1987 Maryland train collision

On January 4, 1987, two trains collided on Amtrak's Northeast Corridor main line near Chase, Maryland, United States, at Gunpow Interlocking. Amtrak train 94, the Colonial, (now part of the Northeast Regional) traveling north from Washington, D.C., to Boston, crashed at over 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) into a set of Conrail locomotives running light (without freight cars) which had fouled (entered) the mainline. Fourteen passengers on the Amtrak train died, as well as the Amtrak engineer and lounge car attendant.[1]

| 1987 Maryland train collision | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

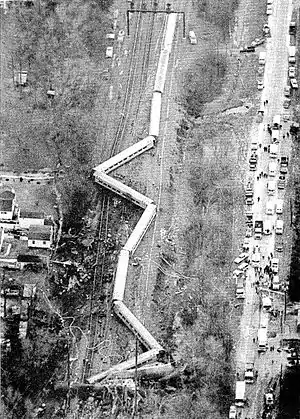

Aerial view of the Colonial after the accident | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date | January 4, 1987 1:30 PM | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Chase, Maryland, United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 39°22′35″N 76°21′25″W | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Country | United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Line | Northeast Corridor | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Amtrak Conrail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Incident type | Collision | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cause | Engineer error, Noncompliance with stop Signal preventable by ATP/ATC and other safety measures | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Trains | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Passengers | 660 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deaths | 16 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Injured | 164 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Conrail locomotive crew failed to stop at the signals before Gunpow Interlocking, and it was determined that the accident would have been avoided had they done so. Additionally, they tested positive for cannabis.[1] The engineer served four years in a Maryland prison for his role in the crash. In the aftermath, drug and alcohol procedures for train crews were overhauled by the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA), which is charged with rail safety. In 1991, prompted in large part by this crash, the United States Congress took even broader action and authorized mandatory random drug-testing for all employees in "safety-sensitive" jobs in all industries regulated by the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) including trucking, bus carriers and rail systems. Additionally, all trains operating on the high-speed Northeast Corridor are now equipped with automatic cab signalling with an automatic train stop feature. Several safety issues were identified with Amfleet cars as well.[2]

At the time, the wreck was the deadliest in Amtrak's history. It was surpassed in 1993 by the Big Bayou Canot rail accident in Alabama where 47 died and another 103 were injured.[3]

Movements of the trains pre-collision

Amtrak Train 94

Amtrak Train 94 (the Colonial) left Washington Union Station at 12:30 pm (Eastern time) for Boston South Station. The train had 12 cars and was filled with travelers returning from the holiday season to their homes and schools for the second semester of the year. Two AEM-7 locomotives, numbered 900 and 903, led the train; #903 was the lead locomotive. The engineer was 35-year-old Jerome Evans.[1]

After leaving Baltimore Penn Station, the train's next stop was Wilmington, Delaware. Just north of Baltimore, while still in Baltimore County, the four-track Northeast Corridor narrows to two tracks at Gunpow Interlocking just before crossing over the Gunpowder River. The train accelerated north toward that location.[1]

Conrail light engine move

Ricky Lynn Gates, a Penn Central and Conrail engineer since 1973, was operating a trio of Conrail GE B36-7 locomotives light (with no freight cars) from Conrail's Bayview Yard just east of Baltimore bound for Enola Yard near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. Gates was later determined to have violated several signal and operating rules, including a failure to properly test his cab signals as required before departure from Bayview. It was later discovered that someone had disabled the cab signal alerter whistle on lead unit #5044 with duct tape, muting it almost completely. Also, one of the light bulbs in the PRR-style cab signal display had been removed. Investigators believed these conditions probably existed prior to departure from Bayview and that they would have been revealed by a properly performed departure test.[1]

Gates and his brakeman, Edward "Butch" Cromwell, were also smoking cannabis cigarettes.[4] Cannabis can alter one's sense of time and impair the ability to perform tasks that require concentration.[5] Cromwell was responsible for calling out the signals if Gates missed them, but failed to do so.[1]

The collision

Amtrak train #94 was north-bound on track #2 of the electrified main line leading to Gunpow Interlocking. As Amtrak was approaching the interlocking, a “light” Conrail consist of three diesel-electric freight locomotives was running north-bound on parallel track #1 in a ferrying move (see photo to right for track identification). Gunpow Interlocking is fully signaled to govern train movements, with all signals mounted on signal bridges straddling the tracks, placing them in clear view of oncoming trains.[1]

Shortly before reaching the Gunpowder River bridge, track #1 merges left into track #2 through a number 20 turnout that is controlled by the interlocking. Home signals govern the approach legs of the turnout, with their most restrictive aspect being STOP. Unlike some interlocking arrangements, Gunpow had no provisions for derailing and stopping a car or locomotive that is about to foul a turnout that is aligned against it.[1]

