Chief White Eagle

Chief White Eagle (c. 1825 - February 3, 1914) was a Native American politician and American civil rights leader who served as the hereditary chief of the Ponca from 1870 until 1904. His 34-year tenure as the Ponca head of state spanned the most consequential period of cultural and political change in their history, beginning with the unlawful Ponca Trail of Tears in 1877 and continuing through his successful effort to obtain justice for his people by utilizing the American media to wage a public relations campaign against the United States and President Rutherford B. Hayes. His advocacy against America's Indian removal policy following the Ponca Trail of Tears marked a shift in public opinion against the federal government's Indian policy[2] that ended the policy of removal,[3] placing him at the forefront of the nascent Native American civil rights movement in the second half of the 19th century.

White Eagle | |

|---|---|

| Qithaska | |

.png.webp) Chief White Eagle in 1877 | |

| Hereditary chief sovereign of the Ponca | |

| In office 1870–1904 | |

| Preceded by | Iron Whip (1846-1870) |

| Succeeded by | Horse Chief Eagle (1904-1940) |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1825 Niobrara River valley, Northern Great Plains |

| Died | February 4, 1914 (aged 88–89) White Eagle, Oklahoma |

| Resting place | Monument Hill Marland, Oklahoma 36°34′10″N 97°08′41″W |

| Citizenship | Ponca |

| Nationality | Ponca |

| Relations | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

Family history and early life (1825-1847)

White Eagle was born on the ancestral Ponca homeland somewhere near the confluence of the Niobrara River and Missouri River which forms the contemporary South Dakota-Nebraska state line. At the time of his birth, the Ponca form of government was an oligarchy[4] in which the full sovereign power of the Ponca was vested in a hereditary chief sovereign who was counseled by thirteen chiefs—six senior chiefs and seven junior chiefs—who represented the interests of the Ponca citizenry. The chief sovereign served as the head of state and ranking senior chief and the position was a dynastic succession based on male primogeniture. Dynastic rule was vested in White Eagle's direct male line, a dynasty established by White Eagle's paternal grandfather Chief Little Bear late in the 18th century when he assumed power from the traditional sovereigns by heroic feat. At the turn of the 20th century, White Eagle provided ethnographers at the Smithsonian Institution the oral history of how he became hereditary chief sovereign:

"A chief by the name of Little Chief (Zhingaʼgahige) of the Warrior clan (Washa’be) had a son who went on the warpath. Little Chief sat in his tent weeping because he had heard that his son was killed, for the young man did not return. As he wept he thought of various persons in the tribe whom he might call on to avenge the death of his son. As he cast about, he recalled a young man who belonged to a poor family and had no notable relations. The young man's name was Little Bear (Waça’bezhinga).

Little Chief remembered that this young man dressed and painted himself in a peculiar manner, and thought that he did so that he might act in accordance with a dream, and therefore it was probable that he possessed more than ordinary power and courage. So Little Chief said to himself, “I will call on him and see what he can do.” Then Little Chief called together all the other subchiefs and when they were assembled he sent for Little Bear. On the arrival of the young man Little Chief addressed him, saying, “My son went on the warpath and has never returned. I do not know where his bones lie. I have only heard he has been killed. I wish you to go and find the land where he was killed. If you return successful four times, then I shall resign my place in your favor.” Little Bear accepted the offer. He had a sacred headdress that had on it a ball of human hair; he obtained the hair in this manner: Whenever men and women of his acquaintance combed their hair and any of the hair fell out, Little Bear asked to have the combings given to him. By and by he accumulated enough hair to make his peculiar headdress. This was a close-fitting skull cap of skin; on the front part was fastened the ball of human hair; on the back part were tied a downy eagle feather and one of the sharp-pointed feathers from the wing of that bird. He had another sacred article, a buffalo horn, which he fastened at his belt.

