Chagos Archipelago

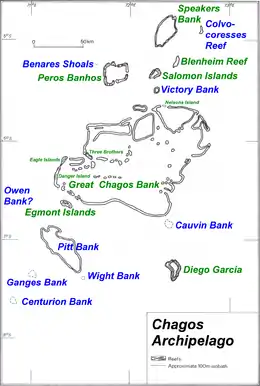

The Chagos Archipelago (/ˈtʃɑːɡəs, -ɡoʊs/) or Chagos Islands (formerly the Bassas de Chagas,[2] and later the Oil Islands) is a group of seven atolls comprising more than 60 islands in the Indian Ocean about 500 kilometres (310 mi) south of the Maldives archipelago. This chain of islands is the southernmost archipelago of the Chagos–Laccadive Ridge, a long submarine mountain range in the Indian Ocean.[3] In its north are the Salomon Islands, Nelson's Island and Peros Banhos; towards its south-west are the Three Brothers, Eagle, Egmont and Danger Island(s); southeast of these is Diego Garcia, by far the largest island. All are low-lying atolls, save for a few extremely small instances, set around lagoons.

| Disputed islands | |

|---|---|

Map of the Chagos Archipelago | |

Location of the Chagos Archipelago (circled) | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Indian Ocean |

| Coordinates | 6°00′S 71°30′E |

| Major islands | Diego Garcia, Peros Banhos, Salomon Islands, Egmont Islands |

| Area | 56.13 km2 (21.67 sq mi) |

| Administration | |

| Territory | |

| Claimed by | |

| Outer Islands | |

| Demographics | |

| Demonym | Chagossian Chagos Islander |

| Population | ≈3,000 (Eclipse Point Town) (2014) |

| Ethnic groups | |

The Chagos Islands had been home to the Chagossians from the 1700s brought as workers by the French from Africa and India, a Bourbonnais Creole-speaking people, until the United Kingdom expelled them from the archipelago at the request of the United States between 1967 and 1973 to allow the United States to build a military base on Diego Garcia. Since 1971, only the atoll of Diego Garcia has been inhabited, and only by employees of the US military, including American civilian contracted personnel. Since being expelled, Chagossians, like all others not permitted by the UK or US governments, have been prevented from entering the islands.

When Mauritius was a French colony, the islands were a dependency of the French administration in Mauritius (Île Maurice). By the Treaty of Paris of 1814, France ceded Mauritius and its dependencies to the United Kingdom.

In 1965, while planning for Mauritian independence the UK constituted the Chagos as the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT).[4][5] Mauritius gained independence from the United Kingdom in 1968, and has since claimed the Chagos Archipelago as Mauritian territory.

In 2019, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) issued a non-binding advisory opinion stating that the UK "...has an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible, and that all Member States must co-operate with the United Nations to complete the decolonization of Mauritius".[6] In December of that year, the Sega tambour Chagos genre was recognized as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage from Mauritius.[7] In January 2021, the United Nations General Assembly approved a resolution proclaiming this.[8] In 2021, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea confirmed for its jurisdiction that the UK has "no sovereignty over the Chagos Islands" thus the islands should be handed back to Mauritius.[8][9]

In August 2021, the Universal Postal Union banned British stamps from being used in BIOT, a move Mauritian Prime Minister Pravind Jugnauth called a "big step in favour of the recognition of the sovereignty of Mauritius over the Chago".[10]

Geography

(Atolls with areas of dry land are named in green)

The archipelago is about 500 kilometres (310 mi) south of the Maldives, 1,880 kilometres (1,170 mi) east of the Seychelles, 1,680 kilometres (1,040 mi) north-east of Rodrigues island, 2,700 kilometres (1,700 mi) west of the Cocos (Keeling) Islands, and 3,400 kilometres (2,100 mi) north of Amsterdam Island.

The land area of the islands is 56.13 km2 (21.7 sq. miles), the largest island, Diego Garcia, having an area of 32.5 km2. The total area, including lagoons within atolls, is more than 15 000 km2, of which 12 642 km2 are accounted by the Great Chagos Bank, the largest acknowledged atoll structure of the world (the completely submerged Saya de Malha Bank is larger, but its status as an atoll is uncertain). The shelf area is 20 607 km2, and the Exclusive Economic Zone, which borders the corresponding zone of the Maldive Islands in the north, has an area of 639 611 km2 (including territorial waters).

The Chagos group is a combination of different coralline rock structures topping a submarine ridge running southwards across the centre of the Indian Ocean, formed by volcanoes above the Réunion hotspot. Unlike the Maldives, there is no clearly discernible pattern in the atoll arrangement, which makes the whole archipelago look somewhat chaotic. Most of the coralline structures of the Chagos are submerged reefs.

The Chagos contain the world's largest coral atoll, The Great Chagos Bank, which supports half the total area of good quality reefs in the Indian Ocean. As a result, the ecosystems of the Chagos have so far proven resilient to climate change and environmental disruptions.

The largest individual islands are Diego Garcia (32.5 km2), Eagle (Great Chagos Bank, 3.1 km2), Île Pierre (Peros Banhos, 1.40 km2), Eastern Egmont (Egmont Islands, 2.17 km2), Île du Coin (Peros Banhos, 1.32 km2) and Île Boddam (Salomon Islands, 1.27 km2).

