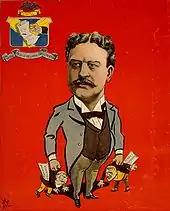

Charles Yerkes

Charles Tyson Yerkes Jr. (/ˈjɜːrkiːz/ YUR-keez; June 25, 1837 – December 29, 1905) was an American financier. He played a part in developing mass-transit systems in Chicago and London.

Charles Yerkes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Charles Tyson Yerkes June 25, 1837 Northern Liberties, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | December 29, 1905 (aged 68) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Entrepreneur and investor |

| Known for | Urban transit finance |

| Spouses |

|

| Parent(s) | Charles Tyson Yerkes Sr. and Elizabeth Link Yerkes |

| Signature | |

Philadelphia

Yerkes was born into a Quaker family[1] in the Northern Liberties, a district adjacent to Philadelphia, on June 25, 1837.[2] His mother, Elizabeth Link Yerkes, died of puerperal fever when he was five years old, and shortly thereafter his father Charles Tyson Yerkes Sr. was expelled from the Society of Friends for marrying a non-Quaker. After finishing a two-year course at Philadelphia's Central High School, Yerkes began his business career at the age of 17 as a clerk in a local grain brokerage. In 1859, aged 22, he opened his own brokerage firm and joined the Philadelphia stock exchange.

By 1865, he had moved into banking and specialized in selling municipal, state, and government bonds. Relying on his bank president father's connections, his political contacts, and his own acumen, Yerkes gained a name for himself in the local financial and social world. While serving as a financial agent for the City of Philadelphia's treasurer, Joseph Marcer, Yerkes risked public money in a large-scale stock speculation. This speculation ended calamitously when the Great Chicago Fire sparked a financial panic. Left insolvent and unable to make payment to the City of Philadelphia, Yerkes was convicted of larceny and sentenced to thirty-three months in Eastern State Penitentiary.

In an attempt to remain out of prison, he attempted to blackmail two influential Pennsylvania politicians. The blackmail plan initially failed; the damaging information on these politicians was eventually made public and political leaders, including then-President Ulysses S. Grant, feared that the revelations might harm their prospects in the upcoming elections. Yerkes was promised a pardon if he would deny the accusations he had made. He agreed to these terms and was released after serving seven months in prison.[3]

Chicago

In 1881 Yerkes traveled to Fargo in the Dakota Territory to obtain a divorce from his wife. Later that year, he remarried and moved to Chicago. There, he opened a stock and grain brokerage but soon became involved with planning the city's public transportation system. In 1886, Yerkes and his business partners used a complex financial deal to take over the North Chicago Street Railway and then proceeded to follow this with a string of further takeovers until he controlled a majority of Chicago's street railway systems on the north and west sides. Yerkes was not averse to using bribery and blackmail to obtain his ends.[3]

In an effort to improve his public image, Yerkes decided in 1892 to bankroll the world's largest telescope after being lobbied by the astronomer George Ellery Hale and University of Chicago president William Rainey Harper. He had initially intended to finance only a telescope but eventually agreed to foot the bill for an entire observatory. He contributed nearly $300,000 to the University of Chicago to establish what would become known as the Yerkes Observatory, located in Williams Bay, Wisconsin.

In 1895, Yerkes purchased the Republican partisan newspaper, the Chicago Inter Ocean, using the publication to support his political agenda.[4]

Yerkes embarked upon a campaign for longer streetcar franchises in 1895, but Illinois governor John Peter Altgeld vetoed the franchise bills. Yerkes renewed the campaign in 1897, and, after a hard-fought battle, secured from the Illinois Legislature a bill granting city councils the right to approve extended franchises. The so-called franchise war then shifted to the Chicago City Council — an arena in which Yerkes ordinarily thrived. A partially reformed council under Mayor Carter Harrison Jr., however, ultimately defeated Yerkes, with the swing votes coming from aldermen "Hinky Dink" Kenna and "Bathhouse" John Coughlin.

