Samuel de Champlain

Samuel de Champlain (French: [samɥɛl də ʃɑ̃plɛ̃]; c. 13 August 1567[2][Note 1][Note 2] – 25 December 1635) was a French explorer, navigator, cartographer, draftsman, soldier, geographer, ethnologist, diplomat, and chronicler. He made between 21 and 29 trips across the Atlantic Ocean,[3] and founded Quebec, and New France, on 3 July 1608. An important figure in Canadian history, Champlain created the first accurate coastal map during his explorations and founded various colonial settlements.

Samuel de Champlain | |

|---|---|

Detail from "Défaite des Iroquois au Lac de Champlain," Champlain Voyages (1613). This self-portrait is the only surviving contemporary likeness of the explorer.[1] | |

| Born | Samuel Champlain 13 August 1567[2] Brouage or La Rochelle, France |

| Died | 25 December 1635 (aged 68) |

| Other names | "The Father of New France" |

| Occupation(s) | Navigator, cartographer, soldier, explorer, administrator and chronicler of New France |

| Spouse |

Hélène Boullé (m. 1610) |

| Signature | |

Born into a family of sailors, Champlain began exploring North America in 1603, under the guidance of his uncle, François Gravé Du Pont.[4][5] After 1603, Champlain's life and career consolidated into the path he would follow for the rest of his life.[6] From 1604 to 1607, he participated in the exploration and creation of the first permanent European settlement north of Florida, Port Royal, Acadia (1605). In 1608, he established the French settlement that is now Quebec City.[Note 3] Champlain was the first European to describe the Great Lakes, and published maps of his journeys and accounts of what he learned from the natives and the French living among the Natives. He formed long time relationships with local Montagnais and Innu, and, later, with others farther west—tribes of the Ottawa River, Lake Nipissing, and Georgian Bay, and with Algonquin and Wendat. He agreed to provide assistance in the Beaver Wars against the Iroquois. He learned and mastered their languages.

Late in the year of 1615, Champlain returned to the Wendat and stayed with them over the winter, which permitted him to make the first ethnographic observations of this important nation, the events of which form the bulk of his book Voyages et Découvertes faites en la Nouvelle France, depuis l'année 1615 published in 1619.[6] In 1620, Louis XIII of France ordered Champlain to cease exploration, return to Quebec, and devote himself to the administration of the country.[Note 4]

In every way but formal title, Samuel de Champlain served as Governor of New France, a title that may have been formally unavailable to him owing to his non-noble status.[Note 5] Champlain established trading companies that sent goods, primarily fur, to France, and oversaw the growth of New France in the St. Lawrence River valley until his death in 1635. Many places, streets, and structures in northeastern North America today bear his name, most notably Lake Champlain.

Early life

Champlain was born to Antoine Champlain (also written "Anthoine Chappelain" in some records) and Marguerite Le Roy, in either Hiers-Brouage, or the port city of La Rochelle, in the French province of Aunis.

He was born on or before 13 August 1574, according to a recent baptism record found by Jean-Marie Germe, French genealogist.[2][Note 1][8]

Although in 1870, the Canadian Catholic priest Laverdière, in the first chapter of his Œuvres de Champlain, accepted Pierre-Damien Rainguet's[9] estimate of Champlain's birth in 1567 and tried to justify it, his calculations were based on assumptions now believed or proven, to be incorrect.

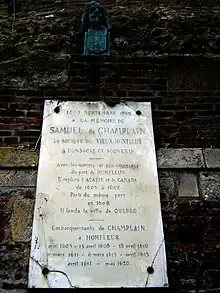

Although Léopold Delayant (member, secretary, then president of l'Académie des belles-lettres, sciences et arts de La Rochelle) wrote as early as 1867 that Rainguet's estimate was wrong, the books of Rainguet and Laverdière have had a significant influence. The 1567 date was carved on numerous monuments dedicated to Champlain and is widely regarded as accurate.

In the first half of the 20th century, some authors disagreed, choosing 1570 or 1575 instead of 1567. In 1978 Jean Liebel published groundbreaking research about these estimates of Champlain's birth year and concluded, "Samuel Champlain was born about 1580 in Brouage, France."[10]

Liebel asserts that some authors, including the Catholic priests Rainguet and Laverdière, preferred years when Brouage was under Catholic control (which include 1567, 1570, and 1575).[11] Champlain claimed to be from Brouage in the title of his 1603 book and to be Saintongeois in the title of his second book (1613).

He belonged to a Roman Catholic family in Brouage which was most of the time a Catholic city, Brouage was a royal fortress and its governor, from 1627 until his death in 1635, was Cardinal Richelieu. The exact location of his birth is thus also not known with certainty, but at the time of his birth his parents were living in Brouage.[Note 6]

Born into a family of mariners (both his father and uncle-in-law were sailors, or navigators), Samuel Champlain learned to navigate, draw, make nautical charts, and write practical reports. His education did not include Ancient Greek or Latin, so he did not read or learn from any ancient literature.

As each French fleet had to assure its own defense at sea, Champlain sought to learn to fight with the firearms of his time: he acquired this practical knowledge when serving with the army of King Henry IV during the later stages of France's religious wars in Brittany from 1594 or 1595 to 1598, beginning as a quartermaster responsible for the feeding and care of horses.

