Undernutrition in children

Undernutrition in children, occurs when children do not consume enough calories, protein, or micronutrients to maintain good health.[3][4] It is common globally and may result in both short and long term irreversible adverse health outcomes. Undernutrition is sometimes used synonymously with malnutrition, however, malnutrition could mean both undernutrition or overnutrition (causing childhood obesity). The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that malnutrition accounts for 54 percent of child mortality worldwide,[5] which is about 1 million children.[2] Another estimate, also by WHO, states that childhood underweight is the cause for about 35% of all deaths of children under the age of five worldwide.[6]

| Malnutrition in children | |

|---|---|

| |

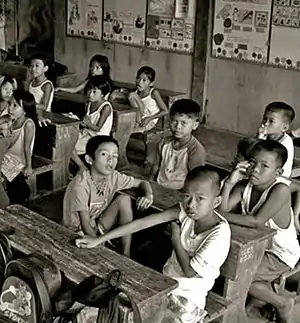

| Malnutrition due to soil transmitted helminth infections in school-age children in Guimaras Island, Philippines | |

| Symptoms | Stunted growth, underweight, wasting[1] |

| Deaths | 1 million a year[2] |

The main causes of malnutrition are often related to poverty: unsafe water, inadequate sanitation or insufficient hygiene, factors related to society, diseases, maternal factors, gender issues as well as other factors.

Background

Linked to 1⁄3 of all child deaths, malnutrition is especially dangerous for women and children. Malnourished women will usually have malnourished fetuses while they are pregnant, which can lead to physically and mentally stunted children, creating a cycle of malnutrition and underdevelopment. One of the most severe at risk populations are children under 5.[7] Malnutrition during the early stages of development can have negative and severe effects on growth and intellectual development. This effect on a child's intellectual quotient makes it harder for them later in life to achieve their true potential abilities. Breaking the cycle of malnutrition during early childhood development can break the cycle of intergenerational poverty among poor communities.[7]

There are a variety of ways in which malnutrition can affect the body. Globally, 162 million children show symptoms of malnutrition such as stunting, which is an indicator of malnourishment.[7] The WHO reported that two out of five children that are stunted live in Southern Asia, however Africa is the only region where there is an increasing number of stunted children.[8] Common micronutrient deficiencies are iron, zinc, iodine, and vitamin A. Micronutrient deficiencies can cause an increase of illness due to a compromised immune systems or abnormal physiology and development.[9]

Protein-Energy Malnutrition (PEM) is another form of malnutrition that affects children. PEM can appear as conditions called marasmus, kwashiorkor, and an intermediate state of marasmus-kwashiorkor. Although malnutrition can have severe and lasting health effects on women and children, they are still susceptible to other water-related dangers.[10]

Signs and symptoms

.jpg.webp)

Measures

There are three commonly used measures for detecting malnutrition in children:

- stunting (extremely low height for age),

- underweight (extremely low weight for age), and

- wasting (extremely low weight for height).[1]

These measures of malnutrition are interrelated, but studies for the World Bank found that only 9 percent of children exhibit stunting, underweight, and wasting.[1]

Children with severe acute malnutrition are very thin, but they often also have swollen hands and feet, making the internal problems more evident to health workers.[11]

Children with severe malnutrition are very susceptible to infection.[5]

Effects later in life

Undernutrition in children causes direct structural damage to the brain and impairs infant motor development and exploratory behavior.[12] Children who are undernourished before age two and gain weight quickly later in childhood and in adolescence are at high risk of chronic diseases related to nutrition.[12]

Studies have found a strong association between undernutrition and child mortality.[13] Once malnutrition is treated, adequate growth is an indication of health and recovery.[5] Even after recovering from severe malnutrition, children often remain stunted for the rest of their lives.[5]

Even mild degrees of malnutrition double the risk of mortality for respiratory and diarrheal disease mortality and malaria.[5] This risk is greatly increased in more severe cases of malnutrition.[5]

Undernourished girls tend to grow into short adults and are more likely to have small children.[12]

Prenatal malnutrition and early life growth patterns can alter metabolism and physiological patterns and have lifelong effects on the risk of cardiovascular disease.[12] Children who are undernourished are more likely to be short in adulthood, have lower educational achievement and economic status, and give birth to smaller infants.[12] Children often face malnutrition during the age of rapid development, which can have long-lasting impacts on health.[5]

Causes

Inadequate food intake, infections, psychosocial deprivation, the environment (lack of sanitation and hygiene), social inequality and perhaps genetics contribute to childhood malnutrition.[5]

Inadequate food intake

Inadequate food intake such as a lack of proteins can lead to Kwashiorkor, Marasmus and other forms of Protein–energy malnutrition.

