Chen-style tai chi

The Chen-style tai chi (Chinese: 陳氏太极拳; pinyin: Chén shì tàijíquán) is a Northern Chinese martial art and the original form of tai chi. Chen-style is characterized by silk reeling, alternating fast and slow motions, and bursts of power (fa jin).[1]

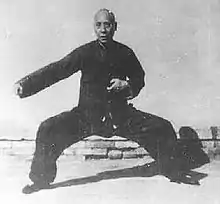

Chen-style practitioners in Single Whip | |

| Date founded | late 16th century |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | China |

| Founder | Chen Wangting |

| Current head | Chen Xiaowang 11th generation Chen |

| Arts taught | Tai chi |

| Ancestor arts | Neijia |

| Descendant arts | Yang-style tai chi, Wu (Hao)-style tai chi |

| Practitioners | Chen Fake Chen Zhaokui (陈照奎) Chen Yu (陈瑜) Chen Zhaopi (陈照丕) Chen Zhenglei Chen Xiaoxing (陈小星) Chen Boxiang (陈伯祥) |

| Part of a series on |

| Chinese martial arts (Wushu) |

|---|

|

Traditionally, tai chi is practiced as a martial art but has expanded into other domains of practice such as health or performances. Some argue that Chen-style tai chi has preserved and emphasized the martial efficacy to a greater extent.[1]

History

Origin theories

It is not clear how the Chen family actually came to practise their unique martial style and contradictory "histories" abound. What is known is that the other four tai chi styles (Yang, Sun, Wu and Wu (Hao)) trace their teachings back to Chen village in the early 1800s.[2][3]

The Chen family were originally from Hongtong County in Shanxi. In the 13th or 14th century, later documents claim that the head of the Chen family, Chen Bu (陳仆; 陈卜), migrated to Wen County, Henan. The new area was originally known as Changyang Cun (Chinese: 常陽村; lit. 'Sunshine village') and grew to include a large number of Chen descendants. Because of the three deep ravines beside the village it came to be known as Chen Jia Gou (Chinese: 陳家溝; lit. 'Chen Family Creek').[4] According to Chen Village family history, Chen Bu was a skilled martial artist who started the martial arts tradition within Chen Village. For generations onwards, the Chen Village was known for their martial arts.[5]

The special nature of tai chi practice was attributed to the ninth generation Chen Village leader, Chen Wangting.[4] He codified pre-existing Chen training practice into a corpus of seven routines. This included five routines of 108 form Long Fist (一百零八勢長拳) and a more rigorous routine known as Cannon Fist (炮捶一路). Chen Wangting integrated different elements of Chinese philosophy into the martial arts training to create a new approach that we now recognize as the Internal martial arts. These included the principles of Yin Yang, the techniques of Daoyin, Tui na, Qigong, and the theory of meridians. Those theories encountered in Classical Chinese Medicine and described in such texts as the Huangdi Neijing. In addition, Wangting incorporated the boxing theories from sixteen different martial art styles as described in the classic text, Jixiao Xinshu written by the Ming dynasty General Qi Jiguang.[5][6]

Chen Changxing, a 14th generation Chen Village martial artist, synthesized Chen Wangting's open fist training corpus into two routines that came to be known as "Old Frame" (老架; lao jia). Those two routines are named individually as the First Form (Yilu; 一路) and the Second Form (Erlu; 二路, more commonly known as the Cannon Fist 炮捶). Chen Changxing, contrary to Chen family tradition, also took the first recorded non-family member as a disciple, Yang Luchan, who went on to popularize the art throughout China, but as his own family tradition known as Yang-style tai chi. The Chen family system was only taught within the Chen village region until 1928.

Chen Youben, also of the 14th Chen generation, is credited with starting another Chen training tradition. This system also based on two routines is known as "Small Frame" (Chinese: 小架; pinyin: xiǎo jià).[5] Small Frame system of training eventually lead to the formation of two other styles of tai chi that show strong Chen family influences, Zhaobao tai chi and Hulei jia (Chinese: 忽雷架; lit. 'thunder frame'). However, these are not considered a part of the Chen family lineage.

Other origin stories

Some legends assert that a disciple of Zhang Sanfeng named Wang Zongyue taught Chen family the martial art later to be known as tai chi.[2]

Other legends speak of Jiang Fa, reputedly a monk from Wudang mountain who came to Chen village. He is said to have helped transform the Chen family art with Chen Wangting by emphasizing internal fighting practices.[7] However, there are significant difficulties with this explanation, as it is no longer clear if their relationship was that of teacher/student or even who taught whom.[2]

Recent history

During the second half of the 19th century, Yang Luchan and his family established a reputation of Yang-style tai chi throughout the Qing empire. Few people knew that Yang Luchan first learned his martial arts from Chen Changxing in the Chen Village. Fewer people still visited the Chen village to improve their understanding of tai chi. Only Wu Yuxiang, a student of Yang Luchan and the eventual founder of Wu (Hao)-style tai chi, was known to have briefly studied the Chen Family small frame system under Chen Qingping. This situation changed with the fall of the Qing empire when Chinese society sought to discover and improve their understanding of traditional philosophies and methods.

The current availability and popularity of Chen-style tai chi is reflective of the radical changes that occurred within Chinese society during the 20th century. In the decline of the Qing dynasty, the creation of the Republic of China and subsequently the Chinese Communist Revolution, Chen-style tai chi underwent a period of re-discovery, popularization, and finally internationalization.

In 1928, Chen Zhaopei (1893–1972) and later his uncle, Chen Fake moved from Chen village to teach in Beiping (now known as Beijing).[8][9] Their Chen-style practice was initially perceived as radically different from other prevalent martial art schools (including established tai chi traditions) of the time. Chen Fake proved the effectiveness of Chen-style tai chi through various private challenges and even a series of lei tai matches.[4] Within a short time, the Beijing martial arts community was convinced of the effectiveness of Chen-style tai chi and a large group of martial enthusiasts started to train and publicly promote it.

