Cardwellia

Cardwellia is a monotypic genus in the plant family Proteaceae. The sole described species is Cardwellia sublimis − commonly known as northern silky oak, bull oak or lacewood − which is endemic to the rainforests of northeastern Queensland, Australia.

| Northern silky oak | |

|---|---|

| |

| In flower | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Order: | Proteales |

| Family: | Proteaceae |

| Subfamily: | Grevilleoideae |

| Tribe: | Macadamieae |

| Subtribe: | Gevuininae |

| Genus: | Cardwellia F.Muell.[3] |

| Species: | C. sublimis |

| Binomial name | |

| Cardwellia sublimis F.Muell.[4] | |

Description

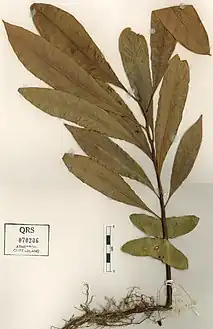

Cardwellia sublimis is a large tree reaching up to 40 m (130 ft) in height and a diameter of 2 m (6 ft 7 in), often becoming an emergent standing well above the canopy.[5][6] The bark is thin and there is usually no buttressing.[6][7] The leaves are alternate, dark green above with a silvery brown sheen below.[5][7][8] On seedlings the leaves are simple but on mature trees they are pinnately compound,[5] and there is a graduation of the leaf morphology as the tree grows (see gallery). Leaves on mature trees reach up to 65 cm (26 in) long with a petiole up to 11 cm (4.3 in) long[5] They have 3 to 10 pairs of oval to oblong leaflets, each of which is 9–18 cm (3.5–7.1 in) long and 4–7 cm (1.6–2.8 in) wide.[5][7][8]

The inflorescence is a raceme up to 16 cm (6.3 in) long,[5][8][9] with sessile flowers in pairs carried on a short peduncle.[7] They are produced above the tree canopy, and prolific − the canopy can be covered with the cream-white flowerheads in late spring and summer.[5][7]

The fruit are large, ellipsoidal, woody, dehiscent follicles about 8–11 cm (3.1–4.3 in) long and 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in) wide, carried on vertical peduncles and displayed above the canopy, creating a distinctive feature of this species.[5][7][8][10] They split along one side to release the seeds,[10] and will persist for some time both on the tree and on the ground after they have fallen.[7] They contain up to 14 winged seeds measuring about 7 by 3 cm (2.8 by 1.2 in).[5][7][8]

Taxonomy and naming

The Victorian colonial botanist Ferdinand von Mueller first described this species in 1865 based on material collected by John Dallachy in Rockingham Bay. It was published in his work Fragmenta Phytographiae Australiae[4][7][9]

Phylogeny

Molecular analysis indicates Cardwellia sublimis is a member of the subtribe Gevuininae,[11] and is the earliest offshoot from the main ancestor of the other genera. It is thought to have separated around 35 million years ago in the late Eocene.[12]

Etymology

Mueller created the genus name in honour of Edward Cardwell, who was Secretary of State for the Colonies from 1864 to 1866. The species name that he chose is the Latin adjective sublimis, with the meanings uplifted, high, lofty, exalted, or sublime − it may possibly be a reference to the fruit (which is held above the tree's canopy) or to the height of the tree itself.[10][13]

Common names

The name for this tree in the Dyirbal language is jungan. The more general word gurruŋun is used in their taboo vocabulary, and is also applied to Darlingia ferruginea and Helicia australasica.[14] In the English language, the common names "bull oak" and "northern silky oak" arose in colonial times and are references to the similarity of the grain of its timber to that of the oaks of England and Europe that were more familiar to the colonists.[15]

Distribution and habitat

Cardwellia sublimis is endemic to a small part of northeastern Queensland, occurring from the area around Rossville south to the Paluma Range National Park, and from the coastal flats to the adjacent ranges and tablelands. It grows in rainforest on a variety of soil types, and at altitudes from sea level to around 1,300 m (4,300 ft).[5][7][10][13]

Ecology

Ants (Formicidae) are known to create wounds on the trunk of the northern silky oak by biting it, in order to access and consume the sugary sap.[16] The seeds are eaten by sulphur-crested cockatoos (Cacatua galerita) and native rats.[13]

Conservation

The northern silky oak has been assessed as least concern by both the Queensland Department of Environment and Science and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).[1][2] The IUCN states in its assessment summary that the "species was heavy logged in the past but this has stopped. Currently, the species has no immediate threats".[2]