During this time he claimed to go on a "certain secret voyage" for the king,[12] and saw combat (including maybe the Siege of Fort Crozon, at the end of 1594).[13] By 1597 he was a "capitaine d'une compagnie" serving in a garrison near Quimper.[13]

Early travels

In year 3, his uncle-in-law, a navigator whose ship Saint-Julien was to transport Spanish troops to Cádiz pursuant to the Treaty of Vervins, gave Champlain the opportunity to accompany him.

After a difficult passage, he spent some time in Cádiz before his uncle, whose ship was then chartered to accompany a large Spanish fleet to the West Indies, again offered him a place on the ship. His uncle, who gave command of the ship to Jeronimo de Valaebrera, instructed the young Champlain to watch over the ship.[15]

This journey lasted two years and gave Champlain the opportunity to see or hear about Spanish holdings from the Caribbean to Mexico City. Along the way, he took detailed notes, wrote an illustrated report on what he learned on this trip, and gave this secret report to King Henry,[Note 7] who rewarded Champlain with an annual pension.

This report was published for the first time in 1870, by Laverdière, as Brief Discours des Choses plus remarquables que Samuel Champlain de Brouage a reconneues aux Indes Occidentalles au voiage qu'il en a faict en icettes en l'année 1599 et en l'année 1601, comme ensuite (and in English as Narrative of a Voyage to the West Indies and Mexico 1599–1602).

The authenticity of this account as a work written by Champlain has frequently been questioned, due to inaccuracies and discrepancies with other sources on a number of points; however, recent scholarship indicates that the work probably was authored by Champlain.[Note 8]

On Champlain's return to Cádiz in August 1600, his uncle Guillermo Elena (Guillaume Allene),[16] who had fallen ill, asked him to look after his business affairs. This Champlain did, and when his uncle died in June 1601, Champlain inherited his substantial estate. It included an estate near La Rochelle, commercial properties in Spain, and a 150-ton merchant ship.[17]

This inheritance, combined with the king's annual pension, gave the young explorer a great deal of independence, as he did not need to rely on the financial backing of merchants and other investors.[18]

From 1601 to 1603 Champlain served as a geographer in the court of King Henry IV. As part of his duties, he traveled to French ports and learned much about North America from the fishermen that seasonally traveled to coastal areas from Nantucket to Newfoundland to capitalize on the rich fishing grounds there.

He also made a study of previous French failures at colonization in the area, including that of Pierre de Chauvin at Tadoussac.[19] When Chauvin forfeited his monopoly on the fur trade in North America in 1602, responsibility for renewing the trade was given to Aymar de Chaste. Champlain approached de Chaste about a position on the first voyage, which he received with the king's assent.[20]

Champlain's first trip to North America was as an observer on a fur-trading expedition led by François Gravé Du Pont. Du Pont was a navigator and merchant who had been a ship's captain on Chauvin's expedition, and with whom Champlain established a firm lifelong friendship.

He educated Champlain about navigation in North America, including the Saint Lawrence River, and in dealing with the natives there (and in Acadia after).[4] The Bonne-Renommée (the Good Fame) arrived at Tadoussac on March 15, 1603. Champlain was anxious to see for himself all of the places that Jacques Cartier had seen and described sixty years earlier, and wanted to go even further than Cartier, if possible.

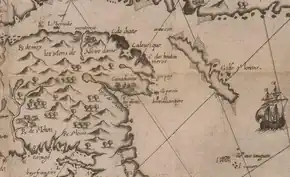

Champlain created a map of the Saint Lawrence on this trip and, after his return to France on 20 September, published an account as Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l'an 1603 ("Concerning the Savages: or travels of Samuel Champlain of Brouages, made in New France in the year 1603").[Note 9]

Included in his account were meetings with Begourat, chief of the Montagnais at Tadoussac, in which positive relationships were established between the French and the many Montagnais gathered there, with some Algonquin friends.

Promising to King Henry to report on further discoveries, Champlain joined a second expedition to New France in the spring of 1604. This trip, once again an exploratory journey without women and children, lasted several years, and focused on areas south of the St. Lawrence River, in what later became known as Acadia. It was led by Pierre Dugua de Mons, a noble and Protestant merchant who had been given a fur trading monopoly in New France by the king. Dugua asked Champlain to find a site for winter settlement.

After exploring possible sites in the Bay of Fundy, Champlain selected Saint Croix Island in the St. Croix River as the site of the expedition's first winter settlement. After enduring a harsh winter on the island the settlement was relocated across the bay where they established Port Royal. Until 1607, Champlain used that site as his base, while he explored the Atlantic coast. Dugua was forced to leave the settlement for France in September 1605, because he learned that his monopoly was at risk. His monopoly was rescinded by the king in July 1607 under pressure from other merchants and proponents of free trade, leading to the abandonment of the settlement.

