Cavaedium

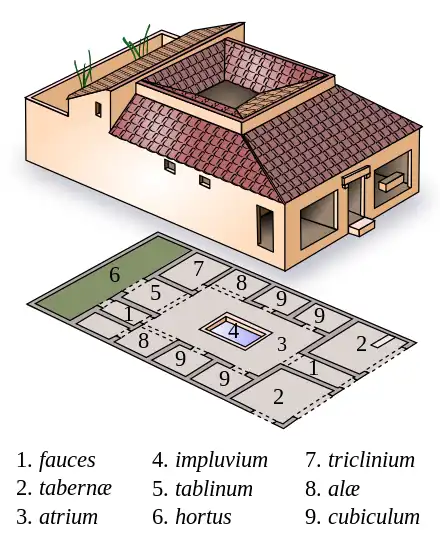

Cavaedium or atrium are Latin names for the principal room of an Ancient Roman house, which usually had a central opening in the roof (compluvium) and a rainwater pool (impluvium) beneath it. The cavaedium passively collected, filtered, stored, and cooled rainwater. It also daylit, passively cooled and passively ventilated the house.

The atrium was the most important room of the Ancient Roman house. The main entrance led into it; patrones received their clientes there, and marriages, funerals, and other ceremonies were conducted there. In earlier and more modest homes, the atrium was the common room used for most household activities; in richer homes, it became mainly a reception room, with private life moving deeper into the (larger) house. The atrium was generally the most elaborate room, with the finest finishings, wall paintings, and furnishings.

The atrium was entered either through a shop[2] or by a straight, narrow passage from the street. The smaller, open room behind the atrium was the tablinum, usually the study of the master of the house. Behind it was a garden; temperature differences between the atrium and the garden drove a draft through the tablinum, making it the coolest room in the house. Unless curtains or movable partitions of the tablinum were closed, a visitor in the passage could see through the atrium and tablinum into the garden; care was taken to make this view impressive. Ideally, rooms off the atrium were arranged symmetrically, or at least to give the impression of symmetry. Bedrooms (cubiculi) and alae (the "wings" of the atrium, alcoves separated by a lintel but not a wall) typically opened off the sides of the atrium.

Small rural Roman buildings did not need atria; they were lit by windows and drew water from wells or watercourses. An urban house (domus), on the other hand, had to be built on a small, narrow lot, as urban land was expensive and street frontage was even more expensive. Theft was also a concern. Urban houses thus came to look inwards onto cortiles, enclosed courts, and light and water were brought in from above. Sometimes urban houses retained a walled garden at the rear, which later often became a peristyle, a sort of cloister surrounded by rooms. Large rural properties were sometimes built around large enclosed farmyards, but the Roman villa or country seat mimicked the city residence from which the wealthy owner generally came, and often had an atrium (or several). In later Roman history the atrium was sometimes also replaced by a peristyle, and rain-gathering with piped water from an aqueduct. The urban houses of poorer Romans might lack atriums entirely; but from (mainly Pompeiian) survey data, atriums, peristyles, or both are found in almost all Roman homes over 350 square meters in size, most over 170 square meters, and some over 50 square meters.[3]

Etymology

The etymology of "cavaedium", "cavum aedium", and "atrium" is debated.[4]

These terms are thought by many to be synonymous;[5][4] others have argued that one term includes the impluvium and the other does not, but are not agreed upon which.[4]

Varro gives classical etymologies: "The hollow of the house (cavum ædium) is a covered place within the walls, left open to the common use of all. It is called Tuscan, from the Tuscans, after the Romans began to imitate their cavædium. The word atrium is derived from the Atriates, a people of Tuscany, from whom the pattern of it was taken."[5] For more modern etymologies, see Wiktionary:atrium.

