Caroline era

The Caroline era is the period in English and Scottish history named for the 24-year reign of Charles I (1625–1649). The term is derived from Carolus, the Latin for Charles.[1] The Caroline era followed the Jacobean era, the reign of Charles's father James I & VI (1603–1625), overlapped with the English Civil War (1642–1651), and was followed by the English Interregnum until The Restoration in 1660. It should not be confused with the Carolean era which refers to the reign of Charles I's son King Charles II.[2]

| Caroline era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1625 – 1642 (1649) | |||

| |||

| Monarch(s) | Charles I | ||

Chronology

| |||

| Periods in English history |

|---|

| Timeline |

The Caroline era was dominated by growing religious, political, and social discord between the King and his supporters, termed the Royalist party, and the Parliamentarian opposition that evolved in response to particular aspects of Charles's rule. While the Thirty Years' War was raging in continental Europe, Britain had an uneasy peace, growing more restless as the civil conflict between the King and the supporters of Parliament worsened.

Despite the friction between King and Parliament dominating society, there were developments in the arts and sciences. The period also saw the colonisation of North America with the foundation of new colonies between 1629 and 1636 in Carolina, Maryland, Connecticut and Rhode Island. Development of colonies in Virginia, Massachusetts, and Newfoundland also continued. In Massachusetts, the Pequot War of 1637 was the first major armed conflict between the people of New England and the Pequot Tribe.

Arts

The highest standards of the arts and architecture all flourished under the patronage of the King, although drama slipped from the previous Shakespearean age. All the arts were greatly impacted by the enormous political and religious controversies, and the degree to which they were themselves influential is a matter of ongoing debate among scholars. Patrick Collinson argues that an emerging Puritan community was highly suspicious of the fine arts. Edward Chaney argues that Catholic patrons and professionals were quite numerous and greatly influenced the direction of the arts.[3][4][5]

Poetry

The Caroline period saw the flourishing of the cavalier poets (including Thomas Carew, Richard Lovelace, and John Suckling) and the metaphysical poets (including George Herbert, Henry Vaughan, Katherine Philips), movements that produced figures like John Donne, Robert Herrick and John Milton.[6]

Cavalier poetry differs from traditional poetry in subject matter. Instead of tackling issues such as religion, philosophy and the arts, cavalier poetry aims to express the joys and celebrations in a much livelier way than did its predecessors. The intent was often to promote the crown, and they often spoke outwardly against the Roundheads. Most cavalier works had allegorical or classical references, drawing on knowledge of Horace, Cicero, and Ovid.[7] By using these resources they were able to produce poetry that impressed King Charles I. The cavalier poets strove to create poetry where both pleasure and virtue thrived. They were rich in reference to the ancients, and most poems "celebrate beauty, love, nature, sensuality, drinking, good fellowship, honor, and social life".[8]

Cavalier poets wrote in a way that promoted seizing the day and the opportunities presented to them and their kinsmen. They wanted to revel in society and come to be the best that they possibly could within the bounds of that society. Living life to the fullest, for cavalier writers, often included gaining material wealth and having sex with women. These themes contributed to the triumphant and boisterous tone and attitude of the poetry. Platonic love was also another characteristic of cavalier poetry, where the man would show his divine love for a woman, and where she would be worshipped as a creature of perfection.[9]

George Wither (1588–1667) was a prolific poet, pamphleteer, satirist and writer of hymns. He is best known for "Britain's Remembrancer" of 1625, with its wide range of contemporary topics including the plague and politics. It reflects on nature of poetry and prophecy, explores the fault lines in politics, and rejects tyranny of the sort the king was denounced for fostering. It warns about the wickedness of the times and prophesizes that disasters are about to befall the kingdom.[10]

Theatre

Caroline theatre unquestionably saw a falling-off after the peak achievements of William Shakespeare and Ben Jonson, though some of their successors, especially Philip Massinger, James Shirley, and John Ford, carried on to create interesting, even compelling theatre. In recent years the comedies of Richard Brome have gained in critical recognition.

The peculiar artistic form of the court masque was still being written and performed. A masque involved music and dancing, singing and acting, within an elaborate stage design, in which the architectural framing and costumes might be designed by a renowned architect, often Inigo Jones,[11] to present a deferential allegory flattering to the patron.[12] Professional actors and musicians were hired for the speaking and singing parts. Often those acting, who did not speak or sing, were courtiers. In a strong contrast to Jacobean and Elizabethan theatre, seen by a very wide public, these were private performances in houses or palaces for a small court audience.

The lavish expenditures on these showpiece masques – the production of a single masque could approach £15,000[13] – was one of a growing number of grievances that critics in general, and the Parliamentarians in particular, held against the King and his court.

The conventional theatre in London also continued the Jacobean trend of moving to smaller, more intimate, but also more expensive venues, performing in front of a much narrower social range. The only new London theatre in the reign seems to have been the Salisbury Court Theatre, open from 1629 until the closing of the theatres in 1642. Sir Henry Herbert as (in theory) deputy Master of the Revels, was a dominant figure, in the 1630s often causing trouble for the two leading companies, the King's Men, whose patronage Charles had inherited from his father, and Queen Henrietta's Men, formed in 1625, partly from earlier companies under the patronage of Charles' mother and sister. The theatres were closed for a long time because of plague in 1638–39, although after the Long Parliament officially closed them for good in 1642, private performances continued, and at some periods public ones.