In 1605 and 1606, Champlain explored the North American coast as far south as Cape Cod, searching for sites for a permanent settlement. Minor skirmishes with the resident Nausets dissuaded him from the idea of establishing one near present-day Chatham, Massachusetts. He named the area Mallebar ("bad bar").[21][22]

Founding of Quebec

In the spring of 1608, Dugua wanted Champlain to start a new French colony and fur trading centre on the shores of the St. Lawrence. Dugua equipped, at his own expense, a fleet of three ships with workers, that left the French port of Honfleur. The main ship, called Don-de-Dieu (French for Gift of God), was commanded by Champlain. Another ship, Lévrier (Hunt Dog), was commanded by his friend Du Pont. The small group of male settlers arrived at Tadoussac on the lower St. Lawrence in June. Because of the dangerous strength of the Saguenay River ending there, they left the ships and continued up the "Big River" in small boats bringing the men and the materials.[Note 10]

Upon arriving in Quebec, Champlain later wrote: "I arrived there on the third of July, when I searched for a place suitable for our settlement; but I could find none more convenient or better suited than the point of Quebec, so called by the savages, which was covered with nut-trees." Champlain ordered his men to gather lumber by cutting down the nut-trees for use in building habitations.[23]

Some days after Champlain's arrival in Quebec, Jean du Val, a member of Champlain's party, plotted to kill Champlain to the end of securing the settlement for the Basques or Spaniards and making a fortune for himself. Du Val's plot was ultimately foiled when an associate of Du Val confessed his involvement in the plot to Champlain's pilot, who informed Champlain. Champlain had a young man deliver Du Val, along with 3 co-conspirators, two bottles of wine and invite the four worthies to an event on board a boat. Soon after the four conspirators arrived on the boat, Champlain had them arrested. Du Val was strangled and hung in Quebec and his head was displayed in the "most conspicuous place" of Champlain's fort. The other three were sent back to France to be tried.[23]

Relations and war with Native Americans

During the summer of 1609, Champlain attempted to form better relations with the local First Nations tribes. He made alliances with the Wendat (called Huron by the French) and with the Algonquin, the Montagnais and the Etchemin, who lived in the area of the St. Lawrence River. These tribes sought Champlain's help in their war against the Iroquois, who lived farther south. Champlain set off with nine French soldiers and 300 natives to explore the Rivière des Iroquois (now known as the Richelieu River), and became the first European to map Lake Champlain. Having had no encounters with the Haudenosaunee at this point many of the men headed back, leaving Champlain with only 2 Frenchmen and 60 natives.

On 29 July, somewhere in the area near Ticonderoga and Crown Point, New York (historians are not sure which of these two places, but Fort Ticonderoga historians claim that it occurred near its site), Champlain and his party encountered a group of Haudenosaunee. In a battle that began the next day, two hundred and fifty Haudenosaunee advanced on Champlain's position, and one of his guides pointed out the three chiefs. In his account of the battle, Champlain recounts firing his arquebus and killing two of them with a single shot, after which one of his men killed the third. The Haudenosaunee turned and fled. While this cowed the Iroquois for some years, they would later return to successfully fight the French and Algonquin for the rest of the century.[Note 11]

The Battle of Sorel occurred on 19 June 1610, with Samuel de Champlain supported by the Kingdom of France and his allies, the Wendat people, Algonquin people and Innu people against the Mohawk people in New France at present-day Sorel-Tracy, Quebec. Champlain's forces armed with the arquebus engaged and slaughtered or captured nearly all of the Mohawks. The battle ended major hostilities with the Mohawks for twenty years.[24]

Marriage

One route Champlain may have chosen to improve his access to the court of the regent was his decision to enter into marriage with the twelve-year-old Hélène Boullé. She was the daughter of Nicolas Boullé, a man charged with carrying out royal decisions at court. The marriage contract was signed on 27 December 1610 in presence of Dugua, who had dealt with the father, and the couple was married three days later. The terms of the contract called for the marriage to be consummated two years later.[25]

Champlain's marriage was initially quite troubled, as Hélène rallied against joining him in August 1613. Their relationship, while it apparently lacked any physical connection, recovered and was apparently good for many years.[26] Hélène lived in Quebec for several years,[27] but returned to Paris and eventually decided to enter a convent. The couple had no children, and Champlain adopted three Montagnais girls named Faith, Hope, and Charity in the winter of 1627–28.

Exploration of New France

On 29 March 1613, arriving back in New France, he first ensured that his new royal commission be proclaimed. Champlain set out on May 27 to continue his exploration of the Huron country and in hopes of finding the "northern sea" he had heard about (probably Hudson Bay). He travelled the Ottawa River, later giving the first description of this area.[Note 12] Along the way, he apparently dropped or left behind a cache of silver cups, copper kettles, and a brass astrolabe dated 1603 (Champlain's Astrolabe), which was later found by a farm boy named Edward Lee near Cobden, Ontario.[28] It was in June that he met with Tessouat, the Algonquin chief of Allumettes Island, and offered to build the tribe a fort if they were to move from the area they occupied, with its poor soil, to the locality of the Lachine Rapids.[22]