At the time, track #1 was limited to a maximum speed of 80 miles per hour (130 km/h) for passenger trains, and a maximum of 50 miles per hour (80 km/h) for freight. As the Conrail freight consist was running light, it was authorized to travel at up to 60 miles per hour (97 km/h). On the other hand, passenger train speeds as high as 125 miles per hour (201 km/h) were permitted on track #2.[1]

NTSB investigators determined that immediately prior to the collision, the interlocking had been properly configured for through movement on track #2.[1] It was also determined the distant and home signals governing the track #2 approach to the interlocking were both indicating CLEAR, thus permitting Amtrak #94 to proceed through the interlocking at maximum authorized speed. At the same time, the distant and home signals governing track #1 leading to the interlocking were determined to be indicating APPROACH and STOP, respectively, thus requiring that Conrail reduce speed and come to a full stop before reaching the home signal.

Furthermore, it was found that the in-cab signal in the Conrail lead locomotive indicated the STOP aspect being displayed by the home signal as it was approached, but could not indicate an APPROACH aspect, due to the APPROACH indicator lamp not being present in the in-cab signal’s housing.[1] The in-cab signal’s alerter whistle, which would have audibly warned the engineer that the signal aspect had become more restrictive, was found to have been muffled by being wrapped with duct tape.[1] NSTB investigators determined that the whistle was not audible over the noises emitted by the locomotive, even when idling.[1] None of the three Conrail locomotives was equipped with an automatic train stop feature that would have involuntarily cut power and applied the brakes (a so-called “penalty” brake application) should the engineer not acknowledge the in-cab signal when it changed to a more restrictive aspect.

Event recording devices on the Conrail locomotives indicated that the consist was moving at approximately 60 miles per hour (97 km/h) when an emergency brake application was made by engineer Gates. The brake application occurred after passing the distant signal, which as previously noted, was indicating APPROACH, requiring an immediate speed reduction. Gates later claimed he made the brake application when he realized that he didn’t have authorization to proceed through the interlocking. At that point, his consist was moving too fast to stop before passing the home signal. Examination of the interlocking system's computerized event recorder revealed that the Conrail consist forced its way through the turnout and onto track #2 approximately 15 seconds before the collision. Had Gates obeyed the signals—also, had brakeman Cromwell, riding in the cab with Gates, called out the signals as he was required to do, it is likely the Conrail consist could have been stopped before running past the home signal.[1]

Upon entering track #2, the Conrail locomotives caused the interlocking home signal for that track to immediately change to a STOP aspect, after which they came to a halt. At that time, Amtrak #94 was approximately 3,000 ft (910 m) from the stopped Conrail units. With his train approaching Gunpow at more than 120 mph (190 km/h),[1] engineer Evans had little time to react to the sudden signal change and the presence of the Conrail locomotives in his path. However, he managed to initiate an emergency brake application seconds before the impact occurred at 1:30 pm.

At the point of impact, Amtrak #94 had decelerated to 107 mph (172 km/h) (speed determined from the locomotives’ event recorders). The Conrail consist was stationary with its brakes applied. On impact, the fuel tank of the trailing Conrail locomotive, GE B36-7 #5045, was ruptured, dumping a large quantity of fuel, which ignited and resulted in the locomotive being burned to the frame—the unit was subsequently scrapped. The middle unit, #5052, sustained significant damage to its front end, while lead unit #5044 suffered only minor damage. The force of the impact was so severe unit #5044 was driven forward some 900 feet from the point where the consist had stopped.[1]

Amtrak’s lead locomotive, AEM-7 #903, ended up among some trees on the west side of the right-of-way, with the forward cab crushed. AEM-7 #900, which was the trailing unit, was buried under wreckage. Both locomotives were completely demolished. Cars were jackknifed and piled up on each other, with some cars crushed.[1]

Brakeman Cromwell, who was on the lead Conrail locomotive, suffered a broken leg in the collision. Engineer Gates was uninjured. Amtrak engineer Evans, the lounge car’s Lead Service Attendant and 14 passengers died. Many surviving passengers were injured by flying objects hurled from the luggage racks.[1] The front cars on Amtrak #94 suffered the greatest amount of damage and were almost completely crushed. However, those cars were nearly empty, awaiting passengers who would have boarded the train at stations further north. According to the NTSB, had these cars been fully occupied at the time, the death toll would have been at least 100. There were relatively few passengers on those cars, however, and so the death toll was much less. Most of the fatalities were on Amtrak car #21236.[1]

Although track #2 was rated for 125 mph (201 km/h) passenger service, it was noted that the Amtrak train was being operated at an excessive speed due to the presence of a Heritage-style coach in the consist, Heritage cars being limited to 105 mph (169 km/h) maximum.[1] Train #94’s conductor later testified that he did inform the Amtrak engineer of the Heritage car being in the train. However, it was subsequently learned the Amtrak dispatcher responsible for #94 did not know there was a restricted-speed car in the train. NTSB investigators later concluded the Amtrak train’s speed wasn’t a significant factor in the events leading to the wreck.[1]

Post-collision response and cleanup

With a total passenger load of about 600 people, there was a great deal of confusion after the collision. Witnesses and neighbors ran to the smoking train and helped remove injured and dazed passengers, even before the first emergency vehicles could arrive at the location.

