Cauda equina syndrome

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a condition that occurs when the bundle of nerves below the end of the spinal cord known as the cauda equina is damaged.[2] Signs and symptoms include low back pain, pain that radiates down the leg, numbness around the anus, and loss of bowel or bladder control.[1] Onset may be rapid or gradual.[1]

| Cauda equina syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

| The cauda equina is the "horse tail" of nerves that branch off after the conus medullaris | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery, orthopedics |

| Symptoms | Low back pain, pain that radiates down the leg, numbness around the anus, loss of bowel or bladder control[1] |

| Usual onset | Rapid or gradual[1] |

| Causes | Disc herniation, spinal stenosis, cancer, trauma, epidural abscess, epidural hematoma[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method | Medical imaging (MRI, CT scan)[1][3] |

| Treatment | Surgery (laminectomy)[1] |

| Prognosis | 20% risk of poor outcome |

| Frequency | 1 in 500,000 a year |

The cause is usually a disc herniation in the lower region of the back.[1] Other causes include spinal stenosis, cancer, trauma, epidural abscess, and epidural hematoma.[1][2] The diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms and confirmed by medical imaging such as MRI or CT scan.[1][3]

CES is generally treated surgically via laminectomy.[1] Sudden onset is regarded as a medical emergency requiring prompt surgical decompression, with delay causing permanent loss of function.[4] Permanent bladder problems, sexual dysfunction or numbness may occur despite surgery.[1][3] A poor outcome occurs in about 20% of people despite treatment.[1] About 1 in 70,000 people is affected every year.[1] It was first described in 1934.[5]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of cauda equina syndrome include:

- Severe back pain

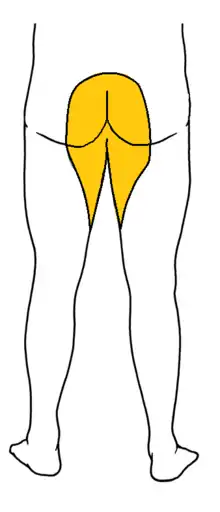

- Saddle anesthesia (see diagram), i.e., anesthesia or paraesthesia involving S3 to S5 dermatomes,[6]: 26 including the perineum, external genitalia and anus; or more descriptively, numbness or "pins-and-needles" sensations of the groin and inner thighs which would contact a saddle when riding a horse.

- Bladder and bowel dysfunction,[7]: 216 caused by decreased tone of the urinary and anal sphincters. Detrusor weaknesses causing urinary retention and post-void residual incontinence as assessed by bladder scanning the patient after the patient has urinated.

- Sciatica-type pain on one side or both sides, although pain may be wholly absent

- Weakness of the muscles of the lower legs (often paraplegia)

- Achilles (ankle) reflex absent on both sides.[7]: 216

- Sexual dysfunction

- Absent anal reflex and bulbocavernosus reflex

- Gait disturbance

Severe back pain, saddle anesthesia, urinary or fecal incontinence and sexual dysfunction are considered "red flags", i.e. features which require urgent investigation.[8]

Causes

After the conus medullaris (near lumbar vertebral levels 1 (L1) and 2 (L2), occasionally lower), the spinal canal contains a bundle of nerve fibers (the cauda equina or "horse-tail") that branches off the lower end of the spinal cord and contains the nerve roots from L1–L5 and S1–S5. The nerve roots from L4–S4 join in the sacral plexus which affects the sciatic nerve, which travels caudally (toward the feet). Compression, trauma or other damage to this region of the spinal canal can result in cauda equina syndrome.

The symptoms may also appear as a temporary side-effect of a sacral extra-dural injection.[9]

Trauma

Direct trauma can also cause cauda equina syndrome. Most common causes include as a complication of lumbar punctures, burst fractures resulting in posterior migration of fragments of the vertebral body, severe disc herniations, spinal anaesthesia involving trauma from catheters and high local anaesthetic concentrations around the cauda equina, penetrating trauma such as knife wounds or ballistic trauma.[10] Cauda equina syndrome may also be caused by blunt trauma suffered in an event such as a car accident or fall.[11]

Spinal stenosis

CES can be caused by lumbar spinal stenosis, which is when the diameter of the spinal canal narrows. This could be the result of a degenerative process of the spine (such as osteoarthritis) or a developmental defect which is present at birth. In the most severe cases of spondylolisthesis cauda equina syndrome can result.[10]