Sanitation

The World Health Organization estimated in 2008 that globally, half of all cases of undernutrition in children under five were caused by unsafe water, inadequate sanitation, or insufficient hygiene.[6] This link is often due to repeated diarrhea and intestinal worm infections as a result of inadequate sanitation.[14] However, the relative contribution of diarrhea to undernutrition and, in turn, stunting remains controversial.[15]

Social inequality

In almost all countries, the poorest quintile of children has the highest rate of malnutrition.[1] However, inequalities in malnutrition between children of poor and rich families vary from country to country, with studies finding large gaps in Peru and very small gaps in Egypt.[1] In 2000, rates of child malnutrition were much higher in low- income countries (36 percent) compared to middle-income countries (12 percent) and the United States (1 percent).[1]

Studies in Bangladesh in 2009 found that the mother's illiteracy, low household income, higher number of siblings, less access to mass media, less supplementation of diets, unhygienic water and sanitation are associated with chronic and severe malnutrition in children.[16]

Diseases

Diarrhea and other infections can cause malnutrition through decreased nutrient absorption, decreased intake of food, increased metabolic requirements, and direct nutrient loss.[17] Parasite infections, in particular intestinal worm infections (helminthiasis), can also lead to malnutrition.[17] A leading cause of diarrhea and intestinal worm infections in children in developing countries is a lack of sanitation and hygiene. Other diseases that cause chronic intestinal inflammation may lead to malnutrition, such as some cases of untreated celiac disease and inflammatory bowel disease.[18][19][20]

Children with chronic diseases like HIV have a higher risk of malnutrition, since their bodies cannot absorb nutrients as well.[11] Diseases such as measles are a major cause of malnutrition in children; thus, immunizations present a way to relieve the burden.[11]

Maternal factors

The nutrition of children 5 years and younger depends strongly on the nutrition level of their mothers during pregnancy and breastfeeding.[21]

Infants born to young mothers who are not fully developed are found to have low birth weights.[22] The level of maternal nutrition during pregnancy can affect a newborn baby's body size and composition.[12] Iodine deficiency in mothers usually causes brain damage in their offspring, and some cases cause extreme physical and intellectual disability. This affects the children's ability to achieve their full potential. In 2011 UNICEF reported that 30 percent of households in the developing world were not consuming iodized salt, which accounted for 41 million infants and newborns in whom iodine deficiency could still be prevented.[23] Maternal body size is strongly associated with the size of newborn children.[12]

Short stature of the mother and poor maternal nutrition stores increase the risk of intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR).[12] However, environmental factors can weaken the effect of IUGR on cognitive performance.[12]

Gender

A study in Bangladesh in 2008 reported that rates of malnutrition were higher in female children than male children.[16] Other studies show that, at the national level, differences between undernutrition prevalence rates between young boys and girls are generally small.[24] Girls often have a lower nutritional status in South and Southeastern Asia compared to boys.[24] In other developing regions, the nutritional status of girls is slightly higher.[24]

Diagnosis

Measurements of a child's growth provide the key information for the presence of malnutrition. However, weight and height measurements alone can lead to failure to recognize kwashiorkor and an underestimation of the severity of malnutrition in children.[5]

Since undernourished children are also more likely to die from preventable infections, there is some research into developing a rapid diagnostic tool to detect malnourishment and common infections from a drop of blood. This research was spearheaded by Evelyn Gitau.[25][26]

Prevention

Measures have been taken to reduce child malnutrition. Studies for the World Bank found that, from 1970 to 2000, the number of malnourished children decreased by 20 percent in developing countries.[1] Iodine supplement trials in pregnant women have been shown to reduce offspring deaths during infancy and early childhood by 29 percent.[11] However, universal salt iodization has largely replaced this intervention.[11]

The Progresa program in Mexico combined conditional cash transfers with nutritional education and micronutrient-fortified food supplements; this resulted in a 10 percent reduction in the prevalence of stunting in children 12–36 months old.[13] Milk fortified with zinc and iron reduced the incidence of diarrhea by 18 percent in a study in India. In Nigeria, the use of imported Ready to Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) has been used to combat malnutrition in the North. However, research has shown that Soy Kunu, a locally sourced and prepared blend consisting of peanut, millet, and soya beans, contains the components of the Ready to Use Therapeutic Food (RUTF) and this has been used massively to reduce malnutrition in the north.[27]

