Cavitation

Cavitation is a phenomenon in which the static pressure of a liquid reduces to below the liquid's vapour pressure, leading to the formation of small vapor-filled cavities in the liquid. When subjected to higher pressure, these cavities, called "bubbles" or "voids", collapse and can generate shock waves that may damage machinery. These shock waves are strong when they are very close to the imploded bubble, but rapidly weaken as they propagate away from the implosion. Cavitation is a significant cause of wear in some engineering contexts. Collapsing voids that implode near to a metal surface cause cyclic stress through repeated implosion. This results in surface fatigue of the metal, causing a type of wear also called "cavitation". The most common examples of this kind of wear are to pump impellers, and bends where a sudden change in the direction of liquid occurs. Cavitation is usually divided into two classes of behavior: inertial (or transient) cavitation and non-inertial cavitation.

The process in which a void or bubble in a liquid rapidly collapses, producing a shock wave, is called inertial cavitation. Inertial cavitation occurs in nature in the strikes of mantis shrimp and pistol shrimp, as well as in the vascular tissues of plants. In manufactured objects, it can occur in control valves, pumps, propellers and impellers.

Non-inertial cavitation is the process in which a bubble in a fluid is forced to oscillate in size or shape due to some form of energy input, such as an acoustic field. Such cavitation is often employed in ultrasonic cleaning baths and can also be observed in pumps, propellers, etc.

Since the shock waves formed by collapse of the voids are strong enough to cause significant damage to parts, cavitation is typically an undesirable phenomenon in machinery (although desirable if intentionally used, for example, to sterilize contaminated surgical instruments, break down pollutants in water purification systems, emulsify tissue for cataract surgery or kidney stone lithotripsy, or homogenize fluids). It is very often specifically prevented in the design of machines such as turbines or propellers, and eliminating cavitation is a major field in the study of fluid dynamics. However, it is sometimes useful and does not cause damage when the bubbles collapse away from machinery, such as in supercavitation.

Physics

Inertial cavitation

Inertial cavitation was first observed in the late 19th century, considering the collapse of a spherical void within a liquid. When a volume of liquid is subjected to a sufficiently low pressure, it may rupture and form a cavity. This phenomenon is coined cavitation inception and may occur behind the blade of a rapidly rotating propeller or on any surface vibrating in the liquid with sufficient amplitude and acceleration. A fast-flowing river can cause cavitation on rock surfaces, particularly when there is a drop-off, such as on a waterfall.

Other ways of generating cavitation voids involve the local deposition of energy, such as an intense focused laser pulse (optic cavitation) or with an electrical discharge through a spark. Vapor gases evaporate into the cavity from the surrounding medium; thus, the cavity is not a vacuum at all, but rather a low-pressure vapor (gas) bubble. Once the conditions which caused the bubble to form are no longer present, such as when the bubble moves downstream, the surrounding liquid begins to implode due its higher pressure, building up inertia as it moves inward. As the bubble finally collapses, the inward inertia of the surrounding liquid causes a sharp increase of pressure and temperature of the vapor within. The bubble eventually collapses to a minute fraction of its original size, at which point the gas within dissipates into the surrounding liquid via a rather violent mechanism which releases a significant amount of energy in the form of an acoustic shock wave and as visible light. At the point of total collapse, the temperature of the vapor within the bubble may be several thousand kelvin, and the pressure several hundred atmospheres.[1]

Inertial cavitation can also occur in the presence of an acoustic field. Microscopic gas bubbles that are generally present in a liquid will be forced to oscillate due to an applied acoustic field. If the acoustic intensity is sufficiently high, the bubbles will first grow in size and then rapidly collapse. Hence, inertial cavitation can occur even if the rarefaction in the liquid is insufficient for a Rayleigh-like void to occur. High-power ultrasonics usually utilize the inertial cavitation of microscopic vacuum bubbles for treatment of surfaces, liquids, and slurries.

The physical process of cavitation inception is similar to boiling. The major difference between the two is the thermodynamic paths that precede the formation of the vapor. Boiling occurs when the local temperature of the liquid reaches the saturation temperature, and further heat is supplied to allow the liquid to sufficiently phase change into a gas. Cavitation inception occurs when the local pressure falls sufficiently far below the saturated vapor pressure, a value given by the tensile strength of the liquid at a certain temperature.[2]

In order for cavitation inception to occur, the cavitation "bubbles" generally need a surface on which they can nucleate. This surface can be provided by the sides of a container, by impurities in the liquid, or by small undissolved microbubbles within the liquid. It is generally accepted that hydrophobic surfaces stabilize small bubbles. These pre-existing bubbles start to grow unbounded when they are exposed to a pressure below the threshold pressure, termed Blake's threshold.[3] The presence of an incompressible core inside a cavitation nucleus substantially lowers the cavitation threshold below the Blake threshold.[4]

The vapor pressure here differs from the meteorological definition of vapor pressure, which describes the partial pressure of water in the atmosphere at some value less than 100% saturation. Vapor pressure as relating to cavitation refers to the vapor pressure in equilibrium conditions and can therefore be more accurately defined as the equilibrium (or saturated) vapor pressure.

Non-inertial cavitation is the process in which small bubbles in a liquid are forced to oscillate in the presence of an acoustic field, when the intensity of the acoustic field is insufficient to cause total bubble collapse. This form of cavitation causes significantly less erosion than inertial cavitation, and is often used for the cleaning of delicate materials, such as silicon wafers.

Hydrodynamic cavitation

Hydrodynamic cavitation is the process of vaporisation, bubble generation and bubble implosion which occurs in a flowing liquid as a result of a decrease and subsequent increase in local pressure. Cavitation will only occur if the local pressure declines to some point below the saturated vapor pressure of the liquid and subsequent recovery above the vapor pressure. If the recovery pressure is not above the vapor pressure then flashing is said to have occurred. In pipe systems, cavitation typically occurs either as the result of an increase in the kinetic energy (through an area constriction) or an increase in the pipe elevation.

Hydrodynamic cavitation can be produced by passing a liquid through a constricted channel at a specific flow velocity or by mechanical rotation of an object through a liquid. In the case of the constricted channel and based on the specific (or unique) geometry of the system, the combination of pressure and kinetic energy can create the hydrodynamic cavitation cavern downstream of the local constriction generating high energy cavitation bubbles.

