Chaldean dynasty

The Chaldean dynasty, also known as the Neo-Babylonian dynasty[2][lower-alpha 2] and enumerated as Dynasty X of Babylon,[2][lower-alpha 3] was the ruling dynasty of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, ruling as kings of Babylon from the ascent of Nabopolassar in 626 BC to the fall of Babylon in 539 BC. The dynasty, as connected to Nabopolassar through descent, was deposed in 560 BC by the Aramean official Neriglissar (r. 560–556 BC), though he was connected to the Chaldean kings through marriage and his son and successor, Labashi-Marduk (r. 556 BC), might have reintroduced the bloodline to the throne. The final Neo-Babylonian king, Nabonidus (r. 556–539 BC), was genealogically unconnected to the previous kings, but might, like Neriglissar, also have been connected to the dynasty through marriage.

| Chaldean dynasty | |

|---|---|

| Royal family | |

A lion, as depicted in reliefs on the Ishtar Gate, of Babylon's Procession Street[lower-alpha 1] | |

| Country | Babylonia |

| Founded | 626 BC |

| Founder | Nabopolassar |

| Final ruler | Amēl-Marduk or Labashi-Marduk (bloodline) Nabonidus (through marriage?) |

| Titles | King of Babylon King of Sumer and Akkad King of the Universe |

| Traditions | Ancient Mesopotamian religion |

| Deposition | 560 or 556 BC (bloodline) 539 BC (through marriage?) |

| Periods and dynasties of Babylon |

|---|

|

All years are BC |

|

See also: List of kings by Period and Dynasty |

History

The term "Chaldean dynasty", and the corresponding "Chaldean Empire", an alternate historiographical name for the Neo-Babylonian Empire, derives from the assumption that the dynasty's founder, Nabopolassar, was of Chaldean origin.[7] Though contemporary sources suggest an origin in southern Mesopotamia, such as the Uruk prophecy text describing Nabopolassar as a "king of the sea" (i.e. southernmost Babylonia) and a letter from the Assyrian king Sinsharishkun describing him as "of the lower sea" (also southernmost Babylonia), there is no source that ascribes him a specific ethnic origin.[8] Since the Chaldeans lived in southernmost Mesopotamia, many historians have identified Nabopolassar as Chaldean,[7][9][10] but others have referred to him as Assyrian[11] or Babylonian.[12]

The issue is compounded by the fact that Nabopolassar never wrote of his ancestry, going as far as identifying himself as a "son of a nobody". This is almost certainly a lie since an actual son of a nobody, i.e. an obscure figure, would have been unable to gather enough influence to become king of Babylon.[13] There is several pieces of evidence that links Nabopolassar and his dynasty to the city of Uruk (which was located south of Babylon), prominently that several of Nabopolassar's descendants lived in the city[14] and that his son and successor, Nebuchadnezzar II, worked as a priest there before becoming king. In 2007, the Assyriologist Michael Jursa identified Nabopolassar as the son of Nebuchadnezzar (or Kudurru), a governor of Uruk who had been appointed by the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. This Nebuchadnezzar belonged to a prominent political family in Uruk, which would explain how Nabopolassar could rise to power, and the names of his relatives correspond to names later given to Nabopolassar's descendants, possibly indicating a familial relationship through patronymics. As Nabopolassar spent his reign fighting the Assyrians, calling himself a "son of a nobody" instead of associating himself with a pro-Assyrian governor might have been politically advantageous.[15]

Nabopolassar's descendants ruled Babylonia until his grandson, Amel-Marduk, was deposed by the general and official Neriglissar in 560 BC. Neriglissar was powerful and influential prior to becoming king, but was not related to the dynasty by blood, instead likely being of Aramean origin, probably of the Puqudu clan.[16][7] He was not completely unconnected to the Chaldean dynasty, however, having secured his claim to the throne through marriage to one of Nebuchadnezzar II's daughters, possibly Kaššaya.[17][18][19] Neriglissar was succeeded by his son, Labashi-Marduk, who was deposed shortly thereafter. Why Labashi-Marduk was deposed is not known, but it is possible that he was the son of Neriglissar and a wife other than Nebuchadnezzar II's daughter, and thus completely unconnected to the Chaldean dynasty.[20]

