Princess Charlotte of Prussia

Princess Charlotte of Prussia (German: Victoria Elisabeth Augusta Charlotte Prinzessin von Preußen; 24 July 1860 – 1 October 1919) was Duchess of Saxe-Meiningen from 1914 to 1918 as the wife of Bernhard III, the duchy's last ruler. Born at the Neues Palais in Potsdam, she was the second child and eldest daughter of Prince Frederick of Prussia, a member of the House of Hohenzollern who became Crown Prince of Prussia in 1861 and German Emperor in 1888. Through her mother Victoria, Princess Royal, Charlotte was the eldest granddaughter of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.

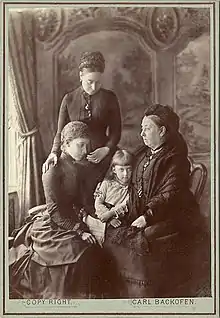

| Charlotte of Prussia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Photograph, c. 1878 | |||||

| Duchess consort of Saxe-Meiningen | |||||

| Tenure | 25 June 1914 – 10 November 1918 | ||||

| Born | 24 July 1860 New Palace, Potsdam, Kingdom of Prussia | ||||

| Died | 1 October 1919 (aged 59) Baden-Baden, Weimar Republic | ||||

| Burial | 7 October 1919 Schloss Altenstein, Thuringia, Germany | ||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | Princess Feodora | ||||

| |||||

| House | Hohenzollern | ||||

| Father | Frederick III, German Emperor | ||||

| Mother | Victoria, Princess Royal | ||||

| Prussian Royalty |

| House of Hohenzollern |

|---|

|

| Frederick III |

|

Princess Charlotte was a difficult child and indifferent student, with a nervous disposition. Her relationship with her demanding mother was strained. As she grew older, Charlotte developed a penchant for spreading gossip and causing trouble. Eager to escape from parental control, at age seventeen, she married Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Meiningen in 1878. Her husband's weak-willed personality had little effect on her. Known for spreading gossip and her eccentric personality, Princess Charlotte enjoyed Berlin society while frequently leaving her only child, Princess Feodora, in the care of family members. Charlotte and Feodora, in turn, also had a difficult relationship.

Charlotte's brother succeeded their father as Emperor Wilhelm II in 1888, increasing her social influence. Throughout her brother's reign, she was known for her mischief-making, and spent her life in between bouts of illness, in frivolous and extravagant pursuits. She became Duchess of Saxe-Meiningen in 1914, only for her husband to lose his title with the end of World War I in 1918. Charlotte died the following year of a heart attack in Baden-Baden. She had suffered from a lifetime of ill health. Recent historians have argued that she had porphyria, a genetic disease that afflicted the British royal family.

Early life

Birth and family

Princess Viktoria Elisabeth Auguste Charlotte was born on 24 July 1860 at the Neues Palais in Potsdam. She was the eldest daughter and second child of Prince Frederick William of Prussia and his wife Victoria, Princess Royal, known as Vicky in the family.[1][2] The product of an easy labour, she was a healthy baby who arrived 19 months after the difficult birth of her elder brother, Prince Wilhelm.[1][3][4] Her grandmother, Queen Victoria, wanted her eldest granddaughter to be named after her. However, the Prussians wanted the new princess to be named Charlotte after Empress Alexandra Feodorovna of Russia, who had been born Princess Charlotte of Prussia. As a compromise, her first name was Victoria, but she was always referred as Charlotte. She was also named after her paternal grandmother, Queen Augusta of Prussia. [3]

Charlotte's paternal family belonged to the House of Hohenzollern, a royal house that had ruled the German state of Prussia since the seventeenth century.[5] By the end of her first year, Charlotte's father had become Crown Prince as his father ascended to the Prussian throne as King Wilhelm I. Charlotte's mother, Vicky, was the eldest daughter of the British monarch Queen Victoria and her husband Albert, Prince Consort.[3] Charlotte and her brother, Wilhelm, were the only grandchildren born in Albert's lifetime.[6] He and Victoria visited their daughter and two grandchildren when Charlotte was two months old;[7][8] Vicky and Frederick William in turn brought Wilhelm and Charlotte on a visit to England in June 1861,[9] six months before Albert's death.[10]

