, the first in Venice.[61][62][63]

Periodic work was also needed to repair damage to the tower and the statue of the archangel Gabriel from wind and rain erosion. The original statue was replaced in 1557 with a smaller version.[64] After numerous restorations, this was in turn substituted in 1822 by a statue designed by Luigi Zandomeneghi, professor at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia.[65]

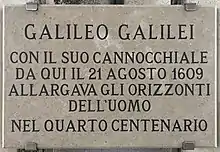

The tower remained of strategic importance to the city. Access to visiting foreign dignitaries was allowed only by the Signoria, the executive body of the government, and ideally at high tide when it was not possible to distinguish the navigable channels in the lagoon.[66] On 21 August 1609, Galileo Galilei demonstrated his telescope to the procurator Antonio Priuli and other nobles from the belfry. Three days later, the telescope was presented to doge Leonardo Donato from the loggia of the Doge's Palace.[67]

Bells

History

A bell was most likely first installed in the tower during the tenure of Doge Vitale II Michiel. However, documents that attest to the presence of a bell are traceable only from the thirteenth century. A deliberation of the Great Council, dated 8 July 1244, established that the bell to convene the council was to be rung in the evening if the council was to meet the following morning and in the early afternoon if the meeting was scheduled for the evening of the same day. There is a similar reference to the bell in the statute of the ironmongers' guild, dating to 1271.[68]

Over time, the number of bells varied. In 1489, there were at least six. Four were present in the sixteenth century until 1569 when a fifth was added. Beginning in 1678 the bell brought to Venice from Crete after the island was lost to the Ottoman Turks, called the Campanon da Candia, hung in the tower, but it fell to the floor of the belfry in 1722, and was not resuspended. After this time, five bells remained.[69] These were named (from smallest to largest) Maleficio (also Renghiera or Preghiera), Trottiera (also Dietro Nona), Meza-terza (also Pregadi), Nona, and Marangona.[70][71][72][note 8]

The historical accounts of the damage to the tower caused by lightning make reference to broken bells, an indication that the bells must have been recast at various times. Nonetheless, the first documented instance concerns the Trottiera, which was recast in 1731. The resulting sound was unsatisfactory, and the bell had to be recast two more times before it harmonized with the older bells.[73] After the designation of St Mark's Basilica as the cathedral of Venice (1807), the Marangona and Renghiera, together with the Campanon da Candia and other bells from former churches, were recast by Domenico Canciani Dalla Venezia into two larger bronze bells between 1808 and 1809, but these were melted with the Meza-terza, Trottiera, and Nona in 1820, again by Dalla Venezia, to create a new series of five bells.[74] Of these bells, only the Marangona survived the collapse of the bell tower in 1902.[75]

Functions

In various combinations, the bells indicated the times of the day and coordinated activities throughout the city. Four of the bells also had specific functions in relation to the activities of the Venetian government.[note 9]

Times of the day

At dawn, with the first appearance of daylight, the Meza-terza rang (16 series of 18 strokes).[76] The Marangona followed at sunrise (16 series of 18 strokes).[77] This signalled the opening of the Church of St Mark for prayer and of the loggetta at the base of the bell tower. The gates of the Jewish Ghetto were also opened.[78][note 10] The ringing of the Marangona also notified labourers to prepare for the workday which, determined by sunlight, varied in length throughout the year. The Marangona, the largest bell, derived its name from this particular function in reference to the marangoni (carpenters) who worked in the Arsenal.[79] After the Marangona ceased, a half hour of silence followed. The Meza-terza then rang continuously for thirty minutes.[77] The bell derived its name, Meza-terza (half third), from the time of the day since it rang between sunrise and Third Hour (Terce), the traditional moment of the liturgical mid-morning prayer.[80] At the end of the thirty minutes, holy mass was celebrated in St Mark's. Also, the workday began for the workmen in the Arsenal, the artisans da grosso (heavy mechanical trades), and government officials. Labourers who were not present for work did not receive full wages for the day. Shop hours and the workday of some artisan guilds were regulated by the Realtina, the bell located in the tower of the Church of San Giovanni Elemosinario at Rialto.[81]

| dawn | sunrise | sunrise + A + 30 min | sunrise + A + 2 hr "third hour" |

midday "ninth hour" |

midday + A + 30 min | sunset 24 hr |

sunset + 60 min | sunset + 84 min | sunset + 108 min | midnight |

| Meza-terza | Marangona | Meza-terza | Marangona | Nona | "Dietro Nona" | Marangona | Meza-terza | Nona | Marangona | Marangona |

| 16 series of 18 strokes |

16 series of 18 strokes |

30 min | 15 series of 16 strokes |

16 series of 18 strokes |

30 min | 15 series of 16 strokes |

12 min | 12 min | 12 min | 16 series of 18 strokes |

| opening of ghetto and St Mark's Basilica | at termination (=sunrise + A + 1 hr) workday begins for government, mechanical guilds, and Arsenal | beginning of work break | at termination (=midday + A + 1 hr) work break ends |

workday ends for government, mechanical guilds, and Arsenal | at termination (=sunset + 72 min) first night-watch shift present for duty in Saint Mark's Square |

at termination (=sunset + 96 min) letters to Rialto |

at termination (=sunset + 2 hr) first night-watch shift begins in Saint Mark's Square |

at termination second night-watch shift begins in Saint Mark's Square | ||

| A = the time employed to ring 16 series of 18 strokes | ||||||||||

Third Hour was signalled by the ringing of the Marangona (15 series of 16 strokes).[77]