Based on the thermodynamic phase change diagram, an increase in temperature could initiate a known phase change mechanism known as boiling. However, a decrease in static pressure could also help one pass the multi-phase diagram and initiate another phase change mechanism known as cavitation. On the other hand, a local increase in flow velocity could lead to a static pressure drop to the critical point at which cavitation could be initiated (based on Bernoulli's principle). The critical pressure point is vapor saturated pressure. In a closed fluidic system where no flow leakage is detected, a decrease in cross-sectional area would lead to velocity increment and hence static pressure drop. This is the working principle of many hydrodynamic cavitation based reactors for different applications such as water treatment, energy harvesting, heat transfer enhancement, food processing, etc.[5]

There are different flow patterns detected as a cavitation flow progresses: inception, developed flow, supercavitation, and choked flow. Inception is the first moment that the second phase (gas phase) appears in the system. This is the weakest cavitating flow captured in a system corresponding to the highest cavitation number. When the cavities grow and becomes larger in size in the orifice or venturi structures, developed flow is recorded. The most intense cavitating flow is known as supercavitation where theoretically all the nozzle area of an orifice is filled with gas bubbles. This flow regime corresponds to the lowest cavitation number in a system. After supercavitation, the system is not capable of passing more flow. Hence, velocity does not change while the upstream pressure increase. This would lead to an increase in cavitation number which shows that choked flow occurred.[6]

The process of bubble generation, and the subsequent growth and collapse of the cavitation bubbles, results in very high energy densities and in very high local temperatures and local pressures at the surface of the bubbles for a very short time. The overall liquid medium environment, therefore, remains at ambient conditions. When uncontrolled, cavitation is damaging; by controlling the flow of the cavitation, however, the power can be harnessed and non-destructive. Controlled cavitation can be used to enhance chemical reactions or propagate certain unexpected reactions because free radicals are generated in the process due to disassociation of vapors trapped in the cavitating bubbles.[7]

Orifices and venturi are reported to be widely used for generating cavitation. A venturi has an inherent advantage over an orifice because of its smooth converging and diverging sections, such that it can generate a higher flow velocity at the throat for a given pressure drop across it. On the other hand, an orifice has an advantage that it can accommodate a greater number of holes (larger perimeter of holes) in a given cross sectional area of the pipe.[8]

The cavitation phenomenon can be controlled to enhance the performance of high-speed marine vessels and projectiles, as well as in material processing technologies, in medicine, etc. Controlling the cavitating flows in liquids can be achieved only by advancing the mathematical foundation of the cavitation processes. These processes are manifested in different ways, the most common ones and promising for control being bubble cavitation and supercavitation. The first exact classical solution should perhaps be credited to the well-known solution by Hermann von Helmholtz in 1868.[9] The earliest distinguished studies of academic type on the theory of a cavitating flow with free boundaries and supercavitation were published in the book Jets, wakes and cavities[10] followed by Theory of jets of ideal fluid.[11] Widely used in these books was the well-developed theory of conformal mappings of functions of a complex variable, allowing one to derive a large number of exact solutions of plane problems. Another venue combining the existing exact solutions with approximated and heuristic models was explored in the work Hydrodynamics of Flows with Free Boundaries[12] that refined the applied calculation techniques based on the principle of cavity expansion independence, theory of pulsations and stability of elongated axisymmetric cavities, etc.[13] and in Dimensionality and similarity methods in the problems of the hydromechanics of vessels.[14]

A natural continuation of these studies was recently presented in The Hydrodynamics of Cavitating Flows[15] – an encyclopedic work encompassing all the best advances in this domain for the last three decades, and blending the classical methods of mathematical research with the modern capabilities of computer technologies. These include elaboration of nonlinear numerical methods of solving 3D cavitation problems, refinement of the known plane linear theories, development of asymptotic theories of axisymmetric and nearly axisymmetric flows, etc. As compared to the classical approaches, the new trend is characterized by expansion of the theory into the 3D flows. It also reflects a certain correlation with current works of an applied character on the hydrodynamics of supercavitating bodies.

Hydrodynamic cavitation can also improve some industrial processes. For instance, cavitated corn slurry shows higher yields in ethanol production compared to uncavitated corn slurry in dry milling facilities.[16]

This is also used in the mineralization of bio-refractory compounds which otherwise would need extremely high temperature and pressure conditions since free radicals are generated in the process due to the dissociation of vapors trapped in the cavitating bubbles, which results in either the intensification of the chemical reaction or may even result in the propagation of certain reactions not possible under otherwise ambient conditions.[17]

Applications

Chemical engineering

In industry, cavitation is often used to homogenize, or mix and break down, suspended particles in a colloidal liquid compound such as paint mixtures or milk. Many industrial mixing machines are based upon this design principle. It is usually achieved through impeller design or by forcing the mixture through an annular opening that has a narrow entrance orifice with a much larger exit orifice. In the latter case, the drastic decrease in pressure as the liquid accelerates into a larger volume induces cavitation. This method can be controlled with hydraulic devices that control inlet orifice size, allowing for dynamic adjustment during the process, or modification for different substances. The surface of this type of mixing valve, against which surface the cavitation bubbles are driven causing their implosion, undergoes tremendous mechanical and thermal localized stress; they are therefore often constructed of extremely strong and hard materials such as stainless steel, Stellite, or even polycrystalline diamond (PCD).

Cavitating water purification devices have also been designed, in which the extreme conditions of cavitation can break down pollutants and organic molecules. Spectral analysis of light emitted in sonochemical reactions reveal chemical and plasma-based mechanisms of energy transfer. The light emitted from cavitation bubbles is termed sonoluminescence.

Use of this technology has been tried successfully in alkali refining of vegetable oils.[18]

Hydrophobic chemicals are attracted underwater by cavitation as the pressure difference between the bubbles and the liquid water forces them to join. This effect may assist in protein folding.[19]

Biomedical

Cavitation plays an important role for the destruction of kidney stones in shock wave lithotripsy.[20] Currently, tests are being conducted as to whether cavitation can be used to transfer large molecules into biological cells (sonoporation). Nitrogen cavitation is a method used in research to lyse cell membranes while leaving organelles intact.

Cavitation plays a key role in non-thermal, non-invasive fractionation of tissue for treatment of a variety of diseases[21] and can be used to open the blood-brain barrier to increase uptake of neurological drugs in the brain.[22]

Cavitation also plays a role in HIFU, a thermal non-invasive treatment methodology for cancer.[23]

In wounds caused by high velocity impacts (like for example bullet wounds) there are also effects due to cavitation. The exact wounding mechanisms are not completely understood yet as there is temporary cavitation, and permanent cavitation together with crushing, tearing and stretching. Also the high variance in density within the body makes it hard to determine its effects.[24]

Ultrasound sometimes is used to increase bone formation, for instance in post-surgical applications.[25]

It has been suggested that the sound of "cracking" knuckles derives from the collapse of cavitation in the synovial fluid within the joint.[26]

Cavitation can also form Ozone micro-nanobubbles which shows promise in dental applications.[27]

Cleaning

In industrial cleaning applications, cavitation has sufficient power to overcome the particle-to-substrate adhesion forces, loosening contaminants. The threshold pressure required to initiate cavitation is a strong function of the pulse width and the power input. This method works by generating acoustic cavitation in the cleaning fluid, picking up and carrying contaminant particles away in the hope that they do not reattach to the material being cleaned (which is a possibility when the object is immersed, for example in an ultrasonic cleaning bath). The same physical forces that remove contaminants also have the potential to damage the target being cleaned.

