Jews of Catalonia

Jews of Catalonia (Catalonian Jewry, Catalonian Judaism, in Hebrew: יהדות קטלוניה) is the Jewish community that lived in the Iberian Peninsula, in the Lands of Catalonia, Valencia and Mallorca[1] until the expulsion of 1492. Its splendor was between the 12th to 14th centuries, in which two important Torah centers flourished in Barcelona and Girona. The Catalan Jewish community developed unique characteristics, which included customs, a prayer rite (Nusach Catalonia),[2] and a tradition of its own in issuing legal decisions (Halakhah).[3] Although the Jews of Catalonia had a ritual of prayer[4] and different traditions from those of Sepharad[5], today they are usually included in the Sephardic Jewish community.

Following the riots of 1391 and the expulsion of 1492, Jews who did not convert to Christianity were forced to emigrate to Italy, the Ottoman Empire, the Maghreb, North Africa and the Middle East.[6][7][8]

Early history

Historians affirm that Jews arrived at the Iberian Peninsula before the destruction of the Second Temple, although as regards archaeological remains, the oldest burial gravestones that have been found which testify to the existence of Jewish communities date from the third century.

The term Aspamia derives from the name Hispania and refers to the Iberian Peninsula in Roman times.[9] At the beginning of the 5th century, the Roman domination of the peninsula fell to the Visigoths. During the Visigoth period, numerous decrees were issued against the Jews and sometimes they were forced to convert to Christianity or be expelled.

In 711 CE, Muslims began conquering the Iberian Peninsula. The conquered areas that were under the rule of Islam were called al-Andalus (in Arabic: الأندلس). We do not know much about the history of the Jews at the beginning of Islamic rule, but we are aware that the Jews began to use the term Sepharad[10] to refer to these lands.[11]

In a process of territorial reoccupation called Reconquista, the Christian kingdoms progressively conquered all Islamic territories, from north to south. With the Christian Reconquista, the territories occupied by the kingdoms of Castile and Portugal were also called by the Jews Sepharad, while Catalonia and the other kingdoms of the north were called Edom or named after Esau.[12]

The reconquest of Catalonia began under the auspices of the Frankish kings, who forced the Muslims who had managed to cross the Pyrenees at the Battle of Poitiers in 732 to retreat to the south. All the lands freed from the Islamic domain became counties and remained under the administrative organization of the Franks. The Catalan counties, led by the counts of Barcelona, slowly broke free from the Franks and began to govern themselves independently. Old Catalonia became a zone of containment (Marca Hispanica) against the spread of Islam. Jews often moved from Sepharad (the Muslim zone) to the northern lands (the Christian kingdoms), and vice versa. The fact that many of them spoke Arabic and also the vernacular Romance languages helped them to serve as translators and acquire important positions in both Muslim and Christian governments. Jews owned fields and vineyards and many of them devoted themselves to agriculture.

In this early period, the Jewish scholars of Catalonia who sought advanced Talmudic studies used to go to study in the Talmudic academies (yeshivot) in the South. Also, those who wanted to study science or linguistics went to Sepharad, as did Rabbi Menachem ben Saruq (920-970), who was born in the Catalan city of Tortosa and moved with all his family to Cordoba to study and to devote himself to the Hebrew language under the patronage of Governor Shemuel ibn Nagrella.

The first evidence of an important Jewish settlement in Barcelona and Girona are from the 9th century CE. We know that in the 11th and 12th centuries in Barcelona there was a rabbinical court (Bet Din) and an important teaching center of the Torah. In this period, Barcelona became a link in the chain of transmission of the teachings of the Geonim[13].

Important Catalonian Rabbis from this time are Rabbi Yitzchaq ben Reuven al-Bargeloni (1043 -?), Rabbi Yehudah ben Barzilay ha-Barceloni, called Yehudah ha-Nasi of Barcelona (late 11th century, beginning of the 12th century) and Rabbi Avraham bar Chiyya Nasi[14] (late 11th century, first half of the 12th century). We know that two of the great chachamim of Provence, Rabbi Yitzchaq ben Abba Mari (1122-1193) and Rabbi Avraham ben Rabbi Yitzchaq (1110-1179), moved to Barcelona.

Catalonia joined Provence in 1112 and Aragon in 1137, and thus the County of Barcelona became the capital of the unified realm called the Crown of Aragon. The kings of the Crown of Aragon extended their domains to the Occitan countries.