Uses

Light, water, air and cooling

_WLM_013.JPG.webp)

Roman townhouses rarely had windows, as they often had very little exterior wall. Where present, windows were placed above eye-level, and they were small[4] and contained clathri, window lattices.[4] The compluvium provided most or all of the light to the atrium, its alae, and the adjacent cubiculums. The doorways of the cubicli were usually arranged to maximize the light, and when present, the alae were often needed to let light into the rooms flanking the tablinum.

Traditionally, the atrium collected rainwater. Most atria had compluvium roofs, which sloped inwards towards the hole in the center of the roof; these shed rain water into the impluvium (pool) underneath (the impluvium was usually the same size and shape as the compluvium hole). The water in the impluvium then slowly seeped through the porous bottom of the impluvium into a water storage cistern below. Water for household use could be drawn up in buckets via the puteal (a lidded cylinder set over a hole in the top of the cistern as a wellhead).

In dry weather, water drawn from the cistern could be thrown into the impluvium to evaporatively cool the cistern and the house, and drive a draft. In wet weather, impluvium overflow would generally run out the front door into the street, which was much lower than the interior floor.

The atrium might also contain a fountain, which piped in drinking water from an aqueduct (riverwater and well water was preferred for drinking).[5] Reliable piped water made the rain-collecting function dispensable, and Late-Empire domi often replace atria with peristyle gardens, which could also be made larger.

Ceremonial uses

After a birth, a bed for Juno and a table for Hercules were set up in the atrium.[6] The tollere liberum (ceremony for a newborn), dedication of the bulla at Liberalia (coming-of-age, male), and confarreatio marriage were described as conducted in the atrium, in front of the lararium.

The wedding couch or bed, the lectus genialis, was placed in the atrium, on the side opposite the door or in one of the alae.[4][7] The lectus funebris, or funeral couch, was placed in the atrium, and the body of the deceased was laid in state upon it with feet facing the door.[7]

Everyday uses

The cavaedium was a communal space. Varro says it is "left open to the common use of all".[5] Vitruvius describes it as a room which "any of the people have a perfect right to enter, even without an invitation".[8] It was thus a sort of living-room. Spinning and weaving, major household tasks, were traditionally done in the atrium,[4] as were other domestic occupations.[5] Toys, flutes, writing materials, cutlery, and crockery have all been found in atria.[2]

Historically, the atrium was probably used for cooking, with the compluvium serving as a smoke-hole. This probably continued in poorer households, but richer ones developed a separate kitchen. Similarly, historically the household slept in the cubicles opening off the atrium, but as townhouses became deeper family tended to live deeper in the house, and these became guest rooms (unless the house has dedicated guest rooms, a hospitium).[4] Slaves and servants might sleep in the entrance to their master's cubiculum.

Richer Romans received visitors in the mornings,[4] as their clientes gathered in the atrium for the salutatio. The patron often greeted them from the tablinum.[9] The atrium was generally the most elaborate room,[5] with the finest artworks,[9] wall paintings, imported marble wall-linings, and marble or mosaic floors (mosaics being even more expensive than imported marble slabs).[5] The homes of the richest Romans became more ostentatious as increasing wealth inequality increased housing inequality, and as it became less socially important to display frugalitas and abundentia, and more important to display tryphé.

This patron-class use as a reception-room made the atrium a semi-public space,[4] and it came to be known as the pars urbanan, the city part of the house. The more private space behind the tablinum was the pars rusticana, the rural part.[10] The pars rusticana was centered around a peristyle; it did not exist in early Roman houses. Greek culture was high-status in Roman culture (see Hellenization). The peristyle was borrowed from Greek architecture and became popular, eventually sometimes replacing the atrium.[2] As a result, the names for the pars urbanan are in Latin, while the names for the pars rusticana are Greek loan-words.[11] In the countryside the order was sometimes reversed; the pars urbana cortile which one entered from the main street entrance was a peristyle. The atrium was then buried in the depths of the house, often near a portico (an outwards-looking colonnade on one or more outside walls) with a view of the landscape.[2][12]

Contents

Brazier, a foculus or portable hearth, found in an atrium or other court. Richer households had a separate kitchen.