The increased interest in Chen-style tai chi led Tang Hao, one of the first modern Chinese martial art historians, to visit and document the martial lineage in Chen Village in 1930 with Chen Ziming.[10] During the course of his research, he consulted with a manuscript written by 16th generation family member Chen Xin (陳鑫; Ch'en Hsin; 1849–1929) detailing Chen Xin's understanding of the Chen Village heritage. Chen Xin's nephew, Chen Chunyuan, together with Chen Panling (president of Henan Province Martial Arts Academy), Han Zibu (president of Henan Archives Bureau), Wang Zemin, Bai Yusheng of Kaiming Publishing House, Guan Baiyi (director of Henan Provincial Museum) and Zhang Jiamou helped publish Chen Xin's work posthumously. The book entitled Chen Style Taijiquan Illustrated and Explained (太極拳圖說 see tai chi classics) was published in 1933 with the first print run of thousand copies.[11]

For nearly thirty years, until his death in 1958, Chen Fake diligently taught the art of Chen-style tai chi to a select group of students. As a result, a strong Beijing Chen-style tradition centered around his "New Frame" variant of Chen Village "Old Frame" survived after his death. His legacy was spread throughout China by the efforts of his senior students.

The Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) resulted in a period of Chen-style tai chi decline. Radical students led a campaign to suppress the "Four Olds", which included the practice of martial arts. Training facilities were closed and practitioners were prosecuted. Many Chen masters were publicly denounced. For example, Chen Zhaopei was pushed to the point of attempting suicide,[12] and Hong Junsheng was left malnourished. Training was continued in secret and at great personal risk ensuring the continuation of the tradition.

During the Era of Reconstruction (1976–1989), the policy of repression of traditional Chinese culture was reversed. Under this new climate, Chen-style tai chi was once again allowed to be practiced openly. Through a series of government-sponsored meetings and various provincial and national tournaments, Chen-style tai chi regained its reputation as an important branch of Chinese martial arts. In addition, those meetings created a new generation of Chen-style teachers.

The start of the internationalisation of Chen-style can be traced to 1981. A tai chi association from Japan went on a promotional tour to the Chen village. The success of this trip created interest in Chen-style tai chi both nationally and internationally. Soon tai chi enthusiasts from other countries started their pilgrimage to Chen village. The increasing interest led all levels of the Chinese governments to improve the infrastructure and support of the village including the establishment of martial art schools, hotels and tourist associations.[13]

In 1983, martial artists from the Chen village received full government support to promote Chen-style tai chi abroad. Some of the best Chen stylists became international "roaming ambassadors" known as the "Four Buddha Warrior Attendants". Those four Chen stylists including Chen Xiaowang,[14] Chen Zhenglei,[15] Wang Xian (王西安)[16] and Zhu Tiancai (朱天才)[17] traveled relentlessly giving global workshops and creating an international group of Chen-style practitioners.

Other well known Chen teachers active in China or overseas include:

- Chen Yu (陳瑜; grandson of Chen Fake)[18]

- Chen Bing (陳炳; Chen Village)[19]

- Chen Boxiang (陈伯祥; Chen Village)[20]

- Chen Xiaoxing (陳小星; Chen Village)[21]

- Chen Peishan (陳沛山) and Chen Peiju (陳沛匊) have been influential in promoting the less-known Chen Village Small Frame tradition[22]

- Tian Jianhua (田剑华; the last living student of Chen Fake, younger brother of Tian Xiuchen, teaching in Beijing)[23]

- Zhang Xuexin (張學信; 1928-2023 disciple of Feng Zhiqiang; teaching in the US),[24]

- Han Kuiyuan (韩奎元; 1948-), disciple of both Tian Xiuchen and Feng Zhiqiang. He is teaching in Hungary.[25]

- Cheng Jincai (程進才; disciple of Chen Zhaokui; The founder of International Chen Style Tai Chi Development Center, Houston, TX),[26]

- Li Enjiu (李恩久; disciple of Hong Junsheng)[27]

- Joseph Chen Zhonghua (disciple of Hong Junsheng and Feng Zhiqiang; teaching throughout North America),[28]

- Wu (Peter) Shi-zeng (吴仕增; a student of Hong Junsheng in Australia)[29]

- Chen Huixian (陈会贤; Disciple of Chen Zhenglei teaching in the US)[30]

- Chou Wenpei (周文沛; Berkeley, California): Student of Pan Yongzhou, has promoted and documented Chen-style tai chi since 1996.[31]

- Gil Rodrigues, Disciple of Master Chen Ziqiang. He is teaching in Brazil.

In recent decades Chen-style tai chi has come to be recognized as a major style of martial art within China and around the world. A strong Chen tradition have developed in countries such as the US, Canada, Britain, Austria, New Zealand, Germany, Italy, Czech Republic, Japan, Singapore and Malaysia.

Tai chi lineage tree with Chen-style focus

The story of Chen-style tai chi is rich and complex. The lineage tree is a concise summary and highlights some of the important personalities that contributed to its history. However, there are some missing details that can provide insight to the current understanding of this art.

Chen Xin (1849-1929), 8th generation Chen family member, provided one of the most important written description of the Chen style.[11] He was the grandson of Chen Youshen (陈有恒), 6th generation Chen family member. Chen Youshen was the brother of Chen Youben (陈有本), the creator of Small Frame. Chen Xin's father was Chen Zhongshen and Chen Xin's uncle, Chen Jishen were twins. In that 7th generation Chen family, Chen Zhongshen, Chen Jishen, Chen Gengyun (陈耕耘, the son of Chen Chanxing), Yang Luchan (杨露禅, founder of Yang Style) and Chen Qingping (陈清萍, promoter of Zhaobao style tai chi) were all martial artists with exceptional abilities.

Chen Xin initially trained with his father but his father ordered him to study literature rather than the martial arts. It was only later that he decided to use his literature skills to describe his understanding of the secrets of Chen style. In Chen Xin's generation, his older brother, Chen Yao and his cousin, Chen Yanxi (陈延熙, father of Chen Fake) were considered masters of the Chen style. Chen Xin's legacy is his book and his student, Chen Ziming (陈子明). Chen Ziming, went on to promote Chen style small frame throughout China and wrote books[32] promoting the art. Chen Ziming was in the same generation as Chen Fake.

Forms

Forms, also called Taolu (Chinese: 套路, tàolù: routine, pattern, standard method), play a fundamental role in Chen-style tai chi as choreographed sequences of movements that serve as repositories for various methods, techniques, stances, and types of energy and force production. Within the Chen-style tai chi tradition, there are at least two forms: Yi Lu (First Form) and Er Lu (Second Form). These forms represent the embodiment of the intricate theories unique to the Chen style. In the words of Chen Fake, the last great proponent of the Chen style in the modern era, 'This set of Taijiquan does not have one technique which is useless. Everything was carefully designed for a purpose' ('这套拳没有一个动作是空的, 都是有用的').[8][9] A correct Chen-style tai chi form is grounded in the same fundamental principles, transcending mere external appearances.

