Child nutrition in Australia

Nutrition is the intake of food, considered in relation to the body's dietary needs. Well-maintained nutrition includes a balanced diet as well as a regular exercise routine.[1] Nutrition is an essential aspect of everyday life as it aids in supporting mental as well as physical body functioning. The National Health and Medical Research Council determines the Dietary Guidelines within Australia and it requires children to consume an adequate amount of food from each of the five food groups, which includes fruit, vegetables, meat and poultry, whole grains as well as dairy products. Nutrition is especially important for developing children as it influences every aspect of their growth and development. Nutrition allows children to maintain a stable BMI, reduces the risks of developing obesity, anemia and diabetes as well as minimises child susceptibility to mineral and vitamin deficiencies.[1]

Dietary recommendations of a nutritional lifestyle

The nationally defined standard diet for the average Australian child between the ages of four through to eighteen is one that requires variety and consists of sustenance from all five of the food groups. The nationally available ‘healthy eating pyramid’ contains information about portioning as well as the type of food that should be consumed, to allow parents and children to adhere to a healthy and nutritional diet. Nutrition has its strongest and the most important impacts on a person during the early stages of life; this is in regards to organ, bone, muscle and body development.[2] The most common cause of poor development being an undernourished and inadequate diet, due to lack of dietary knowledge.[2]

It is suggested that children between the ages of 4-13 should be eating 4-5 serves (75g) of vegetables a day.[3] Vegetables are ‘nutrient dense’[3] and a good source of essential vitamins, antioxidants as well as fiber. 1-2 serves of fruit (150g) should also be consumed daily as it is essential in preventing early onset vitamin deficiencies. 1-2.5 serves of lean meats and poultry, such as fish, chicken, lamb, beef as well as legumes and nuts are also essential in a daily diet in order to maintain stable zinc and iron levels within a developing body. Whole grains should be consumed daily as they are high in fiber and low in saturated fats. Between 4-6 serves (40g) per day of rice, quinoa, rye, barley or pasta is critical to meet kilojoule requirements (8700kJ).[3] 2-3 servings (250ml) of dairy products such as, milk, probiotic yoghurt or cheese is also beneficial for stable muscle and bone development.[3]

It is common for children of the 21st century to indulge in consumer products that should be considered only as an occasional indulgence. Foods such as sweet biscuits, cakes, deserts, fast food as well as pastries and fruit juices are high in saturated fats as well as added sugars.[3] Saturated fats are responsible for raising blood cholesterol levels and in turn could put children at a much higher risk of contracting heart disease or inducing a heart attack. Thus five or fewer servings of sweet indulgences should be consumed in a week, as a maximum.[3]

Nutrition Australia ultimately seeks to help children "eat a rainbow"[3] by encouraging them to consume a fruit and a vegetable of a different colour every day to ensure that all beneficial properties of both fruit and vegetables are embraced. Educating children and exposing them to a healthier diet earlier on in childhood can achieve this.

The Australian Dietary Guidelines recommends children aged three to five years eat nutritious foods from each of the five food groups every day.

The following daily serves are recommended for children across this age group:[4]

| Recommended daily serves | Vegetables and legumes | Fruit | Grains | Lean meat, poultry, eggs, nuts, seeds and legumes | Milk, yoghurt, cheese and alternatives |

| Girls and boys two to three years | 2.5 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1.5 |

| Girls four to eight years | 4.5 | 1.5 | 4 | 1.5 | 1.5 |

| Boys four to eight years | 4.5 | 1.5 | 4 | 1.5 | 2 |

Exercise recommendations

Exercise is a fundamental feature of every growing child's life. Physical activity is essential for bone, muscle and body development in children as well as important for its role in burning excess calories and ensuring there are no lipid build-ups around significant organs such as the heart, liver, stomach or lungs.[5]

It is recommended that children between the ages of 5–18 years old participate in 60 minutes of moderate to rigorous exercise every day. [6] Such exercise could consist of planned sporting activities or just the frequent usage of a gym.

However the defined exercise standards are not being met, with a survey in 2012 revealing that only one in ten Australian children carried out the recommended 60 minutes of exercise a day.[7] A nationally conducted survey within Australia proved that in 2006, 974,000 children between the ages of 5-8 nationwide did not participate in a sport of any kind.[6] This is a staggering number, which is vastly contributing to the poor nutritional lifestyle that many Australian children are leading.