By 26 August, Champlain was back in Saint-Malo. There, he wrote an account of his life from 1604 to 1612 and his journey up the Ottawa river, his Voyages[29] and published another map of New France. In 1614, he formed the "Compagnie des Marchands de Rouen et de Saint-Malo" and "Compagnie de Champlain", which bound the Rouen and Saint-Malo merchants for eleven years. He returned to New France in the spring of 1615 with four Recollects in order to further religious life in the new colony. The Roman Catholic Church was eventually given en seigneurie large and valuable tracts of land, estimated at nearly 30% of all the lands granted by the French Crown in New France.[30]

In 1615, Champlain reunited with Étienne Brûlé, his capable interpreter, following separate four-year explorations. There, Brûlé reported North American explorations, including that he had been joined by another French interpreter named Grenolle with whom he had travelled along the north shore of la mer douce (the calm sea), now known as Lake Huron, to the great rapids of Sault Ste. Marie, where Lake Superior enters Lake Huron, some of which was recorded by Champlain.[31][32]

Champlain continued to work to improve relations with the natives, promising to help them in their struggles against the Iroquois. With his native guides, he explored further up the Ottawa River and reached Lake Nipissing. He then followed the French River until he reached Lake Huron.[33]

In 1615, Champlain was escorted through the area that is now Peterborough, Ontario by a group of Wendat. He used the ancient portage between Chemong Lake and Little Lake (now Chemong Road) and stayed for a short period of time near what is now Bridgenorth.[34]

Military expedition

On 1 September 1615, at Cahiagué (a Wendat community on what is now called Lake Simcoe), he and the northern tribes started a military expedition against the Iroquois. The party passed Lake Ontario at its eastern tip where they hid their canoes and continued their journey by land. They followed the Oneida River until they arrived at the main Onondaga fort on October 10. The exact location of this place is still a matter of debate. Although the traditional location, Nichols Pond, is regularly disproved by professional and amateur archaeologists, many still claim that Nichols Pond is the location of the battle, 10 miles (16 km) south of Canastota, New York.[35] Champlain attacked the stockaded Oneida village. He was accompanied by 10 Frenchmen and 300 Wendat. Pressured by the Huron Wendat to attack prematurely, the assault failed. Champlain was wounded twice in the leg by arrows, one in his knee. The conflict ended on October 16 when the French Wendat were forced to flee.

Although he did not want to, the Wendat insisted that Champlain spend the winter with them. During his stay, he set off with them in their great deer hunt, during which he became lost and was forced to wander for three days living off game and sleeping under trees until he met up with a band of First Nations people by chance. He spent the rest of the winter learning "their country, their manners, customs, modes of life". On 22 May 1616, he left the Wendat country and returned to Quebec before heading back to France on 2 July.

Improving administration in New France

Champlain returned to New France in 1620 and was to spend the rest of his life focusing on administration of the territory rather than exploration. Champlain spent the winter building Fort Saint-Louis on top of Cape Diamond. By mid-May, he learned that the fur trading monopoly had been handed over to another company led by the Caen brothers. After some tense negotiations, it was decided to merge the two companies under the direction of the Caens. Champlain continued to work on relations with the natives and managed to impose on them a chief of his choice. He also negotiated a peace treaty with the Iroquois.

Champlain continued to work on the fortifications of what became Quebec City, laying the first stone on 6 May 1624. On 15 August he once again returned to France where he was encouraged to continue his work as well as to continue looking for a passage to China, something widely believed to exist at the time. By July 5 he was back at Quebec and continued expanding the city.

In 1627 the Caen brothers' company lost its monopoly on the fur trade, and Cardinal Richelieu (who had joined the Royal Council in 1624 and rose rapidly to a position of dominance in French politics that he would hold until his death in 1642) formed the Compagnie des Cent-Associés (the Hundred Associates) to manage the fur trade. Champlain was one of the 100 investors, and its first fleet, loaded with colonists and supplies, set sail in April 1628.[37]

Champlain had overwintered in Quebec. Supplies were low, and English merchants sacked Cap Tourmente in early July 1628.[38] A war had broken out between France and England, and Charles I of England had issued letters of marque that authorized the capture of French shipping and its colonies in North America.[39] Champlain received a summons to surrender on July 10 from the Kirke brothers, two Scottish brothers who were working for the English government. Champlain refused to deal with them, misleading them to believe that Quebec's defenses were better than they actually were (Champlain had only 50 pounds of gunpowder to defend the community). Successfully bluffed, they withdrew, but encountered and captured the French supply fleet, cutting off that year's supplies to the colony.[40] By the spring of 1629 supplies were dangerously low and Champlain was forced to send people to Gaspé and into Indian communities to conserve rations.[41] On July 19, the Kirke brothers arrived before Quebec after intercepting Champlain's plea for help, and Champlain was forced to surrender the colony.[42] Many colonists were transported first to England and then to France by the Kirkes, but Champlain remained in London to begin the process of regaining the colony. A peace treaty had been signed in April 1629, three months before the surrender, and, under the terms of that treaty, Quebec and other prizes that were taken by the Kirkes after the treaty were to be returned.[43] It was not until the 1632 Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, however, that Quebec was formally given back to France. (David Kirke was rewarded when Charles I knighted him and gave him a charter for Newfoundland.) Champlain reclaimed his role as commander of New France on behalf of Richelieu on 1 March 1633, having served in the intervening years as commander in New France "in the absence of my Lord the Cardinal de Richelieu" from 1629 to 1635.[44] In 1632 Champlain published Voyages de la Nouvelle-France, which was dedicated to Cardinal Richelieu, and Traitté de la marine et du devoir d'un bon marinier, a treatise on leadership, seamanship, and navigation. (Champlain made more than twenty-five round-trip crossings of the Atlantic in his lifetime, without losing a single ship.)[45]