In other forms of literature, and especially in drama, the Caroline period was a diminished continuation of the trends of the previous two reigns. In the specialized domain of literary criticism and theory, Henry Reynolds' Mythomystes was published in 1632, in which the author attempts a systematic application of Neoplatonism to poetry. The result has been characterized as "a tropical forest of strange fancies" and "perversities of taste."[14]

Painting

Charles I can be compared to King Henry VIII and King George III as a highly influential royal collector; he was by far the keenest collector of art of all the Stuart kings.[15] He saw painting as a way of promoting his elevated view of the monarchy. His collection reflected his aesthetic tastes, which contrasted with the systematic acquisition of a wide range of objects that was typical of contemporary German and Habsburg princes.[16] By his death, he had amassed about 1,760 paintings, including works by Titian, Raphael and Correggio among others.[17][18] Charles commissioned the ceiling of the Banqueting House, Whitehall from Rubens and paintings by artists from the Low Countries such as Gerard van Honthorst and Daniel Mytens.[19] In 1628, he bought the collection that the Duke of Mantua was forced to sell. In 1632, the peripatetic king visited Spain, where he sat for a portrait by Diego Velázquez, although the picture is now lost.[20]

As king he worked to entice leading foreign painters to London for longer or shorter spells. In 1626, he was able to persuade Orazio Gentileschi to settle in England, later to be joined by his daughter Artemisia and some of his sons. Rubens was a particular target: eventually in 1630 he came on a diplomatic mission that included painting, and he later sent Charles more paintings from Antwerp. Rubens was very well treated during his nine-month visit, during which he was knighted.[21] Charles's court portraitist was Daniël Mijtens.[22]

Van Dyck

Anthony van Dyck (appointed "painter to the king," 1633–1641)[23] was a dominant influence. Often in Antwerp, but closely in touch with the English court, he assisted King Charles's agents in their search for pictures. Van Dyck also sent back some of his own works and had painted Charles's sister, Queen Elizabeth of Bohemia, at The Hague in 1632. Van Dyck was knighted and given a pension of £200 a year, in a grant in which he was described as principalle Paynter in ordinary to their majesties.[23] He was provided with a house on the River Thames at Blackfriars, and a suite of rooms in Eltham Palace. His Blackfriars studio was frequently visited by the King and Queen, who hardly sat for another painter while van Dyck lived.[24]

Van Dyck undertook a large series of portraits of the King and Queen Henrietta Maria, as well as their children and some courtiers. Many were completed in several versions and used as diplomatic gifts or given to supporters of the increasingly embattled king.[25] Van Dyck's subjects appear relaxed and elegant but with an overarching air of authority, a tone that dominated English portrait painting until the end of the 18th century. Many of the portraits have lush landscape backgrounds. His portraits of Charles on horseback updated the grandeur of Titian's Emperor Charles V, but even more effective and original is his portrait in the Louvre of Charles dismounted: "Charles is given a totally natural look of instinctive sovereignty, in a deliberately informal setting where he strolls so negligently that he seems at first glance nature's gentleman rather than England's King".[26] Although he established the classic "Cavalier" style and dress, a majority of his most important patrons took the Parliamentarian side in the English Civil War that broke out soon after his death.[24]

Upon his death in 1641, van Dyke's position as portraitist to the royal family was filled, practically if not formally, by William Dobson (c. 1610–1646), who is known to have had access to the Royal Collection and copied works by Titian and van Dyck. Dobson was thus the most prominent native-born English artist of the era.[27]

Architecture

The Classical architecture popular in Italy and France was introduced to Britain during the Caroline era; until then Renaissance architecture had largely passed Britain by. The style arrived in the form of Palladianism, the most influential pioneer of the style was the Englishman Inigo Jones.[28] Jones travelled throughout Italy with the 'Collector' Earl of Arundel, annotating his copy of Palladio's treatise, in 1613–1614.[29] The "Palladianism" of Jones and his contemporaries and later followers was a style largely of facades, and the mathematical formulae dictating layout were not strictly applied. A handful of great country houses in England built between 1640 and 1680, such as Wilton House, are in this Palladian style. These follow the success of Jones' Palladian designs for the Queen's House at Greenwich and the Banqueting House at Whitehall (the residence of English monarchy from 1530 to 1698), and the uncompleted royal palace in London of Charles I.[30]

.JPG.webp)

Jones's St Paul's, Covent Garden (1631) was the first completely new English church since the Reformation, and an imposing transcription of the Tuscan order as described by Vitruvius – in effect Early Roman or Etruscan architecture. Possibly "nowhere in Europe had this literal primitivism been attempted", according to Sir John Summerson.[31]

Jones was a figure of the court, and most commissions for large houses during the reign were built in a style for which Summerson's name "Artisan Mannerism" has been widely accepted. This was a development of Jacobean architecture led by a group of mostly London-based craftsmen still active in their guilds (called livery companies in London). Often the names of the architects or designers are uncertain, and often the main building contractor played a large part in the design. The most prominent of these, and also the leading native sculptor of the period, was the stonemason Nicholas Stone, who also worked with Inigo Jones. John Jackson (d. 1663) was based in Oxford, and made additions to various colleges there.[32]

The owner of Swakeleys House (1638), now on the edge of London, was a merchant who became Lord Mayor of London in 1640, and the house shows "what a gulf there was between the taste of the Court and that of the City." It features prominently the fancy quasi-classical gable ends that were a mark of the style. Other houses from the 1630s in the style are the "Dutch House", as it was known, now Kew Palace, Broome Park in Kent, Barnham Court in West Sussex, West Horsley Place and Slyfield Manor, the last two near Guildford. These are mainly in brick, apart from stone or wood mullions. The interiors often show a riot of decoration, as carpenters and stuccoists were given their head.[33]