Little Bear called a few warriors together and asked them to go with him, and they consented. Putting on his headdress and buffalo horn, he and his companions started. They met a party of Sioux, hunting. One of the Sioux made a charge at Little Bear, who fell over a bluff. The Sioux stood above him and shot arrows at him; one struck the headdress and the other the buffalo horn. After he had shot these two arrows the Sioux turned and fled. Little Bear, who was uninjured, climbed up the bluff, and, seeing the Sioux, drew his bow and shot the man through the head. Besides this scalp Little Bear and his party captured some ponies. On the return of the party Little Bear gave his share of the booty to the chief who had lost his son. Little Bear went on three other expeditions and always returned successful, and each time he gave his share of the spoils to the chief. When Little Bear came back the fourth time the chief kept his word and resigned his office in favor of the young man. Little Bear was my grandfather. When he died he was succeeded by his eldest son, Two Bulls. At his death his brother, Iron Whip (We'gaçapi) who was my father, became chief, and I succeeded him.”

White Eagle's exact birth year is unknown. Various sources place his birth year as early as 1803 and as late as 1840, though both historical estimates are dubious. When White Eagle died in early 1914, American press reports indicated that he was "the oldest Indian in the United States" at 111 years old,[5] placing his birth in 1803, one year prior to the arrival of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804. This report is dubious as White Eagle's father Iron Whip told British author Charles Mackay in 1858 that he was 56 years old,[6] placing his birth year at 1802. As White Eagle was Iron Whip's first born son, there is an equally low probability that he was born in 1840, a year made all the more unlikely as White Eagle was documented as a junior chief on August 8, 1846, when he accompanied a high ranking Ponca delegation that sought to establish diplomatic relationship with Brigham Young's Mormon Pioneers during their emigration to the Great Basin. The delegation was led by White Eagle's aged paternal grandfather Little Bear whose death was recorded by the Mormons in 1846. The Mormons witnessed the transfer of power to Little Bear's eldest son and White Eagle's uncle, Two Bulls, after Little Bear's death. A month later, Two Bulls died and the Mormons again witnessed the transfer of power to White Eagle's father, Iron Whip, who abdicated the hereditary chief sovereignty to White Eagle in 1870, thereby corroborating White Eagle's oral history.

Chieftaincy (1870-1904)

Ponca removal crisis and Ponca Trail of Tears (1870-1877)

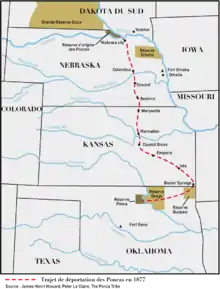

White Eagle's tenure as chief was defined by the unlawful forced removal of the Ponca from their treaty protected territory in the Dakota Territory to the Indian Territory in 1877, in direct violation of the Ponca Treaty of 1865 and American law. Known as the Ponca Trail of Tears, this removal was a six-hundred mile forced march spanning three modern-day states, resulting in numerous deaths en route. The forced march consisted of two parties of Ponca citizens. The first party was composed of approximately 170 Ponca citizens with mixed ancestry and began on April 16, 1877.[7] The second party was to consist of the vast majority of the Ponca citizenry numbering about 500 people, including White Eagle and his vice chief Standing Bear. For nearly a month, White Eagle and Standing Bear resisted the unlawful efforts of Edward Cleveland Kemble, the federal agent sent by President Ulysses S. Grant, to force the Ponca removal by fraud. On April 24, 1877, General William Tecumseh Sherman ordered two companies of American soldiers to Ponca territory to force their compliance.[7] White Eagle said:

Why do I find you here now armed against me? We had always believed that your government had ordered your soldiers to protect those who were peaceful and doing their duty, and to punish and bear arms only against those who had committed crimes. A short time ago I was here at work on my land. I was taken and left in the Indian Territory to find my way back alone. I thought that after being treated in the manner we were by this man [Kemble], that when I came home I would find a protection from my enemy in you. And now, instead, I find you armed against me.” I then turned to Kemble and said, “You profess to be a Christian, and to love God; and yet you would love to see bloodshed. Have you no pity on the tears of these helpless women and children? We would rather die here on our land than be forced to go. Kill us all here on our land now, so that in the future when men will ask, ‘Why have these died?’ it shall be answered, ‘They died rather than be forced to leave their land. They died to maintain their rights. And perhaps there will be found some who will pity us and say, ‘They only did what was right.’