Inflammatory conditions

Chronic spinal inflammatory conditions such as Paget disease, neurosarcoidosis, chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, ankylosing spondylitis, rheumatoid disease of the spine, and chronic tuberculosis can cause it. This is due to the spinal canal narrowing that these kinds of syndromes can produce.[10]

Risk factors

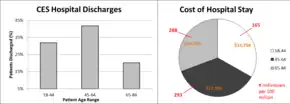

Individuals most at risk for disc herniation are the most likely to develop CES. Race has little influence with the notable exception that African Americans appear slightly less likely to develop CES than other groups.[12][13][14] Middle age also appears to be a notable risk factor, as those populations are more likely to develop a herniated disc; heavy lifting can also be inferred as a risk factor for CES.[12][14]

Other risk factors include obesity and being female.[15]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is first suspected clinically based on history and physical exam and usually confirmed by an MRI scan or CT scan, depending on availability.[4] Bladder scanning and loss of catheter sensation can also be used to evaluate bladder dysfunction in suspected cases of cauda equina syndrome and can aid diagnosis before MRI scanning. Early surgery in acute onset of severe cases has been reported to be important.[4]

Prevention

Early diagnosis of cauda equina syndrome can allow for preventive treatment. Signs that allow early diagnosis include changes in bowel and bladder function and loss of feeling in groin.[16] Changes in sensation can start as pins and needles leading to numbness. Changes in bladder function may be changes to stream or inability to fully empty the bladder. If a person progresses to full retention intervention is less likely to be successful.

Management

The management of true cauda equina syndrome frequently involves surgical decompression. When cauda equina syndrome is caused by a herniated disk early surgical decompression is recommended.[17]

Sudden onset cauda equina syndrome is regarded as a medical/surgical emergency.[4] Surgical decompression by means of laminectomy or other approaches may be undertaken within 6,[18] 24[19] or 48 hours of symptoms developing if a compressive lesion (e.g., ruptured disc, epidural abscess, tumor or hematoma) is demonstrated. Early treatment may significantly improve the chance that long-term neurological damage will be avoided.[17][19]

Surgery may be required to remove blood, bone fragments, a tumor or tumors, a herniated disc or an abnormal bone growth. If the tumor cannot be removed surgically and is malignant then radiotherapy may be used as an alternative to relieve pressure. Chemotherapy can also be used for spinal neoplasms. If the syndrome is due to an inflammatory condition e.g., ankylosing spondylitis, anti-inflammatory, including steroids can be used as an effective treatment. If a bacterial infection is the cause then an appropriate course of antibiotics can be used to treat it.[20]

Cauda equina syndrome can occur during pregnancy due to lumbar disc herniation. The risk of cauda equina syndrome during pregnancy increases with age of the mother. Surgery can still be performed and pregnancy does not adversely affect treatment. Treatment for those with cauda equina can and should be carried out at any time during pregnancy.[21]

Lifestyle issues may need to be addressed post-treatment. Issues could include the person's need for physiotherapy and occupational therapy due to lower limb dysfunction. Obesity might also need to be tackled.[20]

Bowel and bladder control

Rehabilitation of CES depends on the severity of the injury. If permanent damage occurs, then impairment in bladder and bowel control may result.[22] Once surgery is performed, resting is required until the bladder and bowel dysfunction can be assessed. Urinary catheterization may help with bladder control. Gravity and exercise can help control bowel movement (Hodges, 2004). Pelvic floor exercises assist in controlling bowel movements (Pelvic Floor Exercises, 2010). These exercises can be done standing, lying, or on all fours with the knees slightly separated. Full recovery of bowel and bladder control can take as long as two years.

Prognosis

The prognosis for complete recovery is dependent upon many factors. The most important of these is the severity and duration of compression upon the damaged nerve(s). Generally, the longer the time before intervention to remove the compression causing nerve damage, the greater the damage caused to the nerve(s).

Damage can be so severe that nerve regrowth is impossible, and the nerve damage will be permanent. In cases where the nerve has been damaged but is still capable of regrowth, recovery time is widely variable. Surgical intervention with decompression of the cauda equina can assist recovery. Delayed or severe nerve damage can mean up to several years' recovery time because nerve growth is exceptionally slow.