In 1899, Yerkes sold the majority of his Chicago transport stocks and moved to New York.[1]

Art collection

While living in Chicago, Yerkes became an art collector, relying on Sarah Tyson Hallowell (1846–1924) to advise him on his purchases. After the Chicago World's Fair in 1893, she tried to interest him in the works of Auguste Rodin, which were part of the loan exhibitor of French art. Because the subject matter was controversial, Yerkes initially turned the works down, but he soon changed his mind and acquired two Rodin marbles, Cupid and Psyche and Orpheus, for his Chicago mansion, the first two of Rodin's works known to have been sold to an American collector. Yerkes' art collection also included works by the French academic painters, such as Pygmalion and Galatea by Jean-Léon Gérôme and works by William-Adolphe Bouguereau and members of the Barbizon School. In 1904, he published a two volume catalog of his collection, which by that time was in New York:

- Catalogue of paintings and sculpture in the collection of Charles T. Yerkes, esq., New York, 1904

London

In August 1900, Yerkes became involved in the development of the London underground railway system after riding along the route of one proposed line and surveying the city of London from the summit of Hampstead Heath. He established the Underground Electric Railways Company of London to take control of the District Railway and the partly built Baker Street and Waterloo Railway, Charing Cross, Euston and Hampstead Railway, and Great Northern, Piccadilly and Brompton Railway.[1] Yerkes employed complex financial arrangements similar to those that he had used in the United States to raise the funds necessary to construct the new lines and electrify the District Railway (today known as the District line). In one of his last great triumphs, Yerkes managed to thwart an attempt by J. P. Morgan to enter the London underground railway field.[1] Yerkes did not live to see his London tube lines in operation. The now Bakerloo and Piccadilly lines opened in 1906, a few months after his death, and the Charing Cross line (today part of the Northern line) the following summer.

Death and legacy

Yerkes died at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York on December 29, 1905, of kidney disease.[7] The events of Yerkes's life served as a blueprint for the Theodore Dreiser novels The Financier, The Titan, and The Stoic,[3] in which Yerkes was fictionalized as Frank Cowperwood.

The crater Yerkes on the Moon is named in his honor.

Yerkes and his second wife Mary were painted by his favorite artist Jan van Beers (National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.). His wife, the daughter of Thomas Moore of Philadelphia, was also painted in 1892 by the Swiss-born American artist Adolfo Müller-Ury (1862–1947). In 1893 Müller-Ury painted from miniatures portraits of Yerkes's Quaker grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. Silas Yerkes. A year after Yerkes's death, his widow married playwright and raconteur Wilson Mizner.

References

- The Economist (2014).

- Hall (1896).

- "Charles Tyson Yerkes - American financier". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- "Newspapers". www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. Retrieved April 19, 2021.

- "The Dream City: Invasion of Cupid's Realm ("The Wasp's Nest")". columbus.gl.iit.edu.

- Catalog nr. 13 in Yerkes art catalog (Volume II)

- The Baltimore Sun (1905).

Sources

- "Charles T. Yerkes Dead". The Baltimore Sun. New York. December 30, 1905. p. 2. Retrieved December 9, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Conquistador of Metroland". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. December 20, 2014. Retrieved January 7, 2016.

- Franch, John (2008). Robber Baron: The Life of Charles Tyson Yerkes. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252075179. OCLC 62679786.

- Hall, Henry, ed. (1896). America's Successful Men of Affairs: An Encyclopedia of Contemporaneous Biography. Vol. II. The New York Tribune Company. pp. 901–904. Retrieved December 9, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- Harlan, Homer Charles (1975). Charles Tyson Yerkes and the Chicago Transportation System. University of Chicago, Department of History. OCLC 31237397.

- Sherwood, Tim (2009). Charles Tyson Yerkes: Railway Tycoon. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752446226. OCLC 191810493.