Eggs

Cavitation has been applied to egg pasteurization. A hole-filled rotor produces cavitation bubbles, heating the liquid from within. Equipment surfaces stay cooler than the passing liquid, so eggs do not harden as they did on the hot surfaces of older equipment. The intensity of cavitation can be adjusted, making it possible to tune the process for minimum protein damage.[28]

Vegetable oil production

Cavitation has been applied to vegetable oil degumming and refining since 2011 and is considered a proven and standard technology in this application. The implementation of hydrodynamic cavitation in the degumming and refining process allows for a significant reduction in process aid, such as chemicals, water and bleaching clay, use.[29][30][31][32][33]

Biodiesel

Cavitation has been applied to Biodiesel production since 2011 and is considered a proven and standard technology in this application. The implementation of hydrodynamic cavitation in the transesterification process allows for a significant reduction in catalyst use, quality improvement and production capacity increase.[34][35][36]

Cavitation damage

Cavitation is usually an undesirable occurrence. In devices such as propellers and pumps, cavitation causes a great deal of noise, damage to components, vibrations, and a loss of efficiency. Noise caused by cavitation can be particularly undesirable in naval vessels where such noise may render them more easily detectable by passive sonar. Cavitation has also become a concern in the renewable energy sector as it may occur on the blade surface of tidal stream turbines.[37]

When the cavitation bubbles collapse, they force energetic liquid into very small volumes, thereby creating spots of high temperature and emitting shock waves, the latter of which are a source of noise. The noise created by cavitation is a particular problem for military submarines, as it increases the chances of being detected by passive sonar.

Although the collapse of a small cavity is a relatively low-energy event, highly localized collapses can erode metals, such as steel, over time.[38] The pitting caused by the collapse of cavities produces great wear on components and can dramatically shorten a propeller's or pump's lifetime.

After a surface is initially affected by cavitation, it tends to erode at an accelerating pace. The cavitation pits increase the turbulence of the fluid flow and create crevices that act as nucleation sites for additional cavitation bubbles. The pits also increase the components' surface area and leave behind residual stresses. This makes the surface more prone to stress corrosion.[39]

Pumps and propellers

Major places where cavitation occurs are in pumps, on propellers, or at restrictions in a flowing liquid.

As an impeller's (in a pump) or propeller's (as in the case of a ship or submarine) blades move through a fluid, low-pressure areas are formed as the fluid accelerates around and moves past the blades. The faster the blade moves, the lower the pressure can become around it. As it reaches vapor pressure, the fluid vaporizes and forms small bubbles of gas. This is cavitation. When the bubbles collapse later, they typically cause very strong local shock waves in the fluid, which may be audible and may even damage the blades.

Cavitation in pumps may occur in two different forms:

Suction cavitation

Suction cavitation occurs when the pump suction is under a low-pressure/high-vacuum condition where the liquid turns into a vapor at the eye of the pump impeller. This vapor is carried over to the discharge side of the pump, where it no longer sees vacuum and is compressed back into a liquid by the discharge pressure. This imploding action occurs violently and attacks the face of the impeller. An impeller that has been operating under a suction cavitation condition can have large chunks of material removed from its face or very small bits of material removed, causing the impeller to look spongelike. Both cases will cause premature failure of the pump, often due to bearing failure. Suction cavitation is often identified by a sound like gravel or marbles in the pump casing.

Common causes of suction cavitation can include clogged filters, pipe blockage on the suction side, poor piping design, pump running too far right on the pump curve, or conditions not meeting NPSH (net positive suction head) requirements.[40]

In automotive applications, a clogged filter in a hydraulic system (power steering, power brakes) can cause suction cavitation making a noise that rises and falls in synch with engine RPM. It is fairly often a high pitched whine, like set of nylon gears not quite meshing correctly.

Discharge cavitation

Discharge cavitation occurs when the pump discharge pressure is extremely high, normally occurring in a pump that is running at less than 10% of its best efficiency point. The high discharge pressure causes the majority of the fluid to circulate inside the pump instead of being allowed to flow out the discharge. As the liquid flows around the impeller, it must pass through the small clearance between the impeller and the pump housing at extremely high flow velocity. This flow velocity causes a vacuum to develop at the housing wall (similar to what occurs in a venturi), which turns the liquid into a vapor. A pump that has been operating under these conditions shows premature wear of the impeller vane tips and the pump housing. In addition, due to the high pressure conditions, premature failure of the pump's mechanical seal and bearings can be expected. Under extreme conditions, this can break the impeller shaft.

Discharge cavitation in joint fluid is thought to cause the popping sound produced by bone joint cracking, for example by deliberately cracking one's knuckles.

Cavitation solutions

Since all pumps require well-developed inlet flow to meet their potential, a pump may not perform or be as reliable as expected due to a faulty suction piping layout such as a close-coupled elbow on the inlet flange. When poorly developed flow enters the pump impeller, it strikes the vanes and is unable to follow the impeller passage. The liquid then separates from the vanes causing mechanical problems due to cavitation, vibration and performance problems due to turbulence and poor filling of the impeller. This results in premature seal, bearing and impeller failure, high maintenance costs, high power consumption, and less-than-specified head and/or flow.

To have a well-developed flow pattern, pump manufacturer's manuals recommend about (10 diameters?) of straight pipe run upstream of the pump inlet flange. Unfortunately, piping designers and plant personnel must contend with space and equipment layout constraints and usually cannot comply with this recommendation. Instead, it is common to use an elbow close-coupled to the pump suction which creates a poorly developed flow pattern at the pump suction.[41]

With a double-suction pump tied to a close-coupled elbow, flow distribution to the impeller is poor and causes reliability and performance shortfalls. The elbow divides the flow unevenly with more channeled to the outside of the elbow. Consequently, one side of the double-suction impeller receives more flow at a higher flow velocity and pressure while the starved side receives a highly turbulent and potentially damaging flow. This degrades overall pump performance (delivered head, flow and power consumption) and causes axial imbalance which shortens seal, bearing and impeller life.[42] To overcome cavitation: Increase suction pressure if possible. Decrease liquid temperature if possible. Throttle back on the discharge valve to decrease flow-rate. Vent gases off the pump casing.

