Cesspit

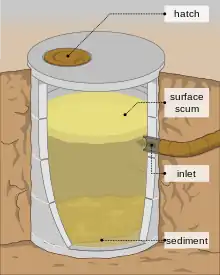

Cesspit, cesspool and soak pit in some contexts are terms with various meanings: they are used to describe either an underground holding tank (sealed at the bottom) or a soak pit (not sealed at the bottom).[1] A cesspit can be used for the temporary collection and storage of feces, excreta or fecal sludge as part of an on-site sanitation system and has some similarities with septic tanks or with soak pits. Traditionally, it was a deep cylindrical chamber dug into the ground, having approximate dimensions of 1 metre (3') diameter and 2–3 metres (6' to 10') depth. Their appearance was similar to that of a hand-dug water well.

The pit can be lined with bricks or concrete, covered with a slab and needing to be emptied frequently when it is used like an underground holding tank.[1] In other cases (if soil and groundwater conditions allow), it is not constructed watertight, to allow liquid to leach out (similar to a pit latrine or to a soak pit).

Uses

Holding tank

In the UK a cesspit is a closed tank for the reception and temporary storage of sewage; in North America this is simply referred to as a "holding tank". Because it is sealed, the tank must be emptied frequently – on average every 6 weeks[2] – but frequency varies a great deal and can be as often as weekly or as rarely as quarterly. Because of the need for frequent emptying, the cost of maintenance of a cesspit can be high. If owners in the UK do not maintain their cesspits they can be fined up to £20,000.[2]

Infiltration systems

A cesspool was at one time built like a dry well lined with loose-fitting brick or stone, used for the disposal of sewage via infiltration into the soil. Liquids leaked out through the soil as conditions allowed, while solids decayed and collected as composted matter in the base of the cesspool. As the solids accumulated, eventually the particulate solids blocked the escape of liquids, causing the cesspool to drain more slowly or to overflow.

A biofilm forms in the loose soil surrounding a cesspool or pit latrine that provides some degree of attenuation of the pollutants present, but a deep cesspool can allow raw sewage to directly enter groundwater with minimal biological cleansing, leading to groundwater pollution and undrinkable water supplies. It is for this reason that deep water wells on the property must be drilled far from the cesspool.

Most residential waste cesspools in use in the US today are rudimentary septic systems, consisting of a concrete-capped pit lined with concrete masonry units (cinder blocks) laid on their sides with perforated drain field piping (weeping tile) extending outward below the level of the intake connection. The concrete cover often has a cleanout pipe extending above ground. Some are constructed with concrete walls on one or more sides.

The waste cesspool is vulnerable to overloading or flooding by heavy rains or snow melt because it is not enclosed and sealed like conventional septic tank systems. It is also vulnerable to the entry of tree roots, which can eventually cause the system to fail.

Regulations

Modern environmental regulations either discourage or ban the use of cesspools, and instead connections to municipal sewage systems or septic tanks are encouraged or required.

In many countries, planning and development regulations for the protection of the watershed prevent home-owners who live close to rivers and environmentally sensitive areas from installing a septic system, requiring a holding tank instead.

United States

In some localities in the U.S., existing rural residential waste cesspools are "grandfathered", i.e. allowed to continue operations until they no longer function. Once defunct, they must be disconnected and replaced by modern septic systems. In areas that have a higher than usual water table or fail a percolation test, an above-ground drain field waste disposal system may be installed instead.

In the case of sale or transfer of residential property that uses an existing waste cesspool system, local laws may differ. Some counties or jurisdictions do not permit the sale of residential property that utilizes a waste cesspool. Other counties or villages may recognize the "grandfather clause" and allow the property sale or transfer with the cesspool.

History

United States

The typical American urbanite in the 1870s relied on the rural solution of individual well and outhouse (privy) or cesspools. Baltimore in the 1880s smelled "like a billion polecats" according to H. L. Mencken, and a Chicagoan said in his city "the stink is enough to knock you down." Improvement was slow, and large cities of the East and South depended to the end of the century mainly on drainage through open gutters. Pollution of water supplies by sewage as well as dumping of industrial waste accounted in large measures for the public health records and high mortality rates of the period. [3]