The Nona derived its name from Ninth Hour (Nones), the traditional moment of the liturgical afternoon prayer. It sounded (16 series of 18 strokes) at midday and marked the beginning of the work break. After the Nona ceased, a half hour of silence ensued. The Trottiera then rang continuously for 30 minutes: from this particular function, the Trottiera was also termed Dietro Nona (behind, or after, Nona). When the ringing stopped, work began again.[82] An hour later, the Nona rang (9 series of 10 strokes for three times) to mark the vespertine Ave Maria which was followed by the Marangona (15 series of 16 strokes).[83]

The Marangona rang (15 series of 16 strokes) at sunset which corresponded to 24 hours and the end of the workday for the Arsenal, the heavy mechanical trades, and the government offices.[83] An hour after sunset, the Meza-terza rang for 12 minutes, signalling that the night watch was required to be present in Saint Mark's Square.[84] After a twelve-minute pause, the Nona rang for 12 minutes. This indicated that letters were to be taken to Rialto for dispatch. After another 12 minutes, the Marangona struck for 12 minutes, ending at two hours after sunset.[85] The night watch then began. The Realtina signalled the moment to extinguish fires in the homes.[note 11]

Midnight was marked by the ringing of the Marangona (16 series of 18 strokes).[86]

Public executions

The smallest bell, known alternatively as the Renghiera, Maleficio, or Preghiera, signalled public executions by ringing for 30 minutes. The bell had previously been located in the Doge's Palace and is mentioned in connection with the execution for treason of Doge Marin Falier in 1355. In 1569, it was moved to the tower. The earliest name, Renghiera, derived from renga (harangue) in reference to the court proceedings within the Palace. The alternative name of Maleficio, from malus (evil, wicked), recalled the criminal act, whereas Preghiera (prayer) invoked supplications for the soul of the condemned.[87] After the execution, the Marangona was rung for a half hour and then the Meza-terza.[88] Whenever capital punishment was ordered by the Council of Ten, the Maleficio rang immediately after the Marangona of sunrise and the sentence was carried out in the morning. Death sentences issued by the Quarantia al Criminal or the Lords of the Night were carried out in the afternoon, the Maleficio ringing immediately after the Dietro Nona ended.[89]

Convocation of government assemblies

The Marangona announced the sessions of the Great Council.[90] In the event that the council was to meet in the afternoon, the Trottiera first rang for 15 minutes, immediately after Third Hour. After midday, the Marangona resounded (4 series of 50 strokes followed by 5 of 25). The Trottiera then rang continuously for a half hour as a second call for the members of the Great Council, signalling the need to quicken the pace. The name of the bell originated when horses were used in the city. The ringing of the Trottiera was therefore meant to signal the need to proceed at a trot. When the bell ceased, the doors of the council hall were closed and the session began. No latecomers were admitted. Whenever the Great Council convened in the morning, the Trottiera rang the previous evening for 15 minutes after the Marangona marked the end of the day at sunset. The Marangona was then rung in the morning, with the prescribed series of strokes, followed by the Trottiera.[91][81]

The meetings of the Venetian Senate were announced by the Trottiera, which rang for 12 minutes. The Meza-terza followed and rang for 18 minutes. Because of this function, the Meza-terza was also known as the Pregadi, in reference to the early name of the Senate when members were 'prayed' (pregadi) to attend.[80]

Holy days and events

On solemnities and certain feast days, all the bells rang in plenum. The bells also rang in unison for three days, until three hours after sunset, to mark the election of the doge and the coronation of the pope. On these occasions, they were rapidly hammered. Two hundred lanterns were also arranged in four tiers at the height of the belfry in celebration.[92]

To announce the death of the doge and for the funeral, the bells rang in unison (9 series, each series slowly over 12 minutes). For the death of the pope, the bells rang for three days after Third Hour (6 series, each series slowly over 12 minutes).[93] The bells also marked the passing of cardinals and foreign ambassadors who had died in Venice, the dogaressa and sons of the doge, the patriarch and the canons of St Mark's, the procurators of Saint Mark, and the Grand Chancellor (the highest ranking civil servant).[94]

Custodian

The custodian of the bell tower was responsible for ringing the bells. Nominated for life by the procurators of Saint Mark de supra, he was often succeeded by his sons or, in one instance, by his widow. The salary varied over time and could include a combination of wages, lodgings in the tower, and the use, for sublet or retail activities, of one of the lean-to stalls at the base of the tower.[95]