Upbringing and education

The growing family, which came to include eight children,[11] spent its winters in Berlin and summers in Potsdam; the year also usually included a stay in the country, to the delight of the children. In 1863, Vicky and Frederick William purchased a run-down property and refurbished it into a farm, allowing the family to periodically experience a simple country life.[12] Frederick William was a loving husband, but as an officer in the Prussian army, his duties increasingly pulled him away from the home. Vicky was an intellectually demanding mother who expected her children to exhibit moral and political leadership, and in her husband's absence she carefully supervised their education and upbringing.[13] Shortly after arriving in her new adopted country, Vicky observed the continuous arguments and intrigues within the Prussian royal family. This bolstered her belief in the superiority of English culture; she raised her children in English-style nurseries, and successfully fostered a love of her native country by incorporating aspects of English culture in the home and taking them on frequent trips to England.[14]

While Vicky was close with her eldest daughter, this changed as the girl grew older; by the time she was two years old, Charlotte had become known as "sweet naughty little Ditta"[15] and would prove to be the most difficult of the family's eight children.[15][16] As a young girl, she acted nervously and made frequent displays of agitation, such as pulling at her clothes. An early habit of biting her nails led to preventative measures like the forced wearing of gloves, but any methods only provided temporary relief.[16][17] Queen Victoria wrote to her daughter, "tell Charlotte I was appalled to hear of her biting her things. Grandmamma does not like naughty little girls".[16] In 1863 the Crown Princess recorded in her diary that Charlotte's "little mind seems almost too active for her body – she is so nervous & sensitive and so quick. Her sleep is not so sound as it should be – and she is so very thin."[15] Charlotte developed violent tantrums; Vicky described them as "such outbreaks of rage & stubbornness that she screams blue murder."[18] The young girl was also underweight and had a troublesome digestion.[19]

Charlotte was an indifferent student, to the dismay of her mother, who placed a high value on education. Charlotte's governess declared she had never seen "more difficulties" than with the princess, while Vicky once wrote of Charlotte in a letter to her mother that "Stupidity is not a sin, but it renders education a hard and difficult task."[16][20] The Crown Princess rarely withheld her true thoughts of those who displeased her,[21] and bluntly admonished her children to encourage their efforts and help them avoid vanity.[8] Queen Victoria urged her daughter to act encouragingly rather than reproachfully towards Charlotte, believing that she could not expect the young princess to share Vicky's tastes.[17] The biographer Jerrold M. Packard thinks it likely that the "pretty but nervous and sullen girl sensed [her mother's] disappointment from an early age," exacerbating the gulf between them.[21]

Over time, a rift developed between the family's three eldest and three youngest children.[22][23] The deaths of Charlotte's brothers Sigismund and Waldemar in 1866 and 1879, respectively, devastated the Crown Princess. The historian John C. G. Röhl posits that Vicky's eldest three children "could never live up to [her] idealised memory of the two dead princes."[24] The strict upbringing Vicky gave to the eldest three children—Wilhelm, Charlotte, and Henry—was not replicated in her relationship with her three youngest surviving children, Viktoria, Sophia, and Margaret.[23][25] The eldest children, in turn and sensing their mother's disappointment, became resentful of Vicky's indulgence towards their youngest siblings.[8] The historian John Van der Kiste speculates that had Vicky shown the same level of acceptance with Charlotte as with her younger children, "the relationship between them might have been a happier one".[23]

Charlotte was a favourite of her paternal grandparents,[16] whom she frequently saw.[26] King Wilhelm and Queen Augusta spoiled their granddaughter and encouraged her rebellion against the Crown Prince and Princess,[27] and Charlotte and her brother frequently took their side in disputes with her parents.[28] This rebellion was encouraged by the German chancellor Otto von Bismarck, who held political disagreements with the liberal Crown Prince and Princess.[11] Charlotte also enjoyed a close relationship with her eldest brother,[3] though they grew apart after his marriage in 1881 to Augusta Victoria of Schleswig-Holstein ("Dona"), a princess described by Charlotte as plain, slow-witted, and shy.[3][29] Charlotte's relationship with Wilhelm would remain troubled as a result.[27] Charlotte's cousin, Queen Marie of Romania, wrote in her memoirs: "it was greatly owing to Charly's intrigues that King Carol's animosity against the Emperor Wilhelm was kept alive. Charly had a grudge against her brother and was glad to do him a bad turn whenever she could."[30]

