Chaga people

The Chagga (Wachaga, in Swahili) are a Bantu ethnic group from Kilimanjaro Region of Tanzania. They are the third-largest ethnic group in Tanzania.[2] They historically lived in sovereign Chagga states on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro[3][4] in both Kilimanjaro Region and eastern Arusha Region.

Wachagga | |

|---|---|

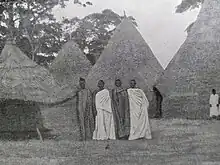

Mangi Meli of Moshi's Boma with traditional late 19th century Chagga aesthetic and architecture c.1890s | |

| Total population | |

| 800,000+ (1988 est.)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Chaga languages & Swahili | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity, Islam, African traditional religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Taita, Taveta, Pare, Shambaa people & other Bantu peoples |

| Person | Mchaga |

|---|---|

| People | Wachaga |

| Language | Kichaga |

| Country | Dchaga |

Being one of the most influential and economically successful peoples in Tanzania, their relative economic wealth comes from favorable fertile soil of Mount Kilimanjaro, industrious work ethic used in trading and successful agricultural methods, which include historic extensive irrigation systems, terracing, and continuous organic fertilization methods practiced for thousands of years from the time of the Bantu expansion, in their sovereign Chagga states.[5]

The location of Kilimanjaro means that, long before it was significant as a trading hub because of its location, the mountain served as an interim provisioning point in the commercial inland network. The residents of the mountain sold goods with caravans and traders from nearby settlements. It was easily accessible from the Swahili ports of Malindi, Takaungu, Mombasa, Wanga, Tanga, and Tangata as well as from Pangani in the south. Since they would cross Kilimanjaro on their way to conduct business in Pangani, the Kamba, Galla, and Nyamwezi are also familiar with the area. Chief Kivoi, a well-known Kamba trader, having personally climbed Kilimanjaro before organizing and leading his enormous caravans of up to 200 Kamba.[6]: 44

Etymology

The term "Dschagga" appears to have been first used to refer to a location rather than a group of people. Johannes Rebmann refers to "the inhabitants of the Dschagga" while describing the Taita and Kamba peoples on his first trip to the mountain. It appears that "Dschagga" was the general name given to the entire mountainous region by distant residents who had cause to describe it, and that when the European traveler arrived there, his Swahili guide used "Dischagga" to describe other portions to him in general rather than giving him specific names. For instance, Rebmann on his second and third journeys from Kilema to Machame speaks of "going to Dschagga" from Kilema. The word was anglicized to "Jagga" by 1860 and to "Chagga" by 1871. Because it used to be thought of by Swahillis as a perilous area to visit, Charles New chose the latter spelling and identified it as a Swahili name that meant "to stray" or "to get lost." This was beacuase of the dense forest around the mountain that confused visitors when they entered.[6]: 39

History

Origins

The Chagga are said to have descended from various Bantu groups who migrated from elsewhere in Africa to the foothills of Mount Kilimanjaro, a migration that began around the start of the eleventh century.[3] While the Chaga are Bantu-speakers, their language has a number of dialects somewhat related to Kamba, which is spoken in southeast Kenya.[3] One word they all have in common is Mangi, meaning 'king' in Kichagga.[7] The British called them chiefs as they were deemed subjects to the British crown, thereby rendered unequal.[8]

European travelers to Kilimanjaro in the late 19th and early 20th centuries questioned some Chagga kings about the origins of their respective clans and recorded the kings' responses in detail. For instance, Karl Peters was informed by Mangi Marealle of Marangu in the 1890s that the Wamarangu originated from Ukamba, the Wamoshi from Usambara, but that the Wakibosho had always been on the mountain. Peters also mentions that Capt. Kurt Johannes, a local serving German officer at the time, claimed that the Wakibosho were Maasai descendants.[9]

Those claimed that some of them were of Maasai, Usambara, and Kamba origins, very Few mangis of today would claim that, including those of the oldest clans, who are proud of their long history that predates the arrival of those who would later become the royal clans, claim that their royal clan originated on the mountain from a particular other location or admit to having blood other than Chagga. Given that acknowledging one's origins may be perceived as undermining the Chagga's historical claim to the land. Alternatively, it's possible that those early interrogators by the Europeans were oversimplified the responses they received or used leading questions to be more precise.[9]