Raynham Hall in Norfolk (1630s), where the origins of the design have been much discussed, also features large and proud gable ends, but in a far more restrained fashion, that reflects Italian influence, by whatever route it came.[34]

Following the execution of Charles I, the Palladian designs advocated by Inigo Jones were too closely associated with the court of the late king to survive the turmoil of the Civil War. Following the Stuart restoration, Jones's Palladianism was eclipsed by the Baroque designs of such architects as William Talman and Sir John Vanbrugh, Nicholas Hawksmoor, and even Jones' pupil John Webb.[35]

Science

Medicine

Medicine saw a major step forward with the 1628 publication by William Harvey of his study of the circulatory system, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus ("An Anatomical Exercise on the Motion of the Heart and Blood in Living Beings"). Its reception was highly critical and hostile; but within a generation his work began to receive the valuation it deserved.

Countering medical progress, the occultist Robert Fludd continued his series of enormous and convoluted volumes of esoteric lore, begun during the previous reign. In 1626 appeared his Philosophia Sacra (which constituted Portion IV of Section I of Tractate II of Volume II of Fludd's History of the Macrocosm and Microcosm), which was followed in 1629 and 1631 by the two-part medical text Medicina Catholica.[36] Fludd's last major work would be the posthumously published Philosophia Moysaica.[37]

Philosophy

The revolution in thinking that connects Sir Francis Bacon (1561–1626) with the foundation of the Royal Society (1660) was ongoing throughout the Caroline period; Bacon's New Atlantis was first printed in 1627, and contributed to the evolving new paradigm among receptive individuals. The men who would begin the Royal Society were for the most part still schoolboys and students in this period—though John Wilkins was already publishing early works of Copernican astronomy and science advocacy, The Discovery of a World in the Moon (1638) and A Discourse Concerning a New Planet (1640).

Lacking formal scientific institutions and organisations, Caroline scientists, proto-scientists, and "natural philosophers" had to cluster in informal groups, often under the social and financial patronage of a sympathetic aristocrat. This again was an old phenomenon: a precedent in the prior reigns of Elizabeth and James can be identified in the circle that revolved around the "Wizard Earl" of Northumberland. Caroline scientists often clustered similarly. These ad hoc associations led to a decline in mystical philosophies popular at the time, such as alchemy and astrology, Neoplatonism and Kabbalah and sympathetic magic.

Mathematics

In mathematics, two major works were published in a single year, 1631. Thomas Harriot's Artis analyticae praxis, published ten years posthumously, and William Oughtred's Clavis mathematicae. Both contributed to the evolution of modern mathematical language; the former introduced the sign for multiplication and (::) sign for proportion.[38][39] In philosophy, Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) was already writing some of his works and evolving his key concepts, though they were not in print until after the end of the Caroline era.

Religion

Regardless of religious doctrine or political belief, the vast majority in all three kingdoms believed a 'well-ordered' monarchy was divinely mandated. They disagreed on what 'well-ordered' meant, and who held ultimate authority in clerical affairs. Episcopalians generally supported a church governed by bishops, appointed by, and answerable to, the king; Puritans believed he was answerable to the leaders of the church, appointed by their congregations.[40]

The Caroline period was one of intense debate over religious practice and liturgy. While the Church of Scotland, or kirk, was overwhelmingly Presbyterian, the position in England was more complex. 'Puritan' was a general term for anyone who wanted to reform, or 'purify', the Church of England, and contained many different sects. Presbyterians were the most prominent, particularly in Parliament, but there were many others, such as Congregationalists, often grouped together as Independents. Close links between religion and politics added further complexity; bishops sat in the House of Lords, where they often blocked Parliamentary legislation.[41]

Although Charles was firmly Protestant, even among those who supported Episcopalianism, many opposed the High church rituals he sought to impose in England and Scotland. Often seen as essentially Catholic, these caused widespread suspicion and mistrust.[42] Genuinely felt, there were a number of reasons for this; first, close links between 17th century religion and politics meant alterations in one were often viewed as implying alterations in the other. Second, in a period dominated by the Thirty Years' War, it reflected concerns Charles was failing to support Protestant Europe, when it was under threat from Catholic powers.[43]

Charles worked closely with Archbishop William Laud (1573–1645) on remodelling the church, including preparation of a new Book of Common Prayer. Historians Kevin Sharpe and Julian Davies suggest Charles was the prime instigator of religious change, with Laud ensuring the appointment of key supporters, such as Roger Maynwaring and Robert Sibthorpe.[44][45]

Scottish resistance to Caroline reforms ended with the 1639 and 1640 Bishops Wars, which expelled bishops from the kirk, and established a Covenanter government. Following the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant, the English and Scots set up the Westminster Assembly, intending to create a unified, Presbyterian church of England and Scotland. However, it soon became clear such a proposal would not be approved, even by the Puritan dominated Long Parliament, and it was abandoned in 1647.[46]

Foreign policy

King James I (reigned 1603–1625) was sincerely devoted to peace, not just for his three kingdoms, but for Europe as a whole.[47] Europe was deeply polarised, and on the verge of the massive Thirty Years' War (1618–1648), with the smaller established Protestant states facing the aggression of the larger Catholic empires. The Catholics in Spain, as well as the Emperor Ferdinand II, the Vienna-based leader of the Habsburgs and head of the Holy Roman Empire, were both heavily influenced by the Catholic Counter-Reformation. They had the goal of expelling Protestantism from their domains.[48]