It is essential for children to enjoy the physical activities they are participating in, if the recommended standard of exercise is to be maintained. In 2009 Wellington public school in NSW underwent a study to increase nutrition and encourage increased physical activity among children. The study focused on 37 children spanning from the ages of 4 through to 13, of which their attitudes and daily exercise routine was reviewed. The study documented that there was initially a lapse in willingness to participate, however, after introducing fun games and engaging recreational sporting activities to the school culture, children began to engage more in physical activity. The outcomes being an overwhelming increase in whole school sporting participation.[8]

Physical activity among children has slowly been increasing, since the 2007 National Preventative Health Task force, released guidelines for healthy eating and physical activity routines for children.[7] The efforts of the NPHTF, as well as other nutritional organizations can be seen in the 52-58 (girls) and 66-69 (boys) percentage increase in organized sporting participation in 2009.[6] Organised nutritional programs are essential if Australians are to become more balanced in their dietary and lifestyle choices.

Australian consumer diet

Within Australia there is a broad spectrum of different diets that many children have adopted, as Australia is a country of many diverse cultures. However, without a doubt, there are trends reflecting a gross overconsumption of saturated fats and fast food being consumed habitually within Australia.

Fast food is consumed on a mass scale within Australia because it is convenient, cheap and widely available to the general public.[9] Currently in Australia, 360 Dominos stores exist and as of 2005, 869 McDonald's chains stand established in Australia.[10] Between 1987 and 2000, 2.77 meals ingested a week were from fast food franchises and in 2009 alone, an average of 127 dollars was spent weekly on fast food in Australia.[10] This rise in the consumption of pre-prepared meals is because fast food has become culturally accepted and is ideal for the busy everyday Australian lifestyle.

A 2014 report by Emily Brindal explored the prevalence and nutritional consequences of a diet based on fast food. She specifically focused on the purchasing behaviors of 523 Australians over the age of 16. The Report revealed that 27.3% of the Australians tested, consumed ready-made fast food once a week and a further 81.3%, admitted to consuming fast food within six months of the survey taking place.[9]

The food offered by franchises such as Hungry Jack's, McDonald's, Red Rooster and Dominos, which are among the most popular children's fast food venues,[9] provide limited nutritional value but a high caloric intake. A standard Hungry Jack Junior meal, which consists of a Whopper Junior, small chips and a medium Coke, contains 3147 kJ and 30.5 g of fat.[11] Other fast food options such as Sumo Salad, Grill’d burgers and Tex Mex are significantly healthier than their counterparts with a Beef Mini Me Pack burger, with water, containing 1730 kJ of energy, 18.7 g of fat and an added 22.4 g of protein.[12] As fast food is forming a larger part of the Australian diet, it is essential that Australian parents become more nutritionally aware and start encouraging the consumption of healthy take out options for their children, if any, to accommodate busy schedules.

The Results of Poor Nutrition

Obesity

"Obesity is an abnormal accumulation of body fat, usually 20% or more over an individual's ideal body weight".[13] "Obesity is a major contributor to the global burden of chronic disease and disability".[13] In 1995-2007 Australian children experienced a rapid 5-10% increase in child obesity and a further 23% of the child population in 2007 was considered overweight. [14] In 2015, 25% of Australian children were deemed to be either obese or overweight.[7] The 2% increase is substantial in relation to the whole population, whereby the weight gain can only continue to rise, if based on current Australian dietary trends. However, if adequate nutritional information becomes more extensively distributed and a wholesome lifestyle is adopted, the rise in obesity can be stopped.

A study conducted in 2013, further supported the proposed idea that a more widely distributed nutritional education, will act to reduce the rising levels of obesity within Australia. The study evaluated a sample of 59 pre school children throughout NSW and explored their attitudes towards exercise and obesity as well as their willingness to participate in child obesity preventative practices. Out of the study, 85% of the children expressed an interest in being involved in obesity prevention training. Thus by encouraging children to acknowledge the problem of obesity, Australians can significantly reduce the high levels of obesity that still currently exists in Australia. Furthermore, the study also documented the 2013 levels of obesity among pre schoolers in Australia as 20%, which was shown to have dropped by 3% since the 2007 recorded obesity statistic (23%), which links the increase in nutritional awareness and a decline in obesity.[15]

Several factors are contributing to a rise in obesity within Australia, with a large factor being advancing technology. In 2012 just over 44% of Australian children aged between 7-12 owned some sort of electronic gadget, that's primary location was in their bedroom.[16] A further 97% of children between the ages of 5-14 admitted to watching television for over 20 hours over the course of 2 weeks.[14] The increased emphasis placed on electronic media for entertainment is significantly cutting into time that could be spent interacting with friends or being involved in physical activity. Children could be encouraged to ride bikes or play team sports in order to meet the one-hour a day exercise requirements.