12th and 13th centuries

In the 12th and 13th centuries the Catalonian Talmudic academies thrived. The great Rabbis and kabbalists Ezra and Azriel bene Shelomoh (late 12th century, beginning of the 13th century) disciples of the famous Rabbi Yitzchaq el Cec (the Blind) (1160-1235), son of Rabbi Avraham ben David (Raabad) of Posquières (1120-1198), stood out in the city of Girona. We can also include Rabbi Yaaqov ben Sheshet (12th century) among the Girona kabbalists of this period. Also, from Girona was Rabbi Avraham ben Yitzchaq he-Hazan (12th-13th centuries) author of the piyyut[15] Achot qetanah (little sister). From the city of Girona was the greatest of Catalonian sages, Rabbi Moshe ben Nachman (Ramban, or Nachmanides) (1194-1270), whose Catalonian name was Bonastruc ça Porta.

Although the city of Girona was an important center of Torah that had a Bet Midrash (House of Study) dedicated to the study of the Kabbalah, the main city was Barcelona, where the Ramban served as the head of the community. During this period, Rabbi Yona Girondi (1210-1263) and his famous disciples Rabbi Aharon ben Yosef ha-Levi of Barcelona (Reah) (1235-1303) and Rabbi Shelomoh ben Adret (Rashba) (1235-1310). Also, Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh) (1250-1327), his son Rabbi Yaaqov ben Asher (Baal ha-Turim) (1269-1343), and Rabbi Yom Tov ben Avraham ha-Sevilli (Ritba) (1250–1330), disciples of Rashba and Reah. We can say that at that time Barcelona became the most important Talmudic study center in all of the European Jewry. It was also during this time that certain Catalan Jewish families occupied key positions in the Catalonian economy, such as the Taroç family of Girona.

In Catalonia in the 13th century Jews were victims of blood libels and were forced to wear a distinctive sign called Rodella. The authorities prohibited Jews from performing public office and were forced to participate in public disputes with representatives of Christianity, such as the Barcelona Disputation of 1263 in which the Ramban participate as a representative of Judaism. The Jews were private property of the monarchy who charged them taxes in exchange for protection.

The kings of the Crown of Aragon expanded the Catalan domains and conquered Mallorca, Valencia, Ibiza and Menorca. In 1258 they signed the Corbeil treaty with the French king for which they renounced to their rights over the Occitan lands. In return, the Franks resigned their demands on the Catalan lands.

14th century

.jpg.webp)

In the 14th century Christian fanaticism prevailed throughout the Iberian Peninsula and there were many persecutions against the Jews. We can mention among Catalonian sages of this period Rabbi Peretz ben Yitzchaq ha-Kohen (1304-1370) who was born in Provence but dwelled in Barcelona, Rabbi Nisim ben Reuven Girondi (Ran) (1315-1376) who served as a Rabbi in Barcelona, Rabbi Chasday ben Yehudah Cresques (the elder), Rabbi Yitzchaq bar Sheshet Perfet (Ribash) (1326-1408), Rabbi Chasday Cresques (Rachaq) (1340-1412), Rabbi Yitzchaq ben Moshe ha-Levi (Profiat Duran, ha-Ephody) (1350-1415), Rabbi Shimon ben Tzemach Duran (Rashbatz) (1361-1444). From this same period, we can include the cartographer of Mallorca Avraham Cresques (14th century) and the poet Shelomoh ben Meshullam de Piera (1310/50-1420/25).

Rabbi Nisim ben Reuven Girondi (Ran) resumed the activity of the Barcelona Yeshivah in the 50s and 60s, after the Jewish community was heavily affected by the Black Death in 1348. In 1370, Jews of Barcelona were victims of attacks instigated by a blood libel; a few Jews were assassinated and the secretaries of the community were imprisoned in the synagogue for a few days without food. Following the succession of John I of Castile, conditions for Jews seem to have improved somewhat. With John I even making legal exemptions for some Jews, such as Abraham David Taroç.

The end of the century brought the revolts of 1391. As a result of the riots, many Jews were forced to convert to Christianity and many others died as martyrs. Others succeeded in fleeing to North Africa (such as Ribash and Rashbatz), Italy and the Ottoman Empire. It was the end of the Jewish communities of Valencia and Barcelona. The community of Mallorca held out until 1435, when Jews were forced to convert to Christianity; the community of Girona barely endured until the expulsion of 1492.

Rabbi Chasday Cresques, in a letter he sent to the Jewish community of Avignon, offers us an account about the riots of 1391.[16] In summary, we can conclude from his account that the riots began on the first day of the Hebrew month of Tammuz (Sunday, 4/6/1391) in Seville, Cordoba, Toledo and close to seventy other locations. From day seven of the month of Av (Sunday, 9/7/1391), they extended to other communities of the Crown of Aragon: Valencia, Barcelona, Lleida, Girona and Mallorca. During the 1391 attacks, the majority of the Jewish communities of Sepharad, Catalonia and Aragon were destroyed.