Engagement and marriage

By the time she reached fourteen, Charlotte was described by Vicky as appearing much younger than her age; Vicky wrote, "Charlotte is in everything – health, looks and understanding, like a child of ten!"[31] The princess had short legs, which, paired with a long waist and arms, made her appear tall when sitting but short when standing. She was also quite plain.[32] She suffered from significant health issues for the majority of her adult life; this was accompanied by a nearly continuous state of mental agitation and wild excitement, confusing her doctors.[29] Her many health issues included rheumatism, joint pains, headaches and insomnia.[33]

As Charlotte grew older, her behaviour came to include flirtation, spreading malicious gossip, and causing trouble, traits her mother had noticed in her daughter's youth and had hoped she would outgrow.[34] Vicky characterised her as a "wheedling little kitten [who] can be so loving whenever she wants something".[18] She believed that Charlotte's "pretty exterior" hid "dangerous character traits," and blamed nature for producing such qualities in her daughter.[35][18]

In April 1877, the sixteen-year-old Charlotte became engaged to her second cousin Prince Bernhard of Saxe-Meiningen, heir to the German Duchy of Saxe-Meiningen.[36] According to a story related by Vicky's biographer, Hannah Pakula, Charlotte fell in love with the prince while they were driving with her eldest brother; Wilhelm sped up during the drive, alarming Charlotte and causing her to cling to Bernhard's arm. Pakula adds that this sudden but temporary passion likely fit Charlotte's "changeable" personality.[37] Van der Kiste believes Charlotte's decision to marry Bernhard also stemmed from a desire to become independent of her parents, and especially from her mother's criticism.[35]

Prince Bernhard, an army officer serving in a Potsdam regiment,[37] was nine years her senior and a veteran of the recent Franco-Prussian War. Though regarded as weak-willed,[35] he had many intellectual interests, particularly in archaeology.[27] Charlotte did not share these interests,[37] but Vicky hoped that time as well as marriage would guide Charlotte, so that "at least her wicked qualities will not be able to cause any harm".[18] The engagement lasted nearly a year, with Vicky preparing her daughter's trousseau.[38] They were married in Berlin on 18 February 1878, in a double ceremony that also included Princess Elisabeth Anna of Prussia's marriage to Frederick Augustus of Oldenburg.[39] Charlotte's maternal uncles, the Prince of Wales and Duke of Connaught and Strathearn, attended the wedding, as did King Leopold II and Queen Marie Henriette of the Belgians.[40][41]

The new couple established their household near the Neues Palais, in a small villa previously inhabited by Auguste von Harrach, the morganatic wife of Frederick William III of Prussia.[42] They also purchased a villa in Cannes, a decision that angered Wilhelm, who viewed France as an enemy country; Charlotte eventually spent most of her winters in the French city, as she hoped that its warm climate would help alleviate her lifetime of ill health.[43][44]

Birth of Princess Feodora

One year into their marriage, Charlotte gave birth to a daughter, Princess Feodora, on 12 May 1879. The new princess was the first grandchild of the Crown Prince and Princess, as well as the first great-grandchild of Queen Victoria.[45][46] Charlotte had hated the limitations placed on her while pregnant, and decided this would be her only child, to the dismay of her mother. Following Feodora's birth, Charlotte devoted her time to enjoying society life in Berlin[47][46] and embarking on long holiday trips. During these trips, Charlotte would often leave her daughter to stay with Vicky, whom she viewed as the source of a convenient nursery.[48] Feodora frequently made long visits to Friedrichshof, her maternal grandmother's estate.[49] On one occasion, Vicky observed that Feodora "is really a good little child and far easier to manage than her mother."[50]

Among the era's royal families, it was unusual to be an only child; Feodora likely endured a lonely childhood.[49] Like her mother, Feodora suffered from sickness and various physical pains, as well as severe migraines.[51] Feodora also lacked an interest in her studies, a deficit blamed by Vicky on a lack of parental guidance, as Charlotte and Bernhard were frequently away. Vicky commented, "The atmosphere of her home is not the best for a child of her age... With Charlotte for an example, what else can one expect."[50]

Adulthood

Wilhelm I granted Charlotte and Bernhard a villa near Tiergarten in Berlin and transferred Bernhard to a regiment in the city. Charlotte spent much of her time socialising with other ladies, where it was common to pursue activities such as skating, gossiping, and holding dinner parties. She was admired for her fashion sense, having imported all of her clothing from Paris. Charlotte also smoked and drank, and was liked by many for hosting entertaining parties. She earned a reputation as a gossip, and many found her acid-tongued. She was known for befriending someone and earning their confidence, only to spread their secrets to others.[52]