Brazier, a foculus or portable hearth, found in an atrium or other court. Richer households had a separate kitchen._01.jpg.webp)

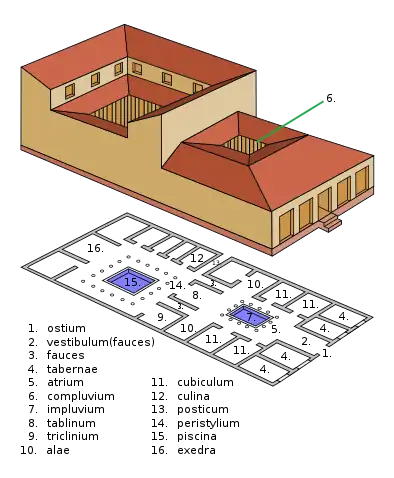

Cast of a bust of Lucius Caecilius Jucundus, found in his atrium in Pompeii.

Cast of a bust of Lucius Caecilius Jucundus, found in his atrium in Pompeii.

Larariums varied in style

Larariums varied in style

The atrium often contained a small chapel to the ancestral spirits (lararium). The household safe (arca) was also kept in the atrium; it contained family treasures and important documents.[9] The room might contain portraits of ancestors, or a bust of the master of the house. In wealthier houses, furniture included an oblong marble cartibulum (table), supported by trapezophoros pedestals depicting mythological creatures like winged griffins.[13] A puteal, a low cylindrical covered wellhead through which water could be drawn from the cistern below, was often present. There would also be works of art, especially statuary, which was set beside the impluvium, on tables, in niches, on walls. etc.[9][4] For night, there might be oil-lamp-stands.[9]

Curtains or partitions might close off the tablinum; alae might also have been curtained at times. Interior doorways might have doors or curtains.

Compluvium

The roof is framed so as to leave an open space in the center, known as the compluvium. The rain from the roof was usually collected in gutters around the compluvium, and discharged thence into the impluvium.[14]

The roof around the compluvium was edged with a row of highly ornamented tiles, called antefixes, on which a mask or some other figure was moulded. At the corners there were usually spouts, in the form of lions' or dogs' heads, or any fantastical device which the architect might fancy. The spouts carried the rain-water clear out into the impluvium, rather than letting it run down the walls and pillars, which would damage them. Seeping through the bottom of the impluvium, the water passed into cisterns, from which it was drawn for household purposes.[5]

The compluvial opening might be shaded by a coloured veil,[5] probably of an open, airy weave.

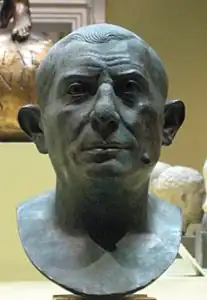

Roof structure

a, a. Side walls.

b. One of the two girders supporting the roof.

c. Crossbeam, resting on the two girders.

d. Short beam of the thickness of c.

e. Corner beam.

f. Rafters, sloping toward the inside.

g. Compluvium, a hole open to the sky.

1. Flat tiles, tegulae.

2. Semicylindrical tiles for covering the joints, imbrices.

3. Gutter tiles.

Five structural types of cavaedia (or atria) are described by the architect Vitruvius:[14]

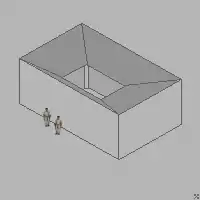

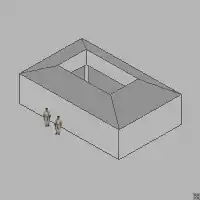

- The atrium tuscanicum has no pillars; beams span the entire room, framing a rectangular hole in the center and supporting the roof (commonest)[14]

- The atrium corinthium has (more than four) pillars along the edges of the roof opening[14] (newly fashionable in Vitruvius' time)

- The atrium tetrastylum has four pillars at the corners of the roof opening[14] (not common[15])

- The atrium displuviatum has outwards-sloping roofs that do not collect water,[14] like most modern roofs (rare[14])

- The atrium testudinatum was fully roofed-over, with another floor on top instead of an opening to the sky (very rare)[14]

The full original description, in his sixth book on engineering, is fairly succinct:

1. There are five different styles of cavaedium, termed according to their construction as follows: Tuscan, Corinthian, tetrastyle, displuviate, and testudinate.