While many of the injured passengers were aided by nearby residents, some of the uninjured passengers wandered away, making it difficult for Amtrak to know the complete story.

Emergency personnel worked for many hours in the frigid cold to extricate trapped passengers from the wreckage, impeded by the stainless-steel Amfleet cars' skin resistance to ordinary hydraulic rescue tools. Helicopters and ambulances transported injured people to hospitals and trauma centers. It was over 10 hours after the collision before the final trapped people were freed from the wreckage.[1]

It was several days before the wrecked equipment was removed and the track and electrical propulsion system were returned to service.

Conrail diesel, GE B36-7 #5045 was completely destroyed while #5044 and #5052 were repaired and returned to service. Both Amtrak's AEM-7s and a few Amfleet cars were also destroyed in the collision.[1]

Investigation, charges and conviction

.jpg.webp)

Gates and Cromwell initially denied smoking cannabis. However, they later tested positive for the substance. A National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) investigation revealed that had Gates slowed down at the signals as required, he would have stopped in time. It also determined that Gates and Cromwell's cannabis use was the "probable cause" of the accident.[4] Gates and Cromwell were immediately suspended by Conrail pending an internal investigation, but resigned rather than face certain termination.

Gates was eventually charged with manslaughter by locomotive; under Maryland law a locomotive is considered a motor vehicle. Prosecutors cut a deal with Cromwell in which he agreed to testify against Gates in return for immunity. Gates was sentenced to five years in state prison and one year's probation, and was later sentenced to an additional three years on federal charges of lying to the NTSB. Gates' history of DWI (driving while intoxicated) convictions as well as his admission that the crew had been using cannabis while on duty led for a call to certify locomotive engineers as to their qualifications and history.[4]

Toxicology tests on the Amtrak engineer's body returned negative. In a 3-2 decision, the NTSB report stated that the speed of train #94 at the time the brakes were applied, between 120 and 125 mph (193 and 201 km/h), was an unauthorized excessive speed, since the maximum for an Amtrak train carrying Heritage cars was 105 mph (169 km/h). The excessive speed was determined to have been a contributing factor to the amount of damage to both trains at the point of impact. The two dissenters to the report believed that it was unreasonable to assign contributory blame to the Amtrak engineer based solely on the premise of the Heritage car lowering its speed limit.[1]

Gates was released from prison in 1992 after serving four years (two years of a state sentence, then two more years of a federal sentence), and then worked as an abuse counselor at a treatment center. In a 1993 interview with The Baltimore Sun, Gates said the accident would have never happened if not for the cannabis, saying that it had thrown off his "perception of speed and distance and time." He admitted that in his rush to get back to Baltimore and get high, he skipped critical safety checks; he believed that had he performed those checks, "I wouldn't have been in front of that train." He also revealed he had smoked cannabis on the job several times.[4]

Additionally, it was never determined whether the alerter whistle was muted while the locomotives were at Bayview yard. The alerter whistle on these locomotives were notorious for being irritating and loud, which was pointed out in a 1979 accident of a Union Pacific train in Wyoming which involved muting the whistle with a rag. The whistle was easily accessible by removing a cover on the back of the control stand that was sealed with latches, so it was possible for the Conrail crew to have muted the whistle before they left or before the units arrived at Bayview yard (which would have been done by other crews), but Gates reported that the whistle was relatively faint when it was tested, which meant that it could not be heard over the sound of the trailing units. The whistle was so well muted, that when it was sent to the FBI, they were not able to determine when and who muted it, due to the lack of fingerprints.

When Conrail unit 5044 was tested after the accident, it was found that all light bulbs (including a replacement for the missing one) were working, and it was undetermined whether the light bulb was removed while Conrail and Amtrak left the units unattended. Gates recalled having tested the cab signalling and seeing all the aspects, but he might have not looked at all the lights. The deadmans pedal was also found to have been disabled, when Gates was trying to reactivate the cab signaling system by switching it off in the nose of the locomotive (this was despite the cab signalling and deadmans pedal levers being different in aspect). The data recorder found that the reverser was put into the reverse position two hours after the accident, and the locomotive's fuses, battery and engine switched off.[1]

Changes for future prevention

As a result of the wreck, all locomotives operating on the Northeast Corridor are now required to have automatic cab signaling with an automatic train stop feature.[2] Although common on passenger trains up until that time, cab signals combined with train stop and speed control had never been installed on freight locomotives due to potential train handling issues at high speed. Conrail subsequently developed a device called a locomotive speed limiter (LSL), a computerized device that is designed to monitor and control the rate of deceleration for restrictive signals in conjunction with cab signals. All freight locomotives which operate on the Northeast Corridor must now be equipped with an operating LSL which also limits top speed to 50 mph (80 km/h).[2] Previously, freight locomotives were only required to have automatic cab signals without an automatic train stop feature.