Last return, and last years working in Quebec

Champlain returned to Quebec on 22 May 1633, after an absence of four years. Richelieu gave him a commission as Lieutenant General of New France, along with other titles and responsibilities, but not that of governor. Despite this lack of formal status, many colonists, French merchants, and Indians treated him as if he had the title; writings survive in which he is referred to as "our governor".[46] On 18 August 1634, he sent a report to Richelieu stating that he had rebuilt on the ruins of Quebec, enlarged its fortifications, and established two more habitations. One was 15 leagues upstream, and the other was at Trois-Rivières. He also began an offensive against the Iroquois, reporting that he wanted them either wiped out or "brought to reason".

Death and burial

Champlain had a severe stroke in October 1635, and died on 25 December, leaving no immediate heirs. Jesuit records state he died in the care of his friend and confessor Charles Lallemant.

Although his will (drafted on 17 November 1635) gave much of his French property to his wife Hélène Boullé, he made significant bequests to the Catholic missions and to individuals in the colony of Quebec. However, Marie Camaret, a cousin on his mother's side, challenged the will in Paris and had it overturned. It is unclear exactly what happened to his estate.[47][48][49]

Samuel de Champlain was temporarily buried in the church while a standalone chapel was built to hold his remains in the upper part of the city. This small building, along with many others, was destroyed by a large fire in 1640. Though immediately rebuilt, no traces of it exist anymore: his exact burial site is still unknown, despite much research since about 1850, including several archaeological digs in the city. There is general agreement that the previous Champlain chapel site, and the remains of Champlain, should be somewhere near the Notre-Dame de Québec Cathedral.[50][51]

The search for Champlain's remains supplies a key plot-line in the crime writer Louise Penny's 2010 novel, Bury Your Dead.[52]

Legacy

.jpg.webp)

Many sites and landmarks have been named to honour Champlain, who was a prominent figure in many parts of Acadia, Ontario, Quebec, New York, and Vermont. Memorialized as the "Father of New France" and "Father of Acadia", his historic significance endures in modern times. Lake Champlain, which straddles the border between northern New York and Vermont, extending slightly across the border into Canada, was named by him, in 1609, when he led an expedition along the Richelieu River, exploring a long, narrow lake situated between the Green Mountains of present-day Vermont and the Adirondack Mountains of present-day New York. The first European to map and describe it, Champlain claimed the lake as his namesake.

Memorials include:

- Lake Champlain, Champlain Valley, the Champlain Trail Lakes.

- Champlain Sea: a past inlet of the Atlantic Ocean in North America, over the St. Lawrence, the Saguenay, and the Richelieu rivers, to over Lake Champlain, which inlet disappeared many thousands years before Champlain was born.

- Champlain Mountain, Acadia National Park – which he first observed in 1604.[53]

- A town and village in New York, as well as a township in Ontario and a municipality in Quebec.

- The provincial electoral district of Champlain, Quebec, and several defunct electoral districts elsewhere in Canada.

- Samuel de Champlain Provincial Park, a provincial park in northern Ontario near the town of Mattawa.

- Champlain Bridge, which connects the island of Montreal to Brossard, Quebec across the St. Lawrence.

- Champlain Bridge, which connects the cities of Ottawa, Ontario and Gatineau, Quebec.

- Champlain College, one of six colleges at Trent University in Peterborough, Ontario, is named in his honour.

- Fort Champlain, a dormitory at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario; named in his honour in 1965, it houses the 10th cadet squadron.

- A French school in Saint John, New Brunswick; École Champlain, an elementary school in Moncton, New Brunswick and one in Brossard; Champlain College, in Burlington, Vermont; and Champlain Regional College, a CEGEP with three campuses in Quebec.

- Marriott Château Champlain hotel, in Montreal.

- Streets named Champlain in numerous cities, including Quebec, Shawinigan, the city of Dieppe in the province of New Brunswick, in Plattsburgh, and no less than eleven communities in northwestern Vermont.

- A garden called Jardin Samuel-de-Champlain in Paris, France.

- A memorial statue on Cumberland Avenue in Plattsburgh, New York on the shores of Lake Champlain in a park named for Champlain.

- A memorial statue in Saint John, New Brunswick, Canada in Queen Square that commemorates his discovery of the Saint John River.[54]

- A memorial statue in Isle La Motte, Vermont, on the shore of Lake Champlain.

- The lighthouse at Crown Point, New York features a statue of Champlain by Carl Augustus Heber.

- A commemorative stamp issue in May 2006 jointly by the United States Postal Service and Canada Post.[55]

- A statue in Ticonderoga, New York, unveiled in 2009 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Champlain's exploration of Lake Champlain.