During the thirteenth, fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, the kings of the Crown of Aragon expanded their territories to the lands of the Mediterranean; they conquered Sicily (1282), Corsica (1297-1516), Athens (1311), Neopatria (1318), Sardinia (1323-1326) and Naples (1435-1442).

15th century

The fifteenth century was very hard for Jewish life in the Iberian Peninsula. The communities that survived the 1391 riots faced great pressure on the part of the church and the Christian population. The kings, who were in a difficult economic situation, imposed heavy taxes on Jewish communities. The lives of the “Converso” Jews who converted to Christianity was not easy either, the church called them “new Christians” and they always kept them under suspicion, since many of them accepted Christianity only as an outward pretense but actually maintained Judaism in secret. The Inquisition persecuted and punished the new Christians who observed the commandments of Judaism.

Catalonia hosted one of the longest disputes in the Middle Ages, the famous Dispute of Tortosa (1413-1414). In the 15th century, we find the poet Shelomoh ben Reuven Bonafed in Catalonia.

In 1469 King Fernando of Aragon (1452-1516) and Queen Isabel of Castile (1451-1504) married and unified the two kingdoms. In 1492 they completed the reconquest with the defeat of the Kingdom of Granada and expelled Jews from all of their kingdoms.

The diaspora of the Jews of Catalonia

The first group of Jews were exiled from Catalonia in the wake of the 1391 attacks; they went mainly to Italy (Sicily, Naples, Rome, Livorno), North Africa (Algeria) and the Ottoman Empire (mainly Salonica, Constantinople and the Land of Israel). The second group were expelled by the Catholic Monarchs. The Edict was decreed on March 31, 1492, and time was given until July 31 for Jews to sell up their property and leave. This date was the eve of the eighth of the month of Av in the Hebrew calendar that year; the expelled Jews were traveling by sea on Tisha B'Av, the 9th of Av, a day on which a number of disasters in Jewish history occurred. A large number of Jews converted to Christianity to be allowed to stay in Catalonia.

Settlement in Italy

Many of the Catalonian Jews arrived in Italy and found refuge in Sicily, Naples, Livorno and the city of Rome.

Sicily

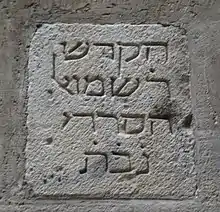

We know that Jews from the Iberian Peninsula settled in Sicily since the 11th century.[17] The famous Kabbalist Rabbi Avraham Abulafia (1240-1291), who studied many years in Catalonia, settled in Sicily, where he wrote most of his works.[18] Sicily had been part of the Catalan-Aragonese crown for many years and the Jewish communities remained on the island until the end of the 15th century, with the expulsion edict of the Jews of the island on June 18, 1492. We know of the existence of a Catalan Jewish community in the island thanks to the identification of a manuscript[19] of the 14th century as siddur nusach Catalonia.[20] In 2017, an old Aron ha-Qodesh (the sacred Ark of the synagogue where the Torah scrolls are stored) was rediscovered in the city of Agira.[21] It was found in the church of Sancta Sanctorum Salvatore and commemorates the construction of the synagogue of the Catalan Jews in 1453, it is one of the oldest Aron ha-Qodesh in Europe.

Rome

Catalonian Jews were also exiled to the city of Rome. In 1517 the Catalonian Jewish community of Rome was well organized and built a synagogue following the minhag[22] Catalonia (Schola hebreorum Nationis Catalanorum).[23] In 1519 Pope Leo X (1475-1521) granted them a permit to widen the community and move the synagogue to a new location, allowed them to remodel and adapt it into a house of prayer according to their rites and customs. By the end of 1527, the Catalonian community and the Aragonese community decided to merge. The joint synagogue of Catalonia and Aragon changed its location again in 1549. In 1555, the community approved the expenses for the construction of another synagogue. The Catalan-Aragonese community fought to avoid merging with the Sephardic communities. All other communities from the Iberian Peninsula merged into a single united Iberian community in Rome, except for the Catalonians who joined the Aragonese. With the establishment of the ghetto in 1555, the Catalonian community maintained its own separate synagogue. In a census of 1868, it can be observed that of the total of 4995 Jews in Rome, 838 belonged to the community of Catalonia. In 1904 the Catalan synagogue ended up joining the other synagogues of Rome to form a single synagogue that was constructed on the banks of the Tiber River. Since then we have no information about the Catalonian community.