Charles inherited a weak navy and the early years of the era saw numerous ships lost to Barbary pirates, in the pay of the Ottoman empire, whose prisoners became slaves. This extended to coastal raids, such as the taking of 60 people in August 1625 from Mount's Bay, Cornwall, and it is estimated that by 1626, 4,500 Britons were held in captivity in North Africa. Ships continued to be seized even in British waters, and by the 1640s, Parliament was passing measures to raise money to ransom hostages from the Turks.[49]

The Duke of Buckingham (1592–1628), who increasingly was the actual ruler of Britain, wanted an alliance with Spain. Buckingham took Charles with him to Spain to woo the Infanta in 1623. However, Spain's terms were that James must drop Britain's anti-Catholic intolerance or no marriage. Buckingham and Charles were humiliated and Buckingham became the leader of the widespread British demand for a war against Spain. Meanwhile, the Protestant princes looked to Britain, since it was the strongest of all the Protestant countries, to give military support for their cause. His son-in-law and daughter became king and queen of Bohemia, which outraged Vienna. The Thirty Years' War began in 1618, as the Habsburg Emperor ousted the new king and queen of Bohemia, and massacred their followers. Catholic Bavaria then invaded the Palatine, and James's son-in-law begged for James's military intervention. James finally realised his policies had backfired and refused these pleas. He successfully kept Britain out of the European-wide war that proved so heavily devastating for three decades. James's backup plan was to marry his son Charles to a French Catholic princess, who would bring a handsome dowry. Parliament and the British people were strongly opposed to any Catholic marriage, were demanding immediate war with Spain, and strongly favored with the Protestant cause in Europe. James had alienated both elite and popular opinion in Britain, and Parliament was cutting back its financing. Historians credit James for pulling back from a major war at the last minute, and keeping Britain in peace.[50][51]

Charles trusted Buckingham, who made himself rich in the process but proved a failure at foreign and military policy. Charles I gave him command of the military expedition against Spain in 1625. It was a total fiasco with many dying from disease and starvation. He led another disastrous military campaign in 1627. Buckingham was hated and the damage to the king's reputation was irreparable. England rejoiced when he was assassinated in 1628 by John Felton.[52]

The eleven years 1629–1640, during which Charles ruled England without a Parliament, are referred to as the Personal Rule. There was no money for war so peace was essential. Without the means in the foreseeable future to raise funds from Parliament for a European war, or the help of Buckingham, Charles made peace with France and Spain.[53] Lack of funds for war, and internal conflict between the king and Parliament led to a redirection of English involvement in European affairs – much to the dismay of Protestant forces on the continent. This involved a continued reliance on the Anglo-Dutch brigade as the main agency of English military participation against the Habsburgs, although regiments also fought for Sweden thereafter. The determination of James I and Charles I to avoid involvement in the continental conflict appears in retrospect as one of the most significant, and most positive, aspects of their reigns. There was a small naval Anglo-French War (1627–1629), in which the England supported the French Huguenots against King Louis XIII of France.[54]

During 1600–1650 England made repeated efforts to colonise Guiana in South America. They all failed and the lands (Surinam) were ceded to the Dutch in 1667.[55][56]

Colonial developments

Between 1620 and 1643, religious dissatisfaction, mostly from Puritans and those opposed to the King's purported Catholic leanings, led to large scale voluntary emigration, which later came to be known as The Great Migration. Of the estimated 80,000 emigrants from England, approximately 20,000 settled in North America, Where New England was most often the destination.[57] The colonists to New England were mostly families with some education who were leading relatively prosperous lives in England.

Carolina

In 1629, King Charles granted his attorney-general, Sir Robert Heath, the Cape Fear region of what is now the United States. It was incorporated as the Province of Carolana, named in honour of the King. Heath attempted and failed to populate the province, but lost interest and eventually sold it to Lord Maltravers.[58] The first permanent settlers to Carolina arrived during the reign of Charles II, who issued a new charter.

Maryland

In 1632, King Charles I granted a charter for Maryland, a proprietary colony of about twelve million acres (49,000 km2), to the Roman Catholic 2nd Baron Baltimore who wanted to realise his father's ambition of founding a colony where Catholic's could live in harmony alongside Protestants. Unlike the royal charter granted for Carolina to Robert Heath, the Maryland charter decreed no stipulations regarding future settlers' religious beliefs. Therefore, it was assumed that Catholics would be able live unmolested in the new colony.[61] The new colony was named after the devoutly Catholic Henrietta Maria of France, Charles I's wife and Queen Consort.[62][63]

Whatever the King's reason for granting the colony to Baltimore, it suited his strategic policies to have a colony north of the Potomac in 1632. The colony of New Netherland begun by England's great imperial rival, the Dutch United Provinces, which claimed the Delaware River valley and was deliberately vague about its border with Virginia. Charles rejected all the Dutch claims on the Atlantic seaboard and wanted to maintain English claims by formally occupying the territory.