Charlotte's father ascended the German throne as Emperor Frederick III in March 1888,[53] only to succumb to throat cancer in June of that year. Charlotte stayed with her ailing father during this period, alongside most of her siblings.[54] With her brother's ascension as Wilhelm II, Charlotte's social influence increased in Berlin, where she surrounded herself with a wild group of nobles, diplomats, and young officials from the court.[55] While she had gradually reconciled with her mother during Frederick's illness, Charlotte sided with Wilhelm when he complained that he should have attended Queen Victoria's Golden Jubilee in place of his ailing father.[56] Upon Wilhelm's ascension, Charlotte and Bernhard took his side in disputes with Vicky; the Dowager Empress, in turn, was defended by her three youngest daughters. In one letter during this period, Vicky characterised her eldest daughter as "most odd" and "hardly com[ing] near me, also describing Bernhard as impertinent and rude.[57]

Letters scandal

In early 1891,[58] Berlin society erupted in scandal after a series of anonymous letters circulated to prominent members of the court, including Wilhelm and his wife Dona. The letters were written in the same handwriting, and featured salacious gossip, accusations, and intrigues among the court's powerful. Some included pornographic images layered upon royal photographs.[59] Several hundred letters were sent over a four-year period.[58] Wilhelm ordered an investigation, but the writer (or writers) were never identified. Some contemporaries speculated that Charlotte, known for her sharp tongue and love of gossip, may have been responsible.[59][60] Historians have since suggested that the writer may have been Dona's brother Duke Ernst Gunther of Schleswig-Holstein in collaboration with his mistress.[61] It is clear that the author had an intimate understanding of the many personalities within the royal family, likely making him or her either a family member or courtier.[59]

During the letters scandal, Charlotte lost her diary which contained both family secrets and critical thoughts on various members of her family; the diary was eventually given to Wilhelm, who never forgave her for its contents. Bernhard was transferred to a regiment in the quiet town of Breslau, effectively exiling him and his wife. As controller of Charlotte's allowance, Wilhelm also limited their ability to travel outside of the country unless they were willing to go without royal honours.[62] In 1896, Dona accused Charlotte of engaging in an affair with Karl-August Freiherr Roeder von Diersburg, a court official. Charlotte fiercely denied the allegations. Bernhard defended his wife and criticised the Hohenzollerns for attempting to keep every Prussian princess under the control of the family. Bernhard considered resigning his army position and leaving with his wife for Meiningen, though the dispute eventually resolved itself when von Diersburg returned to court with his wife.[63] The scandal was considered to have seriously damaged the reputation of the monarchy.[64]

Relations with Feodora

As Feodora grew older, various suitors were considered for marriage. The exiled Prince Peter Karađorđević, thirty-six years her senior, unsuccessfully requested her hand in marriage. Another potential candidate was her cousin Alfred, Hereditary Prince of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.[65] In late 1897, Feodora became engaged to Prince Henry XXX of Reuss, and they married the following year, on 24 September 1898 in a Lutheran ceremony at Breslau. The groom was fifteen years older than his bride and a captain in a Brunswick regiment, but not wealthy or particularly high-ranked. Many in the family were shocked at the marriage, but the Dowager Empress was at least pleased that her granddaughter seemed happy with the match.[66]

As her husband acquired military assignments, Feodora travelled throughout Germany.[67] The marriage, however, did not improve relations between mother and daughter. After a visit by the couple in 1899, Charlotte wrote that Feodora was "incomprehensible" and "shrinks away, whenever I try to influence her, concerning her person & health".[68] Charlotte also disliked her son-in-law, criticizing his appearance and inability to control his strong-willed wife. Unlike her mother, Feodora wanted children; her inability to conceive left Feodora disappointed, though it pleased Charlotte, who had no desire for grandchildren.[69]