The leader of the coup to depose Labashi-Marduk was likely the courtier Belshazzar, who in Labashi-Marduk's place proclaimed Nabonidus, Belshazzar's father, as king.[21] The sources suggest that while he was part of the conspiracy, Nabonidus had not intended, nor expected, to become king himself and he was hesitant to accept the nomination.[22] Nabonidus's rise to the throne put Belshazzar first in the line of succession (it would not have been suitable for him to have become king himself while his father was still alive) and also made him one of the wealthiest men in Babylonia as he inherited Labashi-Marduk's family's estates.[21] It is probable that Nabonidus, like Neriglissar, was also married to a daughter of Nebuchadnezzar II and that this was the method in which he had secured a claim to the throne. This would also explain later traditions that Belshazzar was a descendant of Nebuchadnezzar II.[23] Nabonidus appears to have been a devotee of the god Sîn, though the extent to which he might have attempted to elevate Sîn over Babylon's national deity Marduk is disputed. Subsequent Babylonians appear to have remembered Nabonidus as unorthodox and misguided, though not insane or necessarily a bad ruler.[24] Belshazzar never became king and Babylon ultimately fell under Nabonidus's leadership, as Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid Empire invaded Babylonia in 539 BC and put an end to the Neo-Babylonian Empire. The fates of Nabonidus and Belshazzar are not known. Nabonidus may have been allowed to live and retire but it is typically assumed that Belshazzar was killed.[25]

Family tree of the Chaldean dynasty

Broadly follows Wiseman (1983).[26] The reconstruction of Nabopolassar's ancestry follows Jursa (2007),[27] Neriglissar's ancestry follows Wiseman (1991)[18] and the children of Nebuchadnezzar II follow Beaulieu (1998)[28] and Wiseman (1983).[29] It is not clear whether Labashi-Marduk and Gigitum were Neriglissar's children by Kashshaya, or by another wife unrelated to the ruling dynasty.[20] It is also not certain that Nabonidus actually married one of Nebuchadnezzar's daughters, which puts some uncertainty on the assumption that Belshazzar and his siblings were descendants of Nebuchadnezzar.[30] The birth order of any of the children, besides Nebuchadnezzar being Nabopolassar's oldest son and Nabu-shum-lishir being Nabopolassar's second son, is uncertain.[31]

| Nabonassar | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Puqudu clan (Arameans) | Nebuchadnezzar ('Kudurru') | Nabû-ušabši | Bēl-uballiṭ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nabû-epir-la'a | Median dynasty | Nabopolassar r. 626 – 605 BC | Nabû-šumu-ukīn | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bel-šum-iškun | Amytis | Nebuchadnezzar II r. 605 – 562 BC | Nabû-šum-līšir | Nabû-zer-ušabši | Adad-gûppîʾ | Nabû-balātsu-iqbi | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Neriglissar r. 560 – 556 BC | Kaššaya | Innin-etirat | Ba'u-asitu | Marduk-nadin-ahi | Eanna-šarra-uṣur | Amel-Marduk r. 562 – 560 BC | Marduk-šum-uṣur | Marduk-nadin-šumi | Mušezib-Marduk | A daughter (?) (Nitocris?) | Nabonidus r. 556 – 539 BC | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Labaši-Marduk r. 556 BC | Gigitum | Nabû-šuma-ukin | Indû | Belshazzar | Ennigaldi-Nanna | Ina-Esagila-remat | Akkabuʾunma | Others [lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Descendants (?)[lower-alpha 5] | Descendants (?)[lower-alpha 6] | Descendants [lower-alpha 4] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

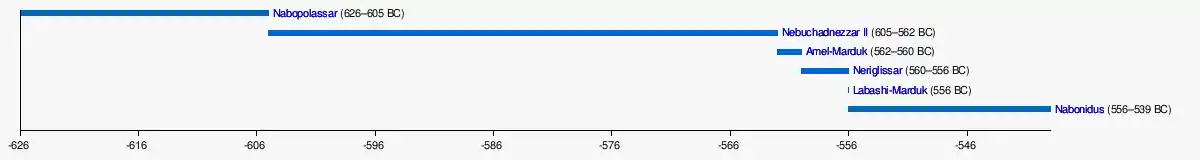

Timeline of Neo-Babylonian rulers

Notes

- The striding lion, with its tail curved upwards, was prominently used as a royal symbol during the Neo-Babylonian Empire, appearing on a large number of bricks, seals and contracts. Such lions were also, together with other animals, prominently used in the reliefs of Babylon's Procession Street. The symbol was also used to denote royal property, with objects belonging to the king being marked with a striding lion, together with a short inscription naming the king.[1]