In the Tuscan, the girders that cross the breadth of the atrium have crossbeams on them, and valleys sloping in and running from the angles of the walls to the angles formed by the beams, and the rainwater falls down along the rafters to the roof-opening (compluvium) in the middle.

In the Corinthian, the girders and roof-opening are constructed on these same principles, but the girders run in from the side walls, and are supported all round on columns.

In the tetrastyle, the girders are supported at the angles by columns, an arrangement which relieves and strengthens the girders; for thus they have themselves no great span to support, and they are not loaded down by the crossbeams.

2. In the displuviate, there are beams which slope outwards, supporting the roof and throwing the rainwater off. This style is suitable chiefly in winter residences, for its roof-opening, being high up, is not an obstruction to the light of the dining rooms. It is, however, very troublesome to keep in repair, because the pipes, which are intended to hold the water that comes dripping down the walls all round, cannot take it quickly enough as it runs down from the channels, but get too full and run over, thus spoiling the woodwork and the walls of houses of this style.

The testudinate is employed where the span is not great, and where large rooms are provided in upper stories.

— Vitruvius' De architectura (On Engineering), Wikisource:Ten Books on Architecture/Book VI, Chapter III (translated by Morris Hicky Morgan; public-domain fulltext link)

Tuscan cavaedium

The Tuscan atrium seems to be the most common type in Pompeii.[14] The Tuscan type has the advantage that the walls and pillars are very well-protected from the elements. For a smaller cavaedium, it is a simple, light structure. In a larger cavaedium, though, it requires very massive timber beams.

The Tuscan structure requires two wooden beams that span the entire atrium, running horizontally from wall to wall (see image). Since the atrium is usually longer than it is wide (Vitruvius advises width:length ratios of 3:5, 2:3, or 1:√2), the beams usually run across the width of the atrium. The ends of the beams are typically encastrated (set in a socket in the wall). The beams must be thick enough not to bend excessively under the weight of the roof. As the atrium gets wider, the span gets larger, until it is impractical or unaffordable to get beams which are big enough. The Tuscan style was therefore not used on very large atria. Since a large atrium was a status symbol, the more complex structures used for large atria were sometimes used in small atria which could have been covered with a simpler Tuscan roof.

The main horizontal beams form two sides of the roof opening. The other two sides are formed by shorter horizontal cross-beams, laid across (or jointed into) the main beams. The four valley rafters slope down from the corners of the walls to the corners of the central roof opening. The upper ends of the valley rafters rest on the wall, and the bottom ends on the horizontal beams. The smaller rafters rest their upper ends on the wall, and their lower ends mostly on the beams and cross-beams; the short rafters in the mitered corners of the roof rest on the valley rafters.

Tuscan atrium. Impluvium is mossy; behind, the main door is flanked by two shops. House of Sallust, Pompeii (floorplan).

Tuscan atrium. Impluvium is mossy; behind, the main door is flanked by two shops. House of Sallust, Pompeii (floorplan). Roof framing of the atrium of the small House of the Bronze Herm, Herculaneum (floor plan). The four large diagonal valley rafters and the smaller rafters all slope down from the top of the walls to the horizontal beams.