In addition to the seven atolls with dry land reaching at least the high-water mark, there are nine reefs and banks, most of which can be considered permanently submerged atoll structures. The number of atolls in the Chagos Archipelago is given as four or five in most sources, plus two island groups and two single islands, mainly because it is not recognised that the Great Chagos Bank is a huge atoll structure (including those two island groups and two single islands), and because Blenheim Reef, which has islets or cays above or just reaching the high-water mark, is not included. Features are listed in the table from north to south:

| Atoll/Reef/Bank (alternate name) | type | Area (km2) | number of islands | Location | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Land | Total | |||||||

| 0 | unnamed bank | submerged bank | – | 3 | – | 04°25′S 72°36′E | ||

| 1 | Colvocoresses Reef | submerged atoll | – | 10 | – | 04°54′S 72°37′E | ||

| 2 | Speakers Bank | unvegetated atoll | 0.001 | 582 | 1) | 04°55′S 72°20′E | ||

| 3 | Blenheim Reef (Baixo Predassa) | unvegetated atoll | 0.02 | 37 | 4 | 05°12′S 72°28′E | ||

| 4 | Benares Shoals | submerged reef | – | 2 | 05°15′S 71°40′E | |||

| 5 | Peros Banhos | atoll | 9.6 | 503 | 32 | 05°20′S 71°51′E | ||

| 6 | Salomon Islands | atoll | 3.56 | 36 | 11 | 05°22′S 72°13′E | ||

| 7 | Victory Bank | submerged atoll | – | 21 | – | 05°32′S 72°14′E | ||

| 8a | Nelson Island | parts of mega-atoll Great Chagos Bank | 0.61 | 12642 | 1 | 05°40′53″S 72°18′39″E | ||

| 8b | Three Brothers (Trois Frères) | 0.53 | 3 | 06°09′S 71°31′E | ||||

| 8c | Eagle Islands | 3.43 | 2 | 06°12′S 71°19′E | ||||

| 8d | Danger Island | 1.06 | 1 | 06°23′00″S 71°14′20″E | ||||

| 9 | Egmont Islands | atoll | 4.52 | 29 | 7 | 6°40′S 71°21′E | ||

| 10 | Cauvin Bank | submerged atoll | – | 12 | – | 06°46′S 72°22′E | ||

| 11 | Owen Bank | submerged bank | – | 4 | – | 06°48′S 70°14′E | ||

| 12 | Pitt Bank | submerged atoll | – | 1317 | – | 07°04′S 71°21′E | ||

| 13 | Diego Garcia | atoll | 32.8 | 174 | 42) | 07°19′S 72°25′E | ||

| 14 | Ganges Bank | submerged atoll | – | 30 | – | 07°23′S 70°58′E | ||

| 15 | Wight Bank | 3 | 07°25′S 71°31′E | |||||

| 16 | Centurion Bank | 25 | 07°39′S 70°50′E | |||||

| Chagos Archipelago | Archipelago | 56.13 | 15427 | 64 | 04°54' to 07°39'S 70°14' to 72°37' E | |||

| 1) a number of drying sand cays | ||||||||

| 2) main island and three islets at the northern end | ||||||||

Resources

The main natural resources of the area are coconuts and fish. The licensing of commercial fishing used to provide an annual income of about US$2 million for the British Indian Ocean Territory authorities. However, licenses have not been given since October 2010; the last expired after the creation of the no-take marine reserve.[11]

All economic activity is concentrated on the largest island of Diego Garcia, where joint UK–US military facilities are located. Construction projects and various services needed to support the military installations are done by military and contract employees from the UK, Mauritius, the Philippines, and the US. There are currently no industrial or agricultural activities on the islands. All the water, food and other essentials of daily life are shipped to the island. An independent feasibility study led to the conclusion that resettlement would be "costly and precarious". Another feasibility study, commissioned by organisations supporting resettlement, found that resettlement would be possible at a cost to the British taxpayer of £25 million. If the Chagossians return, they plan to re-establish copra production and fishing, and to begin the commercial development of the islands for tourism.

Until October 2010, Skipjack (Euthynnus pelamis) and yellowfin tuna (Thunnus albacares) were fished for about two months of the year as their year-long migratory route takes them through Chagos waters. While the remoteness of the Chagos offers some protection from extractive activities, legal and illegal fishing have had an impact. There is considerable poaching of turtles and other marine life. Sharks, which play a vital role in balancing the food web of tropical reefs, have suffered sharp declines from illegal fishing for their fins and as bycatch in legal fisheries. Sea cucumbers, which cleanse sand, are poached to feed Asian markets.

Climate

The Chagos Archipelago has a tropical oceanic climate; hot and humid but moderated by trade winds. Climate is characterised by plenty of sunshine, warm temperatures, showers and light breezes. December through February is considered the rainy season (summer monsoon); typical weather conditions include light west-northwesterly winds and warmer temperatures with more rainfall. June to September is considered the drier season (winter), characterised by moderate south-easterly winds, slightly cooler temperatures and less rainfall. The annual mean rainfall is 2 600 mm (100 inches), varying from 105 mm (4 inches) during August to 350 mm (14 inches) during January.

History

Early history

According to Southern Maldivian oral tradition, local traders and fishermen were occasionally lost at sea and became stranded in one of the islands of the Chagos. Eventually they were rescued and brought back home.[12] However, these islands were judged to be too far away from the Maldives to be settled permanently by Maldivians. Thus for many centuries the Chagos were ignored by their northern neighbours.

In Maldivian lore the whole group is known as Fōlhavahi or Hollhavai (the latter name in the Southern Maldives Adduan dialect of Dhivehi). There are no separate names for the different atolls of the Chagos in the Maldivian oral tradition. The Archipelago as a whole, Maldivians say "Fayhandheeb". According to maldivian history, Maldives Archipelago consists of Mahaldheeb, Suvaadheebu and Feyhandheeb. [13]

16th to 19th century

The first Europeans to become aware of the archipelago were Portuguese explorers. Although the Portuguese navigator Pedro de Mascarenhas (1470 – 23 June 1555) is credited with having encountered the islands during his voyage of 1512–13, there is little corroborative evidence; cartographic analysis points to 1532 or later. Portuguese seafarers named the group Bassas de Chagas,[14] Portuguese: Chagas (wounds) referring to the Holy Wounds of the crucifixion of Jesus. They also named some of the atolls, such as Diego Garcia and Peros Banhos Atoll, mentioned as Pedro dos Banhos in 1513 by Afonso de Albuquerque.[15] This lonely and isolated group, economically and politically uninteresting to the Portuguese, was never made part of the Portuguese Empire.[16]

The earliest and most interesting description of the Chagos, before coconut trees grew widely on the islands, was written by Manoel Rangel, a castaway from the Portuguese ship Conceição which ran aground on the Peros Banhos reefs in 1556.[17]

The French were the first to lay claim to the Chagos after they settled Île Bourbon (now Réunion, in 1665) and Isle de France (now Mauritius, in 1715). The French began issuing permits for companies to establish coconut oil plantations on the Chagos in the 1770s.[18]

On 27 April 1786 the Chagos Islands and Diego Garcia were claimed for Great Britain. However, the territory was ceded to Britain by treaty only after Napoleon's defeat, in 1814. The Chagos were governed from Mauritius, which was by that time also a British colony.[19]

In 1793, when the first successful colony was founded on Diego Garcia, the largest island, coconut plantations were established on many of the atolls and isolated islands of the archipelago. The workers were enslaved by the British and not freed until 1840, after which time many of the workers descended from those who had earlier been enslaved. They formed an inter-island culture called Ilois, a French Creole word meaning "Islanders".