Europe

Cesspits were introduced to Europe in the 16th century, at a time when urban populations were growing at a faster rate than in the past. The added burden of waste volume began overloading urban street gutters, where chamber pots were emptied each day. There was no regulation of cesspit construction until the 18th century, when a need to address sanitation and safety concerns became apparent. Cesspits were cleaned out by tradesmen known in the UK as gongfermors using shovels and horse-drawn wagons. Cesspools were cleaned only at night, to reduce the smell and annoyance to the public. The typical cesspit was cleaned out once every 8 to 10 years. Fermentation of the solid waste collecting in cesspits, however, resulted in dangerous infections and gases that sometimes asphyxiated cesspit cleaners. Cesspits began to be cleaned out more regularly, but strict regulations for cesspit construction and ventilation were not introduced until the 1800s.[4]

Before construction reforms were introduced in the early 19th century, liquid waste would seep away through the ground, leaving solid waste behind in the cesspit. While this made removal of solid waste easier, the seeping liquid waste often contaminated well water sources, creating public health problems. Municipal reforms required that cesspits be built of solid walls of stone and concrete. This kept liquid waste in the cesspit, forcing cesspits to be cleaned more frequently, on average two or three times per year. Liquid cesspit waste would be removed with pumps by cesspit cleaners, and then solid waste, valuable as fertilizer and for manufacturing ammonia, was removed.[4]

In 1846, French public hygienist Alphone Guérard estimated that 100 cesspits were cleaned in Paris every night, by 200–250 total cesspit cleaners in the city, and out of a total of 30,000 cesspits. The replacement of Paris' cesspit system was challenged for decades by officials not on public hygiene grounds, but on economic ones, based on the desire to conserve human waste as fertilizer rather than disposing of it in a modern sewer system. Paris' sewer system began modernizing in the 1880s, with the conversion of storm sewers for public sewage. Some cesspits were still in use in Paris into the 20th century.[5]

Society and culture

Accidents

In Suffolk County, New York, most households still use cesspools for waste drainage.[6] Cesspool collapses have occurred in the area, for example on December 8, 2009, when two workers in a decommissioned cesspit were trapped, requiring a two-hour rescue mission. Since 1998, six cases have been reported of cesspools collapsing and sucking in human residents standing over them, injuring a total of seven people, and killing one in 2001,[7] one in 2007,[8] and one in 2010.[9]

On June 1, 2011, two teenagers, from the Suffolk County neighborhood of Farmingville, drowned after becoming overwhelmed by fumes and trapped in a backyard cesspool measuring 16 feet (4.9 m) deep.[10] Collapsing cesspools are mostly older ones, built with brick or cinder block. Those structures weakened over their lifespan leading to increased risk of collapse. Newer cesspools are made from precast concrete, which dramatically decreases the risk of collapse. All new construction in areas without sewerage systems use the new precast cesspools. In addition, cast concrete cesspools are used commonly in commercial construction, for storm water collection.

See also

References

- Tilley, E.; Ulrich, L.; Lüthi, C.; Reymond, Ph.; Zurbrügg, C. (2014). Compendium of Sanitation Systems and Technologies (2nd Revised ed.). Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology (Eawag), Duebendorf, Switzerland. ISBN 978-3906484570.

- "How Often Should Cesspit Emptying be Carried Out?". 2 January 2019.

- The National Experience.

- La Berge, Ann Elizabeth Fowler (2002). Mission and Method: The Early Nineteenth-Century French Public Health Movement. Cambridge University Press. pp. 207–09. ISBN 978-0521527019.

- La Berge, Ann Elizabeth Fowler (2002). Mission and Method: The Early Nineteenth-Century French Public Health Movement. Cambridge University Press. pp. 209, 215. ISBN 978-0521527019.

- John Derbyshire (2011-01-24), "Shovel Ready", The Straggler, National Review, 63 (1): 55, ISSN 0028-0038

- "Man, Son, Neighbor Sucked Into N.Y. Cesspool". Fox News. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- L.I. Landscaper Dies After Falling Into Cesspool Archived June 14, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Teen dies after falling into open cesspool outside of Long Island Dunkin' Donuts". nydailynews.com. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Two teens die after trapped in backyard cesspool on Long Island". Reuters. 2011-06-02. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Darvill, Timothy (2009), "cess pit", The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology, Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/acref/9780199534043.001.0001, ISBN 978-0199534043, retrieved 2020-04-23

- Greig, James. "The environmental archaeology of garderobes, sewers, cesspits and latrines". p. 1.

- "Cesspool". 25 February 2021.