Collapse and rebuilding (1902–1912)

Collapse

When the lean-to stalls were removed from the sides of the bell tower in 1873–1874, the base was discovered to be in poor condition, but restoration was limited to repairing surface damage. Similarly, excavations in Saint Mark's Square in 1885 raised concerns for the state of the foundation and the stability of the structure.[96] Yet inspection reports by engineers and architects in 1892 and 1898 were reassuring that the tower was in no danger. Ensuing restoration was sporadic and primarily involved the substitution of weathered bricks.[97]

In July 1902, work was underway to repair the roof of the loggetta. The girder supporting the roof where it rested against the tower was removed by cutting a large fissure, roughly 40 centimetres (16 in) in height and 30 centimetres (12 in) in depth, at the base of the tower.[98] On 7 July, it was observed that the shaft of the tower trembled as workmen hammered the new girder into place. Glass tell-tales were inserted into crevices in order to monitor the shifting of the tower. Several of these were found broken the next day.[99][100]

By 12 July, a large crack had formed on the northern side of the tower, running almost the entire height of the brick shaft. More accurate plaster tell-tales were inserted into the crevices. Although a technical commission was immediately formed, it determined that there was no threat to the structure. Nevertheless, wooden barricades were erected to keep onlookers at a safe distance as pieces of mortar began to break off from the widening gap and fall to the square below. Access to the tower was prohibited, and only the bell signalling the beginning and end of the work day was to be rung in order to limit vibrations. The following day, Sunday, the customary band in Saint Mark's Square was cancelled for the same reason.[101]

The next morning, Monday 14 July, the latest tell-tales were all discovered broken; the maximum crack that had developed since the preceding day was 0.75 centimetres (0.30 in). At 09:30 the square was ordered evacuated. Stones began to fall at 9:47, and at 9:53 the entire bell tower collapsed.[102] Subsequent investigations determined that the immediate cause of the disaster was the collapse of the access ramps located between the inner and outer shafts of the tower. Beginning at the upper levels, these fell one by one atop the others. Without their support, the outer shaft then caved in against the inner shaft.[103] Because the tower collapsed vertically and due to the tower's isolated position, the resulting damage was relatively limited. Apart from the loggetta, which was completely demolished, only a corner of the historical building of the Marciana Library was destroyed. The basilica itself was unharmed, although the pietra del bando, a large porphyry column from which laws were read, was damaged.[104] The sole fatality was the custodian's cat.[105] That same evening, the communal council convened in an emergency session and voted unanimously to rebuild the bell tower exactly as it had been before the collapse. The council also approved an initial 500,000 lire for the reconstruction.[106] The province of Venice followed with 200,000 lire on 22 July.[107] Although a few detractors of the reconstruction, including the editorialist of the Daily Express and Maurice Barrès, claimed that the square was more beautiful without the tower and that any replica would have no historical value, "dov’era e com’era" ("where it was and how it was") was the prevailing sentiment.[108]

Rebuilding

In addition to the sums appropriated by the commune and the province, a personal donation arrived from King Victor Emmanuel III and the queen mother (100,000 lire).[109] This was followed by contributions from other Italian communes and provinces as well as private citizens.[110] Throughout the world, fund raising began, spearheaded by international newspapers.[107] The German scaffolding specialist Georg Leib of Munich donated the scaffolding on 22 July 1902.[111]

In autumn 1902, work began on clearing the site. The fragments of the loggetta, including columns, reliefs, capitals, and the bronze statues, were carefully removed, inventoried, and transferred to the courtyard of the Doge's Palace. Bricks that could be used for other construction projects were salvaged, whereas the rubble of no use was transported on barges to the open Adriatic where it was dumped.[112] By spring 1903, the site had been cleared of debris, and the remaining stub of the old tower was torn down and the material removed. The pilings of the medieval foundation were inspected and found to be in good condition, requiring only moderate reinforcement.[113]

The ceremony to mark the commencement of the actual reconstruction took place on 25 April 1903, St Mark's feast day, with the blessing by the patriarch of Venice Giuseppe Sarto, later Pope Pius X, and the laying of the cornerstone by Prince Vittorio Emanuele, the count of Turin, as the king's representative.[114] For the first two years, work consisted in preparing the foundation which was extended outward by 3 metres (9.8 ft) on all sides. This was accomplished by driving in 3076 larch piles, roughly 3.8 metres (12 ft) in length and 21 centimetres (8.3 in) in diameter.[115] Eight layers of Istrian stone blocks were then placed on top to create the new foundation. This was completed in October 1905.[116] The first of the 1,203,000 bricks used for the new tower was laid in a second ceremony on 1 April 1906.[117] To facilitate construction, a mobile scaffold was conceived. It surrounded the tower on all sides and was raised as work progressed by extending the braces.[118]