Also as a direct result of this collision, federal legislation was enacted that required the FRA to develop a system of federal certification for locomotive engineers. These regulations went into effect in January 1990. Since then, railroads are required by law to certify that their engineers are properly trained and qualified, and that they have no drug or alcohol impairment motor vehicle convictions for the five-year period prior to certification. Another effect was that age-old Rule G (The use of intoxicants or narcotics by employees subject to duty, or their possession or use while in duty, is prohibited. — UCOR, 1962) was revamped to:

Employees are prohibited from engaging in the following activities while on duty or reporting for duty:

1. Using alcoholic beverages or intoxicants, having them in their possession, or being under the influence.

2. Using or being under the influence of any drug, medication, or other controlled substance - including prescribed medication - that will in any way adversely affect their alertness, coordination, reaction, response or safety. Employees having questions about possible adverse effects of prescribed medication must consult a Company medical officer before reporting for duty.

3. Illegally possessing or selling a drug, narcotic or other controlled substance.

An employee may be required to take a breath test and/or provide a urine sample if the Company reasonably suspects violation of this rule. Refusal to comply with this requirement will be considered a violation of this rule and the employee will be promptly removed from service. Source: NORAC operating rules 6th edition effective January 1, 1997

A form of Rule G has existed in many railroad operating manuals for decades. However, the federal codification of this rule was deemed necessary to assure that any violator would be dealt with in a consistent and harsh manner. Also, anyone who passes a stop signal loses his or her FRA certification for a period not less than 30 days for a first offense. This is per 49 CFR part 240.

In 1991—prompted in large part by the Chase crash—Congress authorized mandatory random drug-testing for all employees in "safety-sensitive" jobs in industries regulated by DOT.

Memorials

Ten years after the collision, the McDonogh School of Owings Mills, Maryland, decided to build a 448-seat theater in memory of one of the crash's victims and alumna, 16-year-old Ceres Millicent Horn, daughter of American mathematicians Roger and Susan Horn. Ceres Horn graduated from McDonogh at age 15 and enrolled and was accepted at Princeton University at age 16 where she majored in astrophysics.

On January 4, 2007, the 20th anniversary of the crash, her family visited the theatre for the first time and attended a ceremony at the McDonogh School held in honor of their daughter.[6]

The Baltimore County Fire Department's medical commander at the scene 20 years earlier told the newspaper that the Amtrak crash is still being used as a case study in effective disaster response. "The reason is how the members of the professional and volunteer fire departments and the community people got together." It was, he said, "a very sad but a very proud moment" in his career.[7]

References

- "Railroad Accident Report: Rear-end Collision of Amtrak Passenger Train 94, The Colonial and Consolidated Rail Corporation Freight Train ENS-121, on the Northeast Corridor, Chase, Maryland, January 4, 1987" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. January 25, 1988. Retrieved February 10, 2018. - Copy at the USDOT ROSAP site.

- "National Transportation Safety Board Safety Recommendation" (PDF). R88-14. February 8, 1988. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- "Derailment of Amtrak Train NO. 2 on the CSXT Big Bayou Canot Bridge Accident Report". National Transportation Safety Board. September 19, 1994. Retrieved February 6, 2018.

- Roylance, Frank D. (June 16, 1993). "Ricky Gates: 6 years sober Yes, he declares, cannabis caused 1987 rail tragedy". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on July 29, 2013. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Marijuana fact sheet from George Mason University

- "January 2007 Alumni E-Newsletter" (PDF). McDonogh School. p. 2. Retrieved February 10, 2018.

- Dresser, Michael (January 4, 2007). "Responders, Residents Recall Deadly Maryland Train Crash". Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on September 20, 2008. Retrieved October 27, 2007 – via EMSresponder.com.

External links

- Picture of AEM-7 Amtrak #903 in Wilmington, Baltimore after the crash - http://www.railpictures.net/photo/78276/

- Pictures of the 2 Amtrak AEM-7's on flat cars near the accident site - Lancaster Dispatcher - Lancaster Chapter NHRS (January 2010, Vol. 41 #1) - https://web.archive.org/web/20160910044434/http://nrhs1.org/images/Dispatcher_Jan_10.pdf

Media related to 1987 Maryland train collision at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 1987 Maryland train collision at Wikimedia Commons