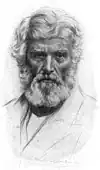

Thomas Carlyle's prose style

Thomas Carlyle believed that his time required a new approach to writing:

But finally do you reckon this really a time for Purism of Style; or that Style (mere dictionary style) has much to do with the worth or unworth of a Book? I do not: with whole ragged battallions of Scott's-Novel Scotch, with Irish, German, French and even Newspaper Cockney (when "Literature" is little other than a Newspaper) storming in on us, and the whole structure of our Johnsonian English breaking up from its foundations,—revolution there as visible as anywhere else![1]

Carlyle's style lends itself to several nouns, the earliest being Carlylism from 1841. The Oxford English Dictionary records Carlylese, the most commonly used of these terms, as having first appeared in 1858.[2] Carlylese makes characteristic use of certain literary, rhetorical and grammatical devices, including apostrophe, apposition, archaism, exclamation, imperative mood, inversion, parallelism, portmanteau, present tense, neologisms, metaphor, personification, and repetition.[3][4]

Carlylese

At the beginning of his literary career, Carlyle worked to develop his own style, cultivating one of intense energy and visualisation, characterised not by "balance, gravity, and composure" but "imbalance, excess, and excitement."[5] Even in his early anonymous periodical essays his writing distinguished him from his contemporaries. Carlyle's writing in Sartor Resartus is described as "a distinctive mixture of exuberant poetic rhapsody, Germanic speculation, and biblical exhortation, which Carlyle used to celebrate the mystery of everyday existence and to depict a universe suffused with creative energy."[6]

Carlyle's approach to historical writing was inspired by a quality that he found in the works of Goethe, Bunyan and Shakespeare: "Everything has form, everything has visual existence; the poet's imagination bodies forth the forms of things unseen, his pen turns them to shape."[7] He rebuked typical, Dryasdust historiography: "Dull Pedantry, conceited idle Dilettantism,—prurient Stupidity in what shape soever,—is darkness and not light!"[8] Rather than reporting events in a detached, distanced manner, he presents immediate, tangible occurrences, often in the present tense.[9] In his French Revolution, "the great prose epic of the nineteenth century", Carlyle managed to craft an overwhelmingly original voice, producing deliberate tension by combining the common language of the time with self-conscious allusions to traditional epics, Homer, Shakespeare, Milton, or some contemporary French history source in nearly every sentence of its three volumes.[6]

Carlyle's social criticism directs his penchant for metaphor toward the Condition-of-England question, depicting a thoroughly diseased society. Declaiming the aimlessness and infirmity of English leadership, Carlyle made use of satirical characters like Sir Jabesh Windbag and Bobus of Houndsditch in Past and Present. Memorable catchphrases such as Morrison's Pill, the Gospel of Mammonism, and "Doing as One Likes" were employed to counteract empty platitudes of the day. Carlyle transformed his depicted reality in various ways, whether by conversion of actual human beings into grotesque caricatures, envisioning isolated facts as emblems of morality, or by manifestation of the supernatural; in Latter-Day Pamphlets, pampered felons appear in nightmarish visions and wrongheaded philanthropists wallow in their own filth.[10]

Carlyle could at once use imaginative powers of rhetoric and vision to "render the familiar unfamiliar". He could also be a sharp-eyed, keen observer of the actual, reproducing scenes with imagistic clarity, as he does in the Reminiscences, the Life of John Sterling and the letters; he has often been called the Victorian Rembrandt.[11][12][13] As Mark Cumming explains, "Carlyle's intense appreciation of visual existence and of the innate energy of object, coupled with his insistent awareness of language and his daunting verbal resources, formed the immediate and lasting appeal of his style."[10]

Coinages

| Type | Number | Author rank |

|---|---|---|

| Total quotations[lower-alpha 1] | 6778 | 26th |

| First quotations[lower-alpha 2] | 547 | 45th |

| First quotations in a special sense[lower-alpha 3] | 1789 | 33rd |

The present table represents data gathered from Oxford English Dictionary Online, 2012. An explanatory footnote is provided for each "Type".