Commander Robert Moresby made a survey of the Chagos on behalf of the British Admiralty in 1838. After Moresby had taken measurements of most of the atolls and reefs, the archipelago was charted with relative accuracy for the first time.[20]

20th century

On 31 August 1903 the Chagos Archipelago was administratively separated from the Seychelles and attached to Mauritius.[21]

In November 1965, the UK purchased the entire Chagos Archipelago from the then self-governing colony of Mauritius for £3 million to create the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT),[22] with the intent of ultimately closing the plantations to provide the British territory from which the United States would conduct its military activities in the region. On 30 December 1966, the United States and the United Kingdom executed an agreement through an Exchange of Notes which permit the United States Armed Forces to use any island of the BIOT for defence purposes for 50 years, until December 2016,[22] followed by a 20-year optional extension (to 2036) to which both parties must agree by December 2014. As of 2010, only the atoll of Diego Garcia has been transformed into a military facility.

In 1967 the British Government bought the entire assets and real property of the Seychellois Chagos Agalega Company,[23] which owned all the islands of the BIOT,[24] for £660,000[25] and administered them as a government enterprise while awaiting US funding of its proposed facilities, with an interim objective of paying for the administrative expenses of the new territory. The plantations, under their previous private ownership and under government administration, proved consistently unprofitable due to the introduction of new oils and lubricants in the international marketplace and the establishment of vast coconut plantations in the East Indies and the Philippines.

Between 1967 and 1973, the population was forcibly removed from the islands and moved to Mauritius and the Seychelles to make way for a joint United States–United Kingdom military base on Diego Garcia.[26] In March 1971, Seabees, United States naval construction battalions, arrived on Diego Garcia to begin the construction of the Communications Station and an airfield. To satisfy the terms of an agreement between the United Kingdom and the United States for an uninhabited island, the plantation on Diego Garcia was closed in October of that year.[27]

The plantation workers and their families were initially deported to the plantations on Peros Banhos and Salomon atolls in the group; those who requested were transported to the Seychelles or Mauritius. In 1972, the UK closed the remaining plantations (all being now uneconomic) of the Chagos, and deported the Ilois who would have faced economic hardship to the Seychelles or Mauritius. The independent Mauritian government refused to accept these further displaced islanders without payment and in 1973, the United Kingdom agreed and gave them an additional £650,000 as reparation payments to resettle the people.[28] Some in many of their reasonable views were less than ideally rehoused and employed by Mauritius, compared to others. The islands were becoming costly to live in due to industrial moves away from coconut oils and copra fibre markets and the success of larger plantations in the far east.

2000–present

In 2002, Diego Garcia was used twice for US rendition flights.[29]

On 1 April 2010, the British government announced the establishment of the Chagos Marine Protected Area as the world's largest marine reserve. At 640,000 km2, it is larger than France or the U.S. state of California. It doubled the total area of environmental no-take zones worldwide.[30] On 18 March 2015, the Permanent Court of Arbitration unanimously held that the marine protected area (MPA) which the United Kingdom declared around the Chagos Archipelago in April 2010 violates international law. Anerood Jugnauth, Prime Minister of Mauritius, pointed out that it is the first time that the United Kingdom's conduct with regard to the Chagos Archipelago has been considered and condemned by any international court or tribunal.[31][32]

On 20 December 2010 Mauritius initiated proceedings against the United Kingdom under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to challenge the legality of the Chagos Archipelago MPA.

The issue of compensation and repatriation of the former inhabitants of several of the archipelago's atolls, exiled since 1973, continues in litigation and as of 23 August 2010 has been submitted to the European Court of Human Rights by a group of former residents.[33]

Litigation continues as of 2012 regarding the right of return for the displaced islanders and Mauritian sovereignty claims. In addition, advocacy on the Chagossians' behalf continues both in the United States and in Europe. As of 2018, Mauritius has taken the matter to the International Court of Justice for an advisory opinion, against British objections.[34]

In November 2016, the United Kingdom restated it would not permit Chagossians to return to the islands.[35]

In July 2021, the Chagos Refugees Group UK submitted a complaint to the Irish government against domain-name speculators Paul Kane and Ethos Capital subsidiary Afilias, seeking repatriation of the .IO ("Indian Ocean") country-code top-level domain and payment of back royalties from the $7m/year in revenue generated by the domain.[36] While attempts to repatriate top-level domains are not uncommon, this one is notable in that it cites consumer and human rights violations of the OECD's 2011 Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises rather than multistakeholder representation under ICANN policy, and because the .IO domain has enjoyed commercial success, particularly among cryptocurrency companies, with more than 270,000 domains registered.[37][38]

Sovereignty dispute

The Chagos had been administered from imperial offices in Mauritius since the 18th century when the French first named the islands (see map of 18th century, right). All of the islands forming part of the French colonial territory of Isle de France (as Mauritius was often then known) were ceded to the British in 1810 under the Act of Capitulation. In 1965, in planning before Mauritian independence, the UK split the archipelago from the territory of Mauritius to form the British Indian Ocean Territory, looking to provide the US with an uninhabited island base, the country's main creditor after the turmoil of World War II.[4]

United Nations' resolutions on self-determination deprecated the parcelling up of imperial territories before independence, without its endorsement and local support, mindful of the Partition of India which provided the strong governments sought by the separate factions but failed to ensure a relatively peaceful transfer of power in many places. Mauritius has repeatedly stated that the British claim that the Chagos Archipelago is one of its territories thwarted its claim to what would be widely considered part of the Mauritian colony and also breached UN resolutions. The UK has stated that the Chagos will be assigned to Mauritius once the islands are no longer required for defence purposes.[4]