Breastfeeding

Breastfeeding can reduce rates of malnutrition and dehydration caused by diarrhea, but mothers are sometimes wrongly advised not to breastfeed their children.[11] Breastfeeding has been shown to reduce mortality in infants and young children.[13] Since only 38 percent of children worldwide under 6 months are exclusively breastfed, education programs could have large impacts on children's malnutrition rates.[28] However, breastfeeding cannot fully prevent PEM if not enough nutrients are consumed.[5]

Treatment

.jpg.webp)

Treatment with antibiotics such as amoxicillin or cefdinir improves the response and survival rate of severely malnourished children to an outpatient treatment plan which provided therapeutic food.[2] This confirms the recommendation, "In addition to the provision of RUTF [ready-to-use therapeutic food], children need to receive a short course of basic oral medication to treat infections." contained in "Community-based management of severe acute malnutrition, A Joint Statement by the World Health Organization, the World Food Programme, the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition and the United Nations Children's Fund."[29]

Epidemiology

The World Health Organization estimates that malnutrition accounts for 54 percent of child mortality worldwide,[5] about 1 million children.[2] Another estimate also by WHO states that childhood underweight is the cause for about 35% of all deaths of children under the age of five years worldwide.[6]

According to a 2008 review, an estimated 178 million children under age 5 are stunted, most of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa.[13] A 2008 review of malnutrition found that about 55 million children are wasted, including 19 million who have severe wasting or severe acute malnutrition.[13] In 2020, a research paper that mapped stunting, wasting, and underweight among children across 105 low- and middle-income countries found that only five countries were expected to meet global nutrition targets in all second administrative subdivisions.[30]

As underweight children are more vulnerable to almost all infectious diseases, the indirect disease burden of malnutrition is estimated to be an order of magnitude higher than the disease burden of the direct effects of malnutrition.[6] The combination of direct and indirect deaths from malnutrition caused by unsafe water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) practices is estimated to lead to 860,000 deaths per year in children under five years of age.[6]

See also

References

- Adam Wagstaff; Naoke Watanabe (November 1999). "Socioeconomic Inequalities in Child Malnutrition in the Developing World". SSRN 632505.

- Trehan, Indi; Goldbach, Hayley S.; LaGrone, Lacey N.; Meuli, Guthrie J.; Wang, Richard J.; Maleta, Kenneth M.; Manary, Mark J. (2013-01-31). "Antibiotics as part of the management of severe acute malnutrition". The New England Journal of Medicine. 368 (5): 425–435. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1202851. ISSN 1533-4406. PMC 3654668. PMID 23363496.

The addition of antibiotics to therapeutic regimens for uncomplicated severe acute malnutrition was associated with a significant improvement in recovery and mortality rates.

- Young, E.M. (2012). Food and development. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. pp. 36–38. ISBN 9781135999414.

- Essentials of International Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2011. p. 194. ISBN 9781449667719.

- Duggan, Christopher; Watkins, John B.; Walker, W. Allan (2008). Nutrition in pediatrics: basic science, clinical applications (4th ed.). Hamilton, Ontario: B.C. Decker. pp. 127–141. ISBN 978-1-55009-361-2. OCLC 492175371.

- Prüss-Üstün, A., Bos, R., Gore, F., Bartram, J. (2008). Safer water, better health – Costs, benefits and sustainability of interventions to protect and promote health. World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland

- Mabhaudhi, Tafadzwanashe; Chibarabada, Tendai; Modi, Albert (2016). "Water-Food-Nutrition-Health Nexus: Linking Water to Improving Food, Nutrition and Health in Sub-Saharan Africa". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 13 (1): 107. doi:10.3390/ijerph13010107. PMC 4730498. PMID 26751464.

- "Levels and trends in child malnutrition: UNICEF/WHO/The World Bank Group joint child malnutrition estimates: key findings of the 2019 edition". World Health Organization. Retrieved 2022-12-09.

- Black, R. (2003) Micronutrient Deficiency – An Underlying Cause of Morbidity and Mortality. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 81(2). 79. https://www.scielosp.org/pdf/bwho/2003.v81n2/79-79/en

- Atassi, H. (2019). Protein-Energy Malnutrition. MedScape. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1104623-overview

- "Facts for Life" (PDF). UNICEF. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Victora, Cesar G; Adair, Linda; Fall, Caroline; Hallal, Pedro C; Martorell, Reynaldo; Richter, Linda; Sachdev, Harshpal Singh; et al. (Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group) (2008-01-26). "Maternal and child undernutrition: consequences for adult health and human capital". Lancet. 371 (9609): 340–357. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61692-4. ISSN 0140-6736. PMC 2258311. PMID 18206223.