Children are impressionable and often adopt habits they observe their parents performing.[17] This means that it is essential for parents to demonstrate a healthy lifestyle in order to curb the national issue that is obesity. A 2013 study of 150 children, conducted in Germany revealed that the strongest influence on childhood obesity was the observation of parental obesity. Which caused children to adopt a lack of self-control and be less concerned with their thinness and prefer an enthusiastic feeding pattern to exercise.[18] This study can be applied globally to the average child's eating mentality as parents act as a child's first and primary role model in early life.

The national government is taking actions in order to reduce levels of obesity and has been since 2009. Whereby, The National Health and Medical Research Council used 39.2 million dollars of government grants to fund obesity research, with the major subsidy bodies being the National Heart and Diabetes Councils. Overall, the project acknowledged that prevention of obesity could only occur by encouraging an improved and nutritious start to life.[19]

Diseases

An inadequate diet provides an opportunity for several diseases to manifest within humans. This is due to the fact that a diet that does not adopt all five of the food groups can leave children malnourished and unable to develop at a steady or normal rate.

Anemia

Anemia is a medical condition that arises from a limited intake of iron, folic acid and B12 within a child's diet. A child between 12-14 is considered to have Anemia if they have less than 120g/L of hemoglobin in their blood. Around 3% of the average 12- to 17-year-olds in Australia are susceptible to this disease.[20] Anemia results in an inadequate production of red blood cells and hemoglobin or an increased destruction of red blood cells, which are necessary to transport oxygen to the body's cells. Oxygen provides the cells with the opportunity to perform aerobic respiration and ultimately contributes to stable energy levels within the body, necessary for the growth and development of the average child. [5] Children who do not consume red meat are at a higher risk of contracting anemia. Anemia can be managed through dietary and oral therapy whereby a higher elemental iron supplement of (30–60 mg) is recommended every day for children. Red blood cell transfusions may also be necessary for children with extremely low levels of hemoglobin in the blood.[20]

Diabetes

Diabetes type II is a progressive pancreatic condition that tends to be induced by lifestyle factors. "Obesity, lack of physical exercise and a poor diet are the major lifestyle factors that encourage this disease." Genetic predispositions also play a role, however, not as significant as environmental causes.[21] Diabetes among children, is on the rise within Australia, as revealed by a study in Western Australia in 2002. The study stated that 2 in every 100,000 children under the age of 18 in Australia were considered diabetic. The findings further suggested that Indigenous children were at a much higher risk, as 16 in every 100,000 children were considered to be diabetic.[22] The condition is one where the body cells are unable to absorb sufficient amounts of insulin, due to tissue resistance, thus being unable to reduce blood sugar levels after eating. The body requires insulin produced by the pancreas, in order to uptake glucose within the cells for the production of energy (ATP) and to perform active processes within the body, such as digestion, muscle contraction and brain stimulation.[22] Over time those susceptible will experience weight gain as well as nutritional gaps as they will be unable to adequately absorb nutrients required by the body. This is a fatal flaw in a developing child as it results in a failure to thrive and can potentially inhibit body development and cognitive functioning, due to cortical and muscular-skeletal atrophy.[23] Diabetes can be controlled by lifestyle changes such as increased exercise as well blood glucose level monitoring. However, no definitive cure exists.[5]