Settlement in the Ottoman Empire

The exiled Jews of Catalonia also migrated to the Ottoman Empire where they were organized in communities according to the place of origin that were called Qehalim.[24] There were Catalonian Qehalim in Istanbul, Edirne, Salonica and Safed, among others.[25]

The Catalonian Jewish Community of Salonica

The Jews of Catalonia formed a community in Salonica that was called “Catalan”.[26] Despite being a minority, the Catalonian Jews fought to avoid merging with the Sephardic communities and maintained their ancient customs. The religious leaders of the holy communities of Catalonia in Salonica received the title of Marbitz Torah[27] and not the title Rabbi. The first known was Eliezer ha-Shimoni, who arrived in Salonica in 1492. He had a great influence on all the communities of Salonica and was one of the first to sign the agreements (Haskamot) of the sages. Later we find Moshe Capsali. The chacham Yehudah ben Benveniste, also arrived after the expulsion and established a very important library. Another chacham from the Catalonian Jewish community was Rabbi Moshe Almosnino, Marbitz Torah, exegete and philosopher, son of Barukh Almosnino, who had rebuilt the Catalonian synagogue after the fire of 1545.[28]

In 1515, the community was divided into two Qehalim that were called Catalan yashan (Old Catalan) and Catalan chadash (New Catalan).[29]

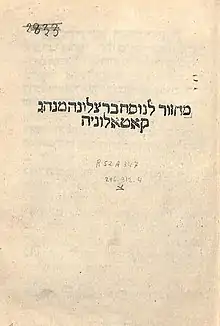

In 1526, the machzor of Yamim Noraim (Days of Awe), known as "Machzor le-nusach Barcelona minhag Catalunya"[31] was first published. According to the colophon, the impression was finished on the eve of Yom Kippur of the year 5287 (1526).[32]

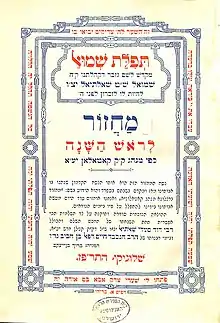

Catalonian Jews published several reprints of the machzor in the nineteenth century. In 1863 they printed an edition titled "Machzor le-Rosh ha-Shana ve-Yom ha-Kippurim ke-minhag qahal qadosh Catalan yashan ve-chadash be-irenu zot Saloniki".[33] This edition was published by Yitschaq Amariliyo.

In 1869 the "Machzor ke-minhag qahal qadosh Catalan yashan ve-chadash" was printed. The editors were: Moshe Yaaqov Ayash and Rabbi Chanokh Pipano, and those who carried out the impression were: David, called Bekhor Yosef Arditi, Seadi Avraham Shealtiel. The machzor was published under the title "Machzor le-Rosh ha-Shana kefi minhag Sepharad ba-qehilot ha-qedoshot Saloniqi" and includes the prayers of the community of Aragon and the communities Catalan yashan ve-chadash.

The Catalonian Jewish community of Salonica existed as such until the Holocaust.[35] In 1927, they published a numbered edition in three volumes of the machzor, entitled "Machzor le-yamim noraïm Kefí Minhag q[ahal] q[adosh] Qatalan, ha-yadua be-shem nusach Bartselona minhag Qatalunya"[36]. In the second volume "Tefillat Yaaqov", there is a long historical introduction about the Jewish community of Catalonia and the edition of the machzor written in Judeo-Spanish;[37] the same summary introduction is found in the first volume "Tefillat Shemuel ", written in Hebrew. Below is a fragment of the translation of the Hebrew version:

«One of the most precious pearls that our ancestors brought from the exile of Catalonia, when they had to leave as exiles, was the old order of the prayers of Rosh ha-Shana and Yom Kippur, known as the 'nusach Barcelona, minhag Catalunya'.

And because of the misfortunes and tumult of the exile, that arrived of fatal form on the poor wandering refugees, the majority of the customs were confused, and slowly, almost all were fused in the same order of prayers called 'nusach Sepharad', almost all, except some exceptional communities that did not change their customs.

The members of the Holy community Catalonia in our city of Salonica did not change their custom, and until today they maintain the tradition of their ancestors and offer their prayers to God on Days of Awe following the ancient nusach that they brought from Catalonia.

The Jews of Catalonia were the most prominent among their brothers in the rest of the Sepharad countries and their wisdom and science were superior. The distinguished communities of Barcelona always took pride in the fact that great Rabbis and personalities from their community illuminated the eyes of the whole Jewish diaspora. There was a saying that Sephardic Jews used to say: the air of Barcelona, it makes you wise. »

The Catalonian Jewish community of Salonica was totally annihilated in the Holocaust. The few survivors emigrated to Israel after the war between the years 1945 and 1947.