The island nation of Mauritius claims the Chagos Archipelago (which is coterminous with the BIOT), including Diego Garcia. Maldives states that the UK's claim to a 200 nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone around the Chagos Archipelago is invalid as the islands are considered uninhabited.[39] A subsidiary issue is the Mauritian opposition to the 1 April 2010 UK Government's declaration that the BIOT is a Marine Protected Area with fishing and extractive industry (including oil and gas exploration) prohibited.[40]

On 16 November 2016, the UK Foreign Office maintained their ban on repatriation of the islands.[35] In response to this decision, the Prime Minister of Mauritius expressed his country's plan to advance the sovereignty dispute to the International Court of Justice.[41] The British Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson sought Indian assistance for resolving the dispute involving the UK, the US and Mauritius. India has maintained considerable influence in Mauritius through deep cultural and economic ties. India has maintained that the matter of whether or not to proceed with the UN General Assembly move is a decision for the Mauritian government to make.[42]

On 22 June 2017, the UN General Assembly requested the International Court of Justice to give an advisory opinion on the separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius. On 25 February 2019, the International Court of Justice advised that in its opinion:

- “at the time of its detachment from Mauritius” the “Chagos Archipelago was clearly an integral part of that non-self-governing territory";[43]

- the United Kingdom's purported detachment of the Chagos Archipelago “was not based on the free and genuine expression of the will of the people concerned";[43]

- at the time of the purported detachment, “obligations arising under international law and reflected in the resolutions adopted by the General Assembly during the process of decolonization of Mauritius require[d] the United Kingdom, as the administering Power, to respect the territorial integrity of that country, including the Chagos Archipelago";[43]

- the “detachment” was therefore “unlawful” such that “the process of decolonization of Mauritius was not lawfully completed when Mauritius acceded to independence in 1968"[43]

- “the United Kingdom’s continued administration of the Chagos Archipelago constitutes a wrongful act entailing the international responsibility of that State”;[43]

- this “unlawful act” is “of a continuing character” and “the United Kingdom is under an obligation to bring to an end its administration of the Chagos Archipelago as rapidly as possible";[43] and

- “all Member States [of the United Nations] are under an obligation to co-operate with the United Nations in order to complete the decolonization of Mauritius.”[43]

On 23 June 2017, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voted in favour of referring the territorial dispute between Mauritius and the United Kingdom to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in order to clarify the legal status of the Chagos Islands archipelago in the Indian Ocean. The motion was approved by a majority vote with 94 voting for and 15 against.[44][45]

On 22 May 2019, the United Nations General Assembly debated and adopted a resolution that affirmed that the Chagos archipelago “forms an integral part of the territory of Mauritius.” The resolution demanded that the UK "withdraw its colonial administration … unconditionally within a period of no more than six months." 116 states voted in favour of the resolution, 55 abstained and only 5 countries supported the United Kingdom. During the debate, the Mauritian Prime Minister, Sir Anerood Jugnauth, described the expulsion of Chagossians as "akin to a crime against humanity." The resolution's immediate consequence is that the UN and other international organisations are now bound by UN law to support the decolonisation of the Chagos Islands. The United Kingdom continues to assert that it has no doubt about its sovereignty over the archipelago.[46] The Maldives were one of the countries which supported the UK in the General Assembly vote. It stated that, if the Chagos Archipelago became inhabited, the Maldives claim to an extension of its Exclusive Economic Zone would be affected. On 25 February 2019, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) delivered an advisory opinion that placing the Archipelago under British administration in 1965 was not based upon the free expression of the inhabitants and that it thus advised that the United Kingdom should relinquish the archipelago, including the strategic United States military base, for the establishment of which approximately 1,500 inhabitants had been deported. The British government rejected any jurisdiction of the court to deliberate these matters.[47]

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) voted in favor of setting a six-month deadline for the United Kingdom to withdraw from the Chagos Archipelago, which would then be reunified with Mauritius. The motion was approved by a majority vote with 116 voting for and 6 against. Fifty-six states, including France and Germany, abstained.[48][49]

On 28 January 2021, the United Nation's International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) confirmed the International Court of Justice ruling and ordered Britain to hand over the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius.[50] The ITLOS Special Chamber affirmed that: “it is inconceivable that the United Kingdom, whose administration over the Chagos Archipelago constitutes a wrongful act of a continuing character and thus must be brought to an end as rapidly as possible, and yet who has failed to do so, can have any legal interests in permanently disposing of maritime zones around the Chagos Archipelago by delimitation”.[51]

On 14 February 2022, a delegation from Mauritius, including the Mauritian ambassador to the UN, raised the Mauritian flag on the Chagossian atoll of Peros Banhos. The move was done in the context of a scientific survey of Blenheim Reef but was regarded as a formal challenge to British sovereignty over Chagos.[52]

On 3 November 2022, the British Foreign Secretary James Cleverly announced that the UK and Mauritius had decided to begin negotiations on sovereignty over the British Indian Ocean Territory, taking into account the recent international legal proceedings. Both states had agreed to ensure the continued operation of the joint UK/US military base on Diego Garcia.[53][54]

Development

Structures on the islands are located in the joint defence and Naval Support Facility Diego Garcia, although the Plantation house and other structures left behind by the Ilois are still standing, however left abandoned and decaying. Other uninhabited islands, especially in the Salomon Atoll, are common stopping points for long-distance yachtsmen travelling from Southeast Asia to the Red Sea or the coast of Africa, although a permit is required to visit the outer islands.

People and language

The Chagossians

The islanders were known as the Ilois (one French Creole word for "islanders") and they numbered about 1,000. They were of mixed African, South Indian, Portuguese, English, French and Malay descent and lived very simple, spartan lives in their isolated archipelago working in the coconut and sugar plantations, or in the fishing and small textile industries. Few remains of their culture have been left, although their language is still spoken by some of their descendants in Mauritius.

The inhabitants of Chagos were speaking Chagossian Creole, also known as Ilois creole, a French Creole which has not been properly researched from the linguistic point of view.