On May 16, 1877, White Eagle again addressed the Ponca people regarding the imminent removal: “My people, we, your chiefs, have worked hard to save you from this. We have resisted until we are worn out, and now we know not what more we can do. We leave the matter into your hands to decide. If you say that we fight and die on our lands, so be it.”[7] White Eagle later recalled what happened afterward, "There was utter silence. Not a word was spoken. We all arose and started for our homes, and there we found that in our absence the soldiers had collected all our women and children together and were standing guard over them. The soldiers got on their horses, went to all the houses, broke open the doors, took our household utensils, put them in their wagons, and pointing their bayonets at our people, ordered them to move. They took all our plows, mowers, hay-forks, grindstones, farming implements of all kind, and everything too heavy to be taken on a journey and locked them up in a large house. We never knew what became of them afterwards. Many of these things of which we were robbed we had bought with money earned by the work of our hands."[8]

The removal lasted 54 miserable days, beginning on May 16, 1877, and ending on July 9, 1877, with many deaths occurring en route.[7] The removal was plagued by torrential rains which flooded the unpaved dirt roads, miring the Ponca in mud for most of the march. A tornado struck the Ponca removal party on June 7, 1877, near Milford, Nebraska, killing one child and injuring many others. The federal agent in charge of the removal described the event as follows:

"The storm, most disastrous of any that occurred during the removal of the Poncas under my charge, came suddenly upon us while in camp on the evening of this day. It was a storm such as I never before experienced, and of which I am unable to give an adequate description. The wind blew a fearful tornado, demolishing every tent in camp, and rending many of them into shreds, overturning wagons, and hurling wagon-boxes, camp equipages, etc., through the air in every direction like straws. Some of the people were taken up by the wind and carried as much as three hundred yards. Several of the Indians were quite seriously hurt, and one child died the next day from injuries received, and was given Christian burial."

The following day, yet another child died.[9] As the Poncas continued their forced march across Kansas, four more people died: a young child named Little Cottonwood died outside Blue Rapids, Kansas, on June 18, two elderly women died south of Manhattan, Kansas, on June 25, and a young child died outside of Emporia, Kansas, on June 30. Two days later, an assassination attempt was made on White Eagle by a disaffected Ponca named Buffalo Chip who held White Eagle responsible for the mounting death toll. The federal removal agent described the chaotic scene of July 2nd his journal as follows: "Broke camp at six o'clock. Made a long march of fifteen miles for Noon Camp, for reason that no water could be got nearer. An Indian became hostile and made a desperate attempt to kill White Eagle, head chief of the tribe. For a time, every male in camp was on the warpath, and for about two hours the most intense excitement prevailed, heightened by continued loud crying by all the women and children."[9] A week after the failed assassination attempt, the Ponca arrived at the Quapaw Agency in the Indian Territory. The federal removal agent wrote:

"July 9th: Broke camp at six o'clock, passing through Baxter Springs at about one o'clock. Just after passing Baxter Springs a terrible thunderstorm struck us. The wind blew a heavy gale and the rain fell in torrents, so that it was impossible to see more than four or five rods distant, thoroughly drenching every person and every article in the [wagon] train, making a fitting end to a journey commenced by wading a river and thereafter encountering innumerable storms. During the last few days of the journey the weather was exceedingly hot, and the teams terribly annoyed and bitten by green-head flies, which attacked them in great numbers. Many of the teams were nearly exhausted, and, had the distance been but little farther, they must have given out. The people were all nearly worn out from the fatigue of the march, and we're heartily glad that the long, tedious journey was at an end, that they might take that rest so much required for the recuperation of their physical natures."

As a result of the unlawful removal, the Ponca suffered severe economic losses, including the loss of their wooden homes, personal property, and agricultural implements. Due to the hasty nature of the unlawful removal perpetuated by Edward Cleveland Kemble and the Hayes administration, the Ponca were removed to a swampy marsh in the Indian Territory and forced to live outside exposed to the elements in a tropical climate. No preparations were made to accommodate the Ponca by the newly inaugurated Hayes administration or Carl Schurz, President Hayes' cabinet secretary responsible for overseeing the removal. Within six months, a further 141 deaths were reported as half of the Ponca population suffered from tropical diseases such as malaria and yellow fever. Among the victims were White Eagle's wife, four of his children, and his father Iron Whip,[10] who preceded him as hereditary chief of the Ponca from 1846 until his abdication in 1870. Iron Whip signed the broken treaty with President Abraham Lincoln in 1865 shortly before Lincoln's assassination. The exact number of deaths is unknown; however, it is known that the death toll exceeded 200 of the 700 Poncas — 30% of the Ponca population — and included the outright extinction of 24 Ponca families.[11]

Advocacy for Native American rights following the Ponca Trail of Tears (1877-1881)

White Eagle led a delegation of Ponca leaders to Washington in the immediate aftermath of the removal in order to confront President Hayes and the American politicians in the Congress regarding the clear illegality of the removal. He and Standing Bear arrived on November 8, 1877.