In Chaggaland today, oral traditions are clear as to when a branch of a clan split off and moved to live elsewhere on the volcano, but that branch itself hardly ever acknowledges where it came from and its history begins with the founding of the branch in its new land; it's possible that by a similar process, clan histories naturally start with the ancestors' arrival on Kilimanjaro. Ex-Mangi Lemnge of Mamba, for instance, is perculiar in today's society because he claims to be of mixed Chagga and Masai heritage and is married to a wife who is of mixed Chagga and European stock, making their children one of the mountain's most intriguing minglings. Although Orombo's descendants dispute this, some Chagga claim that the legendary chief of the past, Orombo of Keni (now a portion of Keni-Mriti-Mengwe), was of Maasai descent. A fascinating local legend claims that a Masai tribe from the west entered Kibongoto, divided their clan, and sent their sons to various regions of the mountain, where they all rose to the position of mangi.[9]

The histories of each Chagga state contain clues as to which clans sprang "from the mountain," which were "dropped there," which originated on the plains, or traveled in an easterly or westerly manner. Quite a bit of Chaggaland is still unknown, especially up in the high forest where the remains of ancient shrines are found and where it is rumored that plantings of masale, the sacred Chagga plant, indicate the paths that small people, or pygmies, long ago traveled. The ruins of stone-wall enclosures lie unexplored in the upper mitaa's rocky parts; they may well add to our understanding of the larger, more accessible enclosures on the middle slopes of certain chiefdoms. When the Chagga traveled here in the past, they used caves on the high track that circles the back of the mountain for shelter, but we are unsure of their exact purpose at this time.[9]

The vast belt of wild olives that come out of nowhere in the forest on the bare northern side of the mountain is one tree that has not yet been well examined. It is possible that this land was once cleared and inhabited by Chagga because, per a silviculturalist's theory, the Kilimanjaro forest regenerates itself using olive trees. It is plausible that the forebears who are so frequently claimed to have "come from the mountain" actually originated on this north side before moving to where their descendants currently live on the south side.[9]

Language, physiognomy, custom, and house-making conceal more clues. The Kichagga language is evolving so quickly that to the Chagga of today, the language as it was used even 20 years ago sounds practically "classical." This is due in part to natural factors, such as the acquisition of new words, and in part to factors related to political authority, such as how Machame in the west and Marangu in the middle zone each disseminated their respective standard languages among the chiefdoms nearby. However, remnants of ancient, undeveloped settlement in some parts of the upper mitaa still maintain their distinctive dialects of Kichagga, and, most remarkably and productively for linguistic research, Ngasseni (now a part of Usseri) continues to speak a language that is distinctly distinct from Kichagga and virtually unintelligible to others in the same kingdom.[9]

Similar origin indicators can be found in customs exclusive to particular clans or mitaa. In the mitaa of the ancient Samake, Nguni, and Kyuu, a special kind of cursing stone was employed, and there was fire worship that seemed to be older, different, and more magical than the fire ceremonies that the Usambaras introduced into Kibosho; in Kahe, male and female clay idols were made and were used for cursing by the Arusha Chini folk; and the ancient Mtui clan of Marangu maintained its power. The fact that the first ancestors arrived with a variety of tools—sometimes bows and arrows, sometimes spears—and that clan memories preserve whether they were hunters, livestock keepers, or cultivators may be crucial.[9]

This type holds clues to the farther past. Zones of widespread custom gradually grew out of this. In general, the similarities in customs and spoken Kichagga dialects across the entire central stretch of chiefdoms, from the Weru Weru River on the west to the Mriti hills on the east, served as a unifying force. When one crossed the Weru Weru in the west or the Mriti hills in the east, a significant difference emerged. All the while, circumcision was practiced. Initiation, however, was a peculiar blossoming in the center zone and involved teaching tribal lore using symbols carved on a special stick (Kich. mregho) and secret terms of speaking for use in the face of foes (Kich. ngasi).[9]