With respect to the original tower, structural changes were made to provide for greater stability and decrease the overall weight. The two shafts, one inside the other, were previously independent of each other. The outer shell alone bore the entire weight of the belfry and spire; the inner shaft only partially supported the series of ramps and steps. With the new design, the two shafts were tied together by means of reinforced concrete beams which also support the weight of the ramps, rebuilt in concrete rather than masonry. In addition, the stone support of the spire was replaced with reinforced concrete, and the weight was distributed on both the inner and outer shafts of the tower.[119]

The tower itself was completed on 3 October 1908. It was then 48.175 metres (158.05 ft) in height.[120] The following year work began on the belfry and the year after on the attic. The allegorical figures of Venice as Justice on the eastern and western sides were reassembled from the fragments that had been recovered from the ruins and were restored. The twin effigies of the winged lion of Saint Mark located on the remaining sides of the attic had already been chiselled away and irreparably damaged after the fall of the Venetian Republic at the time of the first French occupation (May 1797 – January 1798). They were completely remade.[121]

Work began on the spire in 1911 and lasted until 5 March 1912 when the restored statue of the archangel Gabriel was hoisted to the summit. The new campanile was inaugurated on 25 April 1912, on the occasion of St Mark's feast day, exactly 1000 years after the foundations of the original building had allegedly been laid.[122]

New bells

| ||||

| bell | diameter | weight | note | |

| Marangona | 180 centimetres (71 in) | 3,625 kilograms (7,992 lb) | A2 | |

| Nona | 156 centimetres (61 in) | 2,556 kilograms (5,635 lb) | B2 | |

| Meza terza | 138 centimetres (54 in) | 1,807 kilograms (3,984 lb) | C3 | |

| Trottiera | 129 centimetres (51 in) | 1,366 kilograms (3,012 lb) | D3 | |

| Maleficio | 116 centimetres (46 in) | 1,011 kilograms (2,229 lb) | E3 | |

| Image: Giuseppe Cherubini, The Blessing of the Bells of St Mark's (1912) | ||||

Of the five bells cast by Domenico Canciani Dalla Venezia in 1820, only the largest, the Marangona, survived the collapse.[123]

On 14 July 1902, Pope Pius X, patriarch of Venice at the time of the collapse, announced his intention to personally finance the recasting of the four bells as a gift to the city. For the purpose, a foundry was activated near the Church of Sant'Elena, on the homonymous island. The work was carried out under the supervision of the directors of the choirs of St Mark's and St Anthony's in Padua, the director of the Milan Conservatory, and the owner of the Fonderia Barigozzi of Milan.[124] The fragments of the four bells were first assembled, and moulds were made to ensure the same sizes and shapes. The original bronze was then remelted, and the new Maleficio, Trottiera, Meza terza, and Nona were cast on 24 April 1909, the vigil of St Mark's Feast.[note 8] After two months, the bells were tuned to harmonize with the Marangona before being transported to Saint Mark's Square for storage.[125][note 12] They were formally blessed by Cardinal Aristide Cavallari, patriarch of Venice, on 15 June 1910 in a ceremony with Prince Luigi Amedeo in attendance, prior to being raised to the new belfry on 22 June.[126]

To ring the new bells, the simple rope and lever system, previously used to swing the wooden headstock, was replaced with a grooved wheel around which the rope is wrapped. This was done to minimize the vibrations whenever the bells are rung and hence the risk of damage to the tower.[121]

Elevator

In 1892, it was first proposed that an elevator be installed in the bell tower. But concerns over the stability of the structure were voiced by the Regional Office for the Preservation of Veneto Monuments (Ufficio Regionale per la Conservazione dei Monumenti del Veneto). Although a special commission was nominated and concluded that the concerns were unfounded, the project was abandoned.[127]

At the time of the reconstruction, an elevator was used to raise the new bells to the level of the belfry, but it was only temporary.[121] Finally, in 1962, a permanent elevator was installed. Located within the inner shaft, it takes 30 seconds to reach the belfry from the ground level.[128]

Restoration work (2007–2013)

At the time of the reconstruction, the original foundation was extended from approximately 220 square metres (2,400 sq ft) to 410 square metres (4,400 sq ft) with the objective of distributing the weight of the bell tower on a larger base and reducing the load from 9 kilograms (20 lb) to 4 kilograms (8.8 lb) per 1 square centimetre (0.16 in2). This was done by driving additional piles into the clay. Three layers of oak planks were then laid on top of the piles followed by multiple layers of Istrian stone blocks. However, the old and the new foundations were not successfully fused into a unified whole, and they began to subside at different rates. As a result, cracks in the new tower were already visible in 1914 and multiplied over time. A monitoring system, installed in 1995, revealed that the tower was leaning by 7 centimetres (2.8 in).[129]