The island names are a mixture of Dutch, French, English and Ilois Creole.

The tribes that inhabited the islands were forcibly removed by the US and British governments during the late 1960s and early 1970s—effectively turning the islands into a military base. While a number of islanders had petitioned for the return of their former homes and their right to return has been recognized by the UN General Assembly, the International Court of Justice, and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, the US and UK legal systems have refused to adhere to these decisions, leaving the Chagossians in exile.[55]

Other

Diego Garcia is currently the only inhabited island in the Chagos, all of which comprise the British Indian Ocean Territory, usually abbreviated as "BIOT". The UK considers it an Overseas territory of the United Kingdom, and the Government of the BIOT consists of Commissioner appointed by the King on the advice of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. The Commissioner is assisted by an Administrator and small staff, and is based in London and resident in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. This administration is represented in the Territory by the Officer commanding British Forces on Diego Garcia, the "Brit Rep". Laws and regulations are promulgated by the Commissioner and enforced in the BIOT by Brit Rep.

There are no indigenous peoples living on the island, and the UK represents the Territory internationally. A local government as normally envisioned does not exist.[56] Around 1,700 armed services personnel and 1,500 civilian contractors, mostly American, are stationed on Diego Garcia.[57]

As of 2012, the islands have a transitory population of about 3,000 (300 British government personnel and 2,700 United States Army, Navy and Air Force personnel).

The Catholics are pastorally served by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Port-Louis, which includes the BIOT.

Ecology

The Chagos, together with the Maldives and Lakshadweep, forms the Maldives-Lakshadweep-Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests terrestrial ecoregion.[58] The islands and their surrounding waters are a vast oceanic Environment Preservation and Protection Zone (EPPZ) (Fisheries Conservation and Management Zone (FCMZ) of 544,000 square kilometres (210,000 sq mi)), an area twice the size of the UK's land surface.

The deep oceanic waters around the Chagos Islands, out to the 200 nautical mile limit, include an exceptional diversity of undersea geological features (such as 6000 m deep trenches, oceanic ridges, and sea mounts). These areas almost certainly harbour many undiscovered and specially adapted species. Although the deepwater habitats surrounding the islands have not been explored or mapped in any detail, work elsewhere in the world has shown that high physical diversity of the sea floor is closely linked to a high diversity of species.

The biodiversity of the Chagos archipelago and its surrounding waters is one of the main reasons it is so special. As of 2010, 76 species that call Chagos home were listed on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[59]

Coral

The reefs host at least 371 species of coral including the endemic brain coral Ctenella chagius. Historically, the coral cover was dense and healthy even in deep water on the steep outer reef slopes.[60] Thick stands of branching staghorn coral (Acropora sp) previously protected the low-lying islands from wave erosion. Despite the loss of much of the coral in a bleaching event in 1998 the recovery in the Chagos was remarkable and overall coral cover increased year on year to 2014.[61] High water temperatures, however, caused coral bleaching in both 2015 and 2016 which resulted in the death of more than two thirds of corals.[62]

Fish

The reefs are also home to at least 784 species of fish that stay near to the shores of the islands including the endemic Chagos clownfish (Amphiprion chagosensis) and many of the larger wrasse and grouper that have already been lost from over-fishing in other reefs in the region.[63]

As well as the healthy communities of reef fish there are significant populations of pelagic fish such as manta rays (Manta birostris), whale sharks, other sharks, and tuna. Shark numbers have dramatically declined as a result of illegal fishing boats that seek to remove their fins and also as accidental by-catch in the two tuna fisheries that used to operate seasonally in the Chagos.[64]

Birds

Seventeen species of breeding seabird can be found nesting in huge colonies on many of the islands in the archipelago, and 10 of the islands have been designated Important Bird Areas by BirdLife International. This means that Chagos has the most diverse breeding seabird community in this tropical region. Of particular interest are the large colonies of sooty terns (Sterna fuscata), brown and lesser noddies (Anous stolidus and Anous tenuirostris), wedge-tailed shearwaters (Puffinus pacificus) and red-footed boobies (Sula sula). Land bird fauna is poor and consists of introduced species and recent natural colonisers. Red fody has been introduced and is now widespread.

Mammals

Environments in the Chagos Archipelago provide rich biodiversity and support varieties of cetacean species,[65] such as three populations of blue whales[66] and toothed whales (sperm, pilot, orca, pseudo-orca, risso's and other dolphins such as spinners).[67] Dugongs are now locally extinct but once thrived in the archipelago and Sea Cow Island was named after the presence of the species.[68][69] Donkeys left behind when the Ilois were relocated also roam free.

Turtles

The remote islands make perfect undisturbed sites for nests of green (Chelonia mydas) and hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) turtles. The populations of both species in Chagos are of global significance given the critically endangered status of hawksbills and the endangered status of green turtles on the IUCN Red List. Chagos turtles had been heavily exploited for two centuries but they and their habitats are now well protected by the government of the British Indian Ocean Territory and are recovering well.

Crustaceans

The coconut crab (Birgus latro) is the world's largest terrestrial arthropod,[70] reaching more than a metre in leg span and 3.5-4 kilos in weight. As a juvenile it behaves like a hermit crab and uses empty coconut shells as protection, but as an adult this giant crab climbs trees and can crack through a coconut with its massive claws. Despite its wide global distribution it is rare in most of the areas in which it is found. The coconut crabs on Chagos constitute one of the most undisturbed populations in the world.[71][72] An important part of their biology is the long distances their young can travel as larvae. This means the Chagos coconut crabs are a vital source for replenishing other over-exploited populations in the Indian Ocean region.

Insects

113 species of insect have been recorded from the Chagos Islands.

Plants

The Chagos Islands were colonised by plants once there was sufficient soil to support them—probably less than 4,000 years. Seeds and spores arrived on the emerging islands by wind and sea anc from passing seabirds. The native flora of the Chagos Islands is thought to consist of forty-one species of flowering plant and four ferns as well as a wide variety of mosses, liverworts, fungi and cyanobacteria.