Roof framing of the atrium of the small House of the Bronze Herm, Herculaneum (floor plan). The four large diagonal valley rafters and the smaller rafters all slope down from the top of the walls to the horizontal beams. Atrium tuscanicum, no pillars. View towards the tablinum. Note the cartibulum (stone table) with unusually simple legs, the impluvium (dry), and the circular (covered) hole giving access to the cistern, just to the right of the impluvium. House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto, Pompeii (another view)

Atrium tuscanicum, no pillars. View towards the tablinum. Note the cartibulum (stone table) with unusually simple legs, the impluvium (dry), and the circular (covered) hole giving access to the cistern, just to the right of the impluvium. House of Marcus Lucretius Fronto, Pompeii (another view)

Tetrastyle cavaedium

In the atrium tetrastylum additional support was required in consequence of the dimensions of the hall; this was given by columns placed at the four angles of the impluvium.[14] This style is not common in Pompeii.[15] These pillars support a beam, which supports a wall, which in turn supports the rafters in the middle of the atrium. There is no need for horizontal beams spanning the entire room; the rafters have shorter spans. This allows a larger room to be roofed.

Atrium tetrastylum, four pillars. Villa San Marco, Stabiae. In this image, the atrium is roofed by a white tarp, laced down at the eaves and supported by scaffolding.

Atrium tetrastylum, four pillars. Villa San Marco, Stabiae. In this image, the atrium is roofed by a white tarp, laced down at the eaves and supported by scaffolding. Same, but with a reconstructed roof. The lack of plaster shows how four horizontal beams, running between the four columns, support a short masonry wall (opus incertum), which in turn supports the rafters

Same, but with a reconstructed roof. The lack of plaster shows how four horizontal beams, running between the four columns, support a short masonry wall (opus incertum), which in turn supports the rafters The figure is leaning against the cartibulum, the lararium is against the wall behind her, and the statue to her right is a small fountain cascading into a shallow trough and thence into the impluvium.

The figure is leaning against the cartibulum, the lararium is against the wall behind her, and the statue to her right is a small fountain cascading into a shallow trough and thence into the impluvium. Atrium tetrastylum (not a very accurate reconstruction)

Atrium tetrastylum (not a very accurate reconstruction)

Corinthian cavaedium

Atrium corinthium, multiple pillars. Small atrium of the House of Menander, Pompeii. Note how the diagonal valley rafters, at the mitered corners, are set lower than the smaller orthogonal rafters. This atrium is smaller than the clear-span Tuscan main atrium in the same house (floorplan model).

Atrium corinthium, multiple pillars. Small atrium of the House of Menander, Pompeii. Note how the diagonal valley rafters, at the mitered corners, are set lower than the smaller orthogonal rafters. This atrium is smaller than the clear-span Tuscan main atrium in the same house (floorplan model). Pompejanum reconstruction (glass roof is an unrealistic modern addition), loosely based on the square atrium in the House of Castor and Pollux, Pompeii (floorplans)

Pompejanum reconstruction (glass roof is an unrealistic modern addition), loosely based on the square atrium in the House of Castor and Pollux, Pompeii (floorplans)_02.jpg.webp) House of the Corinthian Atrium, in Herculaneum. The six pillars are stuccoed tufa, repaired with brick. This atrium is halfway to being a peristyle; planters flank a grassy area. The central marble fountain was fed by an aqueduct, making the original purpose of the atrium, a structure for gathering rainwater, superfluous. The original well remains, beside the nearest pillar (floorplan).

House of the Corinthian Atrium, in Herculaneum. The six pillars are stuccoed tufa, repaired with brick. This atrium is halfway to being a peristyle; planters flank a grassy area. The central marble fountain was fed by an aqueduct, making the original purpose of the atrium, a structure for gathering rainwater, superfluous. The original well remains, beside the nearest pillar (floorplan). 16-column peristyle atrium of the Domvs Romana, in Malta (1st century BC). Note puteal and overflow hole of impluvium.

