Charles Ewart

Cornet Charles Ewart (1769 – 23 March 1846) was a Scottish soldier of the Royal North British Dragoons (more commonly known as the Scots Greys), famous for capturing the regimental eagle of the 45e Régiment de Ligne (lit. '45th Regiment of the Line') at the Battle of Waterloo.

He was born near Kilmarnock (although recent research has found that he may have in fact been born nearer Moffat) in 1769, and enlisted in the dragoons at the age of twenty. He fought in a number of actions in the French Revolutionary Wars, was briefly taken prisoner, and emerged from the conflict as a sergeant in the regiment. Over the next two decades he became a well-respected and competent soldier, serving as fencing-master of the regiment; a heavily built man, reported as 6'4" tall and "of Herculean strength" he was an expert swordsman and accomplished rider.[1] At the Battle of Waterloo, he captured one of the two imperial eagle standards captured by the British Army during the Waterloo campaign. The year after Waterloo he was made a commissioned officer with the junior-most rank of ensign, retiring in 1821.

The engagement

At Waterloo, the Scots Greys were part of the Union Brigade, a formation of heavy cavalry regiments held in reserve by Wellington and consisting of the 1st (Royal) Regiment of Dragoons, the 2nd (Royal North British) Dragoons, and the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons. In the line of battle, General Thomas Picton's 5th Division was held in reserve, on the left of the Allied line, behind the Dutch-Belgian 2nd Division. The 5th contained a number of experienced veteran units from the Peninsular War, including the 92nd Foot (Gordon Highlanders).

After a heavy exchange of fire, the Belgians were forced to fall back to the far side of the ridge on which they were stationed, and the 5th Division moved forward over the crest of the ridge to hold the line. After the heavy exchange of fire continued, with the 5th holding firm, it was decided that the division should charge to break up the French columns; the cavalry held in reserve were brought forward, and passed through the ranks of the infantry and into action.

At this point, the Gordon Highlanders were exchanging fire with the 1st Battalion of the 45th, which was deploying around thirty yards to their front. The Greys quickly and unexpectedly passed through the infantry, moved forward the short distance between the lines, and broke through to the centre of the French infantry as it was forming into a defensive line. In the confusion that followed, the 45th was effectively broken as an organised unit, and the eagle it carried was quickly seized by Sergeant Ewart, in close fighting with a number of Frenchmen.

One made a thrust at my groin, I parried him off and cut him down through the head. A lancer came at me - I threw the lance off by my right side and cut him through the chin and upwards through the teeth. Next, a foot soldier fired at me and then charged me with his bayonet, which I also had the good luck to parry, and then I cut him down through the head.

To prevent it being recaptured, he was ordered to take it to safety; he did, but paused for some time overlooking the battlefield before finally carrying the trophy to Brussels. Whilst the brigade had not taken significant losses, they were disorganised, and carried forward to attack French artillery; charged by French cavalry in turn, they took heavy losses, and played no further part in the battle.

The reminiscences of James Paterson

James Paterson was a printer, editor, and historian born and based mostly in Ayrshire throughout his working life. In 1846 he and several others dined with Charles Ewart at the Monument Inn in Kilmarnock and published the story of this Ayrshire hero in The Observer:[2]

_(14576986319).jpg.webp)

Charles Ewart was about 6 feet high, firmly knit, with a countenance indicative of high mental and physical energies.

In the retreat of the British through Holland after the disastrous siege of Nijmegen, 27 October to 8 November 1794, Ewart one day heard the wailing sounds of a child coming from close to the roadside. He dismounted and found a woman and child lying in the snow. The mother was dead, but the infant, still clinging to life, was in the act of suckling from the breast of its lifeless parent. Ewart rescued the baby and on reaching the encampment for the evening, met with his colonel who offered to defray the expenses of a wet nurse. Great difficulties were encountered in this, however he was successful and also fortunate in discovering the father of the child, a sergeant in the 60th regiment. Some years later the father, now a sergeant-major and father of a healthy son, fortuitously met with Ewart. He tried to give Ewart a sum of money, which upon being firmly rejected, was replaced with the gift of a silver watch, and this was finally accepted as a memento of the events.