Control valves

Cavitation can occur in control valves.[43] If the actual pressure drop across the valve as defined by the upstream and downstream pressures in the system is greater than the sizing calculations allow, pressure drop flashing or cavitation may occur. The change from a liquid state to a vapor state results from the increase in flow velocity at or just downstream of the greatest flow restriction which is normally the valve port. To maintain a steady flow of liquid through a valve the flow velocity must be greatest at the vena contracta or the point where the cross sectional area is the smallest. This increase in flow velocity is accompanied by a substantial decrease in the fluid pressure which is partially recovered downstream as the area increases and flow velocity decreases. This pressure recovery is never completely to the level of the upstream pressure. If the pressure at the vena contracta drops below the vapor pressure of the fluid bubbles will form in the flow stream. If the pressure recovers after the valve to a pressure that is once again above the vapor pressure, then the vapor bubbles will collapse and cavitation will occur.

Spillways

When water flows over a dam spillway, the irregularities on the spillway surface will cause small areas of flow separation in a high-speed flow, and, in these regions, the pressure will be lowered. If the flow velocities are high enough the pressure may fall to below the local vapor pressure of the water and vapor bubbles will form. When these are carried downstream into a high pressure region the bubbles collapse giving rise to high pressures and possible cavitation damage.

Experimental investigations show that the damage on concrete chute and tunnel spillways can start at clear water flow velocities of between 12 and 15 m/s (27 and 34 mph), and, up to flow velocities of 20 m/s (45 mph), it may be possible to protect the surface by streamlining the boundaries, improving the surface finishes or using resistant materials.[44]

When some air is present in the water the resulting mixture is compressible and this damps the high pressure caused by the bubble collapses.[45] If the flow velocities near the spillway invert are sufficiently high, aerators (or aeration devices) must be introduced to prevent cavitation. Although these have been installed for some years, the mechanisms of air entrainment at the aerators and the slow movement of the air away from the spillway surface are still challenging.[46][47][48][49]

The spillway aeration device design is based upon a small deflection of the spillway bed (or sidewall) such as a ramp and offset to deflect the high flow velocity flow away from the spillway surface. In the cavity formed below the nappe, a local subpressure beneath the nappe is produced by which air is sucked into the flow. The complete design includes the deflection device (ramp, offset) and the air supply system.

Engines

Some larger diesel engines suffer from cavitation due to high compression and undersized cylinder walls. Vibrations of the cylinder wall induce alternating low and high pressure in the coolant against the cylinder wall. The result is pitting of the cylinder wall, which will eventually let cooling fluid leak into the cylinder and combustion gases to leak into the coolant.

It is possible to prevent this from happening with the use of chemical additives in the cooling fluid that form a protective layer on the cylinder wall. This layer will be exposed to the same cavitation, but rebuilds itself. Additionally a regulated overpressure in the cooling system (regulated and maintained by the coolant filler cap spring pressure) prevents the forming of cavitation.

From about the 1980s, new designs of smaller gasoline engines also displayed cavitation phenomena. One answer to the need for smaller and lighter engines was a smaller coolant volume and a correspondingly higher coolant flow velocity. This gave rise to rapid changes in flow velocity and therefore rapid changes of static pressure in areas of high heat transfer. Where resulting vapor bubbles collapsed against a surface, they had the effect of first disrupting protective oxide layers (of cast aluminium materials) and then repeatedly damaging the newly formed surface, preventing the action of some types of corrosion inhibitor (such as silicate based inhibitors). A final problem was the effect that increased material temperature had on the relative electrochemical reactivity of the base metal and its alloying constituents. The result was deep pits that could form and penetrate the engine head in a matter of hours when the engine was running at high load and high speed. These effects could largely be avoided by the use of organic corrosion inhibitors or (preferably) by designing the engine head in such a way as to avoid certain cavitation inducing conditions.

In nature

Geology

Some hypotheses relating to diamond formation posit a possible role for cavitation—namely cavitation in the kimberlite pipes providing the extreme pressure needed to change pure carbon into the rare allotrope that is diamond. The loudest three sounds ever recorded, during the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, are now understood as the bursts of three huge cavitation bubbles, each larger than the last, formed in the volcano's throat. Rising magma, filled with dissolved gasses and under immense pressure, encountered a different magma that compressed easily, allowing bubbles to grow and combine.[50][51]

Vascular plants

Cavitation can occur in the xylem of vascular plants.[52][53] The sap vaporizes locally so that either the vessel elements or tracheids are filled with water vapor. Plants are able to repair cavitated xylem in a number of ways. For plants less than 50 cm tall, root pressure can be sufficient to redissolve the vapor. Larger plants direct solutes into the xylem via ray cells, or in tracheids, via osmosis through bordered pits. Solutes attract water, the pressure rises and vapor can redissolve. In some trees, the sound of the cavitation is audible, particularly in summer, when the rate of evapotranspiration is highest. Some deciduous trees have to shed leaves in the autumn partly because cavitation increases as temperatures decrease.[53]

Spore dispersal in plants

Cavitation plays a role in the spore dispersal mechanisms of certain plants. In ferns, for example, the fern sporangium acts as a catapult that launches spores into the air. The charging phase of the catapult is driven by water evaporation from the annulus cells, which triggers a pressure decrease. When the compressive pressure reaches approximately 9 MPa, cavitation occurs. This rapid event triggers spore dispersal due to the elastic energy released by the annulus structure. The initial spore acceleration is extremely large – up to 105 times the gravitational acceleration.[54]

Marine life

Just as cavitation bubbles form on a fast-spinning boat propeller, they may also form on the tails and fins of aquatic animals. This primarily occurs near the surface of the ocean, where the ambient water pressure is low.

Cavitation may limit the maximum swimming speed of powerful swimming animals like dolphins and tuna.[55] Dolphins may have to restrict their speed because collapsing cavitation bubbles on their tail are painful. Tuna have bony fins without nerve endings and do not feel pain from cavitation. They are slowed down when cavitation bubbles create a vapor film around their fins. Lesions have been found on tuna that are consistent with cavitation damage.[56]

Some sea animals have found ways to use cavitation to their advantage when hunting prey. The pistol shrimp snaps a specialized claw to create cavitation, which can kill small fish. The mantis shrimp (of the smasher variety) uses cavitation as well in order to stun, smash open, or kill the shellfish that it feasts upon.[57]

Thresher sharks use 'tail slaps' to debilitate their small fish prey and cavitation bubbles have been seen rising from the apex of the tail arc.[58][59]

Coastal erosion

In the last half-decade, coastal erosion in the form of inertial cavitation has been generally accepted.[60] Bubbles in an incoming wave are forced into cracks in the cliff being eroded. Varying pressure decompresses some vapor pockets which subsequently implode. The resulting pressure peaks can blast apart fractions of the rock.