- A statue in Orillia, Ontario at Couchiching Beach Park on Lake Couchiching. This statue was removed by Parks Canada, and is not likely to be returned, as it incorporated offensive depictions of First Nations peoples.[56]

- HMCS Champlain (1919), a S class destroyer that served in the Royal Canadian Navy from 1928 to 1936.

- HMCS Champlain, a Canadian Forces Naval Reserve division based in Chicoutimi, Quebec since activation in 1985.

- Champlain Place, a shopping centre located in Dieppe, New Brunswick, Canada.

- The Champlain Society, a Canadian historical and text publication society, chartered in 1927.

- A memorial statue in Ottawa at Nepean Point, by Hamilton MacCarthy. The statue depicts Champlain holding an astrolabe (upside-down, as it happens). It did previously include an "Indian Scout" kneeling at its base. In the 1990s, after lobbying by Indigenous people, it was removed from the statue's base, renamed and placed as the "Anishinaabe Scout" in Major's Hill Park.

Bibliography

These are works that were written by Champlain:

- Brief Discours des Choses plus remarquables que Sammuel Champlain de Brouage a reconneues aux Indes Occidentalles au voiage qu'il en a faict en icettes en l'année 1599 et en l'année 1601, comme ensuite (first French publication 1870, first English publication 1859 as Narrative of a Voyage to the West Indies and Mexico 1599–1602)

- Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l'an 1603 (first French publication 1604, first English publication 1625)

- Voyages de la Nouvelle-France (first French publication 1632)

- Traitté de la marine et du devoir d'un bon marinier (first French publication 1632)

Notes and references

Notes

- For a detailed analysis of his baptismal record, see Ritch

- The baptism act does not contain information about the age of Samuel, neither his birth date nor his place of birth.

- Thanks to Pierre Dugua de Mons, who fully financed—at a loss—the first years of both French settlements in North America (first Acadia, then Quebec).

- According to Trudel (1979), Louis was 18 years old, an inexperienced minor (when age of majority was 25), and Champlain was lieutenant to the Prince de Condé, the viceroy of New France since 1612, who, as Trudel writes, "was liberated [from jail, where he been for 3 years] in October 1619, and yielded his rights as viceroy to Henri II de Montmorency, admiral of France. The latter confirmed Champlain in his office [...]. On 7 May 1620, Louis XIII wrote to Champlain to enjoin him to maintain the country 'in obedience to me, making the people who are there live as closely in conformity with the laws of my kingdom as you can.' From that moment Champlain was to devote himself exclusively to the administration of the country; he was to undertake no further great voyages of discovery; his career as an explorer had ended."

- Some say that the King of France made him his "royal geographer", but it is unproven and may only come from Marc Lescarbot books: Champlain never used that title. The honorific "de" was only added to his name from 1610, when he was already well-known, right after his patron, King Henry IV, was murdered. This usage by a non-noble was tolerated so that he would continue to gain access to the court during the long regency of King Louis XIII (who was only eight years old at the death of his father). Champlain received the official title of "lieutenant" (adjunct representative) of whichever noble was designated as Viceroy of New France, the first being Pierre Dugua, Sieur de Mons. In 1629, Champlain was named "commandant" under the authority of the King Minister, Richelieu. It was Champlain's successor, Charles Jacques Huault de Montmagny, who was the first to be formally named as the governor of New France, when he moved to Quebec City in 1636 and became the first noble to live there in that century.

- His family lived in Brouage at the time of his birth; the exact place and date of his birth are unknown.Britannica.com Archived 2009-04-14 at the Wayback Machine

- Three different handwritten copies of this report still exist. One of them is at the John Carter Brown Library at Brown University.

- For a detailed treatment of claims against Champlain's authorship, see the chapter by François-Marc Gagnon in Litalien (2004), pp. 84ff. Fischer (2008), pp. 586ff also addresses these claims and accepts Champlain's authorship.

- Champlain did not begin using the honorific de in his name until at least 1610 when he married, the year King Henry was murdered. A reprint of this book in 1612 was credited to "Sieur de Champlain, civilization.ca Archived 2007-03-11 at the Wayback Machine

- Only at his last arrival (in 1633), Champlain did not leave the ships at Tadoussac but sailed them directly to Quebec City.Trudel (1979)

- In 1701, The Great Peace Treaty was signed in Montreal, involving the French and every Indigenous nation coming or living on the shores of the Saint Lawrence River except maybe in wintertime.

- In 1953, a rock was found at a location now known as the Champlain lookout, which bore the inscription "Champlain juin 2, 1613". What about this finding?

Citations

- Fischer (2008), p. 3

- Fichier Origine

- "Samuel de Champlain". Encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 2020-04-26. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- d'Avignon (2008)

- Vaugeois (2008)

- Heidenreich, Conrad E.; Ritch, K. Janet, eds. (2010). Samuel de Champlain before 1604: Des Sauvages and Other Documents Related to the Period. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 16. doi:10.3138/9781442620339. ISBN 978-0-7735-3756-9.

- Bishop (1948), pp 6–7

- Germe, p. 2

- Rainguet (1851)

- Liebel (1978), p. 236

- Liebel (1978), pp. 229–237.