White Eagle's leadership during the Ponca removal crisis played a central role in the series of events culminating in a landmark civil rights ruling in 1879 recognizing Native Americans as persons due civil rights under the Constitution of the United States for the first time in American history in Standing Bear v. Crook. Immediately following the Ponca removal, White Eagle aggressively sought restoration of the ancestral Ponca homeland from President Hayes and the United States Senate for the American government's violation of the Ponca Treaty of 1865 and its subsequent mismanagement of the Ponca removal. The efforts of both White Eagle and Standing Bear generated significant support from many notable Americans of the time including the poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, former abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and author Helen Hunt Jackson who advocated on behalf of the Ponca by writing the seminal book on Native American civil rights entitled "A Century of Dishonor." Nebraska journalist Thomas Tibbles traveled the country on a speaking tour to raise the money necessary for the Ponca to appeal their removal to the United States Supreme Court. Tibbles “thought that, if the Christian people of this country only knew of these horrors, they would be glad to help White Eagle in getting out of the Indian Territory, and saving from death the little children.”[11] Tibbles appealed to large audiences “not only help White Eagle, but in so doing, burst the infamous Indian Ring,” which was a corrupt segment of political appointees. Tibbles argued that “if they could get standing in the courts for White Eagle and the Ponca, they would put an end to the Indian question and the Indian Wars and at once solve the Indian Question.”[11]

Unlike President Andrew Jackson's forced removals of the Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek, and Seminoles which the American government regarded as legal under the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Ponca removal was widely acknowledged by contemporary Americans to be unlawful from its inception as it was in clear violation of the Ponca Treaty of 1865 and a 1876 Act of Congress which required the federal removal agent, Edward Cleveland Kemble, to obtain White Eagle's consent before removing the Ponca to Indian Territory, which White Eagle refused. As public outrage grew, the Senate created a select committee to investigate the Ponca removal which found that the United States had forced a great injustice upon the Ponca through the misdeeds of Edward Cleveland Kemble, concluding: "If the government expects to exterminate this tribe, it has but to continue the policy of the past few years. The committee can see no valid objection, therefore, to that means of redress which comes nearest to putting these Indians in precisely the condition they were in when E.C. Kemble undertook, without authority of law, to force them from their homes into the Indian Territory."[12]

White Eagle subsequently negotiated a settlement with the United States on behalf of the Ponca in January 1881 pursuant to which the Ponca agreed to remain in the Indian Territory for monetary reparation in the amount of $125,000 (2019: $3,609,847). His decision shocked political observers but his rationale was based on guaranteed national security in the Indian Territory from Sioux aggression in addition to unique economic opportunities in the Indian Territory such as leasing. On October 22, 1880, White Eagle symbolically declared his intention to remain in the Indian Territory by laying the cornerstone of a school on the Ponca Agency alongside Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce.[13] White Eagle deposited the Sioux scalp taken by his grandfather Chief Little Bear in a box at the laying of the cornerstone, symbolically closing a chapter of Ponca history.[13]