16-column peristyle atrium of the Domvs Romana, in Malta (1st century BC). Note puteal and overflow hole of impluvium. Atrium with puteal, House of the Lake, Roman-era Delos. Delos was short on freshwater and atria there generally collected it.

Atrium with puteal, House of the Lake, Roman-era Delos. Delos was short on freshwater and atria there generally collected it. Two stories of Corinthian atria/peristyles. House of the Hermes, Roman-era Delos

Two stories of Corinthian atria/peristyles. House of the Hermes, Roman-era Delos

This style has a rectangle of pillars around the roof opening. It is like the tetrastyle, but with more than four pillars. It resembles a peristyle. If the lower layer was sufficiently robust, it could support a second story.

Displuvial cavaedium

In this style, the roofs, instead of sloping down towards the compluvium, sloped outwards from the compluvium, the gutters being on the outer walls; there was still an opening in the roof, and an impluvium to catch the rain falling through (and presumably fed by the gutters). This species of roof, Vitruvius states, is constantly in want of repair, as the water does not easily run away, owing to the stoppage in the rainwater pipes.[14]

This type was rare; only one had been found in Pompeii, as of 1911.[14]

Impluviate atrium

Impluviate atrium Displuviate atrium (rare)

Displuviate atrium (rare) Functioning compluvium roof in the 1865 Lavoir (public laundry-house), Baigneux-les-Juifs, France

Functioning compluvium roof in the 1865 Lavoir (public laundry-house), Baigneux-les-Juifs, France Similar Lavoir from outside.

Similar Lavoir from outside.

Testudinate cavaedium

The atrium testudinatum was employed when the atrium was small and another floor was built over it.[14] The name comes from the Latin word testudo, which means a turtle or tortoise, and by transference a covered vault.

The Encyclopædia Britannica said that no example of this type had been found at Pompeii, as of 1911.[14] While narrow homes had atria that were not flanked by cubiculums and alae, and even atria where the impluvium was set against a wall or in a corner, homes smaller than 5 meters across are generally testudinate.[2]

Proportions

Vitruvius continues by giving the correct proportions for an atrium (length:width ratios for the atrium, and their proportion to that of the opening in the roof, width:height ratios for the atrium, and the proportions (relative to the atrium) of the adjacent rooms that are alcoves open on the atrium side, the tablinum and alae). It is worth noting that many extant atria do not follow his ideal rules.

3. In width and length, atriums are designed according to three classes. The first is laid out by dividing the length into five parts and giving three parts to the width; the second, by dividing it into three parts and assigning two parts to the width; the third, by using the width to describe a square figure with equal sides, drawing a diagonal line in this square, and giving the atrium the length of this diagonal line.

4. Their height up to the girders should be one fourth less than their width, the rest being the proportion assigned to the ceiling and the roof above the girders.

The alae, to the right and left, should have a width equal to one third of the length of the atrium, when that is from thirty to forty feet long. From forty to fifty feet, divide the length by three and one half, and give the alae the result. When it is from fifty to sixty feet in length, devote one fourth of the length to the alae. From sixty to eighty feet, divide the length by four and one half and let the result be the width of the alae. From eighty feet to one hundred feet, the length divided into five parts will produce the right width for the alae. Their lintel beams should be placed high enough to make the height of the alae equal to their width.

5. The tablinum should be given two thirds of the width of the atrium when the latter is twenty feet wide. If it is from thirty to forty feet, let half the width of the atrium be devoted to the tablinum. When it is from forty to sixty feet, divide the width into five parts and let two of these be set apart for the tablinum. In the case of smaller atriums, the symmetrical proportions cannot be the same as in larger. For if, in the case of the smaller, we employ the proportion that belong to the larger, both tablina and alae must be unserviceable, while if, in the case of the larger, we employ the proportions of the smaller, the rooms mentioned will be huge monstrosities. Hence, I have thought it best to describe exactly their respective proportionate sizes, with a view both to convenience and to beauty.