Within the Chen-style tai chi umbrella, there are various teaching traditions, and their practices may often vary somewhat from one another - often due to differences in how they cultivated their skill throughout their decades of practice. Chen Ziming wrote, "In the beginning of the training, conform to patterns. At an intermediate level, you may change patterns. Then finally, patterns are driven by spirit.”[33] Over time and distance within the Chen style, these interpretations have given rise to subdivisions. Each variation is influenced by its own history and the training insights of master teachers. The current subdivisions include historical training methods from Chen Village, forms derived from the lineage of Chen Fake (commonly known as Big or Large Frame, including Old Frame and New Frame), Chen family Small Frame attributed to teachings within the Chen village, training methods from Chen Fake's students, and closely related traditions like Zhaobao tai chi. In the past, the effectiveness of training methods was determined through actual combat, but such tests of skill are less common in the modern era. With no recognized central authorities for tai chi, authenticity is often determined through anecdotal stories or appeals to historical lineage. However, the Chen style practitioner upholds a more stringent requirement, focusing on the underlying principles rather than external appearances.[34]

As practitioners delve into the different frames and forms within Chen-style tai chi, they strive to honor and embody the profound principles handed down through the Chen Family's tai chi legacy. While uncertainties may exist due to the lack of written sources and the reliance on oral traditions, practitioners endeavor to interpret each subdivision. The Chen Family's tai chi legacy continues to captivate practitioners, as they aspire to unlock the essence of Chen-style tai chi and integrate its profound principles into their dedicated practice.

Fundamental principles

The fundamental principles of Chen-style tai chi find their roots in various poems, stories from Chen Village, and the teachings of Chen Fake. These principles, which encapsulate the essence of the art, can be summarized as follows:[6][35]

- Keep the head suspended from above (虚领顶劲, xū lǐng dǐng jìn)

- Keep the body centered and upright (立身中正, lìshēn zhōngzhèng)

- Loosen the shoulders and sink the elbows (松肩沉肘, sōng jiān chén zhǒu)

- Hollow the chest and settle the waist (含胸塌腰, hán xiōng tā yāo)

- Drop the heart/mind energy [to the dantian] (心气下降, xīn qì xià jiàng)

- Breathe naturally (呼吸自然, hū xī zì rán)

- Loosen the hips and keep the knees bent (松胯屈膝, sōng kuà qū xī)

- The crotch is arch shaped (裆劲开圆, dāng jìn kāi yuán)

- Empty and solid separate clearly (虚实分明, xū shí fēn míng)

- The top and bottom coordinate (上下相随. shàng xià xiāng suí)

- Hardness and softness facilitate each other (刚柔相济, gāng róu xiāng jì)

- Fast and slow alternate (快慢相间, (kuài màn xiāng jiàn)

- The external shape travels a curve; (外形走弧线, wài xíng zǒu hú xiàn)

- The internal energy travels a spiral path (内劲走螺旋, nèi jìn zǒu luó xuán)

- The body leads the hand (以身领手, yǐ shēn lǐng shǒu)

- The back waist is an axis (以腰为轴, yǐ yāo wèi zhóu)

Historical forms from Chen Village

The term 'historical forms' refers to training methods described in traditional boxing manuals from Chen Village, as well as through oral recollections and verbal histories.[36][8][9] Unfortunately, these forms are considered lost and are no longer practiced.

Chen Wangting, a ninth generation Chen Village leader, was credited with the creation of seven routines:[6]

- The First Set of Thirteen Movements with 66 Forms (头套十三式 66式)

- The Second Set with 27 forms (二套 27式)

- The Third Set with 24 forms also known as the Four Big Hammer Set (三套24式 又称大四套捶)

- Red Fist with 23 forms (红拳 23式)

- The Fifth Set with 29 forms (五套29式)

- The Long Fist with 108 forms (长拳 108式)

- The Cannon Fist with 71 forms now commonly known as the Second Form, Erlu (炮捶 俗称二路71式)

- Weapon forms including the broadsword, the sword, the staff and the hook (器械 刀, 枪, 棍, 钩等多种)

- Two man training routines (对练套路)

The first five sets were a curriculum known as the five routines of tai chi (太極拳五路). The 108-form Long Fist (Boxing) (一百零八勢長拳, Yībǎi líng bā shì zhǎngquán) and a form known as Cannon Fist (Pounding) (炮捶, Pào chuí) were considered to be a separate curriculum.

Most of these forms were not commonly practiced after the time of Chen Changxing (陳長興, 1771–1853) and Chen Youben (陳有本, 1780–1858) of the 14th generation. Around that time, the curriculum was streamlined into two forms representing the two paths of curricula, the Yilu, the First Path, or Road, trained by the Thirteen Movements (十三势, Shísān shì) form, and the Erlu, the Second Path, trained by the Cannon Fist (炮捶, Pào chuí) form.

In order to preserve it, Chen Xin (1849-1929) recorded the 66-movement Thirteen Postures (十三势) form as it was passed to him in his book, Chen Family Taijiquan Illustrated and Explained (陳氏太極拳圖說, Chén shì tàijí quán túshuō).

Push hands as a means of training was not mentioned in the Chen historical manuals, rather it was described as a form of pair training. From a military perspective, empty-hand training was a foundation for weapons training and push hands training was a method to prevail in the bind (two weapons locked or pressed against each other). In terms of weapons, the Chen clan writings described a variety of weapons training including: spear, staff, swords, halberd, mace, and sickles, but the manuals specifically described training for spear (枪, qiāng), staff (棍, gùn), broadsword (saber)(刀, dāo), and straight sword (剑, jiàn).

Existing Chen Village forms

The two path represents the two main forms used in any Chen-style tai chi training. The main variants in training with direct connection to Chen Village are: Large Frame, Small Frame, New Frame and Old Frame. These frames developed and passed down by key figures such as Chen Zhaopei and Chen Zhaokui, embody distinct lineages and training approaches. From the dedication of Chen Zhaopei in preserving the art to Chen Zhaokui's introduction of innovative practices in New Frame, the evolution of Chen-style tai chi continues. The Small Frame gaining international recognition, shares similarities with teachings by Chen Xin and Chen Ziming. Despite their differences, these frames share common origins and principles, making them integral to the Chen-style tai chi system.

Two-path curriculum

Today, the two-path curriculum, originally developed by Chen Changxing, a master of the 14th generation, serves as the foundation for training in all branches of Chen-style tai chi. Each path is typically associated with a specific form: the First Form (Yi Lu), also known as the Thirteen Movements (十三势, Shísān shì), and the Second Form (Er Lu), sometimes referred to as Cannon Fist (炮捶, Pào Chuí). These paths follow distinct approaches to training.