Today the status of the Chagos Islands’ native flora depends very much on past exploitation of particular islands. About 280 species of flowering plant and fern have now been recorded on the islands, but this increase reflects the introduction of non-native plants by humans, either accidentally or deliberately. As some of these non-native species have become invasive and pose a threat to the native ecosystems, plans are being developed to control them. On some islands native forests were felled to plant coconut palms for the production of copra oil. Other islands remain unspoiled and support a wide range of habitats, including unique Pisonia forests and large clumps of the gigantic fish poison tree (Barringtonia asiatica). Unspoiled islands provide us with the biological information that we need to re-establish the native plant communities on heavily altered islands. These efforts will ultimately help to improve the biodiversity of the Chagos Islands.

Conservation efforts

Past

Successive UK governments, both Labour and Conservative, have supported environmental conservation of the Chagos. They have committed to treating the whole area as a World Heritage Site. In 2003 the UK government established an Environment (Protection and Preservation) Zone under Article 75 of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea extending 200 nautical miles from the islands. On eastern Diego Garcia, the largest island of the Chagos and the site of a UK–US military facility,[73] Britain has designated the very large lagoon and the eastern arm of the atoll and seaward reefs as a "wetland of international importance" under the Convention on Wetlands of International Importance (the Ramsar Convention).[74]

Present

On 1 April 2010 Britain announced the creation of the Chagos Marine Protected Area, the world's largest continuous marine protected reserve, with an area of 545,000 km2 (210,000 sq mi).[75][76][77]

This followed an effort led by The Chagos Environment Network,[78] a collaboration of nine leading conservation and scientific organisations seeking to protect the rich biodiversity of the Chagos Archipelago and its surrounding waters. The Chagos Environment Network cites several reasons for supporting a protected area:

The UK government opened a three-month public consultation, which ended after 5 March 2010, on conservation management of the Chagos Islands and its surrounding waters.[79]

On 1 April 2010 the British government Cabinet established the Chagos Archipelago as the world's largest marine reserve. At 640,000 km2 it is larger than France or the US state of California. It doubled the total area of environmental no-take zones worldwide.[30] The protection of the marine reserve will be guaranteed for the next five years thanks to the financial support of the Bertarelli Foundation.[80] The setting up of the Marine Reserve would appear to be an attempt to prevent any repatriation by the inhabitants evicted in the 1960s and 1970s. Leaked US cables have shown the FCO suggesting to its US counterparts that setting up a protected no-take zone would make it "difficult, if not impossible" for the islanders to return. The reserve was then created in 2010.[81]

Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling

On 18 March 2015 the Permanent Court of Arbitration unanimously held that the marine protected area (MPA) that the UK had declared around the Chagos Archipelago in April 2010 violated international law. Anerood Jugnauth, Prime Minister of Mauritius, pointed out that it was the first time that the UK's conduct with regard to the Chagos Archipelago had been considered and condemned by any international court or tribunal. He qualified the ruling as an important milestone in the relentless struggle, at the political, diplomatic and other levels, of successive Governments over the years for the effective exercise by Mauritius of its sovereignty over the Chagos Archipelago. The tribunal considered in detail the undertakings given by the United Kingdom to the Mauritian Ministers at the Lancaster House talks in September 1965. The UK had argued that those undertakings were not binding and had no status in international law. The Tribunal firmly rejected that argument, holding that the undertakings became a binding international agreement upon the independence of Mauritius and had bound the UK ever since. It found that the UK's commitments towards Mauritius in relation to fishing rights and oil and mineral rights in the Chagos Archipelago were legally binding. The Tribunal also found that the United Kingdom's undertaking to return the Chagos Archipelago to Mauritius when no longer needed for defence purposes was legally binding. This establishes that, in international law, Mauritius has real, firm and binding rights over the Chagos Archipelago and that the United Kingdom must respect those rights. The Tribunal went on to hold that the United Kingdom had not respected Mauritius’ binding legal rights over the Chagos Archipelago. It considered the events from February 2009 to April 2010, during which time the MPA proposal came into being and was then imposed on Mauritius.[31][32]

WikiLeaks cablegate disclosure

According to WikiLeaks cablegate documents,[82] the UK and US both have interests to safeguard and see strategic value. The summary paragraph of the diplomatic cable referred to follows:

"HMG would like to establish a marine park or reserve providing comprehensive environmental protection to the reefs and waters of the British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), a senior Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) official informed Polcouns on May 12. The official insisted that the establishment of a marine park—the world's largest—would in no way impinge on USG use of the BIOT, including Diego Garcia, for military purposes. He agreed that the UK and U.S. should carefully negotiate the details of the marine reserve to assure that U.S. interests were safeguarded and the strategic value of BIOT was upheld. He said that the BIOT's former inhabitants would find it difficult, if not impossible, to pursue their claim for resettlement on the islands if the entire Chagos Archipelago were a marine reserve."[83]

See also

- List of islands in Chagos Archipelago

- Chagos Archipelago sovereignty dispute

- Expulsion of the Chagossians

- Great Chagos Bank

- Chagos Marine Protected Area

- Depopulation of Diego Garcia

- List of island countries and territories in the Indian Ocean

- British Indian Ocean Territory

- Indian Ocean

- Scattered Islands

References

- "British Indian Ocean Territory". CIA.gov. Retrieved 4 November 2018.

- "Track of the Calcutta East Indiaman, over the Bassas de Chagas in the Indian Ocean". Catalogue.nla.gov.au. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- World Wildlife Fund, ed. (2001). "Maldives-Lakshadweep-Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 8 March 2010. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Time for UK to Leave Chagos Archipelago". Real clear world. 6 April 2012. Retrieved 12 July 2012.

- Nichols, Michelle (22 June 2017). "U.N. asks international court to advise on Chagos; Britain opposed". Reuters. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- "Legal Consequences of the Separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965". International Court of Justice.

- "Sega tambour Chagos - intangible heritage - Culture Sector - UNESCO". Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "UN court rules UK has no sovereignty over Chagos islands". BBC News. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- Siddique, Haroon (16 May 2021). "UN favours Mauritian control of Chagos Islands by rejecting UK stamps". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- "UN bans British stamps in Chagos island". The Hindu. 26 August 2021 – via www.thehindu.com.