6. The height of the tablinum at the lintel should be one eighth more than its width. Its ceiling should exceed this height by one third of the width. The fauces in the case of smaller atriums should be two thirds, and in the case of larger one half the width of the tablinum. Let the busts of ancestors with their ornaments be set up at a height corresponding to the width of the alae. The proportionate width and height of doors may be settled, if they are Doric, in the Doric manner, and if Ionic, in the Ionic manner, according to the rules of symmetry which have been given about portals in the fourth book. In the roof-opening let an aperture be left with a breadth of not less than one fourth nor more than one third the width of the atrium, and with a length proportionate to that of the atrium.

— Vitruvius' De architectura (On Engineering), Wikisource:Ten Books on Architecture/Book VI, Chapter III (translated by Morris Hicky Morgan; public-domain fulltext link)

He also advises that the size of the atrium of cavaedium be appropriate to the purposes required by the owner's social station: "men of everyday fortune do not need entrance courts, tablina, or atriums built in grand style, because such men are more apt to discharge their social obligations by going round to others than to have others come to them... For capitalists and farmers of the revenue, somewhat comfortable and showy apartments must be constructed, secure against robbery; for advocates and public speakers, handsomer and more roomy, to accommodate meetings; for men of rank who, from holding offices and magistracies, have social obligations to their fellow-citizens, lofty entrance courts in regal style, and most spacious atriums and peristyles, with plantations and walks of some extent in them, appropriate to their dignity."

In many homes in Pompeii, the atrium's walls were placed halfway between the walls behind them and the edge of the impluvium. This meant that the same proportions (almost always 1:√2 width:length) were used for the impluvium edge, the atrium walls, and the next layer of walls (those running outside the tabernae, the cubicles and alae, and the tablinum with its flanking rooms).[2] This arrangement would give the sloping rafters an equal span on each side of the atrium walls.

See also

- Qa'a (room), a space with similar social and physical functions in traditional Middle-eastern architecture

- Machiya and tsubo-niwa, traditional Japanese equivalents of the domus and compluvium

- Burgage plot, narrow town lots in medieval Europe

Notes

- On signage at site, sign photographed at "PompeiiinPictures". pompeii.pictures.

- Weishaar, Joseph (1 May 2013). "Domus, Villa and Insula: A Neo-Rationalist Taxonomy of Housing Types along the Via Consolare-Pompeii". Architecture Undergraduate Honors Theses.

- Laurence, R., and A. Wallace-Hadrill, eds. 1997. "Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond". (JRA Sup-pl. 22. Portsmouth: Journal of Roman Archaeology.), 4, as cited in [2]

- William Smith, D.C.L., LL.D. (1875). "DOMUS: The Roman House (Smith's Dictionary, 1875)". penelope.uchicago.edu. John Murray, London.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Haines, T. L. (Thomas Louis); Yaggy, L. W. (Levi W. ) (1884). Museum of Antiquity: A Description of Ancient Life. Madison, Wisconsin, and Chicago, illinois: J.B. FURMAN & CO. WESTERN PUBLISHING HOUSE.

The atrium, or cavædium, for they appear to have signified the same thing, was the most important, and usually the most splendid apartment of the house. Here the owner received his crowd of morning visitors, who were not admitted to the inner apartments. The term is thus explained by Varro: "The hollow of the house (cavum ædium) is a covered place within the walls, left open to the common use of all. It is called Tuscan, from the Tuscans, after the Romans began to imitate their [29]cavædium. The word atrium is derived from the Atriates, a people of Tuscany, from whom the pattern of it was taken." Originally, then, the atrium was the common room of resort for the whole family, the place of their domestic occupations; and such it probably continued in the humbler ranks of life. A general description of it may easily be given. It was a large apartment, roofed over, but with an opening in the centre, called compluvium, towards which the roof sloped, so as to throw the rain-water into a cistern in the floor called impluvium.