History

As early as 1754, the Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler (1707–1783) speculated about the possibility of cavitation.[61] In 1859, the English mathematician William Henry Besant (1828–1917) published a solution to the problem of the dynamics of the collapse of a spherical cavity in a fluid, which had been presented by the Anglo-Irish mathematician George Stokes (1819–1903) as one of the Cambridge [University] Senate-house problems and riders for the year 1847.[62][63][64] In 1894, Irish fluid dynamicist Osborne Reynolds (1842–1912) studied the formation and collapse of vapor bubbles in boiling liquids and in constricted tubes.[65]

The term cavitation first appeared in 1895 in a paper by John Isaac Thornycroft (1843–1928) and Sydney Walker Barnaby (1855–1925)—son of Sir Nathaniel Barnaby (1829 – 1915), who had been Chief Constructor of the Royal Navy—to whom it had been suggested by the British engineer Robert Edmund Froude (1846–1924), third son of the English hydrodynamicist William Froude (1810–1879).[66][67] Early experimental studies of cavitation were conducted in 1894-5 by Thornycroft and Barnaby and by the Anglo-Irish engineer Charles Algernon Parsons (1854-1931), who constructed a stroboscopic apparatus to study the phenomenon.[68][69][70] Thornycroft and Barnaby were the first researchers to observe cavitation on the back sides of propeller blades.[71]

In 1917, the British physicist Lord Rayleigh (1842–1919) extended Besant's work, publishing a mathematical model of cavitation in an incompressible fluid (ignoring surface tension and viscosity), in which he also determined the pressure in the fluid.[72] The mathematical models of cavitation which were developed by British engineer Stanley Smith Cook (1875–1952) and by Lord Rayleigh revealed that collapsing bubbles of vapor could generate very high pressures, which were capable of causing the damage that had been observed on ships' propellers.[73][74] Experimental evidence of cavitation causing such high pressures was initially collected in 1952 by Mark Harrison (a fluid dynamicist and acoustician at the U.S. Navy's David Taylor Model Basin at Carderock, Maryland, USA) who used acoustic methods and in 1956 by Wernfried Güth (a physicist and acoustician of Göttigen University, Germany) who used optical Schlieren photography.[75][76][77]

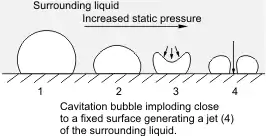

In 1944, Soviet scientists Mark Iosifovich Kornfeld (1908–1993) and L. Suvorov of the Leningrad Physico-Technical Institute (now: the Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Russia) proposed that during cavitation, bubbles in the vicinity of a solid surface do not collapse symmetrically; instead, a dimple forms on the bubble at a point opposite the solid surface and this dimple evolves into a jet of liquid. This jet of liquid damages the solid surface.[78] This hypothesis was supported in 1951 by theoretical studies by Maurice Rattray, Jr., a doctoral student at the California Institute of Technology.[79] Kornfeld and Suvorov's hypothesis was confirmed experimentally in 1961 by Charles F. Naudé and Albert T. Ellis, fluid dynamicists at the California Institute of Technology.[80]

A series of experimental investigations of the propagation of strong shock wave (SW) in a liquid with gas bubbles, which made it possible to establish the basic laws governing the process, the mechanism for the transformation of the energy of the SW, attenuation of the SW, and the formation of the structure, and experiments on the analysis of the attenuation of waves in bubble screens with different acoustic properties were begun by pioneer works of Soviet scientist prof.V.F. Minin at the Institute of Hydrodynamics (Novosibirsk, Russia) in 1957–1960, who examined also the first convenient model of a screen - a sequence of alternating flat one-dimensional liquid and gas layers.[81] In an experimental investigations of the dynamics of the form of pulsating gaseous cavities and interaction of SW with bubble clouds in 1957–1960 V.F. Minin discovered that under the action of SW a bubble collapses asymmetrically with the formation of a cumulative jet, which forms in the process of collapse and causes fragmentation of the bubble.[81]

See also

- Cavitation number

- Cavitation modelling – type of computational fluid dynamic

- Erosion corrosion of copper water tubes

- Rayleigh-Plesset equation – Ordinary differential equation

- Sonoluminescence – Light emissions from collapsing, sound-induced bubbles

- Supercavitation – Use of a cavitation bubble to reduce skin friction drag on a submerged object

- Supercavitating propeller – Marine propeller designed to operate with a full cavitation bubble

- Water hammer – Pressure surge when a fluid is forced to stop or change direction suddenly

- Water tunnel (hydrodynamic) – hydrodynamic test facility

- Ultrasonic cavitation device – Surgical device using ultrasound to break up tissues

References

- Riesz, P.; Berdahl, D.; Christman, C.L. (1985). "Free radical generation by ultrasound in aqueous and nonaqueous solutions". Environmental Health Perspectives. 64: 233–252. doi:10.2307/3430013. JSTOR 3430013. PMC 1568618. PMID 3007091.

- Brennen, Christopher. "Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics" (PDF). Oxford University Press. p. 21. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2012-10-04. Retrieved 2015-02-27.

- Postema M, de Jong N, Schmitz G (September 2005). "Shell rupture threshold, fragmentation threshold, blake threshold". IEEE Ultrasonics Symposium, 2005. Vol. 3. Rotterdam, Netherlands. pp. 1708–1711. doi:10.1109/ULTSYM.2005.1603194. ISBN 0-7803-9382-1. S2CID 5683516.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Carlson CS, Matsumoto R, Fushino K, Shinzato M, Kudo N, Postema M (2021). "Nucleation threshold of carbon black ultrasound contrast agent". Japanese Journal of Applied Physics. 60 (SD): SDDA06. Bibcode:2021JaJAP..60DDA06C. doi:10.35848/1347-4065/abef0f. S2CID 233539493.

- Gevari, Moein Talebian; Abbasiasl, Taher; Niazi, Soroush; Ghorbani, Morteza; Koşar, Ali (May 5, 2020). "Direct and indirect thermal applications of hydrodynamic and acoustic cavitation: A review". Applied Thermal Engineering. 171: 115065. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2020.115065. ISSN 1359-4311. S2CID 214446752.

- Gevari, Moein Talebian; Shafaghi, Ali Hosseinpour; Villanueva, Luis Guillermo; Ghorbani, Morteza; Koşar, Ali (January 2020). "Engineered Lateral Roughness Element Implementation and Working Fluid Alteration to Intensify Hydrodynamic Cavitating Flows on a Chip for Energy Harvesting". Micromachines. 11 (1): 49. doi:10.3390/mi11010049. PMC 7019874. PMID 31906037.