Review of the literature indicates that around 50–70% of patients have urinary retention (CES-R) on presentation with 30–50% having an incomplete syndrome (CES-I). The latter group, especially if the history is less than a few days, usually requires emergency MRI to confirm the diagnosis followed by prompt decompression. CES-I with its more favourable prognosis may become CES-R at a later stage.[23]

Epidemiology

Various etiologies of CES include fractures, abscesses, hematomas, and any compression of the relevant nerve roots.[24] Injuries to the thoracolumbar spine will not necessarily result in a clinical diagnosis of CES, but in all such cases it is necessary to consider. Few epidemiological studies of CES have been done in the United States, owing to difficulties such as amassing sufficient cases as well as defining the affected population, therefore this is an area deserving of additional scrutiny.[12]

Traumatic spinal cord injuries occur in approximately 40 people per million annually in the United States, resulting from traumas due to motor vehicle accidents, sporting injuries, falls, and other factors.[13] An estimated 10 to 25% of vertebral fractures will result in injury to the spinal cord.[13] Thorough physical examinations are required, as 5 to 15% of trauma patients have fractures that initially go undiagnosed.[25]

The most frequent injuries of the thoracolumbar region are to the conus medullaris and the cauda equina, particularly between T12 and L2.[13] Of these two syndromes, CES is the more common.[13] CES mainly affects middle-aged individuals, particularly those in their forties and fifties, and presents more often in men.[13][14][26] It is not a typical diagnosis, developing in only 4 to 7 out of every 10,000 to 100,000 patients, and is more likely to occur proximally.[12][13][14] Disc herniation is reportedly the most common cause of CES, and it is thought that 1 to 2% of all surgical disc herniation cases result in CES.[12][13]

CES is often concurrent with congenital or degenerative diseases and represents a high cost of care to those admitted to the hospital for surgery.[13][26] Hospital stays generally last 4 to 5 days, and cost an average of $100,000 to $150,000.[26] Delays in care for cauda equina results in the English NHS paying about £23 million a year in compensation.[27]

In animals

Degenerative lumbosacral stenosis (DLSS), also known as cauda equina syndrome, is a pathologic degeneration in the lumbosacral disk in dogs. DLSS affects the articulation, nerve progression, and tissue and joint connections of the disk.[28][29] This degeneration causes compressions in soft tissues and nerve root locations in the caudal area of the medulla, causing neuropathic pain in the lumbar vertebrae.[30][31]

References

- Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T (May 2011). "Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position". European Spine Journal. 20 (5): 690–7. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1668-3. PMC 3082683. PMID 21193933.

- "Cauda equina syndrome". Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD). 2015. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- "Cauda Equina Syndrome-OrthoInfo – AAOS". orthoinfo.aaos.org. March 2014. Retrieved 9 November 2017.

- Shapiro S (February 2000). "Medical realities of cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation". Spine. 25 (3): 348–51, discussion 352. doi:10.1097/00007632-200002010-00015. PMID 10703108. S2CID 44975909.

- Chau AM, Xu LL, Pelzer NR, Gragnaniello C (2014). "Timing of surgical intervention in cauda equina syndrome: a systematic critical review". World Neurosurgery. 81 (3–4): 640–50. doi:10.1016/j.wneu.2013.11.007. PMID 24240024.

- Larner AJ (2006). A Dictionary of Neurological Signs (2nd ed.). [New York]: Springer Science+Business Media, Inc. ISBN 9780387262147.

- Kraemer (2009). Intervertebral disk diseases causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prophylaxis (3rd ed.). Stuttgart: Thieme. ISBN 9783131495617.

- Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T (May 2011). "Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position". European Spine Journal. 20 (5): 690–7. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1668-3. PMC 3082683. PMID 21193933.

- Gerald L Burke, MD. "Backache from Occiput to Coccyx". Retrieved 2014-07-23.

- Eck JC (11 May 2007). "Cauda Equina Syndrome Causes". Cauda Equina Syndrome. WebMD. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- Brian (2021-10-12). "What Is Cauda Equina Syndrome?". Retrieved 2023-01-05.