Lord Baltimore sought both Catholic and Protestant settlers for Maryland, often enticing them with large grants of land and a promise of religious toleration. The new colony also used the headright system, which originated in Jamestown, whereby settlers were given 50 acres (20 ha) of land for each person they brought into the colony. However, Of the approximately 200 initial settlers who travelled to Maryland on the ships Ark and Dove, the majority were Protestant.[64] The Roman Catholics, already a minority, led by a Jesuit Father Andrew White worked together with Protestants, under the patronage of Leonard Calvert, the 2nd Lord Baltimore's brother to create a new settlement, St. Mary's City. This became the first capital of Maryland.[65] Today, the city is considered the birthplace of religious freedom in the United States,[66][67] with the earliest North American colonial settlement ever established with the specific mandate of being a haven for both Catholic and Protestant Christian faiths.[66][68][69] Roman Catholics were, though, encouraged to be reticent regarding their faith in order not to cause discord with their Protestant neighbours.[69]

Religious tolerance continued to be an aspiration and in the province's first legislative assembly the Maryland Toleration Act of 1649 was passed, enshrining religious freedom in law. Later in the century, the Protestant Revolution put an end to Maryland's religious toleration, as Catholicism was outlawed. Religious toleration would not be restored in Maryland until after the American Revolution.[70]

Connecticut

The Connecticut Colony was originally a number of small settlements at Windsor, Wethersfield, Saybrook, Hartford, and New Haven. The first English settlers arrived in 1633 and settled at Windsor.[71] John Winthrop the Younger of Massachusetts received a commission to create Saybrook Colony at the mouth of the Connecticut River in 1635.[72]

The main body of settlers – Puritans from Massachusetts Bay Colony, led by Thomas Hooker – arrived in 1636 and established the Connecticut Colony at Hartford.[73] The Quinnipiac Colony ... [74] The New Haven Colony was established by John Davenport, Theophilus Eaton, and others in March 1638. This colony had its own constitution called "The Fundamental Agreement of the New Haven Colony" ratified in 1639.[75]

The Caroline era settlers held Calvinist religious beliefs and maintained a separation from the Church of England. Mostly they had immigrated to New England during the Great Migration.[76] These individually independent settlements were unsanctioned by the Crown.[77] Official recognition did not come until the Carolean era.[78]

Rhode Island (1636)

What would become the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations (commonly shortened to merely Rhode Island) was founded during the Caroline era. Dissenters from the Puritan-dominated Massachusetts Bay Colony moved into the area in two separate waves during the 1630s. The first, led by Roger Williams in 1636, settled the Providence Plantations, today the modern city of Providence, Rhode Island as well as including neighbouring communities such as Cranston (then Patuxent). A year later, a different group led by Anne Hutchinson, settled on the northern part of Aquidneck Island (then known as Rhode Island). This was following her trial and banishment during the Antinomian Controversy, a key politico-religious movement in New England at the time. Another dissenter that was originally part of Williams's party, Samuel Gorton, later split from that group and founded his own settlement of Shawomet Purchase in 1642, today this is the community of Warwick. After some conflicts between Gorton's settlement and the already established and chartered Massachusetts Bay Colony, Gorton travelled back to England and received orders from Robert Rich, 2nd Earl of Warwick for Massachusetts Bay to allow the settlements to manage their own affairs. While this fell short of a full charter, it did grant the Providence and Rhode Island settlements some degree of autonomy, until the Rhode Island Royal Charter of 1663 officially recognised the colony as fully independent of Massachusetts Bay.

Barbados

After visits by Portuguese and Spanish explorers, Barbados was claimed on 14 May 1625 for James I (who had died six weeks earlier) by Captain John Powell.[79] Two years later, a party of 80 settlers and 10 slaves, led by his brother, Captain Henry Powell, occupied the island.[80] In 1639 the colonists established a local democratic assembly. Agriculture, reliant on indenture, was developed by the introduction of sugar cane, tobacco and cotton, beginning in the 1630s.[79]

End of the era

After Charles' abortive attempt to arrest five members of Parliament on 4 January 1642, the over-confident King declared war on Parliament and the Civil War began with the King fighting the armies of both the English and Scottish parliaments.

A key supporter of Charles was his nephew Prince Rupert (1619–82), third son of Elector Palatine Frederick V and Elizabeth, sister of Charles. He was the most brilliant and dashing of Charles I's generals and the dominant royalist during the Civil War. He was also active in the British navy, a founder-director of the Royal African Company and the Hudson's Bay Company, a scientist, and an artist.[81]

Following Charles' defeat at the Battle of Naseby in June 1645, he surrendered to the Scottish parliamentary army which eventually handed him over to the English Parliament. Held under house arrest at Hampton Court Palace, Charles steadfastly refused demands for a constitutional monarchy. In November 1647 he fled from Hampton Court but, but was quickly recaptured and imprisoned by Parliament in the more secure Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight.[82][83]

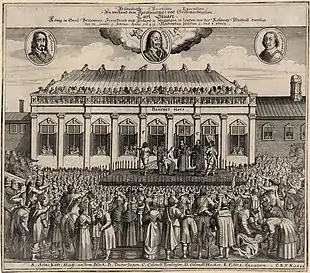

At Carisbrooke, Charles still intriguing and plotting futile escapes managed to forge an alliance with Scotland, by promising to establish Presbyterianism, and a Scottish invasion of England was planned.[84] However, by the end of 1648 Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army had consolidated its control over England and the invading Scots were defeated at the Battle of Preston where 2,000 of Charles' troops were killed and a further 9,000 captured.[85] The King, now truly defeated, was charged with the crimes of tyranny and treason.[86] The King was tried, convicted, and executed in January 1649.[86]

His execution took place outside a window of Inigo Jones' Banqueting House, with its ceiling Charles's had commissioned from Rubens as the first phase of his new royal palace.[87][88] The palace was never completed and the King's art collection dispersed.[88] In his lifetime Charles accumulated enemies who mocked his artistic interests as an extravagant expenditures of state funds, and whispered that he fell under the influence of Cardinal Francesco Barberini, the pope's nephew who was also a distinguished collector.[89] The high points of English culture became a major casualty of the Puritan victory in the Civil War.[90] They closed theaters and impeded poetic drama, but most significantly they ended royal and court patronage of artists and musicians.[88] Following the King's execution, under The Protectorate, with the exception of sacred music and, in its latter years, opera, the arts did not flourish again until The Restoration and beginning of the Carolean era in 1660 under Charles II.[91]

See also

References

- Hirsch, Edward (2014). A Poet's Glossary. p. 93. ISBN 9780547737461.