Settlement in the central Maghreb

The coasts of Catalonia, Valencia and Mallorca are in front of the coast of the central Maghreb. These lands long maintained commercial relations; also, the Jewish communities maintained close ties. After the riots of 1391, a large group of Catalonian Jews fled to the coasts of the central Maghreb. We know that most of the Jews of Barcelona fled and settled in the city of Algiers. At that time, three kingdoms were established in the Maghreb after the fall of the Almohad, one in the area of present-day Morocco, another in Tunisia and a third in Algeria, which was ruled by the dynasty of Beni-Ziyan from the ancient capital of Tlemcen. In general, the Jews of Castile went to Morocco, while the Jews of Catalonia, Valencia, Mallorca and Aragon went to peesent-day Algeria and Tunisia.

The Jews of Algiers

The Muslim rulers of the central Maghreb received the Jewish exiles with open arms. As soon as the Christian authorities saw that Jews and converts fled to the Maghreb, they forbade them from leaving the country, increased their persecution and flight became more difficult. The Jews who settled in the central Maghreb received the status of dhimmis, as is usual in Islamic countries in exchange for paying taxes. The situation of Jews in the central Maghreb before the arrival of the exiles was very poor, both their economic situation and the level of Torah studies. Peninsular refugees contributed to raising the country's economy thanks to commercial activities with European lands and also improved the level of Torah studies.

Two of the great later Rishonim, Rabbi Yitzhaq bar Sheshet Perfet (Ribash)[39] and Rabbi Shimon ben Tzemacḥ Duran (Rashbatz)[40] fled to the Maghreb. Ribash had long been the grand Rabbi of Catalonia, and Rashbatz, despite his great preparation and knowledge of the Torah, had been dedicated to the medical profession. After a while, Ribash was named Mara de-Atra (maximum rabbinical authority) and head of the Rabbinic Court of the Algiers community, and Rashbatz was appointed Dayan (judge) to his court. When Ribash died, Rashbatz occupied his place. The Jews of the central Maghreb accepted the authority of these two great Rabbis, who were followed by the descendants of Rashbatz, his son Rabbi Shelomo ben Shimon (Rashbash) and his disciples. Throughout the generations, the Jews of the central Maghreb have faithfully and meticulously maintained the spiritual legacy and customs that came from Catalonia. Until today, Ribash, Rashbatz and Rashbash are considered the main Rabbis of Algiers.

One of the characteristics of the manner of dictating halakhah by the Rabbis of Algiers throughout generations has been respect for customs and traditions; the established custom has always trumped halakha, and this is a characteristic that was inherited from Bet Midrash of the Ramban. Matters of halakha in Algiers have always been dictated following the school of Ribash, Rashbatz and Rashbash, and not according to the opinions of Maran ha-Bet Yosef (Yosef Caro, and his work the Shulchan Arukh).[41] In fact, the Jews of Algiers followed the halakhic dictation inherited from the Catalan Bet Midrash of the Ramban and the Rashba. Thus, for example, Rabbi Avraham ibn Taua (1510-1580),[42] grandson of Rashbatz, responded to a question asked by the Rabbis of Fez on a matter referring to the laws of Shabbat:[43]

«Answer: Dear Rabbis, God guard you; know that we are [descendants of] the expelled from the land of Catalonia, and according to what our parents of blessed memory used in those lands, we also used in these places where we have dispersed because of our sins. You know that the Rabbis of Catalonia, according to the dictates on which all the customs of our community are based, are Ramban, Rashba, Reah and Ran, of blessed memory, and other great Rabbis who accompanied them in their generation, although their opinions were not published. Therefore, you do not have to question the customs of our community, since as long as you cannot find any of the issues explicitly mentioned in the books, it should be assumed that they followed the custom according to these great Rabbis. »

Also, regarding the order of prayers and piyyutim, the Jews of Algiers were strictly conservative with the customs that came from Catalonia. Machzor minhag Algiers, for example, arrived from Catalonia around 1391.[44]

In the eighteenth century, scholars questioned some of the ancient customs saying that they contradicted the dictates of Rabbi Yitzchaq Luria Ashkenazi (Arizal) (1534-1572). The old custom that came from Catalonia consisted of reciting piyyutim (and also prayers and supplications) in the middle of prayer. They argued that the custom of the city had to be changed. So, they began to change the nusach of the prayers that had been in force in Algiers since ancient times. The Algerian Rabbis opposed this development, arguing that the old custom could not be changed,[46] but in the following generations, most synagogues in the city of Algiers did change the rite of prayer and adopted the custom of the Arizal (known as the custom of the Kabbalists, minhag ha-mequbalim).[47] Only two synagogues maintained the ancient custom (known as the custom of literalists, minhag ha-pashtamim): The Great Synagogue and the synagogue Yakhin u-Boaz (later renamed Guggenheim Society).