Van der Kiste writes that Charlotte and Feodora had very similar personalities, "both strong-willed creatures who loved gossip and were too ready to believe the worst of each other".[70] Eventually, their relationship deteriorated enough for Charlotte to bar Feodora and Henry from her house. Charlotte refused to accept Feodora's claim to have malaria, believing instead that her daughter had contracted a venereal disease from Henry; this opinion outraged Feodora.[70] Over the years members of the family tried to repair the mother-daughter relationship, without success. Charlotte did not write to Feodora for nearly a decade, finally doing so after Feodora underwent a dangerous operation to help her conceive. Charlotte expressed outrage that such an operation had been approved, but eventually visited her in the sanatorium at Feodora's request.[71]

Duchess of Saxe-Meiningen; death

In June 1911, Charlotte attended her cousin George V's coronation in England, but the country's summer heat left her bed-ridden with a swollen face and pain in her limbs.[44] On 25 June 1914, her husband inherited his father's duchy and became Bernhard III, Duke of Saxe-Meiningen. World War I broke out on 28 July; Bernhard left for the front while Charlotte remained behind to oversee the duchy, serving mainly as a figurehead (German: Landesregentin). During the war, Charlotte increasingly experienced various pains including chronic aches, swollen legs, and kidney problems.[72] The degree of the pain became so severe that she took opium as her only comfortable treatment.[67]

The end of the war in 1918 led to the political demise of the German Empire, as well as all of its many duchies; consequently, Bernhard was forced to abdicate his rule over Saxe-Meiningen. The following year, Charlotte travelled to Baden-Baden to seek medical treatment for her heart, ultimately dying there of a heart attack on 1 October 1919 at the age of 59. Bernhard died nine years later and was buried with her at Schloss Altenstein in Thuringia.[73]

Medical analysis

Recent historians have argued that Charlotte and Feodora were afflicted with porphyria, a genetic disease that is believed to have affected some members of the British Royal Family, most notably King George III.[29][74] In their 1998 book Purple Secret: Genes, 'Madness', and the Royal Houses of Europe, the historian John C. G. Röhl and the geneticists Martin Warren and David Hunt identify Charlotte as "occup[ying] a crucial position in [the] search for the porphyria mutation in the descendants of the Hanoverians".[75]

For evidence, Röhl reviewed letters between Charlotte and her doctor, as well as correspondence with her parents, that had been sent over a 25-year period; he found that even as a little girl, Charlotte had suffered from hyperactivity and indigestion.[76] As a young woman, Charlotte became gravely ill with what her mother called "malaria poisoning and anaemia," followed by "neuralgia, fainting and nausea," all described by Röhl as a "textbook list of the symptoms of porphyria, and this several decades before the disorder was clinically identified".[77] Röhl also notes further symptoms described in letters between Charlotte and her physician Ernst Schweningerwho treated her for over two decades beginning in the early 1890s.[75] In them, Charlotte variously complains of "toothache, backache, insomnia, dizzy spells, nausea, constipation, excruciating 'wandering' abdominal pains, skin oedema and itching, partial paralysis of the legs and dark red or orange urine," the last of which Röhl calls the "decisive diagnostic symptom."[77]

In the 1990s, a team led by Röhl exhumed Charlotte's and Feodora's graves and took samples of each princess for testing. In both mother and daughter, the researchers found evidence of a mutation related to porphyria. While the team noted they could not be completely certain that this mutation was caused by the genetic disease,[78] and believed it beyond dispute, based on the historical and biological evidence,[79] they noted that many of the same symptoms were found in Charlotte's mother, Vicky, as well as other family members including Queen Victoria. Röhl, Warren, and Hunt conclude "...for what else could have caused their terrible attacks of lameness and abdominal pain and skin rashes– and in Charlotte's case dark red urine?"[79]

Honours

- Companion of the Order of the Crown of India, 19 June 1911[80]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Princess Charlotte of Prussia |

|---|

References

- Pakula 1997, p. 138.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 33.

- Van der Kiste 1999.

- Packard 1998, p. 106.

- Pakula 1997, pp. 94–101.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 47.

- Hibbert 2001, p. 261.

- Van der Kiste 2001.

- Röhl 1998, p. 73.

- Pakula 1997, pp. 153–59.

- Ramm 2004.

- Pakula 1997, p. 323.

- Pakula 1997, pp. 321–24.

- Gelardi 2005, pp. 9–11.

- Röhl 1998, p. 106.

- Pakula 1997, p. 335.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 87.

- Röhl 1998, p. 107.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, pp. 183–84.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, p. 183.

- Packard 1998, p. 135.

- Röhl 1998, p. 101.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 60.

- Röhl 2014, p. 13.