Calcium

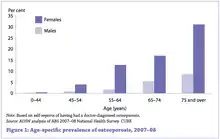

Calcium is a nutrient that can be gained through the consumption of primarily milk and cheeses, however, can also be derived from fish, as well as vegetables from the brassica family.[24] Children between the ages 4–8 should be consuming 1,000 mg/day of calcium to ensure adequate bone health.[25] Calcium's most essential function relates to the growth and strengthening of muscles and bones, with 1% of calcium also undergoing a crucial role in protein functioning.[5] A lack of calcium within the diet can ultimately lead to progressive bone diseases such as osteoporosis, which results in a loss of bone density due to the overactive osteoclasts reabsorbing bone matrix and overpowering the action of osteoblasts, which build calcium into the bone matrix.[25] Early onset calcium deficiency can result in children developing brittle bones, inhibiting their ability to participate in sporting activities and general weight bearing activities, without an increased risk of fracture and permanent bone damage.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D, also coined as the sunshine vitamin, is necessary within a child's diet as it allows body tissues and in particular bone to be properly nourished and mineralized. Vitamin D3, which is gained from dietary nutrients, is also essential for calcium absorption and homeostasis, which ensures standard muscle contraction and the transport of blood throughout the body.[26] Without adequate consumption of vitamin D, children can become predisposed to conditions such as rickets, which is the "softening or weakening of bones". [27] which can only be treated with vitamin D supplements, sunlight and surgery. Vitamin D is made available to children through exposure to sunlight as well as through food products such as egg yolks, fish, beef liver as well as fortified milk and margarine.[26] It necessary that the average 1-13-year-old child allows for 600 IU of Vitamin D a day. Children, who are dark skinned, vegans or are limited in their sun exposure, are more susceptible to this deficiency.[25]

Susceptibility in the Australian culture

Low socio economic groups are revealed to be more susceptible to poor nutritional patterns. This is due to lower levels of education and income, which is correlated with the inability to purchase nutritious whole foods or become more adequately educated on healthy dietary guidelines. Dr. Inglis, Dr. Ball and Dr. Crawford studied the influence of women in the household and concluded that "Women are primarily responsible for dietary choices"[28] Woman who are required to work full-time alongside their husbands in a relatively mediocre job, were shown to place a decreased emphasis on nutrition and an increased emphasis on convenience, due to the nature of their busy lifestyle. Whereas women who come from privileged backgrounds were able to dedicate more time to researching nutrition as well as have the monetary resources to afford foods such as lean organic meats and vegetables.[28] Such foods can be made into nourishing meals from scratch, without relying on pre-packaged foods for conveniences, providing a nutrient dense, low kilo joule intake. The lack of health consciousness among people of lower socioeconomic groups, thus stems from the higher costs of nutritious food in relation to inferior food options as well as for convenience.[28]

Furthermore, a 2013 Public Health and Nutritional Organisation study, explored the inferior nutrition standards of lower socioeconomic groups within Australia. The study selected random households throughout Melbourne Australia, in order to examine the correlation between financial conditions and the amount of fast food consumed within the Australian household. The study concluded that out of the 2500 households examined, 328 of the households who were also at the time experiencing financial difficulties, were more likely to purchase fast foods options rather than nutritional alternatives.[29] Thus to equalize the barrier between different socioeconomic groups, healthier food options should be made available at a more affordable price.

Indigenous Australians are a minority group that are also at risk of developing poor nutritional habits. The remoteness of rural indigenous populations and their reduced exposure to nutritional regulations has resulted in a 2013 study revealing that 30% of Indigenous Australians between the ages of 15-18 are considered obese and 8% of indigenous children between 2-14 are considered under weight or malnourished.[30] 2012-13 indigenous children between the ages of 2-14 were further surveyed and of this sample, 85% did not consume the recommended amounts of fruit or vegetables defined by the NHMRC. Poor dietary standards also extend to urban Indigenous Australians, as their diets are proven to include significant amounts of convenience foods, for reasons of lifestyle and affordability. The lack of health awareness is proven by the 97% of urban indigenous Australians who are unlikely to consume the recommended vegetable quota.[30] Exercise for many Indigenous Australians is a redeeming nutritional factor. A 2013 national study revealed that Indigenous children dedicate on average 6.6 hours to daily physical activity. This daily physical activity output is higher than the average Caucasian child.[14] However, for a nutritional lifestyle to be maintained dietary consumption must be in balance with physical activity.

References

- World Health Organization. "Nutrition, Pg 1". World Health Organization. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- Koletzko, B. (2008). Pediatric Nutrition In Practice, Nutritional needs and nutritional assessment (1st ed.).

- Australia Nutrition Foundation (2013). "Australian dietary guidelines".

- Woodward, Jodie (2020-01-20). "Food choices and child behaviour". Comprosition. Retrieved 2020-01-20.

- Marieb, EN.; Hoehn, KN. (2014). Pearson New International edition: Human Anatomy and Physiology (9th ed.). Harlow, USA: Pearson Education Limited.

- "Children's participation in cultural and leisure activities in Australia". Australian Bureau of statistics. 2009. Archived from the original on 2011-05-19.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2015). "Overweight and obesity by numbers".