East of this zone, a type of mregho is found in Ngasseni, and a very simple variety is found in Mkau. West of this zone, as will be seen, there is oral evidence to suggest that initiation was introduced and then abandoned as a political act to forestall reprisals in one of the major inter-chiefdom feuds on the mountain. At the Weru Weru basin, the method of building houses begins to change: east of it, the round beehive houses are thatched from top to bottom; west of it, they are increasingly built with roofs starting at a four-foot spring from the ground, so that moving west from Kilimanjaro, through Meru and Arusha, the houses more and more resemble the bomas of the Maasai. The dwellings in Moshi Chiefdom are a hotch-potch of architectural styles, some with roofs that are four feet off the ground and others that are higher than anywhere else in the mountain.[9]

According to outside evidence, many Chagga originated mostly in the northeastern region. While some did so, possibly particularly when the Galla were migrating from the north and pressing people in general before them, it appears more likely that the journey was a natural one. On the borders of Chaggaland, the Masai moved into the western, the Pare into the central zones, and Kikuyu squatters moved into the north side of the mountain until they were evicted as a result of Mau Mau troubles in 1954. Kamba and Masai move in naturally today into the eastern areas, the former to settle and the latter to graze. People used to come from the north, coming from Taita and the Kamba hills; the east, coming from the Usambaras; and the south, maybe coming from Unyamwezi and the Nguu highlands.[9]

Another factor supporting the idea that the arrival of people from the northeast may merely be a broad generalization is the fact that other East African tribes in the Kilimanjaro region have a history of ascending from the south, driving others north before them. According to legend, some Kamba left their former home on Kilimanjaro and went up from the south. For instance, the Kamba are supposed to have been forced up from Shikiani to avoid the Wadoe tribes, who were allegedly cannibalistic. Additionally, some Wanika has left their ancestral home in Rombo, Chaggaland, and moved from the southwest. According to Chagga ora legends, some Meru arrived from the east from their resting spot en route to Mount Meru.[10]

According to legend, the Usambara Kilindi dynasty came up from the Nguu Mountains in the south. The idol that Krapf discovered the coastal Wanika using may have originated in Kahe. The Wanika is reported to have departed Kilema, traveled to Rombo, and then moved to the coast. For further information, see von der Decken's description of this Wanika emigration to the coastal regions behind Mombasa, which he attributes to the rule of Munie Mkoma (Mangi Rongoma) of Kilema.[10]

Other clues can be discovered in the routes traveled by those who, according to Chagga oral traditions, crossed Kilimanjaro, including pygmies or "little people," those who are remembered as being distinct from Chagga and having thick necks, and Swahilis. According to legend, the pygmies (Kich. Wakoningo) crossed the mountain from east to west before continuing to the Congo Basin. Although there is a story found only in Uru about similarly unique visitors who traveled from the opposite direction, from the west, in search of lumber for King Solomon, the little people did move from east to west across the mountain.[10]

The Ongamo had a large effect on Chaga culture. They borrowed several practices from them, including female circumcision, the drinking of cattle blood, and age sets. By the second half of the nineteenth century, the Ongamo were increasingly acculturated into the Chaga. The Chaga god "Ruwa" resulted from the combination of the Chaga's concept of a creator god with the Ongamo's concept of the life giving sun.[3]

The following are very tenuous, unproven signs that the "little" people were Portuguese: the straightforward ascent from the coast; the closeness of Ngeruke; the ironworks of Koyo reached via Kilimanjaro by Bwana Kheri; the male and female idols, still made in Kahe today and still used for magic by the Arusha Chini folk, who bring them upon request, for cursing as far as Arusha Juu (the modern Arusha). According to the King Solomon account recorded in Uru, this tradition is an old one that dates back to the period before people moved from Arusha Chini to Arusha Juu.[10] Regarding the breastwork between Kilema and Usseri, it is possible that Bwana Kheri was referring to the three adjacent large stone-wall enclosures, or fortresses, that Mangi Orombo had constructed in Keni, the mountain's first structure of this scale. However, we don't know if Orombo built on top of earlier traces left by others, possibly the Portuguese.[10]