- STOPAR, DAVID. "HYDRODYNAMIC CAVITATION". Retrieved 2020-01-17.

- Moholkar, Vijayanand S.; Pandit, Aniruddha B. (1997). "Bubble Behavior in Hydrodynamic Cavitation: Effect of Turbulence". AIChE Journal. 43 (6): 1641–1648. doi:10.1002/aic.690430628.

- Helmholtz, Hermann von (1868). "Über diskontinuierliche Flüssigkeits-Bewegungen" [On discontinuous motions of fluids]. Monatsberichte der Königlichen Preussische Akademie des Wissenschaften zu Berlin (Monthly Reports of the Royal Prussian Academy of Sciences at Berlin) (in German). 23: 215–228.

- Birkhoff, G, Zarantonello. E (1957) Jets, wakes and cavities. New York: Academic Press. 406p.

- Gurevich, MI (1978) Theory of jets of ideal fluid. Nauka, Moscow, 536p. (in Russian)

- Logvinovich, GV (1969) Hydrodynamics of Flows with Free Boundaries. Naukova dumka, Kiev, 215p. (In Russian)

- Knapp, RT, Daili, JW, Hammit, FG (1970) Cavitation. New York: Mc Graw Hill Book Company. 578p.

- Epshtein, LA (1970) Dimensionality and similarity methods in the problems of the hydromechanics of vessels. Sudostroyenie, Leningrad, 208p. (In Russian)

- Terentiev, A, Kirschner, I, Uhlman, J, (2011) The Hydrodynamics of Cavitating Flows. Backbone Publishing Company, 598pp.

- Oleg Kozyuk; Arisdyne Systems Inc.; US patent US 7,667,082 B2; Apparatus and Method for Increasing Alcohol Yield from Grain

- Gogate, P. R.; Kabadi, A. M. (2009). "A review of applications of cavitation in biochemical engineering/biotechnology". Biochemical Engineering Journal. 44 (1): 60–72. doi:10.1016/j.bej.2008.10.006.

- "Edible Oil Refining". Cavitation Technologies, Inc. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- "Sandia researchers solve mystery of attractive surfaces". Sandia National Laboratories. August 2, 2006. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- Pishchalnikov, Y. A; Sapozhnikov, O. A; Bailey, M. R; Williams Jr, J. C; Cleveland, R. O; Colonius, T; Crum, L. A; Evan, A. P; McAteer, J. A (2003). "Cavitation Bubble Cluster Activity in the Breakage of Kidney Stones by Lithotripter Shock Waves". Journal of Endourology. 17 (7): 435–446. doi:10.1089/089277903769013568. PMC 2442573. PMID 14565872.

- "University of Michigan. Therapeutic Ultrasound Group, Biomedical Engineering Department, University of Michigan".

- Chu, Po-Chun; Chai, Wen-Yen; Tsai, Chih-Hung; Kang, Shih-Tsung; Yeh, Chih-Kuang; Liu, Hao-Li (2016). "Focused Ultrasound-Induced Blood-Brain Barrier Opening: Association with Mechanical Index and Cavitation Index Analyzed by Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced Magnetic-Resonance Imaging". Scientific Reports. 6: 33264. Bibcode:2016NatSR...633264C. doi:10.1038/srep33264. PMC 5024096. PMID 27630037.

- Rabkin, Brian A.; Zderic, Vesna; Vaezy, Shahram (July 1, 2005). "Hyperecho in ultrasound images of HIFU therapy: Involvement of cavitation". Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology. 31 (7): 947–956. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.03.015. ISSN 0301-5629. PMID 15972200.

- Stefanopoulos, Panagiotis K.; Mikros, George; Pinialidis, Dionisios E.; Oikonomakis, Ioannis N.; Tsiatis, Nikolaos E.; Janzon, Bo (September 1, 2009). "Wound ballistics of military rifle bullets: An update on controversial issues and associated misconceptions". The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery. 87 (3): 690–698. doi:10.1097/TA.0000000000002290. PMID 30939579. S2CID 92996795.

- "Physio Montreal Article "Ultrasound"" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2003-03-09.

- Unsworth, A; Dowson, D; Wright, V (July 1971). "'Cracking joints'. A bioengineering study of cavitation in the metacarpophalangeal joint". Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 30 (4): 348–58. doi:10.1136/ard.30.4.348. PMC 1005793. PMID 5557778.

- Hauser-Gerspach, Irmgard; Vadaszan, Jasminka; Deronjic, Irma; Gass, Catiana; Meyer, Jürg; Dard, Michel; Waltimo, Tuomas; Stübinger, Stefan; Mauth, Corinna (August 13, 2011). "Influence of gaseous ozone in peri-implantitis: bactericidal efficacy and cellular response. An in vitro study using titanium and zirconia". Clinical Oral Investigations. 16 (4): 1049–1059. doi:10.1007/s00784-011-0603-2. ISSN 1432-6981. PMID 21842144. S2CID 10747305.

- "How The Food Industry Uses Cavitation, The Ocean's Most Powerful Punch". NPR.org. Retrieved 2017-12-13.

- "Application of Controlled Flow Cavitation in Oil & Fats Processing" (PDF). arisdyne systems. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-05-15. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- "US Patent for Methods for reducing soap formation during vegetable oil refining Patent (Patent # 10,968,414 issued April 6, 2021) - Justia Patents Search".

- "US Patent for Oil degumming systems Patent (Patent # 10,344,246 issued July 9, 2019) - Justia Patents Search".

- "US Patent for Method for degumming vegetable oil Patent (Patent # 9,845,442 issued December 19, 2017) - Justia Patents Search".

- "US Patent for Method for reducing neutral oil losses during neutralization step Patent (Patent # 9,765,279 issued September 19, 2017) - Justia Patents Search".

- Arisdyne Systems (April 27, 2012). "Hero BX adopts cavitation tech to reduce catalyst use, monos". Biodiesel Magazine. Retrieved 2022-05-19.

- "US Patent for Process for production of biodiesel Patent (Patent # 9,000,244 issued April 7, 2015) - Justia Patents Search".

- "US Patent Application for PROCESS FOR IMPROVED BIODIESEL FUEL Patent Application (Application #20100175309 issued July 15, 2010) - Justia Patents Search".

- Buckland, H. C.; Baker, T.; Orme, J. A. C.; Masters, I. (2013). "Cavitation inception and simulation in blade element momentum theory for modelling tidal stream turbines". Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part A: Journal of Power and Energy. 227 (4): 479–485. doi:10.1177/0957650913477093. S2CID 110248049.