The Yilu form initiates students into the fundamental principles of tai chi. It emphasizes essential aspects such as footwork, stances, and overall movement. Internal development, including silk reeling training, is also a key focus. The Yilu form aims to teach practitioners how to synchronize their minds, bodies, and internal energy in accordance with tai chi principles. Chen-style practitioners describe the Yilu form as having large and stretching movements, brisk and steady footwork, a naturally straight body, and the integration of internal energy throughout the entire body. (拳架舒展大方,步法轻灵稳健,身法中正自然,内劲统领全身。)[37]

The Yilu form requires the practitioner to closely coordinate their mind, intent, internal energy, and body. Externally, the form's movements follow an arc, while internally, the energy flows in a spiral pattern. This interplay between soft external actions and corresponding hard internal actions is a hallmark of the Yilu form. (练习时,要求意、气、身密切配合,外形走弧线,内劲走螺旋,缠绕圆转,外柔内刚。)[38] Training application on this path is through the method of push hands. Push hands, a partner exercise, is commonly used to apply the principles learned in Yilu training. Push hands involves controlling an opponent through yielding, attaching, redirecting, manipulating, grappling, breaking structure, and other skills. Originally focused on refining the usage of tai chi, push hands has evolved over time into a competitive sport that is somewhat disconnected from its martial roots.

Erlu, the Second Path, typically comes after a student has achieved proficiency in Yilu. Erlu training concentrates on expressing the internal skills cultivated during Yilu practice. The applications in Erlu incorporate more striking, jumping, lunging, and athletically demanding movements. While Yilu emphasized using the body to guide the hands (以身领手, yǐ shēn lǐng shǒu), Erlu shifts the emphasis to using the hands to lead the body (以手领身, yǐ shǒu lǐng shēn). In terms of appearance, the Erlu form is often executed at a faster pace and is characterized by more explosive movements compared to Yilu. The intent of Erlu is focused on self-defense, with each posture training the practitioner for strikes or breaks rather than grappling. The techniques in Erlu employ smaller and tighter circles to generate power.[39]

It is worth noting that while the Cannon Fist form is widely taught in various traditions, very few teach the self-defense skills associated with Erlu due to their inherent dangers. Even when taught, Erlu self-defense techniques are typically reserved for a select few trusted students. In some training traditions today, both forms may be employed to train practitioners in each path of the curriculum.

Frames - Large and Small, Old and New

Within the Chen Family, there are currently three main variants, or frames, of Chen-style forms that are practiced today. Each frame represents a distinct perspective within the Chen-style tai chi tradition. The concept of frames (架, jià, frame, rack, framework) rrefers to the general width of stances and range of motion employed in the forms. For example, in the Large Frame (大架, Dà jià ), the standard horse stance is at least two and a half shoulder widths wide, and the hand techniques appear large and expansive. On the other hand, the Small Frame (小架, Xiǎo jià), the standard horse stance is two shoulders width wide and the hand techniques are perceived as generally shorter and more compact.

The classification of all tai chi styles into "frames" based on the size of stance and other criteria was introduced by Tang Hao in the late 1930s and became common practice by the 1950s.[40] Chen Fake's Chen-style tai chi was classified as Large Frame, while Wu Yuxiang's Wu (Hao)-style tai chi was classified as Small Frame at the time, based on research into the Hao family branch. Chen Qingping, Wu Yuxiang's Chen-style teacher, is associated with the Zhaobao style which includes large and small frame training, and this also suggested a small frame lineage. To simplify matters for new students, the Chen Family divided their tai chi into Large Frame, originating from Chen Fake, and Small Frame, associated with Chen Ziming. Large Frame may be further divided: Old Frame (老架, Lǎo jia) taught in the Chen Village by Chen Zhaopei and New Frame (新架, Xīn jià) taught in the Chen Village by Chen Zhaokui. Both teachers of Large Frame were students of Chen Fake.

Although the frames share more similarities than differences, the variations provide valuable insights. Despite the existence of clear lineage charts, many students are known to have trained with multiple teachers, often without strict adherence to a single lineage. For instance, Chen Zhaopei studied with his father Chen Dengke, his father's uncle Chen Yanxi, and Yanxi's son Chen Fake, all of whom are now considered practitioners of the Large Frame. However, Chen Zhaopei also studied theory with Chen Xin, who is now recognized as a Small Frame practitioner.[41]

Large Frame: Old Frame (Laojia) tradition

In 1958, Chen Zhaopei (陈照丕, 1893-1972), nephew of Chen Fake, returned to visit Chen Village. There, he found that war, hardship, and migration had reduced Chen Style practitioners still teaching in the Village to a couple of aging teachers with a handful of students. He immediately took early retirement and returned to the hardships of village life in order to ensure the survival of his family martial art.[41][42] His teachings are known today as Laojia (Old Frame).

In Laojia, there are 72 moves in the First Form and 42 moves in the Second Form. Chen Zhaopei recorded photographs of his First Form with instructions in a book, General Explanations of Taiji Boxing Fundamentals (太極拳學入門總解, Tàijí quán xué rùmén zǒng jiě) published in 1930.[43] In Chen Village, Laojia is considered the foundation form. Because it is steady, fluid, and readily comprehended, it is always taught first.[44]

Large Frame: New Frame (Xinjia) tradition

Near the end of the Cultural Revolution and later after Chen Zhaopei's death in 1972, tai chi practitioners in Chen Village petitioned Chen Zhaokui (陈照奎, 1928 – 1981), Chen Fake's only living son, to come and continue their education in the art. When Chen Zhaokui visited Chen Village to assist and later succeed Chen Zhaopei in training a new generation of practitioners, (e.g. the "Four Jingang," aka the "Four Tigers": Chen Xiaowang (陈小旺), Chen Zhenglei, Wang Xi'an (王西安), and Zhu Tiancai (朱天才)), he taught Chen Fake's practice methods that were unfamiliar to them. He made three separate visits, totaling under two years. Zhu Tian Cai, who was a young man at the time, claimed that they all started calling it "Xinjia" (New Frame) because it seemed adapted from the teachings they had previously learned from Chen Zhaopei, which they called “Laojia” (Old Frame).