Over fifty percent of these entries come from Sartor Resartus, French Revolution, and History of Frederick the Great. Of the 547 First Quotations cited by the O.E.D., 87 or 16% are listed as being "in common use today."[14]

Humour

Carlyle's sense of humour and use of humorous characters was shaped by early readings of Cervantes, Samuel Butler, Jonathan Swift, and Laurence Sterne. He initially attempted a fashionable irony in his writing, which he soon abandoned in favour of a "deeper spirit" of humour. In his essays on Jean Paul, Carlyle rejects the dismissive, ironic humour of Voltaire and Molière, embracing the warm and sympathetic approach of Jean Paul and Cervantes. Carlyle establishes humour in many of his works through his use of characters, such as the Editor (in Sartor Resartus), Diogenes Teufelsdröckh (lit. 'God-born Devil's-dung'), Gottfried Sauerteig, Dryasdust, and Smelfungus. Linguistically, Carlyle explores the humorous possibilities of his subject through exaggerated and dazzling wordplay, "in sentences abounding with rhetorical devices: emphasis by capitalization, punctuation marks, and italics; allegory, symbol, and other poetic devices; hyphenated words, Germanic translations and etymologies; quotations, self-quotations, and bizarre allusions; and repetitious and antiquated speech."[15]

Allusion

Carlyle's writing is highly allusive. Ruth apRoberts writes that "Thomas Carlyle may well be, of all writers in English, the most thoroughly imbued with the Bible. His language, his imagery, his syntax, his stance, his worldview—are all affected by it."[16] Job, Ecclesiastes, Psalms and Proverbs are Carlyle's most frequently referenced books of the Old Testament, and Matthew that of the New Testament.[17] The structure of Sartor uses a basic typological Biblical pattern.[18] The French Revolution is filled with dozens of Homeric allusions, quotations, and a liberal use of epithets drawn from Homer as well as Homeric epithets of Carlyle's own devising.[19] The influence of Homer, particularly his attention to detail, his strongly visual imagination, and his appreciation of language, is also seen in Past and Present and Frederick the Great.[20] The language and imagery of John Milton is present throughout Carlyle's writings. His letters are full of allusions to a wide range of Milton's texts, including Lycidas, L'Allegro, Il Penseroso, Comus, Samson Agonistes and, most frequently, Paradise Lost.[21] Carlyle's works abound with direct and indirect references to William Shakespeare. The French Revolution contains two dozen allusions to Hamlet alone, and dozens more to Macbeth, Othello, Julius Caesar, King Lear, Romeo and Juliet, the histories, and the comedies.[22]

Reception

The earliest literary criticism on Carlyle is an 1835 letter from Sterling, who complained of the "positively barbarous" use of words in Sartor, such as "environment," "stertorous," and "visualised," words "without any authority" that are now widely used.[23] William Makepeace Thackeray recorded his mixed response in his 1837 review of French Revolution, decrying its "Germanisms and Latinisms" while acknowledging that "with perseverance, understanding follows, and things perceived first as faults are seen to be part of his originality, and powerful innovations in English prose."[24]

In the opinion of James Russell Lowell, Carlyle possessed "a mastery of language equalled only by the greatest poets".[25] Anthony Trollope called Carlyle "our dear old English Homer—Homer in prose".[26] Henry David Thoreau expressed appreciation in "Thomas Carlyle and His Works":

Indeed, for fluency and skill in the use of the English tongue, he is a master unrivalled. His felicity and power of expression surpass even his special merits as historian and critic. . . . we had not understood the wealth of the language before. . . . He does not go to the dictionary, the wordbook, but to the word-manufactory itself, and has made endless work for the lexicographers . . . it would be well for any who have a lost horse to advertise, or a town-meeting warrant, or a sermon, or a letter to write, to study this universal letter-writer, for he knows more than the grammar or the dictionary.[27]

Oscar Wilde wrote that among the very few masters of English prose, "We have Carlyle, who should not be imitated."[28] Matthew Arnold advised: "Flee Carlylese as you would the devil."[29]

Frederic Harrison deemed Carlyle the "literary dictator of Victorian prose."[30] T. S. Eliot complained that "Carlyle partly originates and partly marks the disturbances in the equilibrium of English prose style", a problem that only disappeared with Ulysses.[31] Indeed, Georg B. Tennyson remarked that "not until Joyce is there a comparable inventiveness in English prose."[32]

Notes

- The "total number of quotations from that author used in the dictionary as examples."

- The "number of quotations that are considered first uses of a word that is a main entry—in other words the author can claim to have used the word first, or to have coined it."

- The "number of words or phrases that are used by the author for the first time in a particular sense, such as figuratively instead of concretely, or for using a particular noun as a verb for the first time, or coining a phrase made from existing known words."

References

- Letters, 8:135.

- Ingram, Malcolm (2013). "Carlylese" (PDF). Carlyle Society Occasional Papers. Edinburgh University Press (26): 5.

- Ingram, Malcolm (2013). "Carlylese" (PDF). Carlyle Society Occasional Papers (26): 8–9.

- Tennyson 1965, p. 251.

- Tennyson 1965, p. 241.

- Cumming 2004, p. 454.

- Works, 26:244.