- Fischer (2008), p. 62

- Fischer (2008), p. 65 Note: Fischer cites numerous other authorities in repeating this.

- Weber (1967)

- Litalien (2004), p. 87

- Heidenreich, Conrad E.; Ritch, K. Janet, eds. (2010). Samuel de Champlain before 1604: Des Sauvages and Other Documents Related to the Period. The Publications of the Champlain Society. p. 14. doi:10.3138/9781442620339. ISBN 978-0-7735-3756-9.

- Fischer (2008), pp. 98–99

- Fischer (2008), p. 100

- Fischer (2008), pp. 100–117

- Fischer (2008), pp. 121–123

- NPS

- Vermont Map

- "Founding of Quebec | Early Americas Digital Archive (EADA)". eada.lib.umd.edu. Archived from the original on 2021-04-21. Retrieved 2021-02-20.

- Fischer (2008), pp. 577–578

- Fischer (2008), pp. 287–288

- Fischer (2008), pp. 313–316

- Fischer (2008), pp. 374–5

- Brebner, John Bartlett (1966). The Explorers of North America, 1492–1806. Cleveland, Ohio: The World Publishing Company. p. 135.

- Champlain (1613)

- Dalton (1968)

- Butterfield, Consul Willshire (1898). History of Brulé's Discoveries and Explorations, 1610–1626. Cleveland, Ohio: Helman-Taylor. pp. 49–51.(online: archive.org, Library of Congress Archived 2018-10-03 at the Wayback Machine)

- "The Explorers Étienne Brûlé 1615-1621". Virtual Museum of New France. Canadian Museum of History. Archived from the original on 24 March 2019. Retrieved 7 April 2019.

- "Samuel de Champlain: timeline". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2019.

- Williams, Doug (September 8, 2015). "A small man with a big gun". Peterborough Examiner. Archived from the original on February 20, 2018. Retrieved 2018-02-20.

- Weiskotten (1998)

- Guizot, p. 190

- Fischer (2008), pp. 404–410

- Fischer (2008), pp. 410–412

- Fischer (2008), p. 409

- Fischer (2008), pp. 412–415

- Fischer (2008), pp. 418–420

- Fischer (2008), p. 421

- Fischer (2008), p. 428

- Trudel (1979)

- Fischer (2008), p. 447

- Fischer (2008), pp. 445–446

- Fischer (2008), p. 520

- Heidenreich

- Le Blant (1964), pp 425–437

- Champlain: Travels in the Canadian Francophonie

- La Chappelle

- Penny (2010)

- Acadia National Park

- Saint John Additional Information Archived September 27, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Gicker (2006)

- "Orillia's Champlain monument restoration on hold". 18 July 2018. Archived from the original on 12 November 2019. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

References

- "Acadia National Park". Oh Ranger. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- Bishop, Morris (1948). Samuel de Champlain: The Life of Fortitude. New York: Knopf.

- Champlain, Samuel (1613). Les voyages du Sieur de Champlain, Saintongeois, capitaine ordinaire pour le Roy en la Marine (in French). J. Berjon.

- Dalton, Roy C. (1968). The Jesuit Estates Question, 1760–88. University of Toronto Press. p. 60.

- d'Avignon (Davignon), Mathieu (2008). Champlain et les fondateurs oubliés, les figures du père et le mythe de la fondation (in French). Quebec City: Les Presses de l'Université Laval (PUL). p. 558. ISBN 978-2-7637-8644-5. Note: Mathieu d'Avignon (Ph.D. in history, Laval University, 2006) is an affiliate researcher into the University of Quebec at Chicoutimi Research Group on History. He is preparing a special new full edition, in modern French, of Champlain's Voyages in New France.

- Germe, Jean-Marie (April 15, 2012). "Journal le Soleil": 2.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Champlain (de), Samuel". Fichier Origine (in French). Archived from the original on 2014-09-15. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- "La chapelle et le tombeau de Champlain : état de la question" (in French). Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- Fischer, David Hackett (2008). Champlain's Dream. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4165-9332-4. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- Gicker, William J., ed. (2006). "Samuel de Champlain 39¢ (USA); Samuel de Champlain 51¢ (Canada)". USA Philatelic. 11 (3): 7.

This souvenir sheet celebrates the 400th anniversary of the explorations of Samuel de Champlain in 1606.

- Guizot, François Pierre Guillaume. "Chapter 53". A Popular History of France from the Earliest Times. Vol. 6. Black, Robert (trans). Boston: Dana Estes & Charles E. Lauriat (Imp.).

- Heidenreich, Conrad E. (August 8, 2008). Who was Champlain? His Family and Early Life. Métis sur mer. Archived from the original on May 12, 2013.

This lecture is based on parts of a book by Conrad E. Heidenreich and K. Janet Ritch soon to by published by The Champlain Society, provisionally entitled: The Works of Samuel de Champlain: Des Sauvages and other Documents Related to the Period before 1604.

- Le Blant, Robert (1964). "Le triste veuvage d'Hélène Boullé" [The sad widow of Hélène Boullé] (PDF). Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française (in French). 18 (3): 425. doi:10.7202/302392ar. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-10-09.