Munie Mkoma from Pangani, who may have begun the tradition if Mangi Rongoma of Kilema was a Swahili, may have been the original. A line of comparable connections in many chiefdoms was started by Mangi Mamkinga of Machame's confidence in his resident Swahili Munie Nesiri four generations later, in 1848. These signs seem to indicate that the Chagga's origins are more complicated than those of the Taita, who, in response to Rebmann's inquiry, stated that they had traveled thirty days north.[10]

The Pare, Taveta, and Taita peoples had been the chief suppliers of iron to the Chaga.[3] The demand for iron increased from the beginning of the nineteenth century because of military rivalries among the Chaga rulers.[3] It is likely that there was a connection between this rivalry and the development of long-distance trade from the coast to the interior of the Pangani River basin, suggesting the Chagga's contacts with the coast may have dated to about the end of the eighteenth century.

The development of numerous Chagga countries, as well as the sum of their histories, is one of Kilimanjaro's internal histories. Because each of the mitaa or parishes of today—there are over 100 of them—represents the amalgamation of two or three former mitaa, long-established independent units of earlier periods, with the exception of new territories recently opened up on the western and eastern wings and on the lower mountain slopes. In the minds of the elderly Chagga, these are still actual living things.[10] The Chagga states, which by 1964 numbered fifteen, are what old men mean when they refer to "the countries of Kilimanjaro"; yet, inside each chiefdom, each old mtaa is referred to as a "country" when they speak of the past.[10]

In this pre-colonial world of the past, one enters, there were fewer Chagga people, more land was available, and distances were vast in comparison to the world of Kilimanjaro, which has decreased due to the advent of the modern truck, bus, and motorcar. Over a major portion of Kilimanjaro, however, the pace of the human foot is still used to measure distance.[10]

.jpg.webp)

_of_the_Chaga_people.jpg.webp)

Chaggaland

The Chaggaland is traditionally divided into a number of small kingdoms known as Umangi. They follow a patrilineal system of descent and inheritance.[3] Their traditional way of life was based primarily on agriculture, using irrigation on terraced fields and oxen manure. Although bananas are their staple food, they also cultivate various crops, including yams, beans, and maize. In agricultural exports, they are best known for their Arabica coffee, which is exported to the global market, resulting in coffee being a primary cash crop.

By 1899 the Kichagga-speaking people on Mount Kilimanjaro were divided into 37 autonomous kingdoms called "Umangi" in Chaga languages.[11] Early accounts frequently identify the inhabitants of each kingdom as a separate "tribe." Although the Chaga are principally located on Mount Kilimanjaro in northern Tanzania, numerous families have migrated elsewhere over the course of the twentieth century. In 1946 the British administration had greatly reduced the number of kingdoms due to large scale reorganization and creation of newly settled land on the lower slopes on the western and eastern slopes of Kilimanjaro.[5]

Around the beginning of the twentieth century, the German colonial government estimated that there were about 28,000 households on Kilimanjaro.[11] In 1988, the Chaga population was estimated at over 800,000 individuals.[1]

The Chagga Homestead

Much of the Chagga lifestyle was shaped by their earth based and ancestral veneration based religious beliefs. Before the arrival of Christianity and Islam, the Chaga practiced a diverse range of faith with a thoroughgoing syncretism.[11] The importance of ancestors is strongly maintained by them to this day. The name of the chief Chaga deity is Ruwa who resides on the top of Mount Kilimanjaro, which is sacred to them. Parts of the high forest contain old shrines with masale plantings, the sacred Chaga plant.[6]

Chagga legends centre on Ruwa and his power and assistance. 'Ruwa' is the Chagga name for their god in Eastern and Central Kilimanjaro, while in the Western region, especially Machame and Masama, the deity was referred to as 'Iruva.' Both names are also Chaga words for "sun."[12] Ruwa is not looked upon as the creator of humankind, but rather as a liberator and provider of sustenance. He is known for his mercy and tolerance when sought by his people.