Following the enactment of the Dawes Act, however, White Eagle forged a close association with former Confederate general George W. Miller and leased most of the 110,000 acres which became the Miller 101 Ranch. In 1907, he later befriended oilman E.W. Marland. White Eagle became acquainted with Miller in then immediate aftermath of the Ponca Trail of Tears in July 1877 at the Quapaw Reservation as the Ponca waited disconsolately at Baxter Springs, homesick, and with considerable sickness. White Eagle and Miller soon developed a lifelong friendship built upon mutual respect as Miller learned the Ponca language. Miller quickly became a trusted advisor to White Eagle and the two held many conferences over the plight of the tribe. While inspecting land in the Cherokee Strip Col. Miller, Joe, and a number of cowboys found themselves near the proposed Ponca Reservation. After inspection Miller was satisfied that if White Eagle could visit the country he would accept the offer of the government and make it their home. Since White Eagle intended to leave soon for Washington to refuse the grant, Miller knew it was necessary to get word to him. Joe, his son, was the messenger. He was a mere boy but fully qualified to care for himself and since he knew and could speak the Ponca language he could meet and talk with them in their own way. He arrived just in time for White Eagle was preparing to leave for Washington. For the first time in the memory of the tribe, when the chiefs and head men met in council that night, a white boy sat in the center and answered their questions in their own tongue. It was decided that the next day White Eagle would return with Joe to view this land, and that the Poncas would never forget this kindness. The Indians moved to their new home in 1879.

The United States drastically altered its policies toward Native Americans Immediately following the Senate investigation of the Ponca removal by terminating the forced removal policy which began under President Jackson's Indian Removal Act.[3] White Eagle was later credited as being responsible for forcing this change in government policy.[14]

“We have been robbed of all we owned, but if we had thousands we would spend it all in bearing the expenses of the lawsuit carried on for us. We have nothing but our thanks to give.”

Opposition to the General Allotment Act of 1887 and the Oklahoma Land Run

.jpg.webp)

After successfully obtaining reparations for the unlawful removal, White Eagle remained a prominent advocate for Native American civil rights and the advancement of his people. He was one of the few outspoken opponents of the disastrous Dawes Act of 1887 which sought to culturally assimilate Native Americans into American society by withholding civil rights to Native Americans unless they agreed to abolish their governments, thereby relinquishing control of communal lands. In exchange, the United States would grant citizenship to individual Native Americans who agreed to accept small allotments of land. White Eagle accurately predicted to Senator Henry L. Dawes, for whom the Dawes Act was named, that it would “pluck the Indian like a bird” within three months.[15] Politically, the Dawes Act seriously eroded the role and authority of Native American governments; however, White Eagle fought to retain his power, telling American leaders that “a chieftainship is hard to break up.” (Hagan, 222). He strenuously objected to the surplus provision. He explained his refusal to comply: “when animals come out, there is grass for them to eat, and we would like to have land for the children when they come.”

When White Eagle's prediction turned out to be true, Dawes later described White Eagle as "the clearest head of all" Native American leaders on the issue.[16] President Hayes' Secretary of the Interior Carl Schurz regarded White Eagle as “one of the greatest men among the Indians.”[17]

White Eagle had used diplomacy and litigation to deflect the onrushing American immigrants, by 1889, these efforts had failed. This left the surviving Ponca facing reservation life and continuing pressures from the Harrison administration to acculturate. Federal officials demanded that the Ponca abandon their traditions and join the white American mainstream.

Following the Oklahoma Land Run of 1889, President Benjamin Harrison convened a commission with the objective of acquiring land occupied by thirteen separate Native American nations, including the Ponca, for the purpose of opening the land to American settlers. In 1891, White Eagle appeared before a panel convened by President Harrison who told him they needed more of his land due to the wave of new immigrants. He told them that "all the increase coming from over the big water [Atlantic Ocean] should stay on their own reservations.”

By 1892, Harrison's commission had successfully annexed land from every nation except the Ponca. On March 17, 1892, led by White Eagle, the Ponca were the first tribe to refuse to engage in negotiations. Commissioners attempted to acquaint the Ponca with the size of 80 acres by staking out two such plots and marking them with flags. To their disappointment, the Poncas declined all invitations to ride a wagon around the plots with White Eagle declaring that he already knew the size of 80 acres. (Hagan, 174). Commissioners told White Eagle that while the United States could not force them to sell their land, they would have no peace until they did. (Hagan, 171). During negotiations, Jerome attempted to persuade White Eagle suggested the white homesteaders "..stay on their own reservation." White Eagle felt there was no evidence that allotments, or lack thereof, made any difference in a tribe's standard of living. Over the course of 11 weeks, the commissioners schedule dozens of hearings and over the course of 11 weeks, the Ponca attendance declined, frustrating Jerome who threatened to get the Ponca to council, “if it takes the whole army.” (Hagan, 175).