- "House of Commons Hansard Written Answers for 21 Jun 2004 (pt 13)". Publications.parliament.uk. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- Romero-Frias, Xavier (2012). Folk tales of the Maldives, NIAS Press, ISBN 978-87-7694-104-8, ISBN 978-87-7694-105-5.

- Romero-Frias, Xavier, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom. Barcelona, 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5. Chapter 1 "A Seafaring Nation", p. 19.

- Huddart, Joseph, et al. The oriental navigator, or, New directions for sailing to and from the East Indies, ISBN 978-0-699-11218-5.

- Purdy, John, Memoir, descriptive explanatory, accompany new chart Ethiopic or southern Atlantic Ocean, western coasts South-America, Cape Horn Panama, ISBN 1-141-62555-5.

- Boxer, C. R., The Portuguese Seaborne Empire, 1415-1825, Knopf, 1969, ISBN 978-0-09-097940-0.

- Bernardo Gomes de Brito. História trágico-marítima. Em que se escrevem chronologicamente os Naufragios que tiverao as Naos de Portugal, depois que se poz em exercicio a Navegaçao da India. Lisboa 1735

- "US-UK-Diego Garcia (1770-2004)". History Commons. Archived from the original on 30 December 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- Christian Nauvel (2007). "A Return from Exile in Sight? The Chagossians and Their Struggle" (PDF). Northwestern Journal of International Human Rights. 5 (1): 6. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- British Hydrographic Services. Admiralty Charts. Maps in the Chagos Archipelago.

- A New Comprehensive History of Mauritius Vol 1. Sydney Selvon. pp. 398–. ISBN 978-99949-34-94-2.

- Colonialism: An International Social, Cultural, and Political Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. 2003. pp. 375–. ISBN 978-1-57607-335-3.

- Evers, Sandra; Marry Kooy (23 May 2011). Eviction from the Chagos Islands: Displacement and Struggle for Identity Against Two World Powers. BRILL. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-90-04-20260-3.

- Stephen Allen (16 October 2014). The Chagos Islanders and International Law. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 277–. ISBN 978-1-78225-474-4.

- David Vine (3 January 2011). Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia. Princeton University Press. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-1-4008-3850-9.

- "Exiles lose appeal over benefits". BBC Online. 2 November 2007.

- Will Kaufman; Macpherson, Heidi Slettedahl (2005). Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History : a Multidisciplinary Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 319–. ISBN 978-1-85109-431-8.

- Laura Jeffery (19 July 2013). Chagos Islanders in Mauritius and the UK: Forced displacement and onward migration. Manchester University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-84779-789-6.

- "In full: Miliband rendition statement". BBC. 21 February 2008. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- North Sea Marine Cluster. "Managing Marine Protected Areas" (PDF). NSMC. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 5 February 2013.

- "Mauritius: MPA Around Chagos Archipelago Violates International Law - This Is a Historic Ruling for Mauritius, Says PM". Allafrica.com/. Retrieved 23 March 2015.

- "MPA around Chagos Archipelago violates international law – This is a Historic ruling for Mauritius, says PM". Government Portal of Mauritius. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Philp, Catherine (6 March 2010). "Chagossians fight for a home in paradise". The Sunday Times. Archived from the original on 24 September 2011. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Harding, Andrew (27 August 2018). "Chagos Islands dispute: UK 'threatened' Mauritius". BBC.

- Bowcott, Owen (16 November 2016). "Chagos islanders cannot return home, UK Foreign Office confirms". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Levy, Jonathan. "COMPLAINT FILED AGAINST Afilias Ltd. (Ireland) including its subsidiaries 101domain GRS Limited (Ireland), Internet Computer Bureau Limited (England & British Indian Ocean Territory) In Respect of OECD Guidelines Violations in Operation of ccTLD .io BEFORE THE IRELAND OECD NATIONAL CONTACT POINT" (PDF). Chagos Refugees Group UK. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- Murphy, Kevin (9 November 2018). "Afilias bought .io for $70 million". Domain Incite. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- Goldstein, David (30 July 2021). "Chagos Islanders Lodge Complaint With OECD to Get Their .IO Back". Goldstein Report. Retrieved 2 August 2021.

- "Maldives defends UN vote on Chagos Islands dispute". Maldives Independent. 23 May 2019.

- "Mauritius to reiterate its conditions for renewed talks with UK on Chagos". Afrique Avenir. 14 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 December 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- Bowcott, Owen (17 November 2016). "Mauritius threatens to take Chagos Islands row to UN court". The Guardian.

- Ram, Vidya (19 January 2017). "U.K. seeks Indian help in resolving Chagos Archipelago dispute". The Hindu. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- International Court of Justice (25 February 2019). "Advisory Opinion on the Legal Consequences of the Separate of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965" (PDF). International Court of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2020.

- Sengupta, Somini (22 June 2017). "U.N. Asks International Court to Weigh In on Britain-Mauritius Dispute". The New York Times.

- "Chagos legal status sent to international court by UN". BBC News. 22 June 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2017.

- Sands, Philippe (24 May 2019). "At last, the Chagossians have a real chance of going back home". The Guardian.

Britain's behaviour towards its former colony has been shameful. The UN resolution changes everything

- Bowcott, Owen (25 February 2019). "UN court rejects UK's claim of sovereignty over Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 February 2019.

- "Chagos Islands dispute: UN backs end to UK control". BBC News. 22 May 2019.

- Bowcott, Owen; Julian Borger (22 May 2019). "UK suffers crushing defeat in UN vote on Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- "UN court rules UK has no sovereignty over Chagos islands". BBC News. 28 January 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2021.

- International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (28 January 2021). "Dispute Concerning Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary Between Mauritius and Maldives in the Indian Ocean (Mauritius/Maldives)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2021.

- Bowcott, Owen; Bruno Rinvolucri (14 February 2022). "Mauritius formally challenges Britain's ownership of Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 February 2022.

- Wintour, Patrick (3 November 2022). "UK agrees to negotiate with Mauritius over handover of Chagos Islands". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- Cleverly, James (3 November 2022). "Chagos Archipelago". Hansard. UK Parliament. HCWS354. Retrieved 3 November 2022.