- Fujisawa, Nobuyuki; Fujita, Yasuaki; Yanagisawa, Keita; Fujisawa, Kei; Yamagata, Takayuki (June 1, 2018). "Simultaneous observation of cavitation collapse and shock wave formation in cavitating jet". Experimental Thermal and Fluid Science. 94: 159–167. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2018.02.012. ISSN 0894-1777.

- Stachowiak, G.W.; Batchelor, A.W. (2001). Engineering tribology. Elsevier. p. 525. Bibcode:2005entr.book.....W. ISBN 978-0-7506-7304-4.

- Kelton, Sam (May 16, 2017). "Common Causes of Cavitation in Pumps". Triangle Pump Components. Archived from the original on 2018-07-16. Retrieved 2018-07-16.

- Golomb, Richard. "A new tailpipe design for GE frame-type gas turbines to substantially lower pressure losses". American Society of Mechanical Engineers. Retrieved 2012-08-02.

- Pulp & Paper (1992), Daishowa Reduces Pump Maintenance by Installing Fluid Rotating Vanes

- Emerson Process Management (2005), Control valve handbook, 4th Edition, page 136

- Vokart, P.; Rutschamnn, P. (1984). Kobus, H. (ed.). Rapid Flow in Spillway Chutes with and without Deflectors – A Model-Prototype Comparison. Proc. Intl. Symp. on Scale Effects in Modelling Hydraulic Structures, IAHR, Esslingen, Germany. paper 4.5.

- Peterka, A.J. (1953). "The Effect of Entrained Air on Cavitation Pitting". Joint Meeting Paper, IAHR/ASCE, Minneapolis, Minnesota, Aug. 1953. pp. 507–518.

- Chanson, H. (1989). "Study of Air Entrainment and Aeration Devices". Journal of Hydraulic Research. 27 (3): 301–319. Bibcode:1989JHydR..27..301C. doi:10.1080/00221688909499166. ISSN 0022-1686.

- Chanson, H. (1989). "Flow downstream of an Aerator. Aerator Spacing". Journal of Hydraulic Research. 27 (4): 519–536. Bibcode:1989JHydR..27..519C. doi:10.1080/00221688909499127. ISSN 0022-1686.

- Chanson, H. (June 1994). "Aeration and De-aeration at Bottom Aeration Devices on Spillways". Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering. 21 (3): 404–409. doi:10.1139/l94-044. ISSN 0315-1468.

- Chanson, H. (1995). "Predicting the Filling of Ventilated Cavities behind Spillway Aerators". Journal of Hydraulic Research. 33 (3): 361–372. Bibcode:1995JHydR..33..361C. doi:10.1080/00221689509498577. ISSN 0022-1686.

- Hawaiian Volcano Observatory (May 25, 2017). "Volcano Watch — Volcanoes, Landslides, and Angry Gods—A Pacific Northwest Connection". Volcano Watch. USGS. Retrieved 2017-05-28.

- Simakin, Alexander G.; Ghassemi, Ahmad (2018). "Mechanics of magma chamber with the implication of the effect of CO2 fluxing". In Aiello, Gemma (ed.). Volcanoes: Geological & Geophysical Setting, Theoretical Aspects & Numerical Modeling, Applications to Industry & Their Impact on the Human Health. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-7892-3348-3. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- Caupin, Frédéric; Herbert, Eric (2006). "Cavitation in water: a review". Comptes Rendus Physique. 7 (9–10): 1000–1017. Bibcode:2006CRPhy...7.1000C. doi:10.1016/j.crhy.2006.10.015.

- Sperry, J.S.; Saliendra, N.Z.; Pockman, W.T.; Cochard, H.; Cuizat, P.; Davis, S.D.; Ewers, F.W.; Tyree, M.T. (1996). "New evidence for large negative xylem pressures and their measurement by the pressure chamber technique". Plant Cell Environ. 19: 427–436. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3040.1996.tb00334.x.

- Noblin, X.; Rojas, N. O.; Westbrook, J.; Llorens, C.; Argentina, M.; Dumais, J. (2012). "The Fern Sporangium: A Unique Catapult" (PDF). Science. 335 (6074): 1322. Bibcode:2012Sci...335.1322N. doi:10.1126/science.1215985. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 22422975. S2CID 20037857. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-04.

- Brahic, Catherine (March 28, 2008). "Dolphins swim so fast it hurts". New Scientist. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- Iosilevskii, G; Weihs, D (2008). "Speed limits on swimming of fishes and cetaceans". Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 5 (20): 329–338. doi:10.1098/rsif.2007.1073. ISSN 1742-5689. PMC 2607394. PMID 17580289.

- Patek, Sheila. "Sheila Patek clocks the fastest animals". TED. Retrieved 2011-02-18.

- Tsikliras, Athanassios C.; Oliver, Simon P.; Turner, John R.; Gann, Klemens; Silvosa, Medel; D'Urban Jackson, Tim (2013). "Thresher Sharks Use Tail-Slaps as a Hunting Strategy". PLOS ONE. 8 (7): e67380. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...867380O. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0067380. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 3707734. PMID 23874415.

- Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "THRESHER SHARKS KILL PREY WITH TAIL". YouTube.

- Panizza, Mario (1996). Environmental Geomorphology. Amsterdam; New York: Elsevier. pp. 112–115. ISBN 978-0-444-89830-2.

- Euler (1754). "Théorie plus complete des machines qui sont mises en mouvement par la réaction de l'eau" [A more complete theory of machines that are set in motion by reaction against water]. Mémoires de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et Belles-Lettres (Berlin) (in French). 10: 227–295. See §LXXXI, pp. 266–267. From p. 266: "Il pourroit donc arriver que la pression en M devint même négative, & alors l'eau abandonneroit les parois du tuyau, & y laisseroit un vuide, si elle n'étoit pas comprimée par le poids de l'atmosphère." (It could therefore happen that the pressure in M might even become negative, and then the water would let go of the walls of the pipe, and would leave a void there, if it were not compressed by the weight of the atmosphere.)

- Besant, W. H. (1859). A Treatise on Hydrostatics and Hydrodynamics. Cambridge, England: Deighton, Bell, and Co. pp. 170–171.

- (University of Cambridge) (1847). "The Senate-house Examination for Degrees in Honors, 1847.". The Examinations for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts, Cambridge, January 1847. London, England: George Bell. p. 13, problem 23.

- Cravotto & Cintas (2012), p. 26.

- See:

- Reynolds, Osborne (1894). "Experiments showing the boiling of water in an open tube at ordinary temperatures". Report of the Sixty-fourth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science Held at Oxford in August 1894. 64: 564.

- Reynolds, Osborne (1901). "Experiments showing the boiling of water in an open tube at ordinary temperatures". Papers on Mechanical and Physical Subjects. Vol. 2. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 578–587.