In Xinjia, there are 83 moves in the First Form and 71 moves in Second Form. Chen Xiaoxing, Chen Xiaowang’s brother and a student of Chen Zhaokui, said the primary differences between the Xinjia and Laojia are the small circles, which highlight the turning of the wrists and make visible the folding of the chest and waist.[44] Xiongyao zhedie (chest and waist layered folding) is the coordinated opening and closing of back and chest along with a type of rippling wave (folding) running vertically up and down the dantian/waist area, connected to twisting of the waist/torso. Rotations of the waist and dantian become more apparent in Xinjia.[44]

Chen Zhaopei also added tuishou (push hands) and martial application methods over a series of visits. Chen Zhaokui's teaching of the Xinjia was explicitly practiced with the purpose of developing tangible and effective martial arts methods based on spiral energy usage, fajin (energy release) and qinna (joint locking) movements.[44] The stances in Xinjia tend to be more compact with the goal of training for better mobility in fighting applications, while they still remain quite low. This includes more dynamic, springing and jumping movements.[44] This form tends to emphasize manipulation, seizing and grappling (qin na) and a tight method of spiral winding for both long and shorter range striking. Zhu Tian Cai has commented that the Xinjia emphasizes the silk reeling movements to help beginners more easily learn the internal principles in form and to make application more obvious in relation to the Old Frame forms. The New Frame Cannon Fist is generally performed faster than other empty hand forms.

Chen Xiaoxing also emphasized that "the fundamental principles of the two frames, (Laojia and Xinjia), are the same with regards to postural requirements and movement principles. Both require the practitioner to exhibit movements that are continuous, round and pliant, connecting all movements section by section and closely synchronising the actions of the upper and lower body....The Old and New Frames should not be viewed as different entities because both are foundation forms. If you look beyond the superficial differences, the Old Frame and New Frame are the same style, sharing the same origin and guiding principles. In Chen Village, people have the advantage of knowing both the first routines."[44] However, because of common fundamentals and training methods, either frame, Laojia or Xinjia, can each be trained as a complete curriculum.

Small Frame tradition

The Small Frame (小架, Xiǎo jià) is the most recent subdivision of the Chen Family martial art to gain international recognition. It closely resembles both the 66-movement form described in Chen Xin's (陈鑫, 1849-1929)[45] book Chen Family Taijiquan Illustrated and Explained (陳氏太極拳圖說, Chén shì tàijí quán túshuō)[46] published posthumously in 1933 and the photographed form of his student, Chen Ziming (陳子明, d.:1951), in his book Inherited Chen Family Taiji Boxing Art’’ (1932).[33]

The name, nature, and teachings of this Chen subdivision have been a source of confusion for nearly a century. Chen Ziming, in describing the lineage of his art from Chen Wangting to himself, mentioned changes in the Chen Village that led to the division of the art into "old frame" (laojia) of Chen Wangting and "new frame" (xinjia) that he learned. This was the first published reference dividing Chen-style tai chi into frames.[33] Chen Xin's book did not mention frames[43][46] since there was little or no formal distinction between lineages or branches of teaching methods within the Chen Village.[33][41][47][48][49]

In Xiaojia, there are 78 moves in the First Form and 50 moves in the Second Form. And, some lineages teach additional forms that may date back to Chen Wangting's original system. Xiaojia is known mainly for encouraging students to seek to internalize spiral movements while practicing the form. Most spiral silk reeling action is within the body. The limbs are the last place the motion occurs. Stances seem smaller because the feet do not turn outward in order to maintain a rounded crotch, the front hip is allowed to fold, and the pelvis is not forced forward. The palms must stay below the eyebrows and may not cross the center line of the torso. The body is constrained from shifting left and right horizontally except when stepping. Fajin may be expressed, but it is more calm.[49]

Despite its growing international recognition, authentic Xiaojia instructors are still rare, especially internationally. However, this is beginning to change, and there is a growing body of online and video material available.

Closely related Chen traditions

Since the popularization of Chen-style tai chi by Chen Fake and the discovery of the rich martial heritage of Chen Village, there have been numerous training methods claiming to be part of Chen-style tai chi. According to Hong, a close student of Chen Fake, only direct descendants of the Chen family can truly consider themselves practitioners of Chen Family tai chi.[9] All other practitioners of Chen-style tai chi are regarded as Chen stylists (陈式) as long as they adhere to the unique principles of Chen style. There are several closely related Chen traditions that are recognized, including the Chen tai chi Beijing Branch, which continues the training of Chen Fake, Xinyi Hunyuan tai chi by Feng Zhiqiang, the Practical Method of Hong Junshen, Zhaobao tai chi, and modern synthetic forms.

Beijing Branch

After Chen Fake’s death, his students began passing on what they had learned to their own students. These teachers and their students collectively are referred to as the Beijing Branch. The Beijing forms are similar to those called Xinjia (New Frame, 新架) by Chen Zhaokui's students in Chen Village. They are attributed to Chen Fake, and some regard him as the originator of the branch.

When Chen Zhaokui (Chen Fake' son) returned to Chen Village, he taught Chen Fake's form. The unfamiliar teachings became coined as "Xinjia" (New Frame), because they seemed adapted from the earlier frame they had learned, which they then called Old Frame (Laojia). Because of this distinction, Chen Fake's disciples in Beijing decided to name their master's style "Beijing Chen Style" to differentiate it from Chen Village Xinjia, and they considered the 1st generation as Chen Fake (17th generation member of Chen clan and 9th generation Grandmaster of Chen-style tai chi).[50] This means that the Beijing disciples of Chen Fake continued the Chen-style tai chi master-lineage (10th, 11th, 12th, 13th generation, etc...), but they usually start counting from Chen Fake.

Important for the diffusion of this style was Tian Xiuchen (田秀臣; 1917–1984; 10th generation master of Chen-style tai chi and 2nd generation master of Beijing Chen-style tai chi),[51] the disciple that learned Chen style with Chen Fake for the longest continuous time. He introduced tai chi teaching in Chinese universities. The lineage of this branch continued with masters Tian Qiutian, Tian Qiumao and Tian Qiuxin (11th generation Chen style and 3rd generation Beijing Chen Style).

Another notable Beijing master is Chen Yu (19th generation member of Chen clan and 11th generation master of Chen-style tai chi and 3rd generation master of Beijing Chen-style tai chi), Chen Zhaokui's son (Chen Fake's grandson), who studied under his father's supervision starting at seven years old.[52] Oftentimes, his style is called "Chen Taijiquan Gongfu" or "Gongfujia", since Chen Yu rebuts the idea that either his father or grandfather (i.e. Chen Fake) ever called their style "Xinjia" or believed that what they practiced was newer than other branches of Chen-style tai chi.