The piyyutim mentioned above, which are recited on special Shabbatot and festivals, etc., were edited in a book called Qrovatz.[48] The Jews from Algiers have maintained the texts and melodies that arrived in Algiers during the period of the Ribash and the Rashbatz until the present day. According to the tradition, these are the original melodies that arrived from Catalonia with the two great Rabbis.[49]

In 2000, the annual Ethnomusicology Workshop was held,[50] which focused on the customs and liturgical tradition of the Jews of Algeria.[51] Algerian cantors from France and Israel attended. The workshop was recorded and today the recordings can be listened to on the website of the National Library of Israel. The liturgy of Shabbat, Rosh Chodesh, Yamim Noraim, festivals, fasts and piyyutim for various celebrations were recorded. Although more than 600 years have elapsed, and there have been certain alterations, we can affirm that the uniqueness of the liturgical tradition of the Jews of Algiers largely preserves the medieval tradition of liturgical songs of the Jews of Catalonia.

Bibliography

- Yitzhak Baer, A history of the Jews in Christian Spain, Philadelphia : Jewish Publication Society of America, 1961–1966.

- Jean Régné, History of the Jews in Aragon: regesta and documents, 1213-1327 Jerusalem: 1978.

- Yom Tov Assis, The Golden Age of Aragonese Jewry. Community and society in the Crown of Aragon, 1213-1327, London: 1997.

- Ariel Toaff, «The jewish communities of Catalonia, Aragon and Castile in 16th century Rome», Ariel Toaff, Simon Schwarzfuchs (eds.), The Mediterranean and the Jews. Banking, Finance and International Trade (XVI-XVIII centuries), Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1989, pp. 259–270.

- Eduard Feliu, «La trama i l'ordit de la historia dels jueus a la Catalunya medieval», I Congrés per a l'estudi dels jueus en territori de llengua catalana. Barcelona: 2001, pp. 9–29.

- Jewish Catalonia: Catalog of the exhibition held in Girona at the Museu d'Història de Catalunya, 2002.; Includes bibliographical references.

- Simon Schwarzfuchs, «La Catalogne et l'invention de Sefarad», Actes del I Congrés per a l'estudi dels jueus en territori de llengua catalana: Barcelona-Girona, del 15 al 17 d'octubre de 2001, Barcelona: Publicacions i Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona, 2004, pp. 185-208.

- A history of Jewish Catalonia : the life and death of Jewish communities in Medieval Catalonia / Sílvia Planas, Manuel Forcano; photography, Josep M. Oliveras. 2009, Includes bibliographical references.

- Manuel Forcano, Els jueus catalans: la historia que mai no t'han explicat, Barcelona: Angle Editorial, 2014.

External links

Footnotes

- See: Yitzhak Baer, A history of the Jews in Christian Spain, Philadelphia : Jewish Publication Society of America, 1961-1966.

- According to Rabbi Yitzhaq Luria Ashkenazi (Arizal), nusach Catalonia is one of the 12 existing nusachim that correspond to the 12 tribes of Israel (Rabbi Chayim Vital, Sefer Shaar ha-Kavanot, nusach ha-tefillah, the secret of the 12 doors). Regarding the different traditions and customs, the Arizal divides the people of Israel into four major families: Sepharad, Ashkenaz, Catalonia and Italy (Sheneh Luchot ha-Berit, Torah she-bikhtav, Bemidbar).

- Rabbi Shimon ben Tzemach Duran (Rashbatz) mentions on several occasions that in Catalonia tradition was ruled according to the opinions of Rabbi Shelomoh ben Adret (Rashba) while in Sepharad was ruled according to the opinions of Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh), Rabbi Yaaqov ben Asher (Baal ha-Turim) and Rabbi Moshe ben Maymon (Rambam): «In Catalonia the halachic decisions are followed according to Rashba, while in Sepharad are followed according to Baal ha-Turim and Rambam» (reference: Tashbetz, vol 3, 257, see also: Tashbetz vol 2, 141, vol 3, 86, vol 3, 118, vol 4, column 3, 10).

- Recently, has been published the Sidur Catalunya, which constitutes the first reconstruction of the old nusach Catalonia. The siddur is based on six medieval Hebrew manuscripts (from the 14th to the 16th century) and also includes a series of commentaries, laws and customs that were compiled by a disciple of Rabbi Yona Girondi at the Talmudic academy of Barcelona.

- In the halakhic and Responsa literature of the Rishonim, a clear distinction between Sepharad and Catalonia is made, both in terms of customs as regards the rites of prayer. See: Responsa of Rabbi Avraham ben David (Raabad) 131, Responsa of Rabbi Shelomoh ben Adret (Rashba) new 345, Responsa of Rabbi Yitzchaq bar Sheshet (Ribash), 79, 369. Responsa of Rabbi Shimon ben Tzemach Duran (Rashbatz), Tashbetz vol. 3, 118; vol. 4 (Chut ha-Meshulash), column 3, 10; vol 3, 257; vol. 2, 141, vol. 3, 86, vol. 3, 118, vol. 4, column 3, 10. For more information about the differences between the customs of Catalonia and Sepharad see: Aharon Gabbai, «Hanachat Tefillin be-chol ha-moed». Haotzar 16 (5778), pp. 366-379 (in Hebrew). Aharon Gabbai, «Nusach chatimat birkat ha-erusin», Moriah year 36, 1-2 (5778), pp. 349-369 (in Hebrew).