- Fitzgerald, E.; Bunde-Birouste, A.; Webster, E. (2009). "Through the eyes of children: engaging primary school-aged children in creating supportive school environments for physical activity and nutrition. pg 127 – 132". Health Promotion Journal of Australia. 20 (2): 127–132. doi:10.1071/HE09127. PMID 19642961.

- Brindal, E.; Wilson, C.; Mohr, P.; Wittert, G. (2014). "Nutritional consequences of a fast food eating occasion are associated with choice of quick-service restaurant chain, 184–192". Nutrition & Dietetics. 71 (3): 184–192. doi:10.1111/1747-0080.12129.

- Lawrence, C. G. (2015). Influences on food and lifestyle choices for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians: An Aboriginal perspective (Ph.D. Thesis). University of Sydney. hdl:2123/12551.

- Hungry Jacks (2014). "Nutritional Guide, Whopper Junior Meal" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-02-02.

- Grill’d (2015). "Nutritional Guide, Mini Me Burger" (PDF).

- Medical Dictionary for the Dental Professions, Farlax. (2012). "Obesity definition. Pg 1-1".

- Australian Bureau Of Statistics. (2009). "Australian social trends".

- Denney-Wilson. E; Harris. M & Laws, R. & Robinson, A. (2013). "Child obesity prevention in primary health care: Investigating practice nurse roles, attitudes and current practices, 294–299". Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 49 (4): E294–E299. doi:10.1111/jpc.12164. PMID 23574563. S2CID 24674499.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Government Department of Health (2015). "Australians physical activity and sedentary guidelines;".

- Australian Government Department of Health. (2013). "Weighing it up: Obesity in Australia - Canberra: department of health;".

- Grube, M.; Bergmann, S.; Herfurth-Majstorovic, K.; Keitel, A.; Klein, A.M.; Klitzing, K.V.; Wendt, V. (2013). "Obese parents – obese children? Psychological-psychiatric risk factors of parental behavior and experience for the development of obesity in children aged 0–3. study protocol, 1471-2458". BMC Public Health. 13: 1193. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-1193. PMC 3878572. PMID 24341703.

- Wilson, E.D.; Campbell, K.; Hesketh, K. & Silva Sanigorski, A.D (2011). "Funding for child obesity prevention in Australia 184–192". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 35 (1): 85–86. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2010.00665.x. PMID 21299707.

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2013). "Australian health survey: Biomedical results for chronic diseases;".

- National Diabetes Services Scheme. (2015). "Type 2 diabetes; What happens with type 2 diabetes?".

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2014). "Type II diabetes in Australia's children and young people". Diabetes Series.

- Cranstron, I. (2012). "Diabetes and the brain". In N. Shaw; M. Kenneth; Michael H. Cummings (eds.). Diabetes: Chronic Complications (3rd ed.). NJ, USA: Wiley-Blackwell. p. 208. ISBN 978-0470656181.

- Arthur, R. (2007). "Calcium". Journal of Complementary Medicine. 6 (2): 46–54.

- Bhargava. H; Cassoobhoy. A; Nazario. B; Smith M (2015). "Vitamins and supplements lifestyle guide. Calcium;".

- Sahota, O. (2014). "Understanding vitamin D deficiency". Age and Ageing. 43 (5): 589–591. doi:10.1093/ageing/afu104. ISSN 0002-0729. PMC 4143492. PMID 25074537.

- Perlstein, D. (2015). "Rickets (Calcium, Phosphate, or Vitamin D Deficiency) Pg 1".

- Inglis, V.; Ball, K.; Crawford, D. (2005). "Why do women of low socioeconomic status have poorer dietary behaviours than women of higher socioeconomic status? A qualitative exploration Pg 334-343". Appetite. 45 (3): 334–343. doi:10.1016/j.appet.2005.05.003. hdl:10536/DRO/DU:30003101. PMID 16171900. S2CID 1895414.

- Burns, C.; Bentley, R.; Thornton. L., Kavanagh. A. (2013). "Associations between the purchase of healthy and fast foods and restrictions to food access: A cross-sectional study in Melbourne, Australia. Pg. 143-150". Public Health Nutrition. 18 (1): 143–150. doi:10.1017/S1368980013002796. PMID 24160171.

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2015). "The health and welfare of Australia's aboriginal and torres strait islander peoples; Determinants of health; socioeconomic and environmental factors pg 49-73" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-10.