Beginning in 2007, the Magistrato alle Acque, responsible for public works, reinforced the foundation, adopting a system used to consolidate the façade of St Peter's Basilica in Rome. This involved placing four titanium tension cables, 6 centimetres (2.4 in) in diameter, around the perimeter of the stone foundation. Two of the cables, placed 20 centimetres (7.9 in) apart within a single protective polyethylene tube, are located 40 centimetres (16 in) below the surface of the square and are anchored at the four corners of the foundation by titanium pillars. Two more cables are located at a depth of 2.3 metres (7.5 ft) and are held by granite blocks. These cables are monitored and can be tightened as necessary.[130] The project, initially projected to last two and half years, was completed after five years in April 2013.[131]

Influence

The campanile inspired the designs of other towers worldwide, especially in the areas belonging to the former Republic of Venice. Similar bell towers, albeit smaller, exist at the Church of San Rocco in Dolo, Italy, at the Church of San Giorgio in Piran, Slovenia, and at the Church of Sant'Eufemia in Rovinj, Croatia.[132][133][134]

in Berkeley

in Denver

in Toronto

Other towers inspired by St Mark's campanile, particularly in the aftermath of the collapse of the original tower, include:

- the mill chimney of India Mill (1867) in Darwen, Lancashire, United Kingdom[135]

- the Sretenskaya church (1892) in Bogucharovo, Tula region, Russia[136]

- the right-hand bell-tower of St. John Gualbert (1895) in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, United States[137]

- the clock tower at King Street Station (1904–1906) in Seattle, Washington, United States[138][139]

- the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower (1905–1909) in New York City, New York, United States[139][140]

- the Daniels & Fisher Tower (1910) in Denver, Colorado, United States[139][141]

- 14 Wall Street (1910–1912) in New York City, New York, United States[142]

- the Rathaus (Town Hall) (1911) in Kiel, Germany[143]

- the Custom House Tower (1913–1915) in Boston, Massachusetts, United States[144]

- the Sather Tower (1914) on the campus of the University of California, Berkeley, California, United States[139][145]

- North Toronto Station (1916) in Toronto, Canada[139][146]

- Brisbane City Hall (1920–1930) in Brisbane, Australia[139]

- the Campanile (1922–1924) in Port Elizabeth, South Africa[139][147]

- the Tribune Tower (1923–1924) in Oakland, California, United States[148]

- the Venetian Towers (1927–1929) in Barcelona, Spain[149]

- the tower at Jones Beach State Park (1930), Long Island, New York, United States[150]

- the water tower of the former Trencherfield Mill in Wigan, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom[151]

As symbols of Venice, replicas of the campanile also exist at The Venetian in Las Vegas, Nevada[152] and at its sister resort The Venetian Macao in Macao;[153] at the Italy Pavilion at Epcot, a theme park at Walt Disney World in Lake Buena Vista, Florida;[154] and at the Venice Grand Canal, Taguig in Manila, Philippines.[155]

References

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., p. 9

- Fenlon, Piazza San Marco, p. 59

- Torres, Il campanile di San Marco nuovamente in pericolo..., p. 8

- Fasoli, Le incursioni ungare..., pp. 96–100

- Kristó, Hungarian History in the Ninth Century, p. 198

- Parrot, The Genius of Venice, p. 30

- Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., p. 19.

- Norwich, A History of Venice, pp. 37–38

- Parrot, The Genius of Venice, pp. 30–31

- Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., p. 16

- Dorigo, Venezia romanica..., I, p. 24

- Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., p. 16

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 31

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., p. 11

- Torres, Il campanile di San Marco nuovamente in pericolo..., p. 23

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., pp. 4–5

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., pp. 12–13

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 7

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 8

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., p. 14

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 33–39

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 10

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 9–11

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., p. 17

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 13

- Sabellico, De situ urbis Venetae, c. c iiir

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., p. 21

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 9–17

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 18–20

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., p. 32

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 21–22

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., p. 22

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di San Marco in Venezia, pp. 23–25

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 32–34

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 61

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., p. 38

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 62

- Rosand, Myths of Venice..., p. 25

- Rosand, Myths of Venice..., pp. 32–36

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 25

- Sanudo, Diarii, XVI (1886), 6 July 1513

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 73–74

- Vitruvius, De architectura, 1.6.4

- Sansovino, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare..., fol. 106r

- Rosand, Myths of Venice..., pp. 12–16

- Rosand, Myths of Venice..., pp. 16–18

- Sanudo, Diarii, XVIII (1887), col. 246

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 63

- Morresi, Jacopo Sansovino, p. 216

- Morresi, Jacopo Sansovino, p. 213

- Morresi, Jacopo Sansovino, p. 215

- Morresi, Jacopo Sansovino, p. 219

- Lupo, 'Il restauro ottocentesco della Loggetta...', p. 132

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 26–27

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 37–38

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 44

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 27

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 38

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 39

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 30–31

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 42

- Block, Benjamin Franklin..., p. 91

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 31–32

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 74

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 77

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 96 and 98

- Whitehouse, Renaissance Genius..., p. 77

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 50

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 51–54

- Doglioni, Historia Venetiana, p. 87

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 135

- Sansovino and Stringa, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare..., 1604 edn, fol. 202v