Xinyi Hunyuan tai chi

Chen-style Xinyi Hunyuan tai chi (陈式心意混元太极拳), called Hunyuan tai chi for short, was created by Feng Zhiqiang (冯志强; 1928-2012; 10th generation master of Chen-style tai chi and 2nd generation master of Beijing Chen-style tai chi),[53] one of Chen Fake's senior students and a student of Hu Yaozhen (胡耀貞; 1897-1993). It is much like the traditional forms of the Beijing branches of Chen-style tai chi with an influence from Xing Yi Quan and Qigong, learned from Hu Yaozhen and Tongbeiquan, learned in his youth. Feng, who died on 5 May 2012, was widely considered the foremost living martial artist of the Chen tradition.

"Hun Yuan" refers to the strong emphasis on circular, "orbital" or spiraling internal principles at the heart of this evolved Chen tradition. While such principles already exist in mainstream Chen-style, the Hun Yuan tradition develops the theme further. Its teaching system pays attention to spiraling techniques in both body and limbs, and how they may be harmoniously coordinated together.

Specifically, the style synthesizes Chen-style tai chi, Xinyi, and Tongbeiquan (both Qigong and, to a lesser degree, martial movements), the styles studied by Feng Zhiqiang at different times. Outwardly, it appears similar to the New Frame Chen forms and teaches beginners/seniors a 24 open-fist form as well as a 24 Qigong system.

The training syllabus also includes 35 Chen Silk-Reeling and condensed 38 and 48 open-fist forms in addition to Chen Fake's (modified) Big Frame forms (83 and 71).

The Hunyuan tradition is internationally well organized and managed by Feng's daughters and his long-time disciples. Systematic and comprehensive theory/practice international teaching conventions are held yearly. Internally trained instructors teach tai chi for health benefits with many also teaching Chen martial-art applications. Feng's specially trained "disciple instructors" teach Chen internal martial art skills of the highest level.

Grandmaster Feng in his late years rarely taught publicly but devoted his energies to training Hun Yuan instructors and an inner core of nine "disciples" that included Cao Zhilin, Chen Xiang, Pan Houcheng, Wang Fengming and Zhang Xuexin.

Han Kuiyuan (韩奎元; 1948-), who is another recognized disciple of Feng Zhiqiang (and formerly Tian Xiuchen), has been teaching Chen style Xinyi Hunyuan tai chi in Hungary since 1997.

The Practical Method

This branch of Chen-style tai chi descends through the students of Hong Junsheng, a senior student of Chen Fake, who became a disciple in 1930 and studied daily through 1944 when Hong moved to his ancestral home in Jinan, Shandong. Hong continued to practice and returned to study with Chen Fake in 1956. Modifications to the original forms taught by Chen Fake to Hong and later used in the Practical Method were made during this visit.

Hong appended the term, "Practical Method" (实用拳法, shí yòng quán fǎ), to his teaching method to emphasize the martial aspects of his study and training, as well as the harmonized training syllabus joining gōng (功) and fǎ (法) aspects of training within the Yilu (first road).[54] Some started calling the system Hong-style tai chi, but Hong Junsheng objected to this designation. He claimed he was not the creator of anything. Everything he taught was Chen-style tai chi as taught to him by his teacher, Chen Fake.

Hong taught, in traditional Chen-style tai chi, the First Path (Yilu) used the First Form, without explosive fajin (发劲, Send out Strength), and related foundation exercises as a curriculum focused on learning to control one's self and move in a tai chi manner. Push hands was the method to learn how to use the First Form’s movements to control opponents. With these situational control skills, the Second Path (Erlu), could be learned as self-defense with the objective of injuring and disabling an attacker as quickly as possible. For this curriculum, the First Form was repurposed to include fajin and the Second Form added. Training methods also included sparring (散手, sǎn shǒu), fighting technique (拳法, quán fǎ: ) and weapons training. Today, however, Yilu and Erlu are used generally to refer to the First and Second Forms, respectively, and teachers often use Second Path skills to demonstrate martial efficacy while teaching the First Form.

In the Practical Method, there are 81 moves in the First Form and 64 moves in the Second Form, which may be joined together, not repeating the joining move, for a form of 144 moves. The sequence and names of the movements are similar to Xinjia and Beijing forms. The Second Form was reduced by naming fewer, but not deleting, moves. However, the manifested small circles and turning of the wrists characteristic of Xinjia are reduced to spirals and helices and internalized. This gives the Practical Method forms more of the look of Laojia.

Hong said Chen Fake taught, "Taijiquan is learned according to the rules (规矩, gui ju)." In this regard, theoretically, the Practical Method aligns closely with the writings of Chen Xin[46] and, hence, Xiaojia,[49] except that one foot is allowed to turn outward 45° so that both hips (kua, 胯) may stay open to round the crotch. Pragmatic oral instructions were passed from Chen Fake to illuminate theoretical principles,[55] such as: Lead inward with the elbow do not lead inward with the hand; Go out with the hand do not go out with the elbow. (收肘不收手,出手不出, Shōu zhǒu bù shōu shǒu, chū shǒu bù chū zhǒu.); Only rotate don't move. (只转不动, Zhǐ zhuǎn bù dòng); Better to advance one hair than to retreat one foot. (宁进一毫,不退一尺, Níng jìn yī háo, bù tuì yī chǐ); and many others.

One innovation by Hong Junsheng for teaching movement in the form was the nomenclature, "positive" and "negative" circles. Previously, shùn chán (顺缠, following coiling) and nì chán (逆缠, opposing coiling) were used to describe silk-reeling rotations and inward and outward arcs and circles of the extremities. This worked well for describing the longitudinal rotations of the arms and legs, but arcs and circles would often have both shun and ni rotations within them. Hong found it confusing to students to describe complete revolutions. A Positive (formerly shùn) Circle rotates inward (shùn chán) at the bottom and outward (nì chán) at the top, and a Negative (formerly nì) Circle rotates inward (shùn chán) at the top and outward (nì chán) at the bottom. This terminology has been adopted by teachers of many styles of martial arts.

Currently, Li Enjiu is the Standard Bearer and Chen Zhonghua is International Standard bearer of Chen-style tai chi Practical Method. The Chen Style tai chi Practical Method is taught by teachers around the world.

Zhaobao tai chi and Chen-style tai chi forms

Zhaobao Village (Zhaopucun 赵堡村) lies about 2 miles (3 km) to the northeast of Chen Village. Since the village was a local trade center and not settled by a single family, Zhaobao tai chi is a true village martial art, and the style was passed master to disciples among the villagers. Village martial arts developed as skills could be brought to a village. There they were merged with prior knowledge and evolved and were taught primarily for common defense. Zhaobao tai chi designates several lineages and traditions rather than a single one. Also, tai chi forms from other nearby villages get grouped with Zhaobao, such as Huleijia (Sudden thunder frame), even though they are not directly related.