Every single family lives in the seclusion of their fenced-in farmhouse, or kihamba in Kichagga, even in the most crowded sections of Chaggaland. Each home is surrounded by the Masale plant, a revered symbol of peace and forgiveness in the Chagga culture (Dracaena fragrans). It contains a banana grove, with its long, overhanging fronds shading tomatoes, onions, and various varieties of yam. In the middle of the grove is a round, beehive-shaped house made of mud and covered in grass or banana leaves. The husband's hoe and other equipment can be stored in the sleeping quarters, which can be either a hide or a bed and is close to the door. A fire is burning in the middle of the room, supported by three stones, and bananas are drying in a little loft above the fire.[13][6]: 27

A blacksmith may be seen hunched over hot embers with his anvil and goatskin bellows in some homesteads, while a woman shaping and firing earthen pots is more infrequently seen in others. Beehives made of hollowed-out tree trunk lengths with stoppers are hung from the trees outside, and hides are stretched on pegs to dry at the door.[6]: 27

Typically, neighbors come from the same clan. Interior paths connect the homesteads in the region controlled by that clan, and the entire area is separated from the neighboring homes of the next clan by a larger hedge or an earth bank. A mtaa is made up of numerous clans, and a mtaa is made up of several clans. When Rebmann arrived in Kilema in 1848, he immediately remarked on the order that had taken hold due to the mangi's firm authority. He was enthralled by the prosperity and abilities of the populace, as well as by the pleasant weather and natural beauty of the area.[6]: 27

Notable Chagga

Royal figures

- Ngalami, Mangi of Siha

- Mangi Meli, Mangi of Moshi

- Mangi Rengua, Mangi of Machame

Religious figures

- Jude Thaddaeus Ruwa'ichi, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Dar es Salaam

- Henry Rimisho, Roman Catholic priest, Academician

- Isaac Amani Massawe, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Arusha

- Amedeus Msarikie, Former Roman Catholic Bishop of Moshi

- Joseph Sipendi, Former Roman Catholic Bishop of Moshi

- Prosper Balthazar Lyimo, Roman Catholic Auxiliary Bishop of Arusha

Politicians

- Jackson Kitali, politician

- Elifuraha Marealle , Politician

- Lucy Lameck, first female Tanzanian Minister Tanganyika African National Union

- Asanterabi Zephaniah Nsilo Swai - Tanganyika African National Union

- Edwin Mtei – CHADEMA

- Augustine Mrema – TLP & CCM

- James Mbatia - NCCR-MAGEUZI

- Godbless Lema-CHADEMA

- Freeman Mbowe - CHADEMA

- Basil Mramba - CCM

- Adolf Mkenda - CCM

- Hassan Mtenga - CCM

- Abubakar Asenga - CCM

- Cyril Chami - CCM

- Salome Joseph Mbatia - CCM

- Saasisha Mafuwe - CCM

- Aggrey Mwanri - CCM

Academics and writers

- Nathaniel Mtui, First published Tanzanian historian.

- Leonard Shayo, Tanzanian mathematician and former presidential candidate

- Irene Tarimo, Tanzanian academic lecturer, researcher, biologist and env. scientist

- Adolf Mkenda, Tanzanina academic professor and politician CCM's MP

- Elizabeth Mrema, Tanzanian Biodiversity leader and attorney

- Andrew Tarimo, Tanzanian Irrigation Expert

- Fausta Shakiwa Mosha, Tanzanian Scientist

- Rodrique Msechu, Tanzanian Entrepreneur

- Khalila Mbowe, Tanzanian choreographer

- Doreen Kessy, Tanzanian author and educator

- Ruth Meena, Tanzanian Academic and Gender Activist

- Elieshi Lema, Tanzanian Writer and Publisher

- Frannie Leautier, Tanzania civil engineer and academic

- Felix A. Chami, Tanzanian academic and Archaeologist

- Sandra A. Mushi, Tanzanian writer

Statespeople

- Augustine Saidi, First Tanzanian Chief Justice

- Helen Kijo-Bisimba, Tanzanian human rights activist

- John Mrosso, Tanzanian Judge

- Robert Kisanga, Tanzanian Judge

Businesspeople

- Reginald Mengi - Tanzanian business tycoon and multi millionaire.

- Chrispine Mlingi - Tanzanian business tycoon and multi millionaire.

- Michael Shirima, Tanzanian business owner.

