Tower of the Winds

The Tower of the Winds, also known by other names, is an octagonal Pentelic marble tower in the Roman Agora in Athens, named after the eight large reliefs of wind gods around its top. Its date is contested, but was by about 50 BC at the latest; it was mentioned by Varro in his De re Rustica of about 37 BC.[1] It is "one of the very small number of buildings from classical antiquity that still stands virtually intact", as it has been continuously occupied for a series of different functions.[2]

Formerly topped by a wind vane, it is the only surviving horologium or clock tower from classical antiquity.[3] It was built to house a large water clock and incorporated sundials placed prominently on its face to function as a kind of early clocktower.

According to A. W. Lawrence, "the originality of this building is exceptional, and of a character out of keeping with Hellenistic architecture as we know it ... the design is obviously Greek, both in the severity of decorative treatment and in the antiquated method of roofing. The contrast with work of the Roman Empire is extraordinary, considering the date", which is long after the Roman conquest of Greece.[4]

Names

The English name Tower of the Winds—personified on the building as the Anemoi—is ultimately a calque of the ancient Greek name Pýrgos tōn Anémōn (Πύργος των Ανέμων). It has also been known as the Horologium (Latin) or Horologion (Greek: Ὡρολόγιον, Hōrológion), from hṓra (ὥρα, "time period, hour") lógos (λόγος, "writing, recording") + -ion (-ιον), together usually meaning a sundial, clepsydra, or other timekeeping device but here used to describe the location housing them.

It is now known in Greek as the "Winds" (Greek: Αέρηδες, Aérides) and as the "Clock of Cyrrestes" (Greek: Ωρολόγιο του Κυρρήστου, Orológio tou Kyrrístou).

Design

Raised on three steps, the Tower of the Winds is 12 metres (39 ft) tall and has a diameter of about 8 metres (26 ft). In antiquity it was topped by a bronze statue of a Triton, holding a rod that acted as a weather vane indicating the wind direction.[5][6] Below the frieze depicting the eight wind deities—Boreas (N), Kaikias (NE), Apeliotes (E), Eurus (SE), Notus (S), Livas (SW), Zephyrus (W), and Skiron (NW)—there are eight sundials.[7] A cornice above is decorated with lions' heads in relief, functioning as water spouts.

Inside, there is a single large room. From ancient mentions by Varro and Vitruvius, it seems that time was measured by a water clock, driven by water coming down from the Acropolis. There are holes and channels in the floor relating to this, but the mechanism, presumably of metal and wood, has gone. Research has shown that the considerable height of the tower was motivated by the intention to place the sundials and the wind-vane at a height visible from the Agora, effectively making it an early example of a clocktower.[8]

.jpg.webp)

It had two porches with pediments, supported by two Corinthian columns at the front, now disassembled, though the lower parts of three columns remain in place. These columns had capitals of a design now sometimes known as "Tower of the Winds Corinthian", a "late variant form" lacking the volutes ordinarily found in Corinthian capitals. There is a single row of acanthus leaves at the bottom of the capital, with a row of "tall, narrow leaves" behind.[9] These cling tightly to the swelling shaft, and are sometimes described as "lotus" leaves, as well as the vague "water-leaves"; their similarity to leaf forms on many ancient Egyptian capitals has been remarked on.[10]

To the rear a "turret" held the water for the clock. The main roof is essentially original, with 24 triangular stone slabs, carved on the outside to look like tiles;[11] here rows of modern standard rounded roof tiles now cover the joins. Inside eight very small columns, less than four feet high but with richly carved shafts, stand at each corner of the octagon, on a circular cornice, running up to a circular architrave.[12]

Functionality

Andronicus of Cyrrhus, the designer, seems to have written a book on the winds. A passage in Vitruvius's chapter on town planning in his On Architecture (De architectura) seems to be based on this missing book. The emphasis is on planning street orientations to maximize the benefits, and minimize the harms, from the various winds.[13] The London Vitruvius, the oldest surviving manuscript, includes only one of the original illustrations, a rather crudely drawn octagonal wind rose in the margin. This was written in Germany in about 800 to 825, probably at the abbey of Saint Pantaleon, Cologne.[14]

The large reliefs characterize each wind in terms of the things they carry, and often spill out from containers, the warmth of their clothing, and to some extent their physiques and expressions.