- Thornycroft, John Isaac; Barnaby, Sydney Walker (1895). "Torpedo-boat destroyers". Minutes of the Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. 122 (1895): 51–69. doi:10.1680/imotp.1895.19693. From p. 67: " 'Cavitation,' as Mr. Froude has suggested to the Authors that the phenomenon should be called, … "

- Cravotto, Giancarlo; Cintas, Pedro (2012). "Chapter 2. Introduction to sonochemistry: A historical and conceptual overview". In Chen, Dong; Sharma, Sanjay K.; Mudhoo, Ackmez (eds.). Handbook on Applications of Ultrasound: Sonochemistry for Sustainability. Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press. p. 27. ISBN 9781439842072.

- Barnaby, Syndey W. (1897). "On the formation of cavities in water by screw propellers at high speeds". Transactions of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects. 39: 139–144.

- Parsons, Charles (1897). "The application of the compound steam turbine to the purpose of marine propulsion". Transactions of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects. 38: 232–242. The stroboscope is described on p. 234: "The screw [i.e., propeller] was illuminated by light from an arc lamp reflected from a revolving mirror attached to the screw shaft, which fell on it at one point only of the revolution, and by this means the shape, form, and growth of the cavities could be clearly seen and traced as if stationary."

- See:

- Parsons, Charles A. (1934) "Motive power — high-speed navigation steam turbines [address to the Royal Institution of Great Britain, delivered on 26 January 1900]". Parsons, G.L. (ed.). Scientific Papers and Addresses of the Hon. Sir Charles A. Parsons. Cambridge England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26–35.

- Parsons, Charles A. (1913). "Experimental apparatus shewing cavitation in screw propellers". Transactions - North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders. 29: 300–302.

- Richardson, Alexander (1911). Evolution of the Parsons Steam-Turbine. London, England: offices of "Engineering". pp. 72–76.

- Burrill, L.C. (1951). "Sir Charles Parson and Cavitation". Transactions of the Institute of Marine Engineers. 63: 149–167.

- Dryden, Hugh L.; Murnaghan, Francis D.; Bateman, H. (1932). "Report of the Committee on Hydrodynamics. Division of Physical Sciences. National Research Council". Bulletin of the National Research Council (84): 139.

- Rayleigh (1917). "On the pressure developed in a liquid during the collapse of a spherical cavity". Philosophical Magazine. 6th series. 34 (200): 94–98. doi:10.1080/14786440808635681.

- See, for example, (Rayleigh, 1917), p. 98, where, if P is the hydrostatic pressure at infinity, then a collapsing vapor bubble could generate a pressure as high as 1260×P.

- Stanley Smith Cook (1875–1952) was a designer of steam turbines. During the First World War, Cook was a member of a six-member committee that had been organized by the Royal Navy to investigate the deterioration ("erosion") of ship propellers. The erosion was attributed primarily to cavitation. See:

- "Erosion of propellers." Propeller Sub-Committee (Section III). Report of the Board of Invention and Research (September 17, 1917) London, England.

- Parsons, Charles A.; Cook, Stanley S. (1919). "Investigations into the causes of corrosion or erosion of propellers". Transactions of the Institution of Naval Architects. 61: 223–247.

- Parsons, Charles A.; Cook, Stanley S. (April 18, 1919). "Investigations into the causes of corrosion or erosion of propellers". Engineering. 107: 515–519.

- Gibb, Claude (November 1952). "Stanley Smith Cook. 1875-1952". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 8 (21): 118–127. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1952.0008. S2CID 119838312.; see pp. 123–124.

- Harrison, Mark (1952). "An experimental study of single bubble cavitation noise". Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 24 (6): 776–782. Bibcode:1952ASAJ...24..776H. doi:10.1121/1.1906978.

- Güth, Wernfried (1956). "Entstehung der Stoßwellen bei der Kavitation" [Origin of shock waves during cavitation]. Acustica (in German). 6: 526–531.

- Krehl, Peter O. K. (2009). History of Shock Waves, Explosions and Impact: A Chronological and Biographical Reference. Berlin and Heidelberg, Germany: Springer Verlag. p. 461. ISBN 9783540304210.

- Kornfeld, M.; Suvorov, L. (1944). "On the destructive action of cavitation". Journal of Applied Physics. 15 (6): 495–506. Bibcode:1944JAP....15..495K. doi:10.1063/1.1707461.

- Rattray, Maurice, Jr. (1951) Perturbation effects in cavitation bubble dynamics. Ph.D. thesis, California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, California, USA).

- Naudé, Charles F.; Ellis, Albert T. (1961). "On the mechanism of cavitation damage by nonhemispherical cavities in contact with a solid boundary" (PDF). Journal of Basic Engineering. 83 (4): 648–656. doi:10.1115/1.3662286. S2CID 11867895. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2018-07-24. Available at: California Institute of Technology (Pasadena, California, USA).

- Shipilov, S.E.; Yakubov, V.P. (2018). "History of technical protection. 60 years in science: to the jubilee of Prof. V.F. Minin". IOP Conf. Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing. 363 (12033): 012033. Bibcode:2018MS&E..363a2033S. doi:10.1088/1757-899X/363/1/012033.

Further reading

- For cavitation in plants, see Plant Physiology by Taiz and Zeiger.

- For cavitation in the engineering field, visit

- Kornfelt, M. (1944). "On the destructive action of cavitation". Journal of Applied Physics. 15 (6): 495–506. Bibcode:1944JAP....15..495K. doi:10.1063/1.1707461.

- For hydrodynamic cavitation in the ethanol field, visit and Ethanol Producer Magazine: "Tiny Bubbles to Make You Happy"

- Barnett, S. (1998). "Nonthermal issues: Cavitation—Its nature, detection and measurement;". Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 24: S11–S21. doi:10.1016/s0301-5629(98)00074-x.

- For Cavitation on tidal stream turbines, see Buckland, Hannah C; Masters, Ian; Orme, James AC; Baker, Tim (2013). "Cavitation inception and simulation in blade element momentum theory for modelling tidal stream turbines". Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part A: Journal of Power and Energy. 227 (4): 479. doi:10.1177/0957650913477093. S2CID 110248049.

External links

- Cavitation and Bubbly Flows, Saint Anthony Falls Laboratory, University of Minnesota

- Cavitation and Bubble Dynamics by Christopher E. Brennen

- Fundamentals of Multiphase Flow by Christopher E. Brennen

- van der Waals-type CFD Modeling of Cavitation

- Cavitation bubble in varying gravitational fields, jet-formation

- Cavitation limits the speed of dolphins

- Tiny Bubbles to Make You Happy

- Pump Cavitation Archived 2017-06-10 at the Wayback Machine