- Oxford Reference retrieved 20 February 2020.

- Tim Wilks, "Art, Architecture and Politics" in Barry Coward, ed. A Companion to Stuart Britain (2008) pp. 187–213.

- Patrick Collinson, The Birthpangs of Protestant England: Religious and Cultural Change in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (1988).

- Edward Chaney, ed. The evolution of English collecting: receptions of Italian art in the Tudor and Stuart periods (2004).

- Thomas N. Corns, "The Poetry of the Caroline Court." Proceedings-British Academy Vol. 97. (1998) pp. 51–73. online Archived 3 March 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- Clayton, Thomas (Spring 1974). "The Cavalier Mode from Jonson to Cotton by Earl Miner". Renaissance Quarterly. 27 (1): 111. doi:10.2307/2859327. JSTOR 2859327. S2CID 199289537.

- The Broadview Anthology of Literature: The Renaissance and The Early Seventeenth Century. Canada: Broadview Press. 2006. p. 790. ISBN 1-55111-610-3.

- Larsen, Eric (Spring 1972). "Van Dyck's English Period and Cavalier Poetry". Art Journal. 31 (3): 257. doi:10.2307/775510. JSTOR 775510.; Adamson, John (20 February 2011). "Reprobates: The Cavaliers of the English Civil War, John Stubbs: review". The Telegraph. UK. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Andrew McRae, "Remembering 1625: George Wither's Britain's Remembrancer and the Condition of Early Caroline England" English Literary Renaissance 46.3 (2016): 433–455.

- Summerson, 104-106

- Chambers, p75.

- William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle, spent between £14,000 and £15,000 on staging Jonson's last masque, Love's Welcome at Bolsover, for the King and Queen on 30 July 1634. Henry Ten Eyck Perry, The First Duchess of Newcastle and Her Husband as Figures in Literary History, Boston, Ginn and Co., 1918; p. 18.

- Cambridge History of English and American Literature, Vol. VII.

- Doreen Agnew, "Royal Collectors in England," History Today (May 1953) 3#5 pp. 339–351.

- Arthur MacGregor, "King Charles I: A Renaissance Collector?." The Seventeenth Century 11.2 (1996) pp: 141-160.

- Carlton, p. 143

- Gregg, p. 83

- Carlton (1995), p. 145; Hibbert (1968), p.134

- Harris, p. 12

- Michael Jeffé, "Charles the First and Rubens," History Today (Jan 1951) 1#1 pp. 61–73.

- The Met Museum: Charles I (1600–1649), King of England, 1629, Daniël Mijtens, Dutch. retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Grosvenor Gallery; Stephens, F.G. (1887). Exhibition of the Works of Sir Anthony Van Dyck. H. Good and Son, Printers. p. 14.

About the end of March or the beginning of April, 1632, Van Dyck arrived in England; he was almost immediately appointed Principal Painter in Ordinary to the King, knighted, presented with a gold chain....

- Cust, 1899

- Gaunt, William (1980). Court Painting in England : From Tudor to Victorian Times. Little, Brown Book Group Limited. ISBN 9780094618701.

- Levey p. 128

- Ellis Waterhouse, Painting in Britain 1530 to 1790, fourth edition, New York, Viking Penguin, 1978; pp. 80–5.

- Summerson, 104-133 covers Jone's whole career

- Hanno-Walter Kruft. A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present. Princeton Architectural Press, 1994 and Edward Chaney, Inigo Jones's 'Roman Sketchbook, 2006).

- Copplestone, p. 280

- Summerson, 125-126, 126 quoted

- Summerson, 142-144

- Summerson, 142-147, 145 quoted

- Summerson, 145-147

- Copplestone, p. 281

- Medicina Catholica, &c., Frankfort, 1629–31, in five parts; the plan included a second volume, not published.

- Philosophia Moysaica, &c., Gouda, 1638; an edition in English, Mosaicall Philosophy, &c., London, 1659

- Carl B. Boyer, A History of Mathematics, second edition, revised by Uta C. Merzbach; New York, John Wiley, 1991; pp. 306–7.

- Pycior, Helena Mary. Symbols, Impossible Numbers, and Geometric Entanglements: British Algebra through the Commentaries on Newton's Universal Arithmetick. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. p. 48. ISBN 0-521-48124-4

- Macleod 2009, pp. 5–19 passim.

- Wedgwood 1958, p. 31.

- Charles I. royal.uk. Retrieved 1 March 2020

- MacDonald 1969, pp. 45–50.

- Kenneth Fincham, "William Laud and the exercise of Caroline ecclesiastical patronage." Journal of Ecclesiastical History 51.1 (2000): 69–93.

- Julian Davies, The Caroline captivity of the church: Charles I and the remoulding of Anglicanism, 1625–1641 (Oxford UP, 1992).

- Wedgwood 1958, pp. 603–605.

- Lockyer, Roger (1998). James VI and I. Longman. pp. 138–58. ISBN 9780582279629.