History

According to Vitruvius and Varro, the astronomer Andronicus of Cyrrhus designed the Tower of the Winds.[15] But very little is known about his life, not even whether he came from the Cyrrhus in Macedonia or the larger Selucid city (named after it) on the Euphrates.[16] From the style of the sculptures the tower is usually dated around 50 BC, not long before Varro and Vitruvius mention it. An alternative possibility is that it was part of the generosity of Attalus III of Pergamon (d. 131 BC) who built the Stoa of Attalus in the city. This would place it earlier than the rest of the Roman forum.[17]

If the usual dating is correct, it formed part of the reconstruction of Athens after it was mostly levelled by the Roman legions under Sulla in 86 BC following the Siege of Athens and Piraeus during the First Mithridatic War.[18]

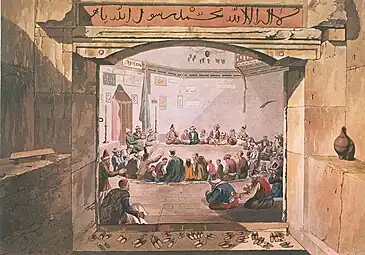

In early Christian times, the building was used as the bell-tower of an Eastern Orthodox church. At Ottoman rule time it was buried up to half its height, and traces of this can be observed in the interior, where Turkish inscriptions may be found on the walls. It was fully excavated in the 19th century by the Archaeological Society of Athens. The thesis that there was an Athens Mevlevi Convent or its ritual hall in the Tower and that the other buildings belonging to the Convent were located around it is an unsubstantiated claim and fabrication. The Tower, which was converted into a Qadirî tekke sometime between 1749 and 1751, was used by Qadirî dervishes to perform their religious rituals for 70 years between 1751 and 1821, and was evacuated after the Greek revolt of 1821.[19]

The building became better known outside Greece from 1762, when a description and several careful measured engraved illustrations were published in London in the first volume of The Antiquities of Athens. The tower was one of only five ancient Greek buildings given a full treatment in this important work. It had been surveyed by James "Athenian" Stuart and Nicholas Revett on an expedition in 1751–54.

By this point depictions and early photographs show that the surrounding ground level had risen by several feet, and entry was by a sort of trench around part of the building. In the later 19th and 20th centuries the surrounding area was cleared of modern buildings and excavated, restoring the original ground level around most of the building.

The Athens Ephorate of Antiquities performed restoration work, cleaning and conserving the structure, between 2014 and 2016.[20]

Plan - Stuart & Revett, 1762

Plan - Stuart & Revett, 1762 Inside: Roof of tower

Inside: Roof of tower Inside: Floor of tower showing holes for mechanism

Inside: Floor of tower showing holes for mechanism General view of the tower, from Stuart & Revett's The Antiquities of Athens, illustration drawn in 1751, with added hand-colouring

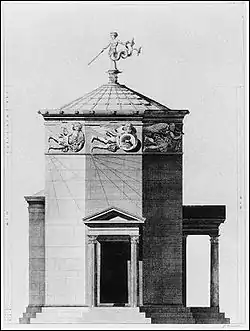

General view of the tower, from Stuart & Revett's The Antiquities of Athens, illustration drawn in 1751, with added hand-colouring 18th-century reconstruction of the Tower of the Winds from The Antiquities of Athens

18th-century reconstruction of the Tower of the Winds from The Antiquities of Athens Turkish Kadiri dervishes perform their religious rituals in the building in April 1805.

Turkish Kadiri dervishes perform their religious rituals in the building in April 1805.

