French-based creole languages

A French creole, or French-based creole language, is a creole for which French is the lexifier. Most often this lexifier is not modern French but rather a 17th- or 18th-century koiné of French from Paris, the French Atlantic harbors, and the nascent French colonies. This article also contains information on French pidgin languages, contact languages that lack native speakers.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| French language |

|---|

| History |

| Grammar |

| Orthography |

| Phonology |

|

These contact languages are not to be confused with non-creole varieties of French outside of Europe that date to colonial times, such as Acadian, Louisiana, New England or Quebec French.

There are over 15.5 million speakers of some form of French-based creole languages. Haitian Creole is debatably the most spoken creole language in the world, with over 12 million speakers.

History

Throughout the 17th century, French Creoles became established as a unique ethnicity originating from the mix of French, Indian, and African cultures. These French Creoles held a distinct ethno-cultural identity, a shared antique language, Creole French, and their civilization owed its existence to the overseas expansion of the French Empire.[1]

In the eighteenth century, Creole French was the first and native language of many different peoples including those of European origin in the West Indies.[2] French-based creole languages today are spoken natively by millions of people worldwide, primarily in the Americas and on archipelagos throughout the Indian Ocean.

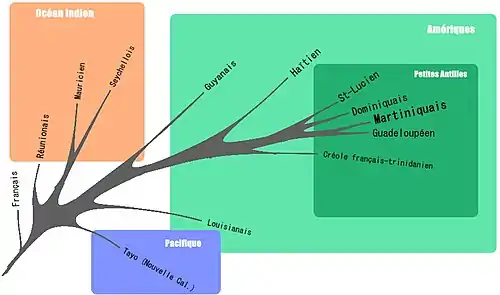

Classification

Americas

- Varieties with progressive aspect marker ape, derived from après[3]

- Haitian Creole (Kreyòl ayisyen, locally called Creole) is a language spoken primarily in Haiti: the largest French-derived language in the world, with an estimated total of 12 million fluent speakers. It is also the most-spoken creole language in the world and is based largely on 17th-century French with influences from Portuguese, Spanish, English, Taíno, and West African languages.[4] It is an official language in Haiti.

- Louisiana Creole (Kréyol la Lwizyàn, locally called Kourí-Viní and Creole), the Louisiana creole language.

- Varieties with progressive aspect marker ka[5]

- Antillean Creole, spoken in the Lesser Antilles, particularly in Martinique, Guadeloupe, Dominica, and Saint Lucia. Although all of the creoles spoken on these islands are considered to be the same language, there are noticeable differences between the dialects of each island. Notably, the Creole spoken in the Eastern (windward) part of the island Saint-Barthélemy is spoken exclusively by a white population of European descent, imported into the island from Saint Kitts in 1648.

- French Guianese Creole is a language spoken in French Guiana, and to a lesser degree in Suriname and Guyana. It is closely related to Antillean Creole, but there are some noteworthy differences between the two.

- Karipúna French Creole, spoken in Brazil, mostly in the state of Amapá. It was developed by Amerindians, with possible influences from immigrants from neighboring French Guiana and French territories of the Caribbean and with a recent lexical adstratum from Portuguese.

- Lanc-Patuá, spoken more widely in the state of Amapá, is a variety of the former, possibly the same language.

Indian Ocean

- Varieties with progressive aspect marker ape[3] – subsumed under a common classification as Bourbonnais Creoles

- Mauritian Creole, spoken in Mauritius (locally Kreol)

- Agalega creole, spoken in Agaléga Islands

- Chagossian creole, spoken by the former population of the Chagos Archipelago

- Réunion Creole, spoken in Réunion

- Rodriguan creole, spoken on the island of Rodrigues

- Seychellois Creole, spoken everywhere in the Seychelles and locally known as Kreol seselwa. It is the national language and shares official status with English and French.

Pacific

- Tayo, spoken in New Caledonia

See also

- Michif

- Chiac

- Camfranglais, a macaronic language of Cameroon

Notes

- Carl A. Brasseaux, Glenn R. Conrad (1992). The Road to Louisiana: The Saint-Domingue Refugees, 1792-1809. New Orleans: Center for Louisiana Studies, University of Southwestern Louisiana. pp. 4, 5, 6, 8, 11, 15, 21, 22, 33, 38, 108, 109, 110, 143, 173, 174, 235, 241, 242, 243, 252, 253, 254, 268.

- Francis Byrne; John A. Holm (1993). Atlantic Meets Pacific: A Global View of Pidginization and Creolization ; Elected Papers from the Society for Pidgin and Creole Linguistics. United States of America: John Benjamins Publishing. p. 394.

- with variants ap and pe, from the koiné French progressive aspect marker àprè <après> Henri Wittmann. 1995, "Grammaire comparée des variétés coloniales du français populaire de Paris du 17e siècle et origines du français québécois", in Fournier, Robert, & Wittmann, Henri, Le français des Amériques, Trois-Rivières: Presses universitaires de Trois-Rivières, pp. 281–334.

- Bonenfant, Jacques L. (2011). "History of Haitian-Creole: From Pidgin to Lingua Franca and English Influence on the Language" (PDF). Review of Higher Education and Self-Learning. 3 (11). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 March 2015.

- from the Karipúna substratum (Henri Wittmann. 1995, "Grammaire comparée des variétés coloniales du français populaire de Paris du 17e siècle et origines du français québécois", in Fournier, Robert & Wittmann, Henri, Le français des Amériques, Trois-Rivières: Presses universitaires de Trois-Rivières, pp. 281–334.