The villages proximity allowed residents of the Chen Village to intermarry or move to Zhaobao, so there has been an influence from Chen tai chi for centuries. Several Zhaobao lineages trace their roots to Jiang Fa (1574-1655), a servant to Chen Wangting. They claim that Jiang Fa moved to Zhaobao Village and taught tai chi there for a number of years.

Several other notable Chen Family members also lived in Zhaobao. The best documented was Chen Qingping, who moved and taught there. Some Zhaobao lineages include Chen Qingping. So, Zhaobao tai chi shares many stylistic similarities with Chen-style tai chi, particularly Xiaojia, because it was influenced by Chen Family stylists. His disciples, such as He Zhaoyuan and Wu Yuxiang, promoted this unique style.

Zhaobao tai chi is village style rather than one of the tai chi "family" styles, and it does not originate through the teaching interaction of Chen Changxing with Yang Luchan as do other styles of tai chi. Despite the similarities in appearance to Chen tai chi, this style has its own theory, philosophy, and long history. It is truly a different "style" of tai chi. Some consider it to be a distinct and separate traditional Chinese martial art altogether.

Modern Chen forms

Similar to other family styles of tai chi, Chen-style has had its frame adapted by competitors to fit within the framework of wushu competition. A prominent example is the 56 Chen Competition form (Developed by professor Kan Gui Xiang of the Beijing Institute of Sport under the auspice of the Chinese National Wushu Association. It is composed based on the lao jia routines (classical sets), and to a much lesser extent the 48/42 Combined Competition form (1976/1989 by the Chinese Sports Committee developed from Chen and three other traditional styles).

In the last ten years or so even respected grandmasters of traditional styles have begun to accommodate this contemporary trend towards shortened forms that take less time to learn and perform. Beginners in large cities don't always have the time, space or the concentration needed to immediately start learning old frame (75 movements). This proves all the more true at workshops given by visiting grandmasters. Consequently, shortened versions of the traditional forms have been developed even by the "Four Buddha’s warriors." Beginners can choose from postures of 38 (synthesized from both lao and xin jia by Chen Xiaowang), 19 (1995 Chen Xiaowang), 18 (Chen Zhenglei) and 13 (1997 Zhu Tiancai). There is even a 4-step routine (repeated 4 times in a circular progression, returning to start) useful for confined spaces (Zhu Tiancai).

In a sense, shorter and well composed sets of forms are modernizing tai chi to suit modern needs and lifestyle. As well as that some composers incorporated up to day medical knowledge to improve tai chi's efficacy for health and wellness.

Weapon forms

Chen Tai Chi has several unique weapon forms.

Additional training

Before teaching the forms, the instructor may have the students do stance training such as zhan zhuang and various qigong routines such as silk reeling exercises.[56]

Other methods of training for Chen-style using training aids including pole/spear shaking exercises, which teach a practitioner how to extend their silk reeling and fa jing skill into a weapon.[5]

In addition to the solo exercises listed above, there are partner exercises known as pushing hands, designed to help students maintain the correct body structure when faced with resistance. There are five methods of push hands[56] that students learn before they can move on to a more free-style push hands structure, which begins to resemble sparring.

Martial application

The vast majority of Chen stylists believe that tai chi is first and foremost a martial art; that a study of the self-defense aspect of tai chi is the best test of a student's skill and knowledge of the tai chi principles that provide health benefit. In compliance with this principle, all Chen forms retain some degree of overt fa jing expression.

In martial application, Chen-style tai chi uses a wide variety of techniques applied with all the extremities that revolve around the use of the eight gates of tai chi to manifest either kai (expansive power) or he (contracting power) through the physical postures of Chen forms.[1] The particulars of exterior technique may vary between teachers and forms. In common with all neijia, Chen-style aims to develop internal power for the execution of martial techniques, but in contrast to some tai chi styles and teachers includes the cultivation of fa jing skill.[5] Chen family member Chen Zhenglei has commented that between the new and old frame traditions there are 105 basic fajin methods and 72 basic Qinna methods present in the forms.

References

- Guang Yi, Ren (2003). Taijiquan: Chen 38 form and applications. 364 Innovation Drive, North Clarendon VT: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 0-8048-3526-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - Wile, Douglas (1995). Lost T'ai-chi Classics from the Late Ch'ing Dynasty (Chinese Philosophy and Culture). State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2654-8.

- Wile, Douglas (1983). Tai Chi Touchstones: Yang Family Secret Transmissions. Sweet Ch'i Press. ISBN 978-0-912059-01-3.

- Chen, Mark (2004). Old frame Chen family Taijiquan. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books : Distributed to the book trade by Publishers Group West. ISBN 978-1-55643-488-4.

- Gaffney, David; Sim, Davidine Siaw-Voon (2002). Chen Style Taijiquan : the source of Taiji Boxing. Berkeley, Calif.: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-55643-377-1.

- 余功保 (2006). Chinese Taijiquan dictionary(中国太极拳辞典). 人民体育出版社. ISBN 978-7-5009-2879-9.

- Szymanski, Jarek. "The Origins and Development of Taijiquan (tr. from "Chen Family Taijiquan - Ancient and Present" published by CPPCC (the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference) Culture and History Committee of Wen County, 1992)". Retrieved 16 June 2011.

- 洪均生 (1989). 陈式太极拳实用拳法/: 十七代宗师陈发科晚年传授技击精萃. 山东科学技术出版社. ISBN 978-7-5331-0640-9.

- Junsheng Hong (2006). Chen style taijiquan practical method: theory. Zhonghua Chen (trans.). Hunyuantaiji Press. ISBN 978-0-9730045-5-7. Retrieved 18 January 2011.

- Brian Kennedy (8 January 2008). Chinese Martial Arts Training Manuals: A Historical Survey. Blue Snake Books. pp. 50–. ISBN 978-1-58394-194-2. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- Chen, Xin (1999). "Illustrated Explanations of Chen Family Taijiquan". ChinaFromInside.com. Jarek Szymanski. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- Cheng, Jin Cai (June 13, 2004). "Remembering Grandmaster Chen Zhaokui". International Chen Style Tai Chi Development Center. Retrieved 2011-01-22.

- Burr, Martha (1999). "Chen Zhen Lei : Handing Down the Family Treasure of Chen Taijiquan". Kung Fu Magazine. Retrieved 2011-01-24.