- The native name of this dynasty is not preserved in any sources and thus several alternate names have been used by historians.[3] In addition to the 'Chaldean dynasty' and 'Neo-Babylonian dynasty', other names historically used by some scholars include 'Nebuchadnezzar's dynasty', the 'Bit-Yakin dynasty' and the 'Third Sealand dynasty'.[4] The Bit-Yakin were a powerful Chaldean tribe in southern Babylonia. Though there is no evidence that connects them to the Chaldean dynasty, the tribe had supplied Babylonian kings previously, such as Marduk-apla-iddina II (r. 722–710 BC and 703 BC).[5]

- The numerical designation XI, rather than X, was often used in older scholarship, when the king Nabu-mukin-apli (r. c. 978–943 BC) was mistakenly ascribed to a dynasty of his own, rather than to the dynasty of E (Dynasty VIII).[6]

- The two later Babylonian rebels Nebuchadnezzar III and Nebuchadnezzar IV both claimed to be sons of Nabonidus, but this was not true for either rebel. Nebuchadnezzar III was actually the son of a man called Mukīn-zēri and Nebuchadnezzar IV was of Urartian (Armenian) origin.[32] Regardless of the illegitimacy of these rebels, it is known that Nabonidus had great-grandchildren, though their names and precise lineages are not known.[33] Records at Sippar may indicate the existence of at least one more daughter of Nabonidus, though her name is not known.[34]

- Nabû-šuma-ukin was the son of a man named Širikti-Marduk and belonged to the prominent Arkâ-ilī-damqā family in Borsippa, serving as the high priest of that city's main temple, the Ezida.[35] His family's presence in Babylonia is recorded since the reign of the 8th-century BC king Nabu-shuma-ishkun. The Arkâ-ilī-damqā family is last attested in Borsippa and Babylon in the reign of Darius the Great (r. 522–486 BC).[36]

- Later Jewish tradition ascribes Belshazzar a daughter called Vashti, who in the Book of Esther is described as the first wife of the king Ahasuerus. Her existence is not historically verified.[37]

References

- Lambert & Zilberg 2017, p. 144.

- Beaulieu 2018, p. 12.

- Beaulieu 2018, p. 13.

- Wiseman 1991, p. 229.

- Radner 2012.

- Bayles Paton 1901, p. 16.

- Beaulieu 2016, p. 4.

- Jursa 2007, pp. 131–132.

- Johnston 1901, p. 20.

- Bedford 2016, p. 56.

- The British Museum 1908, p. 10.

- Melville 2011, p. 16.

- Jursa 2007, pp. 130–131.

- Beaulieu 1998, p. 198.

- Jursa 2007, pp. 127–135.

- Beaulieu 1998, p. 199.

- Beaulieu 1998, p. 200.

- Wiseman 1991, p. 241.

- Lendering 2006.

- Gruenthaner 1949, p. 409.

- Beaulieu 1989, p. 98.

- Beaulieu 1989, p. 89.

- Wiseman 1991, p. 244.

- Beaulieu 2007, p. 139.

- Beaulieu 1989, p. 231.

- Wiseman 1983, p. 12.

- Jursa 2007, p. 133.

- Beaulieu 1998, pp. 174–175, 199–200.

- Wiseman 1983, pp. 10–12.

- Chavalas 2000, p. 164.

- Wiseman 1983, pp. 7–12.

- Nielsen 2015, pp. 55–57.

- Beaulieu 1989, p. 77.

- Beaulieu 1989, p. 137.

- Frame 1984, p. 70.

- Frame 1984, p. 73.

- Grassi 2008, p. 200.