- Works, 6:2.

- I. Ousby (ed.), The Cambridge Guide to Literature in English (Cambridge, 1995), p. 350.

- Cumming 2004, p. 455.

- Sanders 1977, "The Victorian Rembrandt: Carlyle's Portraits of His Contemporaries".

- Smith, Logan Pearsall. "The Rembrandt of English Prose". Times Literary Supplement, 1934.

- Garnett, Richard. Life of Carlyle. pp. 155–156.

- Ingram, Malcolm (2013). "Carlylese" (PDF). Carlyle Society Occasional Papers. Edinburgh University Press (26): 9–10, 19.

- Cumming 2004, pp. 228–229.

- Cumming 2004, p. 28.

- Cumming 2004, p. 29.

- Sigman, Joseph. "Adam-Kadmonm Nifl, Muspel, and the Biblical Symbolism of Sartor Resartus." ELH 41 (1974): 253–56.

- Cumming 2004, p. 225.

- Clubbe, John. "Carlyle as Epic Historian." In Victorian Literature and Society: Essays Presented to Richard D. Altick, ed. James R. Kincaid and Albert J. Kuhn, 119–45. Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 1984.

- Cumming 2004, pp. 329–330.

- Cumming 2004, p. 425.

- Works, 11:110.

- Seigel, J.P. Thomas Carlyle: The Critical Heritage. 1971. Taylor and Francis eLibrary, 2002.

- Carlyle, Thomas (1915). Carlyle's Scottish & Other Miscellanies with an Introduction by James Russell Lowell. Everyman's Library. p. xi. ISBN 9780665880483.

- Tillotson, Kathleen (1956). Novels of the Eighteen-Forties. London: Oxford University Press. p. 152.

- Thoreau, Henry David. "Thomas Carlyle and His Works". Graham's Magazine, Vol. 30, No. 3–4, March–April, 1847.

- Wilde, Oscar (8 December 1888). "English Poetesses". In Lucas, E. V. (ed.). A Critic in Pall Mall. London: Methuen & Co. Ltd. (published 1919). p. 97.

- Hartman, Geoffrey H. (1980). Criticism in the Wilderness: The Study of Literature Today. New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press. p. 47. ISBN 0300020856.

- Harrison, Frederic (1895). "Characteristics of Victorian Literature". Studies in Early Victorian Literature. London and New York: Edward Arnold.

- Kerry, Pionke & Dent 2018, pp. 4.

- Tennyson, G. B. (1965). Sartor Called Resartus: The Genesis, Structure, and Style of Thomas Carlyle's First Major Work. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. LCCN 65017162. p. 241.

Sources

- Cumming, Mark, ed. (2004). The Carlyle Encyclopedia. Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0838637920.

- Kerry, Paul E.; Pionke, Albert D.; Dent, Megan, eds. (2018). Thomas Carlyle and the Idea of Influence. Madison and Teaneck, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-1683930662.

- Sanders, Charles Richard (1977). Carlyle's Friendships and Other Studies. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0822303893.

- Sanders, Charles Richard; Fielding, Kenneth J.; Ryals, Clyde de L.; Campbell, Ian; Christianson, Aileen; Clubbe, John; McIntosh, Sheila; Smith, Hilary; Sorensen, David, eds. (1970–2022). The Collected Letters of Thomas and Jane Welsh Carlyle. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- Tennyson, G. B. (1965). Sartor Called Resartus: The Genesis, Structure, and Style of Thomas Carlyle's First Major Work. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. LCCN 65017162.

- Traill, Henry Duff, ed. (1896–1899). The Works of Thomas Carlyle in Thirty Volumes. London: Chapman and Hall.

- Vol. I. Sartor Resartus: The Life and Opinions of Herr Teufelsdröckh in Three Books (1831)

- Vols. II–IV. The French Revolution: A History (1837)

- Vol. V. On Heroes, Hero-Worship, and the Heroic in History (1841)

- Vols. VI–IX. Oliver Cromwell's Letters and Speeches: with Elucidations (1845)

- Vol. X. Past and Present (1843)

- Vol. XI. The Life of John Sterling (1851)

- Vols. XII–XIX. History of Friedrich II. of Prussia, Called Frederick the Great (1858–1865)

- Vol. XX. Latter-Day Pamphlets (1850)

- Vols. XXI–XXII. German Romance: Translations from the German, with Biographical and Critical Notices (1827)

- Vols. XXIII–XXIV. Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship and Travels, Translated from the German of Goethe (1824)

- Vol. XXV. The Life of Friedrich Schiller, Comprehending an Examination of His Works (1825)

- Vols. XXVI–XXX. Critical and Miscellaneous Essays