Cardiac myxoma

A myxoma is a rare benign tumor of the heart. Myxomata are the most common primary cardiac tumor in adults, and are most commonly found within the left atrium near the valve of the fossa ovalis. Myxomata may also develop in the other heart chambers.[1] The tumor is derived from multipotent mesenchymal cells.[1] Cardiac myxoma can affect adults between 30 and 60 years of age.[2]

| Atrial myxoma | |

|---|---|

| |

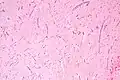

| Micrograph of an atrial myxoma. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Cardiology |

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms may occur at any time, but most often they accompany a change of body position. Pedunculated myxomata can have a "wrecking ball effect", as they lead to stasis and may eventually embolize themselves. Symptoms may include:[3]

- Shortness of breath with activity

- Platypnea – Difficulty breathing in the upright position with relief in the supine position

- Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea – Breathing difficulty when asleep

- Dizziness

- Fainting

- Palpitations – Sensation of feeling your heart beat

- Chest pain or tightness

- Sudden Death (In which case the disease is an autopsy finding)

The symptoms and signs of left atrial myxomata often mimic mitral stenosis. General symptoms may also be present, such as:[3]

- Cough

- Pulmonary edema – as blood backs up into the pulmonary artery, after increased pressures in the left atrium and atrial dilation

- Hemoptysis

- Fever

- Cachexia – Involuntary weight loss

- General discomfort (malaise)

- Joint pain

- Blue discoloration of the skin, especially the fingers change color upon pressure, cold, or stress (Raynaud's phenomenon)

- Clubbing – Curvature of nails accompanied with soft tissue enlargement of the fingers

- Swelling – any part of the body

- Presystolic heart murmur[4]

These general symptoms may also mimic those of infective endocarditis.

Complications

- Arrhythmias

- Pulmonary edema

- Peripheral emboli

- Spread (metastasis) of the tumor

- Blockage of the mitral heart valve

- Stroke

- Fusiform cerebral aneurysms

Causes

Myxomata are the most common type of adult primary heart tumor.[1][5] Most myxomata arise sporadically (90%), and only about 10% are thought to arise due to inheritance.[6]

About 10% of myxomata are inherited, as in Carney syndrome. Such tumors are called familial myxomata. They tend to occur in more than one part of the heart at a time, and often cause symptoms at a younger age than other myxomata. Other abnormalities are observed in people with Carney syndrome include skin myxomata, pigmentation, endocrine hyperactivity, schwannomas and epithelioid blue nevi.[1] Myxomata are more common in women than men.[1][3]

Diagnosis

A doctor will listen to the heart with a stethoscope. A "tumor plop" (a sound related to movement of the tumor), abnormal heart sounds, or a murmur similar to the mid-diastolic rumble of mitral stenosis may be heard. These sounds may change when the patient changes position.[7]

Right atrial myxomata rarely produce symptoms until they have grown to be at least 13 cm (about 5 inches) wide.

Tests may include:[8]

- Echocardiogram and Doppler study

- Chest x-ray

- CT scan of chest

- Heart MRI

- Left heart angiography

- Right heart angiography

- ECG—may show atrial fibrillation

Blood tests:

- Blood tests: An FBC may show anemia and increased WBCs (white blood cells). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is usually increased.

- Blood tests: An FBC may show anemia and increased WBCs (white blood cells). The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is usually increased.

Echocardiogram of atrial myxoma

Echocardiogram of atrial myxoma- Echocardiogram showing atrial myxoma[9]

Echocardiogram showing atrial myxoma[9]

Echocardiogram showing atrial myxoma[9]

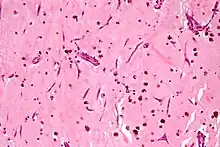

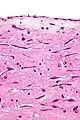

Atrial myxoma and myocardium. H&E stain.

Atrial myxoma and myocardium. H&E stain. Atrial myxoma. H&E stain.

Atrial myxoma. H&E stain. Atrial myxoma. H&E stain.

Atrial myxoma. H&E stain. Atrial myxoma covered by endothelium. H&E stain.

Atrial myxoma covered by endothelium. H&E stain.