Uses and cultivation

Cardwellia sublimis was harvested extensively in the past for its highly-regarded timber,[2] which was widely used in houses of the traditional "Queenslander" style, especially for windows. It was also commonly used for furniture, joinery and flooring.[6][7] In limited supply today, it is now used mostly for cabinet work and veneers[5]

Attempts to grow Cardwellia sublimis in plantations have not been very successful,[7] however it has good potential as a park and street tree due to its large size, attractive foliage and showy flowering displays. It is readily propagated from seed (although seed must be fresh, stored for less than 6 weeks)[17] and has been grown successfully in Melbourne.[18]

Gallery

Seedling, with simple leaves and cotyledons still attached

Seedling, with simple leaves and cotyledons still attached Sapling leaf, showing the intermediate pinnatisect morphology

Sapling leaf, showing the intermediate pinnatisect morphology Mature pinnate leaves

Mature pinnate leaves Underside of leaves

Underside of leaves

Inflorescences

Inflorescences Inflorescences

Inflorescences Mature fruit, some with seeds still enclosed

Mature fruit, some with seeds still enclosed A dehisced fruit found on the ground

A dehisced fruit found on the ground

References

- "Species profile—Cardwellia sublimis". Queensland Department of Environment and Science. Queensland Government. 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Forster, P., Ford, A., Griffith, S. & Benwell, A. (2020). "Cardwellia sublimis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T61956837A61956839. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-2.RLTS.T61956837A61956839.en. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Cardwellia". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI). Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- "Cardwellia sublimis". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI). Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Hyland, B.P.M. (2020). "Cardwellia sublimis". Flora of Australia. Australian Biological Resources Study, Department of Climate Change, the Environment and Water: Canberra. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- "Northern silky oak". Business Queensland. Queensland Government. 12 December 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- F.A. Zich; B.P.M Hyland; T. Whiffen; R.A. Kerrigan (2020). "Cardwellia sublimis". Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants, Edition 8. Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- "Cardwellia sublimis". Discover Nature at JCU. James Cook University. 2 February 2022. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- Mueller, Ferdinand von (1865). Fragmenta phytographiæ Australiæ. Vol. 5. Melbourne: Joannis Ferres. p. 24. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- "Rainforest Tree of the Month, March 2020 – Cardwellia sublimis". Paluma – our village in the mist. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- Weston, Peter H.; Barker, Nigel P. (2006). "A new suprageneric classification of the Proteaceae, with an annotated checklist of genera". Telopea. 11 (3): 314–344. doi:10.7751/telopea20065733.

- Mast, Austin R.; Willis, Crystal L.; Jones, Eric H.; Downs, Katherine M.; Weston, Peter H. (July 2008). "A smaller Macadamia from a more vagile tribe: inference of phylogenetic relationships, divergence times, and diaspore evolution in Macadamia and relatives (tribe Macadamieae; Proteaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 95 (7): 843–870. doi:10.3732/ajb.0700006. ISSN 1537-2197. PMID 21632410. Archived from the original on 1 September 2020. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- Cooper, Wendy; Cooper, William T. (June 2004). Fruits of the Australian Tropical Rainforest. Clifton Hill, Victoria, Australia: Nokomis Editions. p. 408. ISBN 9780958174213.

- Dixon, Robert Malcolm Ward (1990). "The Origin of "Mother-in-Law Vocabulary" in Two Australian Languages". Anthropological Linguistics. 32 (1/2): 1−56. JSTOR 30028138.

- "Cardwellia sublimis – Northern Silky Oak/Bull Oak". Wild Wings & Swampy Things. 7 April 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2023.

- Blüthgen, Nico; Gottsburger, Gerhard; Fiedler, Konrad (August 2004). "Sugar and amino acid composition of ant-attended nectar and honeydew sources from an Australian rainforest". Austral Ecology. 29 (4): 418–429. doi:10.1111/j.1442-9993.2004.01380.x. Retrieved 18 March 2023.

- Sanderson, K.D. (February 1998). "Effect of storage conditions on viability of wind-dispersed seeds of some cabinet timber species from Australian tropical rainforests". Australian Forestry. 61 (2): 76–81. doi:10.1080/00049158.1998.10674723. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- Wrigley, John; Fagg, Murray (1991). Banksias, Waratahs and Grevilleas. Sydney: Angus & Robertson. pp. 126–27. ISBN 0-207-17277-3.

External links

Data related to Cardwellia sublimis at Wikispecies

Data related to Cardwellia sublimis at Wikispecies Media related to Cardwellia sublimis at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cardwellia sublimis at Wikimedia Commons- View a map of historical sightings of this species at the Australasian Virtual Herbarium

- View observations of this species on iNaturalist

- View images of this species on Flickriver