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 141–144

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 61–64

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 128

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 194

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 195

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 188

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 51–54

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 191

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 175–178

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 196

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 197

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 198

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 199

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 200

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco di Venezia, pp. 54–55

- Sansovino, Le cose maravigliose et notabili della citta' di Venetia..., p. 161

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 191–192

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 55 and 57–58

- Doglioni, Historia Venetiana..., p. 89

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 264–266

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 266–270

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 271–275

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 291–299

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 35

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 36–38

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 39–40

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 41

- Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 121–123

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 41–43

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 44–45

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., p. 37

- Zanetto, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa"..., pp. 35–36

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 45

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 46

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 50

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 50–52

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 57

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 117–118

- "Stadtchronik 1902: Bemerkenswertes, Kurioses und Alltägliches" (in German), muenchen.de.

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 121–122

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 123

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 123–125

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., p. 100

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 126

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 64–65

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 65

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., pp. 94–95

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 127

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 67

- Fenlon, Piazza San Marco, p. 147

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, pp. 128–129

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., p. 110

- Marchesini, Un secolo all'ombra..., p. 120

- Gattinoni, Il campanile di san Marco in Venezia, p. 134

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., p. 36

- Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 70–71

- 'San Marco. Il consolidamento del campanile'..., p. 58

- 'San Marco. Il consolidamento del campanile'..., pp. 58–61

- 'Venezia, campanile San Marco 'guarito' con il titanio: Tolte transenne dopo 5 anni lavori per consolidare fondazioni', ANSA, 23 April 2013 [accessed 13 July 2020]

- 'La città e il turista', Comune di Dolo, [accessed 17 April 2021]

- 'Attrazioni culturali', Pirano, [accessed 17 April 2021]

- 'Il Duomo di S.Eufemia', Città d Rovigno, [accessed 17 April 2021]

- King, Anthony D., Spaces of Global Cultures: Architecture, Urbanism, Identity (London: Routledge, 2004), p. 214 ISBN 020348312X

- 'АТАКА КЛОНОВ: колокольня в усадьбе Богучарово', АРХИТЕКТУРНОЕ НАСЛЕДИЕ, 31 January 2008 [accessed 23 April 2013]

- Donnelly, Lu, H. David Brumble IV, and Franklin Toker, Buildings of Pennsylvania: Pittsburgh and Western Pennsylvania (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010), p. 315 ISBN 9780813928234

- 'Seattle Historical Sites, Summary for 301 S Jackson ST S', Seattle Department of Neighborhoods, [accessed 14 July 2020]

- Settis, Salvatore, If Venice Dies, trans. by André Naffis-Sahely (New York: New Vessel Press, 2014), p. 70

- 'Before This Seven-Day Wonder in Construction Is Completed It Will Be Overtopped by the Tall Tower of the Metropolitan Life', The New York Times, 29 December 1907, p. 5 [accessed 5 April 2020]

- Noel, Thomas Jacob, Guide to Colorado Historic Places: Sites Supported by the Colorado Historical Society's State Historical Fund (Englewood, CO: Westcliffe Publishers, 2007) p. 92

- 'Designation List 276, LP-1949: 14 Wall Street', New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, January 14, 1997, p. 3 [accessed 14 July 2020]

- Kiel City Hall: Facts and Sights (Kiel: Landeshauptstadt Kiel, July, 2018) [accessed 20 July 2020]

- Beagle, Jonathan M., Boston: A Visual History (Watertown, MA: Charlesbridge, 2013), p. 90

- Finacom, Steven, 'Berkeley's Campanile has a connection to Renaissance Venice', The Berkeley Daily Planet, 21 September 2002, p. 1 [accessed 15 July 2020]

- Brandbeer, Janice, 'Once Upon A City: Creating Toronto’s skyline', The Star, 24 March 2016 [accessed 15 July 2020]

- Bodil, Tennyson Smith, 'Tower of Remembrance', Restorica, Simon van der Stel Foundation, 24 (April 1989), 24–27

- Lau, Victoria, 'A Brief History Of The Oakland Tribune Tower', [accessed 4 February 2020]

- "Cercador Patrimoni Arquitèctonic: Torres d'Accés al Recinte de l'Exposició de 1929" (in Catalan). Barcelona city council. Archived from the original on 2013-07-24. Retrieved 2023-07-20.

- 'Historical Structures and Landscape Report: Jones Beach State Park' Archived 2019-12-30 at the Wayback Machine, New York State Office of Parks, Recreation & Historic Preservation, Division for Historic Preservation (2013), p. Water Tower 2 [accessed 15 July 2020]

- "Wigan Pier Quarter: Townscape Heritage Initiative" (PDF). p. 23. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

The Mill is protected by a fire sprinkler system which is fed from a large metal tank within the enclosure of the Mill's tower.