- Patrick E. Ngowi, Tanzanian business owner.

- Julia Lang (fashion entrepreneur), German Tanzanian creative director and entrepreneur

.jpg.webp)

Sportspeople

- Leodgar Tenga - Tanzanian Football player (Former President of Tanzania Football Federation)

- Farid Musa - Tanzanian Football player

- Bruno Tarimo - Tanzanian boxer

- Haruna Moshi - Tanzanian footballer

- Hassan Kessy - Tanzanian footballer

- Amani Kyata - Tanzanian footballer

- Magdalena Moshi - Tanzanian Olympic swimmer

- William Lyimo - Tanzanian boxer

- Wilfred Moshi - First Tanzanian to summit Mount Everest[14]

- Michael John Lema, Tanzania-Austrian professional footballer

Entertainers and artists

- Bruno Tarimo, Professional Boxing athlete

- Master J, Tanzanian music producer

- Bill Nass, Tanzanian musician

- Joh Makini, Tanzanian iconic rapper

- Elizabeth Michael Lulu- Tanzanian actress

- Jacqueline Wolper, Tanzanian actress

- Hoyce Temu, Tanzanian beauty pageant winner

- Rosa Ree (rapper), Tanzanian female rapper

- Amani Temba, Tanzanian musician

- Sheria Ngowi, Tanzanian fashion designer

- Aika Marealle, Navy Kenzo Tanzanian singer and songwriter

- Barnaba Classic, Tanzanian singer and songwriter

- Lucas Mkenda, a Tanzanian Musician

- Francisca Urio, German-Tanzanian Musician

- Cherry (Tanzanian singer), Tanzanian singer and actress

See also

References

- "Tanzania -- Ethnic Groups". East Africa Living Encyclopedia. University of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- Levinson, David (5 July 1998). Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook. Oryx Press. ISBN 9781573560191 – via Google Books.

- Shoup, John A. (2011). Ethnic Groups of Africa and the Middle East: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 67. ISBN 9781598843637.

- Yonge, Brian. "The rise and fall of the Chagga empire." Kenya Past and Present 11.1 (1979): 43-48.

- Oliver, R. A. (November 1964). "The Chagga and Their Chiefs. Reviewed Work: History of the Chagga People of Kilimanjaro by Kathleen M. Stahl, 1964". The Journal of African History. 5 (3): 462–464. doi:10.1017/s0021853700005181. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 245908751.

- Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- Bender, Matthew V. "BEING ‘CHAGGA’: NATURAL RESOURCES, POLITICAL ACTIVISM, AND IDENTITY ON KILIMANJARO." The Journal of African History, vol. 54, no. 2, 2013, pp. 199–220. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43305102. Accessed 11 Apr. 2023.

- "Chagga people- history, religion, culture and more". United Republic of Tanzania. 2021. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. pp. 51–53. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- Stahl, Kathleen (1964). History of the Chagga people of Kilimanjaro. London: Mouton and Co. pp. 54−56. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- "Chagga facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Chagga". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- Spear, Thomas T.; Kimambo, Isaria N. (1999). East African Expressions of Christianity. James Currey. pp. 40–52. ISBN 978-0-8214-1273-2.

- Cleveland, David A.; Soleri, Daniela (1987). "Household Gardens as a Development Strategy". Human Organization. 46 (3): 259–270. doi:10.17730/humo.46.3.m62mxv857t428153. ISSN 0018-7259. JSTOR 44126174. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- "Nature Discovery Guide Wilfred Moshi Summits Mt. Everest!". Nature Discovery Tanzania. 7 June 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

Further reading

- Ehret, Christopher (2002). The Civilizations of Africa. University of Virginia Press. ISBN 0-8139-2085-X.

- Gray, R (1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20413-5.

- Fasi, M El (1992). Africa from the Seventh to the Eleventh Century. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-06698-7.

- Johnson, H.H (1886). "Copyright: Tubner & Co". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. XV: 12–14.

- Yakan, Mohamad A (1999). Almanac of African Peoples & Nations. Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-433-9.

- P. H. Gulliver (1969). Tradition and Transition in East Africa: Studies of the Tribal Element in the Modern Era. University of California Berkeley.