- Bhutta, Z. A.; Ahmed, T.; Black, R. E.; Cousens, S.; Dewey, K.; Giugliani, E.; Haider, B. A.; Kirkwood, B.; Morris, S. S.; Sachdev, H. P. S.; Shekar, M.; Maternal Child Undernutrition Study Group (2008). "What works? Interventions for maternal and child undernutrition and survival". The Lancet. 371 (9610): 417–440. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61693-6. PMID 18206226. S2CID 18345055.

- World Bank (2008). Environmental health and child survival epidemiology, economics, experiences. Washington, DC: Environment Department of the World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-7237-1.

- Ngure, Francis M.; Reid, Brianna M.; Humphrey, Jean H.; Mbuya, Mduduzi N.; Pelto, Gretel; Stoltzfus, Rebecca J. (January 2014). "Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH), environmental enteropathy, nutrition, and early child development: making the links". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1308 (1): 118–128. Bibcode:2014NYASA1308..118N. doi:10.1111/nyas.12330. PMID 24571214. S2CID 21280033.

- Khan, MM; Kraemer, A (August 2009). "Factors associated with being underweight, overweight and obese among ever-married non-pregnant urban women in Bangladesh". Singapore Medical Journal. 50 (8): 804–13. PMID 19710981.

- Musaiger, Abdulrahman O.; Hassan, Abdelmonem S.; Obeid, Omar (August 2011). "The Paradox of Nutrition-Related Diseases in the Arab Countries: The Need for Action". International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 8 (9): 3637–3671. doi:10.3390/ijerph8093637. PMC 3194109. PMID 22016708.

- NHS (4 December 2016). "Complications of coeliac disease".

- Altomare R, Damiano G, Abruzzo A, Palumbo VD, Tomasello G, Buscemi S, et al. (2015). "Enteral nutrition support to treat malnutrition in inflammatory bowel disease". Nutrients (Review). 7 (4): 2125–33. doi:10.3390/nu7042125. PMC 4425135. PMID 25816159.

- Newnham, E. D. (2017). Newnham (ed.). "Coeliac disease in the 21st century: paradigm shifts in the modern age". J Gastroenterol Hepatol (Review). 32 Suppl 1: 82–85. doi:10.1111/jgh.13704. PMID 28244672.

The epidemiology of coeliac disease (CD) is changing. Presentation of CD with malabsorptive symptoms or malnutrition is now the exception rather than the rule.

- Sue Horton; Harold Alderman, Juan A. Rivera (2008). "The Challenge of Hunger and Malnutrition" (PDF). Copenhagen Consensus Challenge Paper. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 15, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Dewan, Manju (2008). "Malnutrition in Women" (PDF). Stud. Home Comm. Sci. 2 (1): 7–10. doi:10.1080/09737189.2008.11885247. S2CID 39557892. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- "Micronutrients – Iodine, Iron and Vitamin A". UNICEF. 14 December 2011. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- Nubé, M.; Van Den Boom, G. J. M. (2003). "Gender and adult undernutrition in developing countries". Annals of Human Biology. 30 (5): 520–537. doi:10.1080/0301446031000119601. PMID 12959894. S2CID 25229403.

- Staff, Quartz (7 July 2016). "Quartz Africa Innovators 2016 list". Quartz Africa. Retrieved 2020-08-17.

- The Associated Press (2016-03-11). "Africa's Next Einstein Forum builds expertise in science, tech, engineering, math".

- Chinedu, Obasi (October 12, 2018). "Severe Malnutrition, A Disturbance in Nigerian Health Sector". Public Health Nigeria.

- UNICEF. "Introduction to Nutrition". UNICEF. Retrieved March 3, 2014.

- World Health Organization; The World Food Programme, the United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition and the United Nations Children's Fund (May 2007). "Community-based management of severe acute malnutrition" (PDF) (in English and French). World Health Organization. Retrieved January 31, 2013.

- Kinyoki, Damaris K.; Osgood-Zimmerman, Aaron E.; Pickering, Brandon V.; Schaeffer, Lauren E.; et al. (Local Burden of Disease Child Growth Failure Collaborators) (January 8, 2020). "Mapping child growth failure across low- and middle-income countries". Nature. 577 (7789): 231–234. Bibcode:2020Natur.577..231L. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1878-8. ISSN 0028-0836. PMC 7015855. PMID 31915393.

Further reading

- Roger Thurow (2016). The First 1,000 Days: A Crucial Time for Mothers and Children—And the World. PublicAffairs. ISBN 978-1610395854.