- Oswell, Paul (February 1, 2021). "The COVID-19 protocols at The Venetian Las Vegas allowed me to enjoy its stunning indoor canals and iconic architecture with peace of mind". Insider. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- "Venetian Macau: Asia's largest hotel". Business Today. 2012-03-21. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- DiCologero, Brittany (2020-12-09). "5 Facts About EPCOT's Italy Pavilion". WDW Magazine. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- "MCKINLEY HILL: Venice Grand Canal Mall Guide (Piazza, Gondola Ride, Shops, Restaurants and Cineplex)". Taguigeño. June 14, 2022. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

Notes

- The reference in the chronicle of John the Deacon to rivulus de Castello has led some historians to alternatively place the origin of the wall on the island of Olivolo. See Norwich, A History of Venice, pp. 37–38.

- The fourteenth-century map of Venice by Paolino da Venezia shows a wall only in the area of Saint Mark's Square. But the existence of the wall at that time is not supported in contemporary documents, and the map likely reflects a previous reality. See Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., pp. 14–15.

- Excavations in the early twentieth century revealed stone foundations between the bell tower and the Marciana Library which may have belonged to the early wall. See Dorigo, Venezia romanica..., I, p. 24.

- Medieval chronicles variously date the beginning of construction between 897 (Chronicon Venetum et Gradense) and 1150 (Agostini Chronicle, BNM ms It. VII, 1). The conflicting dates likely refer to different stages in construction or to the resumption of work after extended intervals. Most chronicles accept the tradition that the foundation was laid during the reign of Pietro Tribuno with a majority indicating the years 912 and 913. Gregorio Gattinoni accepts the tradition and suggests 912, considering it to be the last year of Tribuno's reign. See Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 24–29. There is, however, a discrepancy in that Tribuno's reign actually terminated in April/May 911 and was followed by an interregnum of eight months. See Claudio Rendina, I dogi: storia e segreti (Roma: Newton, 1984), p. 45. ISBN 9788854108172

- Excavations conducted in 1884 and the more detailed studies done after the collapse of the bell tower in 1902 revealed that the foundation of the bell tower consists in seven layers of varying qualities and construction techniques, an indication that the foundation was laid in different stages and over time. See Agazzi, Platea Sancti Marci..., p. 16

- Pietro Bon, consultant architect and buildings manager for the procurators of Saint Mark de supra is often confused with Bartolomeo Bon, chief consulting architect for the Salt Office. For relative documentation and the attribution of various projects, see Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 63–72 and Stefano Mariani, 'Vita e opere dei proti Bon Bartolomeo e Pietro' (unpublished doctoral thesis, Istituto Universitario di Architettura – Venezia, Dipartimento di Storia dell'Architettura, 1983)

- The legend of Venice's birth on 21 March 421 is traceable to at least the thirteenth-century chronicler Martino da Canal, Les estoires de Venise. It appears in the writings of Jacopo Dondi (Liber partium consilii magnifice comunitatis Padue, fourteenth century), Andrea Dandolo, Bernardo Giustiniani, Marin Sanudo, Marc'Antonio Sabellico, and Francesco Sansovino. See Muir, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice, pp. 70–71.

- Some modern lists give the sequence as Maleficio, Meza-terza, Trottiera, Nona, and Marangona. But the historical texts clearly indicate that the Meza-terza was larger than the Trottiera. See Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., pp. 147–148.

- Several sources provide information on the ringing of the bells of St Mark's, including Giovanni Nicolò Doglioni, Historia Venetiana scritta brevemente (Venetia: Damian Zenaro, 1598), pp. 87–91; Francesco Sansovino and Giovanni Stringa, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare... (Venetia: Altobello Salicato,1604), fols 202v–204r; Giuseppe Filosi, Narrazione Istorica Del Campanile Di San Marco In Venezia (Venezia: Gio. Battista Recurti), 1745, pp. 25–28; and the manuscript Giambattista Pace, Ceremoniale Magnum, sive raccolta universale di tutte le ceremonie spettanti alla Ducal Regia Capella di S. Marco, 1684. These sources, however, do not always agree. Gregorio Gattinoni argues that two sixteenth-century manuscripts, attributed to custodians of the bell tower, are more accurate. See Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre...,pp. 166–172.

- The original legislation of 29 May 1516 established sunset as the closing time of the ghetto. But in December 1516, the closing hour was moved to 2 hours after sunset in winter and 1 hour after sunset in summer. Although the charter of 1738 once again established sunset as the hour of closing, this was changed in 1760 to 4 hours after sunset in winter (October – March) and to 2 hours after sunset in summer (April – September). After 1788 the ghetto closed at midnight every day of the year. See Benjamin Ravid, Curfew Time in the Ghetto of Venice, in Ellen E. Kittell and Thomas F. Madden, ed., Medieval and Renaissance Venice (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1999), pp. 241–242

- Domestic heating was allowed for two hours after sunset, beginning on the first weekday of October. The period was extended to three hours after sunset, beginning on 18 October, and to four hours from 12 November. On the last Thursday of Carnival, the period was reduced to three hours and on 1 March to two hours. After Wednesday of Holy Week, domestic heat in the evening was not allowed. See Gattinoni, Historia di la magna torre..., p. 190.