Bibliography

- Bayles Paton, Lewis (1901). "Recent Investigations in Ancient Oriental Chronology". The Biblical World. 18 (1): 13–30. doi:10.1086/472845. JSTOR 3137273. S2CID 144421909.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1989). Reign of Nabonidus, King of Babylon (556-539 BC). Yale University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt2250wnt. ISBN 9780300043143. JSTOR j.ctt2250wnt. OCLC 20391775.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (1998). "Ba'u-asītu and Kaššaya, Daughters of Nebuchadnezzar II". Orientalia. 67 (2): 173–201. JSTOR 43076387.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2007). "Nabonidus the Mad King: A Reconsideration of His Steles from Harran and Babylon". In Heinz, Marlies; Feldman, Marian H. (eds.). Representations of Political Power: Case Histories from Times of Change and Dissolving Order in the Ancient Near East. Eisenbrauns. ISBN 978-1575061351.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2016). "Neo‐Babylonian (Chaldean) Empire". The Encyclopedia of Empire. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. pp. 1–5. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe220. ISBN 978-1118455074.

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2018). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75. Pondicherry: Wiley. ISBN 978-1405188999.

- Bedford, Peter R. (2016). "Assyria's Demise as Recompense: A Note on Narratives of Resistance in Babylonia and Judah". In Collins, John J.; Manning, J. G. (eds.). Revolt and Resistance in the Ancient Classical World and the Near East: In the Crucible of Empire. Brill Publishers. ISBN 978-9004330184.

- Chavalas, Mark W. (2000). "Belshazzar". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN 9789053565032.

- Dalley, Stephanie (2003). "The Hanging Gardens of Babylon?". Herodotus and His World: Essays from a Conference in Memory of George Forrest. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199253746.

- Frame, G. (1984). "The "First Families" of Borsippa during the Early Neo-Babylonian Period". Journal of Cuneiform Studies. 36 (1): 67–80. doi:10.2307/1360012. JSTOR 1360012. S2CID 163534822.

- Grassi, Giulia F. (2008). "Belshazzar's Feast and Feats: the Last prince of Babylon in Ancient Eastern and Western Sources". KASKAL. 5 (5): 187–210. doi:10.1400/118348.

- Gruenthaner, Michael J. (1949). "The Last King of Babylon". The Catholic Biblical Quarterly. 11 (4): 406–427. JSTOR 43720153.

- Jursa, Michael (2007). "Die Söhne Kudurrus und die Herkunft der neubabylonischen Dynastie" [The Sons of Kudurru and the Origins of the New Babylonian Dynasty]. Revue d'assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale (in German). 101 (1): 125–136. doi:10.3917/assy.101.0125.

- Johnston, Christopher (1901). "The Fall of Nineveh". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 22: 20–22. doi:10.2307/592409. JSTOR 592409.

- Lambert, Wilfred G.; Zilberg, Peter (2017). "A Silver Bowl with an Inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. 111: 141–146. doi:10.3917/assy.111.0141. JSTOR 44646411.

- Melville, Sarah C. (2011). "The Last Campaign: the Assyrian Way of War and the Collapse of the Empire". In Lee, Wayne E. (ed.). Warfare and Culture in World History. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0814752784.

- Nielsen, John P. (2015). ""I Overwhelmed the King of Elam": Remembering Nebuchadnezzar I in Persian Babylonia". In Silverman, Jason M.; Waerzeggers, Caroline (eds.). Political Memory in and After the Persian Empire. SBL Press. ISBN 978-0884140894.

- The British Museum (1908). A Guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian Antiquities. London: British Museum. OCLC 70331064.

- Wiseman, Donald J. (1983). Nebuchadrezzar and Babylon: The Schweich Letters. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197261002.

- Wiseman, Donald J. (2003) [1991]. "Babylonia 605–539 B.C.". In Boardman, John; Edwards, I. E. S.; Hammond, N. G. L.; Sollberger, E.; Walker, C. B. F. (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History: III Part 2: The Assyrian and Babylonian Empires and Other States of the Near East, from the Eighth to the Sixth Centuries B.C. (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22717-8.

Web sources

- Lendering, Jona (2006). "Neriglissar". Livius. Retrieved 22 August 2020.

- Radner, Karen (2012). "Sargon II, king of Assyria (721-705 BC)". Assyrian empire builders. Retrieved 9 February 2020.