- Schoenfeld AJ, Bader JO (September 2012). "Cauda equina syndrome: an analysis of incidence rates and risk factors among a closed North American military population". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 114 (7): 947–50. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2012.02.012. PMID 22402198. S2CID 2629460.

- Radcliff KE, Kepler CK, Delasotta LA, Rihn JA, Harrop JS, Hilibrand AS, et al. (September 2011). "Current management review of thoracolumbar cord syndromes". The Spine Journal. 11 (9): 884–92. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2011.07.022. PMID 21889419.

- Small SA, Perron AD, Brady WJ (March 2005). "Orthopedic pitfalls: cauda equina syndrome". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 23 (2): 159–63. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2004.03.006. PMID 15765336.

- Long B, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M (January 2020). "Evaluation and management of cauda equina syndrome in the emergency department". The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 38 (1): 143–148. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2019.158402. PMID 31471075.

- Eck JC (11 May 2007). "Prevention". Cauda Equina Syndrome. WebMD. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- Ahn UM, Ahn NU, Buchowski JM, Garrett ES, Sieber AN, Kostuik JP (June 2000). "Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation: a meta-analysis of surgical outcomes". Spine. 25 (12): 1515–22. doi:10.1097/00007632-200006150-00010. PMID 10851100. S2CID 46674147.

- "Neurosurgery for Cauda Equina Syndrome". Medscape. November 11, 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- "Delayed presentation of cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation: functional outcomes and health-related quality of life". Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. July 10, 2001. Archived from the original on 21 March 2015. Retrieved 18 March 2015.

- Tidy C (16 Nov 2009). "Cauda Equina Syndrome". Egton Medical Information Systems. Retrieved 11 January 2010.

- Brown MD, Levi AD (February 2001). "Surgery for lumbar disc herniation during pregnancy". Spine. 26 (4): 440–3. doi:10.1097/00007632-200102150-00022. PMID 11224893. S2CID 31698755.

- "Cauda Equina". Cauda equina - Bladder and Bowel Community. Bladder and Bowel Support Company Limited. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 15 January 2017.

- Gardner A, Gardner E, Morley T (May 2011). "Cauda equina syndrome: a review of the current clinical and medico-legal position". European Spine Journal. 20 (5): 690–7. doi:10.1007/s00586-010-1668-3. PMC 3082683. PMID 21193933.

- Gitelman A, Hishmeh S, Morelli BN, Joseph SA, Casden A, Kuflik P, et al. (November 2008). "Cauda equina syndrome: a comprehensive review". American Journal of Orthopedics. 37 (11): 556–62. PMID 19104682.

- Harrop JS, Hunt GE, Vaccaro AR (June 2004). "Conus medullaris and cauda equina syndrome as a result of traumatic injuries: management principles". Neurosurgical Focus. 16 (6): e4. doi:10.3171/foc.2004.16.6.4. PMID 15202874.

- "National and regional estimates on hospital use for all patients from the HCUP nationwide inpatient sample (NIS)". United States Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research. 2012. Archived from the original on 2015-03-01. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- "Delayed spinal surgery costs £23m in compensation". Health Service Journal. 30 January 2019. Retrieved 5 March 2019.

- Danielsson F, Sjöström L (1999). "Surgical treatment of degenerative lumbosacral stenosis in dogs". Veterinary Surgery. 28 (2): 91–8. doi:10.1053/jvet.1999.0091. PMID 10100762.

- Jeffery ND, Barker A, Harcourt-Brown T (July 2014). "What progress has been made in the understanding and treatment of degenerative lumbosacral stenosis in dogs during the past 30 years?". Veterinary Journal. 201 (1): 9–14. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.04.018. PMID 24878265.

- Giudice E, Crinò C, Barillaro G, Crupi R, Macrì F, Viganò F, Di Pietro S (2019-09-01). "Clinical findings in degenerative lumbosacral stenosis in ten dogs—A pilot study on the analgesic activity of tramadol and gabapentin". Journal of Veterinary Behavior. 33: 7–15. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2019.05.004. ISSN 1558-7878. S2CID 181851509.

- Meij BP, Bergknut N (September 2010). "Degenerative lumbosacral stenosis in dogs". The Veterinary Clinics of North America. Small Animal Practice. 40 (5): 983–1009. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2010.05.006. PMID 20732601.

External links

- 06-093c. at Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy Home Edition