On April 12, 1892, the Commission articulated President Harrison's proposal. Each Ponca would receive an allotment of 80 acres and $20, coming from the federal payment of $69,000.00 for the surplus lands. The balance of the purchase price would be placed in the United States Treasury where it would earn 5% interest, which would be paid annually at the rate of $10 per month to each tribal member. In the event the Ponca desired to withdraw the principle amount, each Ponca family of 5 would receive $1,000.00. Commissioners stated that if the Ponca accepted this offer, “they could live as they please,” and “could visit as much as they please, ” a remarkable statement considering the United States was attempting to discourage intra and inter-reservation visitation as prejudicial to the proper care of Native American property. (Hagan, 176).

White Eagle was highly critical of this offer. The depth of the Ponca resistance was immense and the Commission was unable to extract any concessions whatsoever.

A young Ponca testified that since the Ponca removed to the Indian Territory, the Ponca chiefs were “not the ones to say what we should do, the land belongs to all the men, women, and children and they have a right to say what shall be done with it.” (Hagan, 179). The Commission set out to use individualism to promote factionalism and set the Ponca against one another. (Hagan, 179). White Eagle continually asserted his authority and utilized his tactic of delay, saying he was not prepared to give any direction to his people on the issue until the federal plan was fully articulated. (Hagan, 179).

Leasing Ponca land to the 101 Ranch Wild West Show and Marland Oil

Though unsuccessful, White Eagle effectively utilized the Dawes Act by conveying Ponca land to a prominent oil tycoon when a large oilfield was discovered under the Ponca reserve in 1911. He forged a relationship with oil tycoon and future United States congressman E. W. Marland. He also leased significant acreage of the Ponca Reservation in the Indian Territory to the Miller Brothers 101 Ranch who used the land to establish what would become one of the most recognizable names in ranching and western entertainment, staging Wild West shows that provided employment for the Ponca people and entertained such personalities as King George V of the United Kingdom, President Theodore Roosevelt, and Will Rogers.

In September 1883, young Joe Miller, joined by Ponca Chief White Eagle, led a delegation of Poncas to the Alabama State Fair where he helped the Poncas establish an Indian village to hold traditional dances.

This included marching in parades on Mar. 18, 1899. In late 1902, White Eagle traveled to Birmingham, Alabama to perform in the 101 Ranch Wild West Show. In a sign of the times, White Eagle was forbidden to leave the Ponca Reservation without permission from the federal government:

Abdication and later life (1904-1914)

Abdication and inauguration of Horse Chief Eagle (1904)

White Eagle formally abdicated his position as hereditary chief on May 8, 1904, to his son and successor, Horse Chief Eagle, who would ultimately be recognized as the last hereditary chief in the United States[1] due to the enactment of the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act of 1936 prohibiting non-democratic Native American governments. White Eagle's abdication ceremony and the traditional buffalo hunt that followed was attended by an estimated 13,000 people.[18] The press described the ceremony as the last buffalo hunt in this history of the Great Plains.[18]

Death (1914)

White Eagle died on February 3, 1914, and is interred on Monument Hill in Noble County, Oklahoma.

Honors

Nieuw Amsterdam by Salvador Dali

In 1899, American sculptor and artist Charles Schreyvogel made a bronze statue bust of White Eagle. In 1974, the renowned Catalan-Spanish artist Salvador Dalí transformed the 1899 bust of White Eagle using via his Paranoiac-critical method.[19] Dalí transformed White Eagle's eyes into a scene depicting 17th century Dutch colonists seemingly celebrating Peter Minuit's 1621 acquisition of Manhattan Island from the indigenous owners for the proverbial string of beads by toasting bottles of Coca-Cola.[19] Dalí also transformed White Eagle's chin into a tabletop and his lips into a fruit basket.[19] British art historian Dawn Adès has argued that Dalí's work, known as Nieuw Amsterdam, symbolizes the foundations of American capitalism in the Dutch traders’ purchase of New York.[19] Nieuw Amsterdam is displayed at the Salvador Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida. The Dalí Museum describes White Eagle as "the celebrated chief of the Ponca tribe of Plains Indians, known for his vocal objection to the confinement of his people on reservations and his role in the subsequent ruling for equality for the Indian people in the 1870s."[19]

Other honors

- The White Eagle Oil & Refining Co. was formed in 1911 following the Supreme Court's breakup of Standard Oil into several geographically separate and eventually competing firms to break up a monopoly. By the time it was acquired by Mobil in 1930, White Eagle had gas stations in 11 states across the United States.