- "Chagos islanders cannot return home, says Supreme Court". Bbc.com. 29 June 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "Diego Garcia 'Camp Justice' 7º20'S 72º25'E". Global Security.org. Retrieved 17 July 2014.

- "Maldives-Lakshadweep-Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "A Marine Protected Area (MPA) in Chagos" (PDF). IUCN. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- Andradi-Brown, Dominic A.; Dinesen, Zena; Head, Catherine E. I.; Tickler, David M.; Rowlands, Gwilym; Rogers, Alex D. (2019), Loya, Yossi; Puglise, Kimberly A.; Bridge, Tom C.L. (eds.), "The Chagos Archipelago", Mesophotic Coral Ecosystems, Coral Reefs of the World, Springer International Publishing, pp. 215–229, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-92735-0_12, ISBN 9783319927350, S2CID 181769548

- Lange, Ines D.; Perry, Chris T. (1 August 2019). "Bleaching impacts on carbonate production in the Chagos Archipelago: influence of functional coral groups on carbonate budget trajectories". Coral Reefs. 38 (4): 619–624. Bibcode:2019CorRe..38..619L. doi:10.1007/s00338-019-01784-x. ISSN 1432-0975.

- Head, Catherine E. I.; Bayley, Daniel T. I.; Rowlands, Gwilym; Roche, Ronan C.; Tickler, David M.; Rogers, Alex D.; Koldewey, Heather; Turner, John R.; Andradi-Brown, Dominic A. (12 July 2019). "Coral bleaching impacts from back-to-back 2015–2016 thermal anomalies in the remote central Indian Ocean". Coral Reefs. 38 (4): 605–618. Bibcode:2019CorRe..38..605H. doi:10.1007/s00338-019-01821-9. ISSN 1432-0975.

- SHEPPARD, C. R. C.; ATEWEBERHAN, M.; BOWEN, B. W.; CARR, P.; CHEN, C. A.; CLUBBE, C.; CRAIG, M. T.; EBINGHAUS, R.; EBLE, J.; FITZSIMMONS, N.; GAITHER, M. R. (March 2012). "Reefs and islands of the Chagos Archipelago, Indian Ocean: why it is the world's largest no-take marine protected area". Aquatic Conservation: Marine and Freshwater Ecosystems. 22 (2): 232–261. doi:10.1002/aqc.1248. ISSN 1052-7613. PMC 4260629. PMID 25505830.

- Márquez, Melissa Cristina (26 March 2019). "Sharks Crack The Case: Uncovering Illegal Activities In Paradise". Forbes. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 March 2016. Retrieved 2 March 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Dunne R. P., Polunin N. V., Sand P. H., Johnson M. L., 2014. The Creation of the Chagos Marine Protected Area: A Fisheries Perspective. Advances in Marine Biology (69). pp. 79–127. ResearchGate.

- "Concerns about the Chagos Archipelago MPA Proposal". Us.whales.org. Archived from the original on 5 July 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "Conservation and Management in British Indian Ocean Territory (Chagos Archipelago)" (PDF). Chagos-trust.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- "Dugong dugon, dugong". Sealifebase.org. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- Charles Sheppard (14 March 2013). Coral Reefs of the United Kingdom Overseas Territories. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 278–. ISBN 978-94-007-5965-7.

- "A Diversity of Decapods". Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation. 10 April 2015. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- IUCN Commission on National Parks and Protected Areas (1991). Protected Areas of the World: Afrotropical. IUCN. pp. 341–. ISBN 978-2-8317-0092-2.

- Pike, John. "Diego Garcia 'Camp Justice'". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Wetland and marine protected areas on the world heritage list". Retrieved 30 August 2016.

- Eilperin, Juliet (2 April 2010), "Britain protects Chagos Islands, creating world's largest marine reserve", The Washington Post, Green, retrieved 4 April 2010

- Rincon, Paul (1 April 2010), "UK sets up Chagos Islands marine reserve", BBC News, retrieved 7 April 2010

- "New protection for marine life", Foreign & Commonwealth Office, 1 April 2010, archived from the original on 12 December 2012, retrieved 7 April 2010

- "Welcome to the Chagos Conservation Trust | Chagos Conservation Trust". Protectchagos.org. Archived from the original on 19 January 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- "Consultation on Whether to Establish a Marine Protected Area in the British Indian Ocean Territory". Archived from the original on 6 February 2010. Retrieved 6 February 2010.

- PA (12 September 2010). "Billionaire saves marine reserve plans". London: Independent.co.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2012.

- Evans, Rob; Richard Norton-Taylor (2 December 2010). "WikiLeaks: Foreign Office accused of misleading public over Diego Garcia | Politics". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 20 October 2013.

- "Hmg Floats Proposal For Marine Reserve Covering". Embassy London. WikiLeaks. 15 May 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2010.

- Cable from AMEMBASSY LONDON; DTG 150700ZMAY09; SUBJECT: Political Counselor Richard Mills for reasons 1.4 b and d.

Further reading

- Sands, Philippe (2022), The Last Colony: A Tale of Exile, Justice and Britain's Colonial Legacy, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, ISBN 978-1-4746-1812-0

- Wenban-Smith, N. and Carter, M. (2016) Chagos: A History, Exploration, Exploitation, Expulsion, Chagos Conservation Trust: London. ISBN 978-0-9954596-0-1

- Pilger, John (2006). Freedom Next Time. Bantam Press. ISBN 0-593-05552-7. Chapter 1: Stealing a Nation, pp. 19–60

- Padma Rao, Der Edikt der Königin, in: Der Spiegel, 5 December 2005, pp. 152–4.

- Xavier Romero-Frias, The Maldive Islanders, A Study of the Popular Culture of an Ancient Ocean Kingdom. Barcelona 1999, ISBN 84-7254-801-5

- David Vine, Island of Shame: The Secret History of the US Military Base on Diego Garcia. Princeton University Press 2009, ISBN 978-0-691-13869-5

Novels

- Shenaz Patel, Le silence des Chagos, Éditions de l'Olivier, 2005, ISBN 9782879294544

- Caroline Laurent, Rivage de la colère, Les Escales, 2020, ISBN 9782266311915