At Waterloo, Ewart was involved in a hand to hand combat with an officer, whom he was about to cut down, when a young ensign of the Greys offered to instead take the Frenchman to the rear as a prisoner. No sooner had he agreed to the request when he heard the report of a pistol and upon turning, saw the ensign falling from his horse, and the officer in the act of replacing the weapon with which he had dispatched the life of his preserver. Thus enraged, Ewart cut down the officer, deaf to his pleadings for mercy. Dashing forward he now found himself close to the standard-bearer of one of the French Invincible regiments. A short and deadly conflict ensued and as the staff had stuck fast in the ground he was able to lay hold of it without further trouble. Looking round he saw a lancer single him out, gallop forward and hurl his spear at his breast. He had just enough strength to ward off the blow, so that the lance only grazed his side; then raising himself up in his stirrups, he brought his opponent to the ground with one cut of his sword. When riding away with the Eagle he experienced another narrow escape, for a wounded Frenchman, who he had taken for dead, raised himself up on one elbow and fired at him as he passed. The ball fortunately missed him and he was able to take his prize to the rear.

In 1816 he was invited to a Waterloo dinner at Leith near Edinburgh, where Sir Walter Scott proposed his health and invited him to speak. Lieutenant Ewart begged that he might be excused, saying that he would rather fight the battle of Waterloo over again, than face so large an assemblage.

— James Paterson, Autobiographical Remininscences, 1876, pp. 205–213.

The legend

The capture of the eagle is one of the most prized honours of the Scots Greys and, in commemoration of this, their cap badge shows the eagle. As with many such incidents, the story of the capture has grown greatly over the years, to the status of a legend; it is often told that the Greys charged the 45th, with the Gordons seizing hold of their stirrup-leathers and carrying themselves along into the fray, crying "Scotland Forever!" On the contrary, modern research suggests that there was no charge, but rather a quick walk (commonly used by large cavalry formations to preserve order when speed of arrival is irrelevant) into the advancing French line. The rest of the British Army called the Greys The Birdcatchers, as a wry nickname for the eagles capture.[3]

Throughout the entire Waterloo campaign two French Eagles were captured during battle, both by the Union Brigade in this particular action. Ewart was hailed a hero, honoured, and travelled the country giving speeches. He was given a commission as an ensign (a second lieutenancy) in the 5th Veteran Battalion in 1816, and left the army when this unit was disbanded in 1821.

Later life

He lived in Salford, and in his final years at Davyhulme, near Manchester, retiring on the full pay of an ensign.

Death

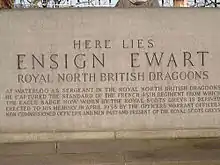

Ewart died in 1846. His body was buried in the New Jerusalem Chapel graveyard in Bolton Street, Salford. His memorial read "In Memory of Ensign Charles Ewart, who departed March 23, 1846, aged 77 years". The grave was paved over and forgotten for many years, being uncovered in the 1930s, and his body was reburied by the Royal Scots Greys (as they were then titled) on the esplanade of Edinburgh Castle in 1938.

Today, he is best known to the general populace by a pub in Edinburgh which bears his name, the Ensign Ewart; it is located next to the Castle esplanade, where a monument marks his burial place.

References

- Waterloo Battlefield Tours. Archived July 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Paterson, James (1876). Autobiographical Remininscences. Glasgow: Maurice Ogle & Co. pp. 205–213. ISBN 9781230283883.

- British Battles website.

- Royal Scots Greys at Waterloo, from the Napoleonic Alliance Gazette

- Charles Ewart

- Obituary and notes in The Times, 8 April 1846, p. 8