- The original Maragona was tuned to A2. See Distefano, Centenario del campanile di san Marco..., pp. 77–78.

Bibliography

- Agazzi, Michela, Platea Sancti Marci: I luoghi marciani dall'XI al XIII secolo e la formazione della piazza (Venezia: Comune di Venezia, Assessorato agli affari istituzionali, Assessorato alla cultura and Università degli studi, Dipartimento di storia e critica delle arti, 1991) OCLC 889434590

- Block, Seymour Stanton Benjamin Franklin, Genius of Kites, Flights and Voting Rights (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2004) ISBN 9780786419425

- Distefano, Giovanni, Centenario del campanile di san Marco 1912–2012 (Venezia: Supernova, 2012) ISBN 9788896220573

- Doglioni, Giovanni Nicolò, Historia Venetiana scritta brevemente da Gio. Nicolo Doglioni, delle cose successe dalla prima fondation di Venetia sino all'anno di Christo 1597 (Venetia: Damian Zenaro, 1598)

- Dorigo, Wladimiro, Venezia romanica: la formazione della città medioevale fino all'età gotica, 2 vols (Venezia: Istituto veneto di scienze, lettere ed arti, 2003) ISBN 9788883142031

- Fasoli, Gina, Le incursioni ungare in Europa nel secolo X (Firenze: Sansoni, 1945) OCLC 797430902

- Fenlon, Iain, Piazza San Marco (London: Profile Books, 2010) ISBN 9781861978851

- Festa, Egidio, Galileo: la lotta per la scienza (Roma: GLF editori Laterza, 2007) ISBN 9788842083771

- Gattinoni, Gregorio, Il campanile di San Marco in Venezia (Venezia: Tip. libreria emiliana, 1912)

- Gattinoni, Gregorio, Historia di la magna torre dicta campaniel di San Marco (Vinegia: Zuanne Fabbris, 1910)

- Kristó, Gyula, Hungarian History in the Ninth Century (Szeged: Szegedi Középkorász Muhely, 1996)

- Lupo, Giorgio, 'Il restauro ottocentesco della Loggetta sansoviniana in Piazza San Marco a Venezia', ArcHistoR, n. 10, anno V (2018), 129–161

- Marchesini, Maurizia, Un secolo all'ombra, crollo e ricostruzione del Campanile di San Marco (Belluno: Momenti Aics, 2002) OCLC 956196093

- Morresi, Manuela, Jacopo Sansovino (Milano: Electa, 2000) ISBN 8843575716

- Muir, Edward, Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981) ISBN 0691102007

- Norwich, John Julius, A History of Venice (New York: Vintage Books, 1982) ISBN 9780679721970

- Parrot, Dial, The Genius of Venice: Piazza San Marco and the Making of the Republic (New York: Rizzoli, 2013) ISBN 9780847840533

- Rosand, David, Myths of Venice: the Figuration of a State (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001) ISBN 0807826413

- 'San Marco. Il consolidamento del campanile', Quaderni Trimestrali Consorzio Venezia Nuova, anno XIV, n. 1 (gennaio/marzo 2008), 55–62

- Sabellico, Marcantonio, De situ urbis Venetae. De praetoris officio. De viris illustribus (Venetia, Damiano da Gorgonzola, 1494)

- Sansovino, Francesco, Le cose maravigliose et notabili della citta' di Venetia. Riformate, accomodate, & grandemente ampliate da Leonico Goldioni (Venetia: Domenico Imberti, 1612)

- Sansovino, Francesco, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare descritta in 14 libri (Venetia: Iacomo Sansovino, 1581)

- Sansovino, Francesco and Giovanni Stringa, Venetia città nobilissima et singolare... (Venetia: Altobello Salicato,1604)

- Sanudo, Marin, Diari, ed. by G. Berchet, N. Barozzi, and M. Allegri, 58 vols (Venezia: Berchet, N. Barozzi, and M. Allegri, 1879–1903)

- Torres, Duilio, Il campanile di San Marco nuovamente in pericolo?: squarcio di storia vissuta di Venezia degli ultimi cinquant'anni (Venezia: Lombroso, 1953)

- Whitehouse, David, Renaissance Genius: Galileo Galilei & His Legacy to Modern Science (New York: Sterling Publishing, 2009) ISBN 9781402769771

- Zanetto, Marco, Il cambio d'abito del "Paron de casa": da torre medievale a campanile rinascimentale (Venezia: Società Duri i banchi, 2012)

External links

Media related to Campanile of St. Mark's Basilica (Venice) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Campanile of St. Mark's Basilica (Venice) at Wikimedia Commons

_Torres_venecianes_-_El_Tibidabo_-_Temple_Expiatori_del_Sagrat_Cor.jpg.webp)