- W. B. Patterson, "King James I and the Protestant cause in the crisis of 1618–22." Studies in Church History 18 (1982): 319–334.

- Matar, Nabil (1998). Islam in Britain, 1558-1685. Cambridge University Press. pp. 6–9. ISBN 978-0-521-62233-2.

- Jonathan Scott, England's Troubles: 17th-century English Political Instability in European Context (Cambridge UP, 2000), pp. 98–101

- Godfrey Davies, The Early Stuarts: 1603–1660 (1959), pp. 47–67

- Thomas Cogswell, "John Felton, popular political culture, and the assassination of the duke of Buckingham." Historical Journal 49.2 (2006): 357–385.

- Kevin Sharpe, The personal rule of Charles I (1992) xv, 65-104.

- G.M.D. Howat, Stuart and Cromwellian Foreign Policy (1974) pp. 17–42.

- Joyce Lorimer, "The failure of the English Guiana ventures 1595–1667 and James I's foreign policy." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 21#.1 (1993): 1–30.

- Albert J. Loomie, Spain & the Early Stuarts, 1585–1655 (1996).

- Ashley, Roscoe Lewis (1908). American History. New York: The Macmillan Company. p. 52.

- NC Pedia. Herbert R. Paschal, Jr., 1988: Howard, Henry Frederick Retrieved 27 February 2020]

- King, Julia A. (2012). Archaeology, Narrative, and the Politics of the Past: The View from Southern Maryland. Univ. of Tennessee Press. p. 52. ISBN 978-1572338883.

- King, Julia A. (2012). Archaeology, Narrative, and the Politics of the Past: The View from Southern Maryland. Univ. of Tennessee Press. p. 85. ISBN 978-1572338883.

- Sparks, Jared (1846). The Library of American Biography: George Calvert, the first Lord Baltimore. Boston: Charles C. Little and James Brown. pp. 16–.

Leonard Calvert.

- "Maryland's Name & Queen Henrietta Maria". Mdarchives.state.md.us.

- Frances Copeland Stickles, A Crown for Henrietta Maria: Maryland's Namesake Queen (1988), p. 4

- Knott, Aloysius. "Maryland." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910

- Cho, Ah-Hyun (8 November 2005). "Buildings Pay Homage to GU's Most Famous Founders, Donors". The Hoya. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- Greenwell, Megan (21 August 2008). "Religious Freedom Byway Would Recognize Maryland's Historic Role". Washington Post.

- "Reconstructing the Brick Chapel of 1667", page 1, See section entitled "The Birthplace of Religious Freedom" "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2014. Retrieved 3 May 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - "Two Acts of Toleration: 1649 and 1826". Maryland State Archives (online). Retrieved 1 March 2020

- Cecilius Calvert, "Instructions to the Colonists by Lord Baltimore, (1633)" in Clayton Coleman Hall, ed., Narratives of Early Maryland, 1633-1684 (NY: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910), 11-23.

- Roarke, p. 78

- "Early Settlers of Connecticut". Connecticut State Library. Archived from the original on 20 April 2010. Retrieved 25 July 2010.

- "Brief History of Old Saybrook". Old Saybrook Historical Society. Archived from the original on 16 May 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "1636-Hartford". The Society of Colonial Wars in Connecticut. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- Tyler, Edward Royall; Kingsley, William Lathrop; Fisher, George Park; et al., eds. (1887). New Englander and Yale Review. Vol. 47. W.L. Kingsley. pp. 176–177.

- "Fundamental Agreement, or Original Constitution of the Colony of New Haven, June 4, 1639". The Avalon Project: Documents in Law, History and Diplomacy. Yale Law School. 18 December 1998. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- Barck, Oscar T.; Lefler, Hugh T. (1958). Colonial America. New York: Macmillan. pp. 258–259.

- "1638—New Haven—The Independent Colony". The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. Archived from the original on 15 November 2014. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "1662-Charter for Connecticut". The Society of Colonial Wars in the State of Connecticut. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- "The Abbreviated History of Barbados". barbados.org. Retrieved 1 March 2020.

- Beckles, Hilary McD (16 November 2006). A history of Barbados : from Amerindian settlement to Caribbean single market (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0521678490.

- Hugh Trevor-Roper, "Prince Rupert, 1619-82" History Today (March 1982) 32#3:4–11.

- Carlton (1995) p. 331

- Gregg, p. 42

- English Heritage, Charles I: A Royal prisoner at Carisbrooke Castle. english-heritage.org.uk. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- Bull and Seed; p100

- Westminster Hall. The trial of Charles I. UK Parliament. Retrieved 21 February 2020

- Hibbert; p. 267

- Halliday, p. 160

- MacGregor, "King Charles I: A Renaissance Collector?"

- Wilks, "Art, Architecture and Politics" in Barry Coward, ed. A Companion to Stuart Britain (2008) pp. 198–201.

- Halliday, pp. 160–163

Sources

- Brown, Christopher: Van Dyck 1599–1641. Royal Academy Publications, 1999. ISBN 0-900946-66-0

- Bull, Stephen; Seed, Mike (1998). Bloody Preston: The Battle of Preston, 1648. Lancaster: Carnegie Publishing Ltd. ISBN 1-85936-041-6.

- Carlton, Charles (1995). Charles I: The Personal Monarch. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12141-8

- Chambers, James (1985). The English House. London: Guild Publishing.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Copplestone, Trewin (1963). World Architecture. Hamlyn.

- Corns Thomas N. (1999) The Royal Image: Representations of Charles I Cambridge University Press.