- Ray, Jonathan (2013). After Expulsion: 1492 and the Making of Sephardic Jewry. NYU Press. ISBN 9780814729113.

- "Ottoman Empire welcomed Jews exiled from Spain".

- "Spain announces it will expel all Jews".

- Third century BCE - 5th century CE.

- The name Sepharad appears for the first time in the book of Obadiah 1:20: «And this exiled host of the children of Israel who are [with] the Canaanites as far as Zarephath and the exile of Jerusalem which is in Sepharad shall inherit the cities of the southland». Rashi was based on the Targum Yonathan, which translated the name Sepharad by the term Aspamia: «Sepharad, translated Yonathan: Aspamia».

- From the letter of Rabbi Chasday ibn Shaprut to the King of the Kuzarim, we can deduce that the name Sepharad referred to the lands that were under the rule of Islam, that is, al-Andalus: «Know your majesty the King, that the name of our land in which we live, in the sacred language is Sepharad and in the language of the Ishmaelites (Arabs) that inhabit it is al-Andalus, and the name of its capital is Cordoba». The letter was written by Rabbi Yehudah ha-Levi, and therefore, the sentence only reflects the time of the author.

- So, Rabbi Moshe ben Maymon (Maimonides) writes in his book Mishneh Torah: «Synagogues and study houses must be treated with respect and must be sprinkled (cleaned up). In Sepharad and in the West (Morocco), in Babylon and in the Holy Land, it is customary to light the candles in the synagogues and extend the blinds on the floor on which the parishioners sit. In the lands of Edom (Christian lands) in the synagogues people sit on chairs [or benches]». (Hilkhot Tefillah, 11, 5).

- The period of the Gueonim dates from the end of the 6th century to the middle of the 11th century.

- Barcelona was well-known like the city of the nesiim (patriarchs), due to the great amount of personalities that enjoyed this honorific title.

- Liturgical poem.

- The letter was published in the book Shevet Yehudah, Rabbi Yehudah ibn Verga (edition of Hanover, 1924).

- In some manuscripts preserved in the Cairo Genizah, we find Jews called the 'Sephardic' or the 'Andalusi'. See: Menahem ben Sassoon, Yehude Sicilia, teudot u-meqorot, Jerusalem: 1991 (in Hebrew).

- Moshe Idel, «The Ecstatic Kabbalah of Abraham Abulafia in Sicily and its Transmission during the Renaissance», Italia Judaica V: Atti del V Convegno internazionale (Palermo, 15-19 giugno 1992), Roma: Ministerio per i benni culturali e ambientali, pp. 330-340.

- In Sidur Catalunya, the manuscript Parma Palatina 1750 is identified as nusach Catalonia. Before the reading of the Torah of Shabbat there appears the "blessing of the king" in which King Don Fadrique of Aragon is mentioned, surely it is King Fadrique III (1341-1377) who reigned in Sicily during 1355-1377. This manuscript represents the first document that refers to the Catalan Jewish community of Sicily, which as we can see already existed before the 1391 revolts.

- Until today, it was supposed that the migratory wave of Catalan Jews in Sicily began as a result of the 1391 revolts. See: Nadia Zeldes, «Els jueus i conversos catalans a Sicília: migració, relacions culturals i conflicte social», Roser Salicrú i Lluch et al. (eds.), Els catalans a la Mediterrània medieval: noves fonts, recerques i perspectives, Barcelona: Institut de Recerca en Cultures Medievals, Facultat de Geografia i Història, Universitat de Barcelona, 2015, pp. 455-466.

- See: Ariela Piatelli, «Gli ebrei catalani nella Sicilia del ’400. In un armadio di pietra la loro storia», La Stampa (13 setembre 2017).

- Tradition, custom.

- The archive documents were published in: Ariel Toaff, «The jewish communities of Catalonia, Aragon and Castile in 16th century Rome», Ariel Toaff, Simon Schwarzfuchs (eds.), The Mediterranean and the Jews. Banking, Finance and International Trade (XVI-XVIII centuries), Ramat Gan: Bar-Ilan University Press, 1989, pp. 259-270.

- They were organized in seven Qehalim called: Catalan, Aragon, Castilla, Lisbon, Guerush Sepharad, Mallorca and Sicily.