- The town of White Eagle, Oklahoma, is named in his honor and is the modern-day headquarters of the Ponca Nation of Oklahoma.

- White Eagle appears on the Ponca Code Talkers Medal issued by the United States Mint in 2013.[20]

Gallery

White Eagle in Arkansas City, Kansas on February 20, 1877

White Eagle in Arkansas City, Kansas on February 20, 1877 White Eagle in Washington, D.C. in November 1877

White Eagle in Washington, D.C. in November 1877 White Eagle in 1904 prior to his abdication

White Eagle in 1904 prior to his abdication.jpg.webp) White Eagle (R) and Standing Bear (L) as they appeared later in life (c.1890-1902)

White Eagle (R) and Standing Bear (L) as they appeared later in life (c.1890-1902) White Eagle's father Iron Whip in Washington, D.C. in March 1858

White Eagle's father Iron Whip in Washington, D.C. in March 1858.jpg.webp) White Eagle's son Horse Chief Eagle served as chief sovereign of the Ponca from 1904 until 1940.

White Eagle's son Horse Chief Eagle served as chief sovereign of the Ponca from 1904 until 1940.

See also

Footnotes

- Zimmerman, Charles Leroy (1941). White Eagle, Chief of the Poncas. Harrisburg, PA: Telegraph Press. p. 77.

- Coward, John M. (August 10, 1989). "Indians and Public Opinion in the Age of Reform: The Case of the Poncas" (PDF). ERIC. p. 2.

- Taylor, Quentin (Spring 2003). "President Hayes and the Poncas". The Chronicles of Oklahoma. LXXXI: 105. "Rutherford B. Hayes knew little about the forced relocation of the Indian tribes in the United States, but with new knowledge gained from the plight of the Poncas, Hayes ended the policy of removal before leaving office"

- Clark, Stanley (March 1943). "Ponca Publicity". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 29 (4): 495–516. doi:10.2307/1916600. JSTOR 1916600.

- "Chief White Eagle, 111, dies". The Daily Republican. February 6, 1914.

- Mackay, Charles (1859). Life and liberty in America: or, Sketches of a tour in the United States and Canada in 1857-8. pp. 94–96.

- Starita, Joe (2010). I Am a Man: Chief Standing Bear's Journey for Justice. St. Martin's Griffin; First edition. p. 63. ISBN 978-0312606381.

- Tibbles, Thomas Henry (1995). Standing Bear and the Ponca Chiefs. University of Nebraska Press. p. 119. ISBN 0803294263.

- Jackson, Helen Hunt (1881). A Century of Dishonor. Harper & Brothers. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-486-42698-3.

- Miami (Oklahoma) Daily News-Record, Mar. 1, 1957, p. 3.

- "The Aborigines". Chicago Daily Tribune. July 1, 1879. p. 12.

- Reports of Committees: 30th Congress, 1st Session - 48th Congress, 2nd Session, Volume 6, United States Congress. Senate, 1880, p. xix

- "BIG DOINGS AT PONCA AGENCY". Arkansas City Traveler. November 3, 1880. p. 1.

- "The Ponca Indians Have Lost Chief". The Altoona Tribune. March 19, 1914.

- Mathes, Valerie Sherer (1998). The Indian Reform Letters of Helen Hunt Jackson, 1879–1885. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-8061-5160-1.

- Hagan, William Thomas (2003). Taking Indian Lands: The Cherokee (Jerome) Commission, 1889-1893. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 173. ISBN 9780806135137.

- Chicago Tribune, Jan. 03, 1881, p. 7

- "Ponca Buffalo Hunt". The Washington Post. July 3, 1904. p. 6.

- "Nieuw Amsterdam (Bust of White Eagle)". The Dali Museum.

- "Ponca Tribe Code Talkers Bronze Medal". United States Mint.