- Coward, Barry, and Peter Gaunt, eds (2011). English Historical Documents, 1603–1660

- Cust, Lionel Henry (1899). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 58. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Gregg, Pauline (1981), King Charles I, London: Dent, ISBN 0-460-04437-0

- Halliday, E. E. (1967). Cultural History of England. London: Thames & Hudson.

- Hanno-Walter Kruft. A History of Architectural Theory: From Vitruvius to the Present. Princeton Architectural Press, 1994 and Edward Chaney, Inigo Jones's 'Roman Sketchbook, 2006

- Harris, Enriqueta (1982). Velazquez. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801415268

- Hibbert, Christopher (1968), Charles I, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson

- Kenyon, J.P. ed. The Stuart Constitution, 1603–1688: Documents and Commentary (1986)* Key, Newton, and Robert O. Bucholz, eds. Sources and debates in English history, 1485–1714 (2009)

- MacDonald, William W (1969). "John Pym: Parliamentarian". Historical Magazine of the Protestant Episcopal Church. 38 (1).

- Macleod, Donald (Autumn 2009). "The influence of Calvinism on politics" (PDF). Theology in Scotland. XVI (2).

- Stater, Victor, ed. The Political History of Tudor and Stuart England: A Sourcebook (Routledge, 2002) online

- Summerson, John, Architecture in Britain, 1530–1830, 1991 (8th edn., revised), Penguin, Pelican history of art, ISBN 0140560033

- Wedgwood, CV (1958). The King's War, 1641–1647 (2001 ed.). Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0141390727.

- Williamson, George Charles (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 5. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Wood, Jeremy. Dyck, Sir Anthony Van (1599–1641).

Bibliography

- Atherton, Ian, and Julie Sanders, eds. The 1630s: Interdisciplinary Essays on Culture and Politics in the Caroline Era (Manchester UP, 2006).

- Brice, Katherine. The Early Stuarts, 1603–1640 (1994). pp. 119–143.

- Cogswell, Thomas. "'A Low Road to Extinction? Supply and Redress of Grievances in the Parliaments of the 1620s," Historical Journal, 33#2 (1990), 283–303 DOI: notes online

- Coward, Barry, and Peter Gaunt. The Stuart Age: England, 1603–1714 (5th ed 2017) new introduction; a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

- Coward, Barry, ed. A Companion to Stuart Britain (2009) excerpt and text search; 24 advanced essays by scholars; emphasis on historiography; contents

- Cressy, David. Charles I and the People of England (Oxford UP, 2015).

- Davies, Godfrey. The Early Stuarts, 1603–1660 (Oxford History of England) (2nd ed. 1959), a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

- Dyson, Jessica. Staging Authority in Caroline England: Prerogative, Law and Order in Drama, 1625–1642 (2016).

- Fritze, Ronald H. and William B. Robison, eds. Historical Dictionary of Stuart England, 1603–1689 (1996), 630pp; 300 short essays by experts emphasis on politics, religion, and historiography excerpt

- Gardiner, Samuel Rawson. History of England from the Accession of James I. to the Outbreak of the Civil War 1603-1642 (1884) pp 50–160 online.

- Hirst, Derek. "Of Labels and Situations: Revisionisms and Early Stuart Studies." Huntington Library Quarterly 78.4 (2015): 595–614. excerpt

- Hirst, Derek. Authority and Conflict: England, 1603–1658 (Harvard UP, 1986).

- Kenyon, J.P. Stuart England (Penguin, 1985), survey

- Kishlansky, Mark A. A Monarchy Transformed: Britain, 1603–1714 (Penguin History of Britain) (1997), standard scholarly survey; excerpt and text search

- Kishlansky, Mark A. and John Morrill. "Charles I (1600–1649)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004; online edn, Oct 2008) accessed 22 Aug 2017 doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5143

- Lockyer, Roger. The Early Stuarts: A Political History of England, 1603–1642 (Addison-Wesley Longman, 1999).

- Lockyer, Roger. Tudor and Stuart Britain: 1485–1714 (3rd ed. 2004), 576 pp excerpt

- Morrill, John. Stuart Britain: A Very Short Introduction (2005) excerpt and text search; 100pp

- Morrill, John, ed. The Oxford illustrated history of Tudor & Stuart Britain (1996) online, a wide-ranging standard scholarly survey.

- Quintrell, Brian. Charles I 1625–1640 (Routledge, 2014).

- Roberts, Clayton and F. David Roberts. A History of England, Volume 1: Prehistory to 1714 (2nd ed. 2013), university textbook.

- Russell, Conrad. "Parliamentary history in perspective, 1604–1629." History 61.201 (1976): 1–27. online

- Scott, Jonathan. England's troubles: seventeenth-century English political instability in European context (Cambridge UP, 2000).

- Sharp, David. The Coming of the Civil War 1603–49 (2000), textbook

- Sharpe, Kevin. The personal rule of Charles I (Yale UP, 1992).

- Sharpe, Kevin, and Peter Lake, eds. Culture and politics in early Stuart England (1993).

- Trevelyan, George Macaulay. England under the Stuarts (1925) online a famous classic.

- Van Duinen, Jared. "'An engine which the world sees nothing of': revealing dissent under Charles I's' personal rule'." Parergon 28.1 (2011): 177–196. online

- Wilson, Charles. England's apprenticeship, 1603–1763 (1967), comprehensive economic and business history.

- Wroughton, John. ed. The Routledge Companion to the Stuart Age, 1603–1714 (2006) excerpt and text search