Legacy

Several buildings are based, often very loosely, on the design of the Towers of the Winds, including:

- The 18th-century Tower of the Winds on top of the Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford, England,

- The Temple of the Winds, which stands in the grounds of Mount Stewart near Newtownards in Northern Ireland, designed by James "Athenian" Stuart who had studied and published the original.[21]

- St Pancras Church (1822) designed by William Inwood and his son Henry William Inwood, located in Euston, London. This is a unique Greek-revival church, that features two sets of Caryatids and a tower that was based on the classical Tower of the Winds.

- The Daniel S. Schanck Observatory (1865) an early astronomical observatory at Rutgers University in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

- The mausoleum of the founder of the Greek National Library Panayis Vagliano at West Norwood Cemetery, London.

- The 15th-century Torre del Marzocco in Livorno.

- The tower on St Luke's Church, West Norwood, in London, designed by Francis Octavius Bedford after he visited Athens on a Society of Dilettanti scholarship circa 1810.

- A similar tower in Sevastopol, built in 1849.

.jpg.webp)

- The Carnaby Temple near Carnaby, East Riding of Yorkshire, built in 1770.

- The Maitland Robinson building in Downing College, Cambridge, designed by Quinlan Terry in 1992.

- The "Storm Tower" in Bude, Cornwall (1835), by George Wightwick

- The chapel of the Flanders Field American Cemetery built in 1930 in Waregem, Belgium, by Paul Cret.[22]

- The "Four Winds" brick chimney of the former hydraulic power station beside Glasgow Harbour at Prince's Dock, Glasgow, designed by Burnet, Son and Campbell and built in 1894 for the Clyde Navigation Trust.

References

Citations

- Wallace-Hadrill, 46

- Noble & de Solla Price 1968, p. 345.

- Lawrence, 237

- Lawrence, 237

- Noble & de Solla Price 1968, pp. 353 & 345.

- Lawrence, 237

- Noble & de Solla Price 1968, p. 353.

- Noble & de Solla Price 1968, pp. 345 & 349.

- Lawrence, 237

- Fergusson, James, The Illustrated Handbook of Architecture, Vol 2, p. 273, 1855, John Murray, google books

- Lawrence, 237

- Lawrence, 237

- Wallace-Hadrill, 46-47

- Detailed record for Harley 2767, British Library; the diagram is figure 3:1 in Wallace-Hadrill, p. 47

- Noble & de Solla Price 1968, p. 354.

- Lawrence, 237 and Watkin, 39 plump for the eastern option

- Wallace-Hadrill, 46

- Tung, Anthony (2001). Preserving the World's Great Cities: The Destruction and Renewal of the Historic Metropolis. New York: Three Rivers Press. pp. 256–260. ISBN 0-609-80815-X.

- Tagaris, Karolina; Fronista, Phoebe. "Ancient Greece's restored tower of winds keeps its secrets". Kathimerini. Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- "Mount Stewart". UK: National Trust. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- Grossman, Elizabeth Greenwell (1996). The Civic Architecture of Paul Cret. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 9780521496018.

Sources

- Lawrence, A. W., Greek Architecture, 1957, Penguin, Pelican history of art

- Noble, Joseph V.; de Solla Price, Derek J. (1968). "The Water Clock in the Tower of the Winds". American Journal of Archaeology. 72 (4): 345–355. doi:10.2307/503828. ISSN 0002-9114. JSTOR 503828. S2CID 193112893 – via JSTOR.

- Wallace-Hadrill, Andrew in Rome and the Colonial City: Rethinking the Grid, 2022, eds. Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, Sofia Greaves, Oxbow Books, ISBN 9781789257823, google books

Further reading

- Beresford, James (2015). "A Monument to the Winds". Navigation News. London: Royal Institute of Navigation. pp. 17–19. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- Webb, Pamela A. (2017). "The Tower of the Winds in Athens: Greeks, Romans, Christians, and Muslims; Two Millennia of Continual Use". Memoirs of the American Philosophical Society. Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society Press. 270.

- Duru, Dr. Riza (2021). “The Tower of Winds was neither the Mevlevi Convent of Athens nor Its Ritual Hall”. https://www.academia.edu/45679939.

External links

- 16 minute video History Victorum

- Tower of the Winds and characters sculpted on it