The roof around the compluvium was edged with a row of highly ornamented tiles, called antefixes, on which a mask or some other figure was moulded. At the corners there were usually spouts, in the form of lions' or dogs' heads, or any fantastical device which the architect might fancy, which carried the rain-water clear out into the impluvium, whence it passed into cisterns; from which again it was drawn for household purposes. For drinking, river-water, and still more, well-water, was preferred. Often the atrium was adorned with fountains, supplied through leaden or earthenware pipes, from aqueducts or other raised heads of water; for the Romans knew the property of fluids, which causes them to stand at the same height in communicating vessels. This is distinctly recognized by Pliny,[5] though their common use of aqueducts, in preference to pipes, has led to a supposition that this great hydrostatical principle was unknown to them. The breadth of the impluvium, according to Vitruvius, was not less than a quarter, nor greater than a third, of the whole breadth of the atrium; its length was regulated by the same standard. The opening above it was often shaded by a colored veil, which diffused a softened light, and moderated the intense heat of an Italian sun.[6] The splendid columns of the house of [30]Scaurus, at Rome, were placed, as we learn from Pliny,[7] in the atrium of his house. The walls were painted with landscapes or arabesques—a practice introduced about the time of Augustus—or lined with slabs of foreign and costly marbles, of which the Romans were passionately fond. The pavement was composed of the same precious material, or of still more valuable mosaics. - Servius Danielis, note to Eclogue 4.62 and Aeneid 10.76.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 612.

- Vitruvius' De architectura (On Engineering), Wikisource:Ten Books on Architecture/Book VI, Chapter III (translated by Morris Hicky Morgan; public-domain fulltext link) Quote: The private rooms are those into which nobody has the right to enter without an invitation, such as bedrooms, dining rooms, bathrooms, and all others used for the like purposes. The common are those which any of the people have a perfect right to enter, even without an invitation: that is, entrance courts, cavaedia, peristyles, and all intended for the like purpose.

- Lockey, Ian (2009). "Roman Housing". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- "Roman Domestic architecture: the Domus – Smarthistory". smarthistory.org. Retrieved 16 March 2022.

- Cavazzi, Franco (17 December 2021). "The Roman House". The Roman Empire.

- Vitruvius' De architectura (On Engineering), Wikisource:Ten Books on Architecture/Book VI, Chapter VI (translated by Morris Hicky Morgan); public-domain fulltext link. "The rules on these points will hold not only for houses in town, but also for those in the country, except that in town atriums are usually next to the front door, while in country seats peristyles come first, and then atriums surrounded by paved colonnades opening upon palaestrae and walks. "

- John J. Dobbins and Pedar W. Foss, The World of Pompeii, Routledge Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-415-47577-8

- Chisholm 1911.

- Haines, T. L. (Thomas Louis); Yaggy, L. W. (Levi W. ) (1884). Museum of Antiquity: A Description of Ancient Life. Madison, Wisconsin, and Chicago, illinois: J.B. FURMAN & CO. WESTERN PUBLISHING HOUSE.

It stands next to the House of Sallust, on the south side, being divided from it only by a narrow street. Its front is in the main street or Via Consularis, leading from the gate of Herculaneum to the Forum. Entering by a small vestibule, the visitor finds himself in a tetrastyle atrium (a thing not common at Pompeii), of ample dimensions, considering the character of the house, being about thirty-six feet by thirty. The pillars which supported the ceiling are square and solid, and their size, combined with indications observed in a fragment of the entablature, led Mazois to suppose that, instead of a roof, they had been surmounted by a terrace. The impluvium is marble.

External links

- Video of a digital reconstruction of the House of Lucius Caecilius Iucundus, Pompeii, by the Swedish Pompeii Project (Pompeji Projektet); roof shown at 2:50. Narration in English; interior furnishings and wallpaintings are shown.

References

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Cavaedium". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 560.

_WML_008.JPG.webp)