- MacDonogh 2000, p. 36.

- King 2007, p. 50.

- Van der Kiste 2012.

- Packard 1998, p. 173.

- Vovk 2012, p. 41.

- Marie, Queen (1934). The story of my life [by] Marie, queen of Romania. State Library of Pennsylvania. C. Scribner’s sons. p. 345.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, p. 184.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, pp. 184–84.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 601.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, p. 185.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 126.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 113.

- Pakula 1997, p. 371.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 138.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 141.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 141–154.

- MacDonogh 2000, p. 60.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 180.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 559.

- Rushton 2008, p. 117.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 192.

- Pakula 1997, p. 374.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 207.

- Packard 1998, p. 292.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 458.

- Pakula 1997, p. 561.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 601–614.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 207–220.

- Pakula 1997, pp. 461–62.

- Packard 1998, p. 258.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, p. 187.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 259.

- Röhl 2004, p. 633.

- Röhl 2004, p. 664.

- Van der Kiste 1999, p. 91.

- Röhl 2004, p. 676.

- Röhl 2004, pp. 672–73.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 259–404.

- Röhl 2004, p. 638.

- Röhl, John C. G. Wilhelm II: The Kaiser's Personal Monarchy, 1888–1900, Cambridge University Press, 2004. p676

- Van der Kiste 2012, 486–499.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 499.

- Rushton 2008, p. 118.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 585.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 571, 654.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 654.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 654–669, 699–740.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 785–838.

- Van der Kiste 2012, 851–864.

- Röhl 2014, p. 9.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, p. 182.

- Röhl 1998, pp. 105–08.

- Röhl 1998, p. 109.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, pp. 259–69.

- Röhl, Warren & Hunt 1998, p. 310.

- "No. 12366". The Edinburgh Gazette. 23 June 1911. p. 625.

- Works cited

- Gelardi, Julia P. (2005). Born to Rule: Five Reigning Consorts, Granddaughters of Queen Victoria. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-32423-5.

- Hibbert, Christopher (2001). Queen Victoria: A Personal History. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81085-9.

- King, Greg (2007). Twilight of Splendor: The Court of Queen Victoria During Her Diamond Jubilee Year. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-04439-1.

- MacDonogh, Giles (2000). The Last Kaiser: The Life of Wilhelm II. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-30557-5.

- Packard, Jerome M. (1998). Victoria's Daughters. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0312244967.

- Pakula, Hannah (1997). An Uncommon Woman: The Empress Frederick, Daughter of Queen Victoria, Wife of the Crown Prince of Prussia, Mother of Kaiser Wilhelm. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 0684842165.

- Ramm, Agatha (2004). "Victoria, Princess Royal (1840–1901)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/36653. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Röhl, John C.G.; Warren, Martin; Hunt, David (1998). Purple Secret: Genes, 'Madness', and the Royal Houses of Europe. Bantam Press. ISBN 0593041488.

- Röhl, John C.G. (1998). Young Wilhelm: The Kaiser's Early Life, 1859–1888. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521497523.

- Röhl, John C.G. (2004). Wilhelm II: The Kaiser's Personal Monarchy, 1888–1900. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521819206.

- Röhl, John C.G. (2014). Kaiser Wilhelm II: A Concise Life. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107072251.

- Rushton, Alan R. (2008). Royal Maladies: Inherited Diseases in the Ruling Houses of Europe. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 978-1425168100.

- Van der Kiste, John (1999). Kaiser Wilhelm II: Germany's Last Emperor. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752499284.

- Van der Kiste, John (2001). Dearest Vicky, Darling Fritz: Queen Victoria's Eldest Daughter and the German Emperor. Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-750-93052-7.

- Van der Kiste, John (2012). Charlotte and Feodora: A Troubled Mother-Daughter Relationship in Imperial Germany (Kindle ed.). ASIN B0136DZ71E.

- Vovk, Justin C. (2012). Imperial Requiem: Four Royal Women and the Fall of the Age of Empires. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4759-1749-9.

Further reading

- Blankart, Michaela (2013). "Charlotte Prinzessin von Preussen". Preussen.de (in German). House of Hohenzollern. Archived from the original on 12 October 2017. Retrieved 11 January 2016.

- Van der Kiste, John (2015). Prussian Princesses: The Sisters of Kaiser Wilhelm II. Fonthill Media. ISBN 978-1781554357.