- Liebel, Jean (September 1978). "On a vieilli Champlain" [They made Champlain older]. La Revue d'histoire de l'Amérique française (in French). 32 (2): 229–237. doi:10.7202/303691ar. Archived from the original on 2012-06-29. Retrieved 2009-06-01.

- Litalien, Raymonde; Vaugeois, Denis, eds. (2004). Champlain: the Birth of French America. Roth, Käthe (trans). McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 0-7735-2850-4. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- "Malle Barre (Modern Nauset Harbor, Eastham, MA)". Archeology Program. National Park Service. Archived from the original on September 4, 2015. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- Penny, Louise (2010). Bury Your Dead. New York: Minotaur. ISBN 978-0-3123-7704-5.

- Rainguet, Pierre-Damien (1851). Biographie Saintongeaise ou Dictionnaire Historique de Tous les Personnages qui se sont Illustrés dans les Anciennes Provinces de Saintonge et d'Aunis jusqu'à Nos Jours (in French). Saintes, France: M. Niox. OCLC 466560584. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- Ritch, Janet. "Discovery of the Baptismal Certificate of Samuel de Champlain". The Champlain Society. Archived from the original on 2013-12-05. Retrieved 2013-10-03.

- "Samuel de Champlain's Voyages". Travel Vermont. Archived from the original on November 11, 2010. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- "Time Periods – Life and Death of Champlain". Champlain : Travels in the Canadian Francophonie. Archived from the original on 2015-07-22. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- Trudel, Marcel (1979) [1966]. "Samuel de Champlain". In Brown, George Williams (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. I (1000–1700) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 2009-05-28.

- Vaugeois, Denis (June 2, 2008). Champlain et Dupont Gravé en contexte. 133e congrès du comtié des travaux historiques et scientifiques (CTHS) (in French). Québec City. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013.

- Weber, E. L. (Sculptor). "Samuel de Champlain, (sculpture)". Art Inventories Catalog. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on 2015-09-04. Retrieved 2015-07-21.

- Weiskotten, Daniel H. (July 1, 1998). "The Real Battle of Nichols Pond". Roots Web, Ancestry.com. Archived from the original on 2013-05-27. Retrieved 2013-07-12.

Further reading

| Library resources about Samuel de Champlain |

| By Samuel de Champlain |

|---|

- Champlain, Samuel de (2005). Voyages of Samuel de Champlain, 1604–1918: with a map and two plans. Elibron Classics. ISBN 1-4021-2853-3. Archived from the original on 2023-04-19. Retrieved 2020-11-20.

- Dix, Edwin Asa. (1903). Champlain, the Founder of New France Archived 2023-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, IndyPublish ISBN 1-4179-2270-2

- Laverdière, Abbé Charles-Honoré Cauchon (1870). Œuvres de Champlain (in French). Quebec City: Desbarats.

Œuvres de Champlain.

- Morganelli, Adrianna (2006). Samuel de Champlain: from New France to Cape Cod. Crabtree Pub. ISBN 978-0-7787-2414-8.

Samuel de Champlain.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot, (1972). Samuel de Champlain: Father of New France Little Brown, ISBN 0-316-58399-5

- Sherman, Josepha (2003). Samuel de Champlain, Explorer of the Great Lakes Region and Founder of Quebec. Group's Rosen Central. ISBN 0-8239-3629-5.

Samuel de Champlain.

External links

![]() Media related to Samuel de Champlain at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Samuel de Champlain at Wikimedia Commons

- Works by Samuel de Champlain at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Samuel de Champlain at Faded Page (Canada)

- Works by or about Samuel de Champlain at Internet Archive

- From Marcel Trudel: Champlain, Samuel de Archived 2017-09-21 at the Wayback Machine (at The Canadian Encyclopedia)

- Champlain in Acadia

- Biography at the Museum of Civilization

- Samuel de Champlain Biography by Appleton and Klos

- Description of Champlain's voyage to Chatham, Cape Cod in 1605 and 1606.

- They Didn't Name That Lake for Nothing, Sunday Book Review, The New York Times, October 31, 2008

- Dead Reckoning – Champlain in America, PBS documentary 2009

- World Digital Library presentation of Descripsion des costs, pts., rades, illes de la Nouuele France faict selon son vray méridienor Description of the Coasts, Points, Harbours and Islands of New France. Library of Congress. Primary source portolan style chart on vellum with summary description, image with enhanced view and zoom features, text to speech capability. French. Links to related content. Content available as TIF. One of the major cartographic resources, this map offers the first thorough delineation of the New England and Canadian coasts from Cape Sable to Cape Cod.

- A book from 1603 of Champlain's first voyage to New France from the World Digital Library

- (in French) Champlain's tomb: State of the Art Inquiry

- (in French) From Samuel de Champlain: Les Voyages de la Nouvelle France... (1632) (at Rare Book Room)

- (in French) Baptismal parish register, August 13, 1574, protestant temple Saint.Yon, La Rochelle

- (in French) Digitized copy of Champlain's Des Sauvages from the John Carter Brown Library