Treatment

The surgery is treatment of choice,[10] tumor must be surgically removed. Some patients will also need their mitral valve replaced. This can be done during the same surgery. Usually, inadequate excision of the tumor, development from a secondary focus, or intracardiac implantation from the primary tumor are the attributable explanation for recurrence,[11] and it is more likely to occur in the first 10 postoperative years, especially in younger patients.[12]

Prognosis

Although a myxoma is not malignant with risk of metastasis,[3] complications are common. Untreated, a myxoma can lead to an embolism (tumor cells breaking off and traveling with the bloodstream). Myxoma fragments can move to the brain, eye, or limbs.

If the tumor continues to enlarge inside the heart, it can block blood flow through the mitral valve and cause symptoms of mitral stenosis or mitral regurgitation. This may require emergency surgery to prevent sudden death.[13]

References

- Hecht, Sisalee M. (2009-10-27). "A Review of: "Current Diagnosis & Treatment: Cardiology. 3rd ed. Crawford, Michael H., ed."". Medical Reference Services Quarterly. 28 (4): 401–402. doi:10.1080/02763860903249993. ISSN 0276-3869. S2CID 73897596.

- Velez Torres, Jaylou M.; Martinez Duarte, Ernesto; Diaz-Perez, Julio A.; Rosenberg, Andrew E. (November 2020). "Cardiac Myxoma: Review and Update of Contemporary Immunohistochemical Markers and Molecular Pathology". Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 27 (6): 380–384. doi:10.1097/PAP.0000000000000275. ISSN 1072-4109. PMID 32732585. S2CID 220892586.

- Aiello, Vera Demarchi; Campos, Fernando Peixoto Ferraz de (2016). "Cardiac Myxoma". Autopsy & Case Reports. 6 (2): 5–7. doi:10.4322/acr.2016.030. ISSN 2236-1960. PMC 4982778. PMID 27547737.

- Eric J. Topol. The Topol Solution: Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine, Third Edition with DVD, Plus Integrated Content Website, Volume 355. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Oct 19, 2006; page 223. ISBN 0781770122

- Vaideeswar, P.; Butany, JW. (Feb 2008). "Benign cardiac tumors of the pluripotent mesenchyme". Semin Diagn Pathol. 25 (1): 20–8. doi:10.1053/j.semdp.2007.10.005. PMID 18350919.

- Masters, Barry R. (2012-05-25). "Harrisons's Principles of Internal Medicine, 18th Edition, two volumes and DVD. Eds: Dan L. Longo, Anthony S. Fauci, Dennis L. Kasper, Stephen L. Hauser, J. Larry Jameson and Joseph Loscalzo, ISBN 9780071748896 McGraw Hill". Graefe's Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology. 250 (9): 1407–1408. doi:10.1007/s00417-012-1940-9. ISSN 0721-832X. S2CID 11647732.

- "Cardiac Myxoma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- "Cardiac Myxoma". The Lecturio Medical Concept Library. Retrieved 6 July 2021.

- "UOTW #31 - Ultrasound of the Week". Ultrasound of the Week. 30 December 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2017.

- Lone, R. A.; Ahanger, A. G.; Singh, S.; Mehmood, W.; Shah, S.; Lone, G.; Dar, A.; Bhat, M.; Sharma, M.; Lateef, W. (2008). "Atrial myxoma: Trends in management". International Journal of Health Sciences. 2 (2): 141–151. PMC 3068734. PMID 21475496.

- Sheng, W. B.; Luo, B. E.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zou, L. J.; Xu, Z. Y.; Zhang, H. Y.; Ji, G. Y. (2012). "Risk factors for postoperative recurrence of cardiac myxoma and the clinical managements: A report of 5 cases in one center and review of literature". Chinese Medical Journal. 125 (16): 2914–2918. PMID 22932090.

- Shah, I. K.; Dearani, J. A.; Daly, R. C.; Suri, R. M.; Park, S. J.; Joyce, L. D.; Li, Z.; Schaff, H. V. (2015). "Cardiac Myxomas: A 50-Year Experience with Resection and Analysis of Risk Factors for Recurrence". The Annals of Thoracic Surgery. 100 (2): 495–500. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2015.03.007. PMID 26070596.

- "A Biatrial Myxoma with Triple Ripples".