- Chen (陳 ), Xiaowang (小旺). "Chen Xiaowang World Taijiquan Association". Chen Xiaowang World Taijiquan Association. Retrieved 2023-06-07.

- "Chen Zhenglei Website (陈正雷网站)". Chen Zhenglei Taijiquan Federation 陈正雷太极拳联盟. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- "王西安". zh.wikipedia.org. Wikipedia.

- "Zhu Tiancai [National Senior Martial Arts Coach (朱天才[国家高级武术教练)]". Douyin Encyclopedia (抖音百科). Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- Spivack, Marin. "Chenyu 陈瑜". Beijing Chen Zhaokui Taijiquan Association. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- "Chen Bing Taiji Academy (陳炳太極院)". Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- "陈伯祥 (Chen Boxiang)". Tai Chi Inheritance Network (太极拳传承网). Wenxian Taiji Xiangyin Information Industry Co (温县太极乡音信息产业有限公司). Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- "陳小星 (Chen Xiaoxing)". Tai Chi Inheritance Network (太极拳传承网). Wenxian Taiji Xiangyin Information Industry Co (温县太极乡音信息产业有限公司). Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- "ISCT - International Society of Chen Taijiquan / 国際陳氏太極拳連盟". Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- "田剑华". YouTube. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- "Zhang Xue Xin (1928–) Chen Style Taiji 19th Generation Master". Feng Zhi-Qiang Chen Style Taijiquan Academy. 2006. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- "Hán Kuíyuán (韩奎元)". Hungarian Chen Style Xin Yi Hun Yuan Tai Ji Quan Association. Magyarországi Chen Stílusú Xin Yi Hun Yuan Tai Ji Quan Egyesület. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- "International Chen Style Tai Chi Development Center". Retrieved 2012-05-15.

- "李恩久 (Li Enjiu)". Tai Chi Inheritance Network (太极拳传承网). Wenxian Taiji Xiangyin Information Industry Co (温县太极乡音信息产业有限公司). Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- Chen, Joseph (2011). "Chen Zhonghua - Chen Style Taijiquan Practical Method and Hunyuan Taiji". Hunyuan Taiji Academy. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- "Peter Wu Shi-zeng". Taiji GongFa. 太极功法. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- "Chen Huixian Taijiquan Academy". Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- "Chen Taichi on-line". Retrieved 2011-08-07.

- 陈子明 (2008). 太极拳精义. 山西科学技术出版社. ISBN 978-7-5377-3011-2.

- Chen (陕), Ziming (子明) (1932). 陳氏世傳太極拳術 THE INHERITED CHEN FAMILY TAIJI BOXING ART. Shanghai, China: 中國武術學會 the Chinese Martial Arts Society [in Shanghai].

- Peter Allan Lorge (2012). Chinese Martial Arts: From Antiquity to the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge University Press. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-521-87881-4.

- 王教练 (6 September 2008). "Chinese Tai Chi Martial Arts in Shanghai (上海太极拳培训学习中心 )". 豆瓣(douban). Retrieved 2015-06-04.

- Szymanski, Jarek (1999). "Brief Analysis of Chen Family Boxing Manuals". ChinaFromInside.com. Jarek Szymanski. Retrieved 15 April 2015.

- Gongbao (功保), Yu (余) (2006). Chinese Taijiquan Dictionary (中国太极拳辞典). People's Sports Publishing House (人民体育出版社). p. 51. ISBN 9787500928799. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- 史, 铁柱 (2011). 陈式太极拳传统一路八十三式-. 中国水利水电出版社发行部. ISBN 978-7-5084-8309-2.

- Santiago, Xavier (2013-02-15). "Yilu & Erlu". PracticalMethod.com. Chen Zhonghua. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Huang, Wenshu [Yuanxiu] (June 15, 1936). "The Skills & Essentials of Yang Style Taiji Boxing and Martial Arts Discussion". Martial Arts United Monthly Magazine Society.

- Chen, Ke San (4 June 2020). "Chen Zhao Pei, My Father". taiji-bg.com. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Gaffney, David (17 March 2016). "Chen Shitong - Chenjiagou's "Taijiquan Hermit"". Talking Chen Taijiquan. Blogger. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- Chen, Zhaopi (1930). General Explanations Of Taiji Boxing Fundamentals.

- Gaffney, David. "Chen Style Old Frame vs. New Frame". Chenjiagou Taijiquan GB. Translation by Davidine Siaw-Voon Sim. Retrieved 23 February 2021.

- "陈氏太极拳家 陈鑫_太极拳家_陈家沟|太极拳|小架|陈式太极拳|陈氏太极拳|陈鑫|陈伯祥|陈伯祥拳术研究会". www.chenboxiang.com. Retrieved 2018-09-16.

- 陈鑫 (July 2006). 陈氏太极拳图说. 山西科技. ISBN 9787537727273.

- Stubenbaum, Dietmar; Pion, Marc (May 2005). "Chen Peishan-Xiaojia, the Small Frame of Chen Family Taijiquan". Cultura martialis - das Journal der Kampfkünste aus aller Welt. Translated by Annemarie Leippert and Neal DeGregorio. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- Szymanski, Jarek. "Brief Analysis of Chen Family Boxing Manuals". www.chinafrominside.com. Jarek Szymanski. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- Jian, Ge (September 2002). "Small Frame of Chen Style Taijiquan". Shaolin Yu Taiji. Translated by Jarek Szymanski (2002–2004).

- "陈发科的纪念馆 - 第9代 - 陈式 - 中华太极拳传承网(TaiJiRen.cn)".

- "田秀臣的纪念馆 - 第10代 - 陈式 - 中华太极拳传承网(TaiJiRen.cn)".

- "Chenyu (19th generation member of Chen clan and 11th generation master of Chen-style taijiquan) 'Chen Style Tai Chi'".

- "冯志强的纪念馆 - 第10代 - 陈式 - 中华太极拳传承网(TaiJiRen.cn)".

- Nulty, T.J. (2017). "Gong and fa in Chinese martial arts". Martial Arts Studies. 3 (3): 50–63. doi:10.18573/j.2017.10098.

- Chen, Zhonghua (May 2005). Gui Ju: Rules of Play for Chen Style Taijiquan. Edmonton, AB, Canada: Unpubllshed Manuscript.

- Gaffney, David; Sim, Davidine Siaw-Voon (2009). "4". The Essence of Taijiquan. Warrington, UK: Chenjiagou Taijiquan GB.

Further reading

- Chen, Zhenglei (2003). Chen Style Taijiquan, Sword and Broadsword. Zhengzhou, China: Tai Chi Centre. ISBN 7-5348-2321-8.