- The censuses were published in: Simon Schwarzfuchs, «La Catalogne et l'invention de Sepharad», Actes del I Congrés per a l'estudi dels jueus en territori de llengua catalana: Barcelona-Girona, del 15 al 17 d'octubre de 2001, Barcelona: Publicacions i Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona, 2004, pp. 185-208.

- The cemetery of the Jewish community of Salonica was established in the 16th century and was destroyed in 1943. Nowadays, the University of Salonica is in the same place. Although the tombstones were destroyed some local researchers transcribed the inscriptions, so the text of the funeral tombstones of the Catalan community has been preserved.

- Torah teacher, religious community leader.

- In the Responsa of Rabbi Samuel de Medina, he ruled in favor of Moshe Almosnino in order to build a Synagogue of the holy community of Catalonia.

- We find witnesses of this division in the Responsa of Rabbi David Ben Zimra (Radbaz), first part, 292.

- National Library of Israel R 52 A 347.

- Machzor according to the rites of Barcelona and the custom of Catalonia.

- In the Responsa of rabbi, Shelomoh ben Avraham ha-Kohen (Maharshakh) mentions the "machzor le-yamim noraim be-nusach qahal qadoix Catalan".

- Machzor for Rosh ha-Shana and Yom Kippur according to the custom of the old and new Catalan community of our city of Salonica.

- National Library of Israel R 41 A 257.

- Yitzchaq Shemuel Immanuel, Guedole Salonica le-dorotam, Tel Aviv: 1936 (it includes lists with the surnames of the communities Catalan yashan and Catalan chadash).

- First volume: «Tefillat Shemuel. Machzor le-Rosh ha-Shana»; second volume: «Tefillat Yaaqov. Machzor le-Shacharit ve-Musaf Yom Kippur»; third volume: «Tefillat Seadi. Machzor leil Kippur u-Mincha u-neila».

- The Sephardic community (Castile) became the largest and most influential in Salonica, which was how the Judeo-Spanish language (also called Ladino, Judezmo, Spañolit, etc.) became the lingua franca of all Jewish communities (including those of Catalonia, France and Ashkenaz).

- National Library of Israel R 56 A 346.

- The Ribash was for many years the great Rabbi of Catalonia.

- The Rashbatz, had been dedicated in Mallorca to the medical profession. Once in the Maghreb, where there was not so much demand for this profession, he was forced to earn a living as a rabbi. (Maguen Avot, chap. 4, 45).

- For example, Rabbi Refael Yedidya Shelomo Tzror (1682-1729), author of the work 'Pri Tzadiq', wrote in his introduction to the Taixbetz book: «In Algiers the local custom is followed, and legal decisions are not issued according to the Bet Yosef ».

- Rabbi Avraham ibn Taua was a descendant of the Rashabtz, and at the same time of the Ramban, and served as the head of the Algerian Yeshivah. His Responsa were compiled in two books, one of which was published in the third part of the book 'Chut ha-meshulash', and that the printers added to the fourth volume of the 'Tashbetz' Responsa book.

- Tashbetz, vol. 4 ('Chut ha-meshulash'), 3, 10.

- Rabbi Yitzchaq Morali (1867-1952), in his introduction to machzor minhag Alger, writes: "This machzor was brought by our Sepharad parents when they fled from the ravages of 1391, and our Rabbis Ribash and Rashbatz, of holy and blessed memory, kept it. And thus, accustomed the later generations».

- National Library of Israel R 23 V 2883.

- See: Shelomo Ouaknin, «Teshuvot chakhme Algir ve-Tunis be-inyan shinui be-minhag ha-tefillah be-Algir», Mekabtziel 39, pp. 33-102 (in Hebrew).

- Minhag ha-mequbalim was established around 1765.

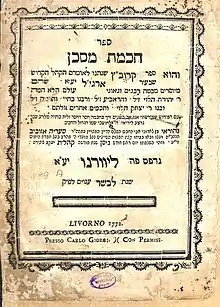

- Nehoray ben Seadya Azoviv, 'Chokhmat Miskén: ve-hu sefer Qrovatz she-nahagu leomram ha-qahal ha-qadosh she-be-ir Argel', Livorno 1772.

- In the synagogues where minhag ha-mequbalim was imposed, they also maintained the melodies and nusach of piyyutim, although they were told outside the tefillah (amidah) and the blessings of the Shema reading, as is nowadays accustomed to the minhag of the Sephardim.

- The workshop was organized by the faculty of music of the University of Bar-Illan with the collaboration of the phonotheque of the National Library of Israel and the Jewish Music Research Center of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Edwin Seroussi & Eric Karsenti, «The Study of Liturgical Music of Algerian Jewry». Pe’amim 91 (2002), pp. 31-50.